Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Former Edge EIC and current development director of social game developer Hide&Seek Margaret Robertson begins a column in which she picks five minutes of play within a game -- here the meat of Geometry Wars 2's Deadline mode -- and finds out precisely what makes it tick.

[Former Edge EIC, acclaimed GDC speaker and current development director of social game/'playful experience' creator Hide&Seek Margaret Robertson begins a new column for Gamasutra in which she picks five minutes of play within a game -- here the meat of Geometry Wars 2's Deadline mode -- and finds out precisely what makes it tick.]

Here's something that someone in our industry, somewhere, says every day: "journalists ought to finish the game they review". It was Vince Zampella most recently, at QuakeCon, airing his very reasonable frustration at poorly-informed reviews, if perhaps not his ability to run on-the-spot mental arithmetic of what a 50 hour workload does to the average freelance review rate.

Here's something that no one in our industry ever says, anywhere: "I get all the time I need to finish all the games I want."

Literally everyone I know in gaming has a stack of boxes next to the TV -- probably a couple still in their cellophane -- taunting them for their lack of spare time.

Everyone I know goes through the five-stage cycle of game acquisition (anticipation, excitement, frustration, denial, guilt) as the release date finally arrives, the first thrilling afternoon is invested, the next dozen evenings fly by in a flurry of family and work commitments, and the perky pretense that you'll go back to it one day is gradually replaced by a glumly solid certainty that you won't.

And, as the game industry gets bigger and faster, more varied and more interesting, the cycle accelerates. I caught myself trying to form a coherent opinion on The Incident the other day, after around 38 seconds of play. I stopped myself and perkily promised that I'll go back to it, but... Well, you know how that one ends already.

But for all of us, whether we're being paid to or not, the pressure that we put ourselves under when we talk about games is immense. We take these mammoth, complex, changeable creatures and expect to be able to offer a definitive assessment. Is it any good? we ask our reviewers, our friends, ourselves. Is it better than the original? Is it worth $60? Did the publisher rush it out?

Damned if I know. Games are huge. Even little games are huge. There is great skill and valuable purpose in condensing a critical assessment into a thousand words, but it's an inherently artificial and incomplete way of exploring what that game consists of.

Now that I spend my days designing, rather than analyzing, I'm more and more aware of the millions of tiny decisions that make up each game, of the barely detectable intricacies which produce the general impression.

Because of that, I wanted this new series of columns to be about the finest, most granular detail of games. I didn't want to add to the slew of writing that tries to form overall value judgments. And -- much as I love it -- I also didn't want to add to the rapidly evolving tradition of experiential game-writing.

I wanted to dig as deep as I could as efficiently as I could, not in the effort to produce a summation of the game, but to air things within it that were interesting. So not, "is it good", but "what's in it that's good?" Or bad, of course. Or massively dumb or brilliantly silly. I want to see detail that you'd never see looking at the whole, and get time to talk about the things that normally get dismissed in a caption or an aside.

So, welcome to "Five minutes with..." The idea is to take five different minutes of a different game each time, and suck them dry.

Sometimes it might be the first five minutes. Sometimes the last. Sometimes one iconic scene, sometimes something boringly representative, sometimes something wildly uncharacteristic. All that they'll have in common is that interesting things lie within.

Except -- double dammit -- I'm now a third of my way through my column which, when you've only got five minutes to play with, puts you in a pickle. Unless, of course, you've had the foresight to pick a game with a name only an ex-journalist could love, and a truncated timeframe to match: Geometry Wars Retro Evolved 2's Deadline mode.

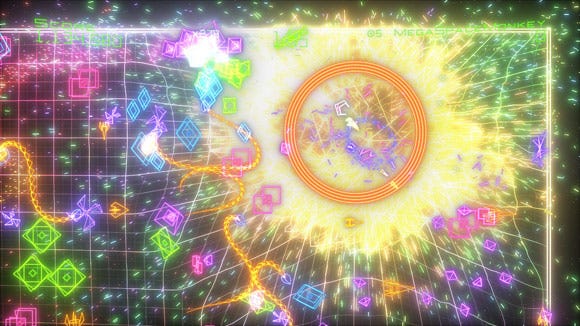

Three minutes, infinitive lives -- Deadline is pure score attack. If you've not played it, it's one of the quickest modes in twin-stick classic GW2 to get dazzlingly, garishly manic, escalating enemy variety and density faster than Evolved or even Waves. I may be almost exactly 100 times less good at it than this chap, but even my games seethe and squirm with fizzing neon.

In principle, the pressure ought to be off, since you've got a infinitive lives and a stock of smart-bombs. In practice, the game quickly becomes so pulsingly busy that I not infrequently become blind to the position of my own ship.

I'm still playing - still winning - but have no visual awareness of the bright white claw I'm actually steering. The bit of my brain that handles moving knows where it is, but the bit of my brain that does the thinking has no idea, and they very rapidly start screaming at each other.

I'm not sure I could take much more than three minutes of that kind of psychosis, which is handy because that's exactly how long Deadline lasts. Never longer, never shorter. One of the smartest, quietest design decisions in GW2 is the non-inclusion of a restart option.

There are only a couple of modes you can meaningfully cock up without dying -- Deadline and Sequence, notably -- but catering to the rage-quit instinct would interrupt the rhythm that the game maintains from the second it loads.

Few games handle failing and replaying with quite such instantaneous precision, and walking away from the notional three-minute challenge of Deadline in less than precisely 27 or 54 or 93 minutes is a rare triumph of will-power.

It's enough to drain a wireless controller, and I couldn't recommend doing so more highly. Plug yourself back in, pull a chair up to the screen and press your nose as close as you dare. Your scores will suffer, since this is a game where eyeball travel time has a significant performance impact, but you'll see such wonders. Even from a distance, it's a game that I'd risk saying has a timeless beauty.

It's hard to believe that it will ever look anything other than perfectly realized. The style may fall out of fashion, but the quality of execution won't. Close up, however, my respect for it increased even further.

It's not your increasingly tortured imagination which makes you think the shapes have some kind of implacable viral intelligence behind them, as they relentlessly pursue your death: it's the animation. The Ducks and Grunts and Weavers all play subtle little morphing tricks, refusing to resolve into 2D patterns or 3D shapes.

Their little tricks of acceleration and hesitation don't just add difficulty, they add life. It's part of what makes going back to the first game feel a little flat.

That, and the changes to the scoring system. It's easy to forget how radical the design shifts between first and second were. A quick glance suggests a glossier upgrade of an identical game, but the reality is new enemies, new modes, different weapons system and the arrival of "geoms", the fragments left by downed enemies which act as multiplier pick-ups.

I'd never stopped to look at how much they changed my game before, but the need to sweep back over territory previously cleared has a radical impact on how you play. It adds a whole new tactical consideration, of course, but also an extra dimension of tactility to the play.

The game has always caused you to endlessly orbit and quarter the screen, but now after you slice across it, breathing death as you go, you find the need to circle back in a victory lap. First you burn the threat away, then you stroke your ship across the mess that's left behind. It's not quite as cathartic as Super Mario Sunshine's gunk-cleaning, but it's a visceral connection all the same.

And Deadline, of all the modes, makes you most conscious of the clever things that GW2 does with color and mess. When death comes -- and it will -- it comes in a vast gush of white sparks. The music swallows itself and the screen clears. In an instant, a screen that was thick with jelly-bean brightness becomes starkly, calmly monochrome.

White ship, black sky. It's a beautifully orchestrated moment of punctuation -- a punishment and a respite all at once. it's a trick games use all too rarely -- Bit.Trip Beat does it simply, but beautifully. In Deadline, however, something subtler starts to emerge.

When you start playing, dying is something of a relief. It's happened because you've become overwhelmed with enemies. Dying clears the screen, and you get to continue with a bit more breathing space -- at least for a while.

But as you start to thirst for higher scores, that black, empty screen becomes the biggest enemy you face. With only three minutes to harvest all the points you can, any moment when it isn't thick with cannon fodder is a moment your chances are slipping away. You come to dread black screen, to flee it in the search of enemies, which you've now come to see as a resource rather than just a threat.

The concept of the reversal, of course, is one familiar to anyone who's taken an interest in scriptwriting 101, but it's interesting to see it constructed in gameplay terms, rather than narrative. Ikaruga is the master here, of course, as black and white bullets flick endlessly between friend and foe.

We tried a take on it recently, in a puzzle game for Channel 4, about weak links and heavy beads. Building game systems where opportunity and threat are embodied in the same object is incredibly satisfying, but arduous, since there's no fat to trim when you lose the balance.

But balance isn't something Deadline struggles with. There are so many small details that could have ruined it. Enemy speed millimetrically faster. Smart bombs replenished a little more rarely. Imagine how catastrophically annoying it would be if the walls killed you. It hits none of these pitfalls; the difficulty grading has as much poise and precision as the visual design.

Three minutes. No matter how busy you are, or how underpaid, Deadline is a game I can freely promise you have time to finish. And I can promise, that on the first or fiftieth time, it will still have things to teach. Even if it's only that it might be time to admit that a hardware mod is the only thing that's going to get you to the high score that your self-respect demands.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like