Fixing Online Gaming Idiocy: A Psychological Approach

In this in-depth article, Fulton discusses why "the online behavior of [gamers] is dramatically reducing our sales", referencing his social design on titles such as Microsoft's Shadowrun to explain how we can dissuade anonymous Internet idiots.

[In this in-depth article, Fulton discusses why "the online behavior of our customers is dramatically reducing our sales", referencing his social design on Microsoft's Shadowrun to explain how we can dissuade anonymous Internet gamers.

Warning: This article uses language inappropriate for a professional website. Unfortunately, the language used is far less offensive than what is commonly encountered in online gaming.]

Some gamers are fuckwads

Of all the ways I spend my free time, playing games online is the only one I would describe as "frequently barbaric". Insults of all kinds, including racist and homophobic slurs, are commonplace.

The women I know who play online avoid anything that would identify them as female -- including voice communication -- in order to avoid the unwanted, and frequently negative, attention.

And that's just how players are intentionally insulting -- what some people do while playing online can also be aggravating.

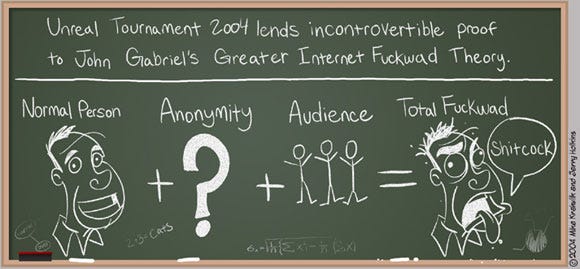

Cheating, team-killing, entering a game but not playing, quitting before the game is over, and more, are all relatively common. Common enough that it was deemed worthy of a Penny Arcade comic, speculating about why normal people become fuckwads online.

Image courtesy of Penny Arcade

So what?

Why do I care? Some gamers might be thinking "If he's so thin-skinned that he can't take the online banter, maybe he shouldn’t play online." Unfortunately, many people do just that -- they stop playing online.

Even more gamers go online a few times and then never play again. This isn't just my personal speculation; I have seen convincing data from two different sources that the biggest problem with online gaming is the behavior of others. The biggest problem isn't the cost; it isn't connectivity issues, or even the quality of the games -- it is how people are fuckwads online.

To make this concrete, here's a thought experiment for you: imagine you go to a new restaurant, and decide to try the meatloaf. A big guy at the next table overhears you, looks at you, and yells: "Meatloaf? What kinda newb are you? Hey everybody, this r-tard just ordered the meatloaf!

God, I'm glad you're not at my table." Laughter breaks out at the tables around you, as they crane their heads to look at the newb. The restaurant staff is nowhere to be found, and you're not entirely certain they'd do anything anyway -- you can tell this is normal behavior at this place. How good or cheap would the food have to be to get you to go back there? Who would you bring there? The vast majority of the world population wouldn't go back there, and would warn everyone they knew to avoid it.

So again, why do I care? Because the online behavior of our customers is dramatically reducing our sales, and continues to stunt the growth of our industry. Non-gamers simply don’t love games enough to put up with the crap they get online. The reason they would consider playing online is to have fun with other people -- and right now, playing games online with strangers rarely delivers that for anyone outside the hardcore demographic.

Are these problems even solvable?

Short answer: yes. Social environments and culture can be designed. Just like good game design creates fun gameplay, good social design creates fun social experiences. Unfortunately, online games seem to have allocated very few resources to designing the social environment.

But honestly, I don't believe that resource constraints are the source of the problem -- I think that most people don’t believe that social problems can be solved. A common belief that I’ve heard used as justification for not addressing the social environment of games is that "jerks will be jerks". Essentially, many people believe that:

1. Behavior is determined by personality, and

2. You can’t change people’s personality

While I (mostly) agree with the second point, it is moot because the first point has been consistently contradicted by 60 years of social psychological research. Human behavior is complex and determined by many factors.

Personality is certainly one factor, but it is a surprisingly small factor. The largest determinant of behavior is the perceived social environment. This is the good news, because both the social environment and the perception of it can be controlled.

But me just saying that I disagree with a belief isn’t an argument; some proof is in order. Evidence about the effect of the social environment on behavior comes from two main sources: real-world observation and academic studies from social psychology.

(Although perhaps I should add "cartoonists" to those two sources. The Penny Arcade comic showing a normal person becoming a total fuckwad when in multiplayer gaming situation -- anonymous, with an audience -- was pretty accurate, if a bit simplified.)

Evidence of how the social environment affects behavior

In real life, people are capable of an incredibly wide variety of behaviors. People go to a bar on Saturday night and church on Sunday morning and manage not to get kicked out of either. How? They don't sing hymns and pray while at the bar, and don't smoke and drink during the sermon.

In academia, social psychologists have demonstrated how far they can push human behavior by controlling the perceived situation. One of my favorite studies was done in 1973 by Darley & Batson about "bystander intervention". They wanted to determine the effect that the situation had on the likelihood that people would help a stranger in need.

In their experiment, they told Princeton seminary students that they had to go to the building next door to record a sermon. Some of them were told that they were late, and should hurry next door. Others were told they were early, but should go next door and wait there. While moving between buildings each person had to walk by a man who slumped in a doorway, coughing and moaning.

Of the ones who were told to hurry, 10% stopped to help the man in distress. On the other hand, 63% of the ones who felt they had plenty of time stopped to help the man. Some of them literally stepped over the distressed man while rehearsing the sermon to themselves!

The topic of the sermon? The parable of the Good Samaritan, of course. (Who says psychologists have no sense of humor?)

Examples of successful social design in real life

Psychological experiments are interesting, but they have no value if they don't lead to influencing social behavior in real life. In part, the situation affects us so often and so much that most people don't even notice good social design. For example, one brilliant piece of social design comes from the first psychologists: bartenders.

Telling bar patrons that they can't have more alcohol because it is closing time can be an ugly situation. Their solution: many bar tenders give first call about an hour before they close and second call about 15-20 minutes before they close.

This advance warning before last call minimizes the potentially socially difficult (and even dangerous) situation of surprising drunk people with the news that the party is over. Bartenders could do many other things -- call the cops, refuse to serve the annoying patron in the future, etc., but they risk losing the customer if they go to those extremes.

A more relevant example is how the movie industry changed the culture of moviegoers in response to the threat of cell phones. Prior to the popularization of cell phones, people had one main behavioral response to a ringing phone: answer it.

When cell phones were introduced, some people applied their "just answer it" behavioral response everywhere they went... including movie theaters. During the movie. After all -- what were they supposed to do? Not answer?

The theater industry initially ignored this threat to the social experience of going to the movies, but in the past few years has aggressively begun running "silence your cell phones" ads immediately before the show.

My personal experience is that that cell phones don't ring nearly as much during movies now as they did 10 years ago. And people actually talking on them during moves is (thankfully) rare. The theater industry recognized that their unique value (over watching movies at home) is the social experience, and moved to silence that threat (sorry -- couldn’t resist). The health of their industry depended upon their changing the rules of acceptable social behavior in theaters.

I'm not citing this example to say that games should run ads before going online saying "don't be a jerk" -- that would be naïve in the extreme. The point of that example is that the movie industry recognized that some of its patrons were pissing off the majority of their other patrons.

And so they (eventually) took effective steps to reduce it. The belief that "jerks will be jerks" is neither true nor useful -- it is a belief that permits us to wash our hands of our ability to gain a wider audience. It isn't a responsibility for us any more than it was for the movie industry -- but the economic incentives are the same.

Examples of useful social design in games

Most multiplayer games and platforms already have some successful social features. Friends lists, guilds/clans, and party systems are all examples of useful social design. I think everyone can agree that those social features definitely increase the fun of playing multiplayer.

But those features are not enough; they are really only valuable if you already have friends online. If the multiplayer games are going to be welcoming to new players, we need social features that affect newbie who may not (yet) have friends.

A useful feature that doesn't require friends is the swear words filter for text chat. Even well-moderated text chat channels get nasty. But when the swear word filter changes words deemed "offensive" ("asshole!") into something less offensive ("*%@^!"), the reaction to the swearing drops dramatically, because this change makes the swearer look... well, silly.

Amusing, like a cartoon character, rather than aggravating. I'll bet some newbs don’t even realize that the swear word filter exists until they type some choice words themselves and see their own chat "sanitized".

Another example of social design comes from Shadowrun, a team-based multiplayer shooter I worked on. One of the fundamental problems of team-based games is that some players (especially shooter players) aren't naturally team-oriented.

It is fairly common for team members to focus on beating teammates for prestige (high score, kills, scores, etc.) rather beating the enemy. Pre-pubescent voices often scream "kill stealer!" at a teammate during a team deathmatch, because they are focused more on their personal stats rather than winning as a team.

In order to reduce this kind of anti-team behavior, we changed the stats system to reward pro-team behavior over individual success.

We made the rewards for killing enemies proportional; so if one player does 90% of the damage and a teammate steals the kill, the first player gets 90% of the credit (and money!) for the kill, and the stealer gets 10%.

On several occasions, I heard players new to Shadowrun complain about teammates stealing their kill stealing, only to have team members tell the new player something to the effect of "that's not how this game works".

Multiplayer shooters often have "vote-kick" systems that allow the majority of players to kick an annoying player out of the game. While a good idea in principle, more often than not, the vote-kick system itself becomes a social annoyance rather than social boon.

Griefers often call votes to kick innocent people out of the game; or two players will get into a feud and will repeatedly call votes to kick the other player out. Often, no one is kicked because many people choose not to vote -- they don’t want to be judges, they just want to play.

Another example from Shadowrun is how we empowered the players in a game to protect themselves against griefers. Shadowrun's solution to these two social problems with vote-kick systems was to decrease vote calling in all but the most serious of situations (i.e., when the majority of players are likely to vote to kick). Two specific changes we made to the typical vote-kick system:

We made calling a vote a risky behavior. Typically, voters have two choices: abstain or kick the target of the vote. The wrinkle we added was to give voters a third choice: kick the vote caller. This change meant that if a griefer called a random vote, there was a chance they themselves could end up out of the game.

We stopped feuds at the second vote. We changed the typical vote-kick system to understand the concept of a feud. After one player calls a vote on another player, the server considers the pair to be in a "feud" state.

If either of the feuding pair calls a vote against the other, the vote is handled differently than with non-feuding pairs -- instead of the possibility that neither feuder gets kicked, a vote between a feuding pair always results in one player getting kicked. This change meant that players learned to not to call a vote in a feud -- unless they're willing to leave the game session rather than continue playing with the other person.

These two changes to the typical vote-kick system resulted in a dramatically better social environment -- a majority of players could still get rid of annoying players, but griefers couldn't simply pervert the vote-kick system to become another means for griefing.

Furthermore, if two players got into a feud, the feud would end quickly (at the second vote), thus sparing the other players from having to tolerate the toxic environment of two players who are more intent on personal attacks than playing the game. Once bad blood happens, it's just best to separate the parties.

I gave these examples of social design -- of feature designed to enhance the social fun of playing multiplayer -- in order to point out that multiplayer gaming already has some social features and social design (not that they call it that).

But much more investment in social design is needed. Most of the features are targeted towards hardcore gamers and not toward creating a community that is welcoming to new players.

The games and gaming platforms that create satisfying social environments for non-hardcore players will reap the rewards of a larger and more loyal customer base. Again, much of the enviable success of WoW is attributable to Blizzard's ability to create a social environment that is friendly to newbs while catering to the hardcore. They've shown it is possible to do both.

Conclusion

You don't have to let fuckwadism hurt your multiplayer game’s popularity or sales. Social environments can be designed to minimize bad behavior. Social conflict is inevitable in online gaming -- but it doesn't have to be as frequent or severe as it is.

But if you don’t design the social environment, your game will probably end up feeling like most do right now -- like the lawless territories of the Wild West.

Despite our romantic imagery, it was the desperate, the poor, the misfits and criminals who went west; the majority of the people stayed back east where there were paved roads, doctors, nice restaurants and little chance of getting gunned down in what passes for a street. If we want multiplayer gaming to grow, we have to start designing the social environment(s) to appeal to people other than trash-talking, hardcore gamer.

Gaming is finally starting to broaden -- The Sims, WoW, the Wii, Harmonix, casual games, and more are introducing gaming to new kinds of people. But how many of those newbie gamers will be mocked instead of welcomed to their first multiplayer game? In your multiplayer game? Without careful social design, the answer is "almost all of them".

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)