Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the latest installment of her design analysis column, Hide&Seek development director Robertson delves into the complex but thrilling puzzler SpaceChem and discovers how games can elicit creativity from people who would otherwise resist traditional art forms.

[Five minutes of... is a series of video game investigations by Margaret Robertson, former Edge magazine editor-in-chief and current development director of social game studio Hide&Seek. Here, she explores what five minutes of play reveals about a particular video game, this time focusing on the elaborate, difficult-to-play and surprisingly thrilling PC title SpaceChem.]

There are stories you tell that you shouldn't tell. I've got a great story I tell a lot -- inspiring, funny, life-affirming -- that I shouldn't. It's a story about why I believe creativity is important, and about why I believe making things is hard. I could tell it here, but I won't, because it's largely about pooping, and it turns out that pooping stories are the stories that you tell that you shouldn't, even when they're great.

Instead, let's talk about SpaceChem. It's a game I realize I don't know the genre for. A blueprint puzzler, maybe? Its heritage is in Pipe Mania and Deflektor and The Incredible Machine, and you might have last played one in Train Yard.

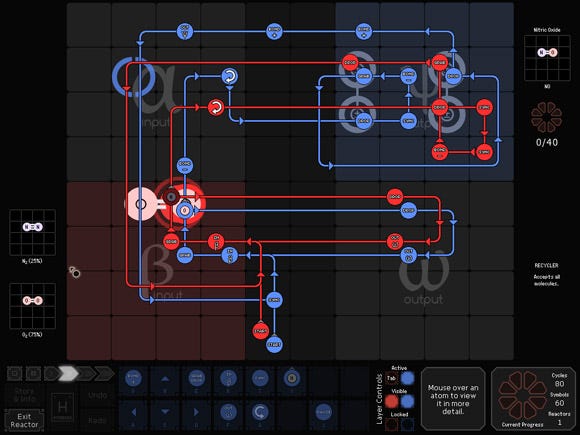

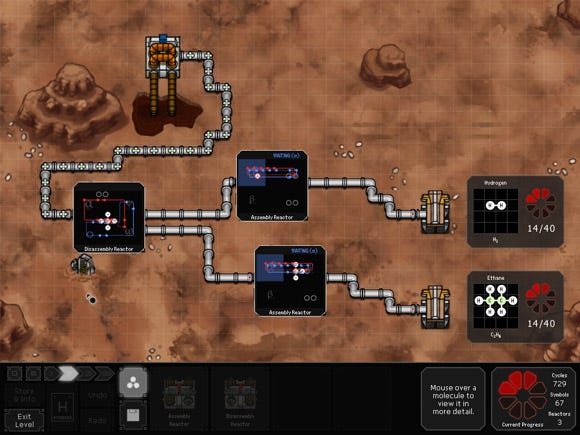

In SpaceChem you configure the inside of a series of chemical reactors. A configurable system of circuits moves atoms about, bonding and breaking apart molecules, reconfiguring sequences of substance.

Your tools are pretty restricted -- broadly speaking you can pick things up, break 'em or bond 'em, and dump them in the output -- but the combinatorial possibilities are clearly colossal.

What the game asks you to do with these tools is the impossible. It's a long time since I've played anything so astonishingly dispiriting. Each level teaches you a new insight, and then the next level presents you with a problem which is in no way solvable with that insight.

Instead, it gives you a spatial, procedural and logical task which transparently exceeds the tools at your disposal. But you've come this far so you sit and chip away, and fail and flounder until you happen upon another insight, which unlocks for you a next level that is in no way solvable with that insight.

This, now that I've written it out, probably doesn't sound like the five most thrilling minutes you might hope to experience in a life well lived.

But, of everything I've played -- with the possible exception of an incident involving Alien Trilogy and a poorly-secured poster -- I suspect SpaceChem gives me the strongest readout on heart-rate spikes and coritsol levels. I've played Resident Evil 4 hooked up to skin conductivity detectors and can tell you with total confidence that it's got nothing on SpaceChem.

The five minutes balanced on the fulcrum of finding a solution are as exquisite an emotional roller-coaster as you could ask for.

The first prickly suspicions that you're close to an answer are actual physical sensations, sweeping up and down your body. There's a slight surge of panic as you worry that your optimism might jinx it, a tang of fear as you anticipate the crushing pain of yet another failure.

Hope builds as one, two, three, ten molecules hum harmoniously off the production line. The elation that follows is an actual endorphin rush. I'm not sure I've ever taken the idea that your heart could literally swell with pride seriously before, but there is a warm bigness in my chest that wasn't there before.

And, then, you get to share that glow with your rivals, your mentors, your pupils. It's likely that if you're playing SpaceChem you'll have all three, and that they'll all be embodied in the same people. It's a game that's hard to play alone, partly because once it's under your skin it's hard not to proselytize, and partly because before it's under your skin, you're unlikely to make much progress without some one-on-one tuition.

Your solutions are exportable as video files, and it's impossible to resist the urge to send them on, as tokens of gratitude, answers to questions, implicit gauntlets.

So: no mysteries there. SpaceChem makes me feel good in a series of ways we now understand quite thoroughly as part of gaming's appeal. Competence, agency, social capital, etc. There are probably ten dozen post-grads completing theses which lay those elements out end-to-end as I write... and again as you read.

What's different at the end of five minutes in SpaceChem -- different from many other games which have given me those well-understood brain-chemical highs -- is that I've made something. Not just methane, or ammonia, or formaldehyde. Not just a machine. I've made a creative statement. I've made a joke, or a dance, or a boast.

My SpaceChem mentor finds pride in optimizing his machines so they don't use syncs. Syncs are little buffers that keep multiple circuits in time with each other. They can help you solve sequence and speed problems, but do feel a little like cop-outs. I am in reverent awe of those who can operate without them.

So, to begin with, I tried. There is something majestic about the purity of a sync-less circuit. I would fight my way to a solution, and then return to my functional-but-fritzy spaghetti junction and try to tease out a leaner structure.

And then I stopped. Partly, to be sure, because I was wilting in the face of the intellectual challenge. But partly because I like the pictures I make first time out. I like the crazy curlicues. I like how hard they are to read before you set them in motion.

I like the surprises they spring. I like the ballets that unfold as the molecules twist and rotate around each other. I like the crazy games of chicken I'm accidentally building, that barrel two circuits toward each other before a preposterous sequence of breaks and drops and grabs turns a head-on collision into a matador feint.

Here's what SpaceChem does that's so important: it gets me to make something without asking me to make something.

Asking someone to make something is one of the biggest impositions you can lay at someone's door. I can't think of a more threatening thing you can say to me than "Draw a picture of anything you like!" Except maybe "Write a story!"

You're asking, for a start, to take a little bit of some essential energy from me. Making anything costs something invisible but precious, something that's hard to replenish.

You're asking, too, for me to give you a statement of skill. The blanker the sheet of paper, the less there is to hide behind. There's no way for me to draw a picture without demonstrating how good I am at drawing a picture. And, for the record, how good I am at drawing pictures is not. There's no way I can hide that from you if I try to fulfill your request.

And then -- oh, the horror -- you're asking me to show you the inside of my head. You're asking me to volunteer a way in which I want to change the world. I'm about to introduce into it something that wasn't there before, and now I have to show you what I've chosen that to be. It's an anti-Rorsharch test which puts into pictures otherwise abstract, unspoken elements of my psyche. I would rather show you my medical records that draw you a picture.

Unless, of course, you were a game. Games fix all these problems.

Games fix them by mandating inadvertent creativity. They provide a framework that delivers you from the tyranny of the blank sheet of paper, of the anti-Rorschach test. They give you plausible deniability.

The pictures I draw in SpaceChem aren't a reflection of my skill at drawing. They're defined and restricted by the specifics of the puzzle and the nature of the toolset. They aren't revelations of how I want to change the world. They're accidents.

I wasn't chasing my vision; I was chasing the game's requirements. I can be freely, insouciantly proud of the things I create there, knowing that I don't have to be defined by them, just delighted by them.

There is huge scope here, that I'm only at the beginning of learning how to design around. There are very lightweight ways to put inadvertent creativity into games.

Super Meat Boy does it beautifully, with the chaotic spray of replays at the end of levels, which are complex documents charting your determination, your competence, your incompetence and revealing unexpected flair in your failures.

There are highly authored, constrained ways to do it, of which some of my favorites are ON's Grow games, which let wonderful nonsenses unfold from a series of oblique decisions that you make. What you're faced with at the end of a Grow game is a thing you made and yet didn't make. Which was made for you, but out of you.

It's something I'm thinking hard about in the games that we make that tie into people's real world activity. One of my frustrations with simplistic gamification approaches -- which I'm still going to be bloody-minded about calling pointsification -- is that they're so literal. They're all too often a one-to-one relationship: do a thing, get a point.

They fall on the wrong side of the distinction that Chaim Gingold draws in his Magic Crayons principle: if something does only exactly what we expect it do, it's probably a great tool but a lousy game. Games thrive when the output to your input is disproportionate and slightly unpredictable.

We want roughly the thing we expect to happen to happen, but we like it when the result amplifies our effort, and surprises us in ways that feel fair but exciting, that ignite our curiosity but maintain the cohesion of the system.

Whether it's something as abstract and self-contained as SpaceChem, or as integrated and significant as a real-world behavior-change game, there are ways in which games can enable freer creativity by constraining it.

I feel about those games the way a glass of salty water on a sunny classroom windowsill feels about the paperclip dangling in it. It's a framework that will draw dazzling crystals out of me, things that I can feel proud of but not responsible for.

In this instance, what games have drawn out of me is a way to talk about this stuff without telling the pooping story. For that alone, you owe SpaceChem a go. Just shout if you need a mentor.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like