Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this in-depth interview, thatgamecompany co-founder and fl0w designer Jenova Chen discusses his philosophy of abstract game design - and why making traditional games is "too easy" to dwell on.

Would you leave the Spore DS development team to co-found your own studio -- to make download-only games?

That's the choice thatgamecompany co-founder Jenova Chen made, and here, he reveals the philosophy behind his successful flOw, the most-downloaded game on the PlayStation Network, and what led to the creation of Flower, thatgamecompany's follow-up, slated for release later this year.

Conducted during Game Developers Conference earlier this year, this interview touches on Chen's hopes for the medium of games, including how Sony is uniquely positioned out of the three console manufacturers to help thatgamecompany realize its current goals.

So, I was going to ask, how has the PSP version of flOw been going? Who did the port?

JC: FlOw PSP is not made by thatgamecompany, it's made by SuperVillain Studios. At the time we finished flOw, we were like, "OK, we're gonna work on the next thing," right? And then, just, there are tons of gamers saying, "I want flOw to be on the PSP!"

Sony decided, "Maybe we should move it to PSP, but obviously you guys are not interested." And then they were like, "Well, you know, this group which we used to work with, they are really nice guys, and maybe we can get them to work on PSP for you." So basically we said, "As long as our [team] members are not distracted from this project? Fine, if you want to do it."

So basically, the project was lead by the senior designer and the senior producer from Sony, who worked on flOw. We really liked those guys, and they totally get what flOw is, so they will keep the product true after the port.

And since the port actually started -- it's really not technically a "port" anymore, because it's a remake, because the code that we had written for PS3 is just not going to work on the PSP. The assets are all too heavy for the PSP, so they basically remade everything, while trying to keep the same feel.

And as the development went on, more and more questions came to us, and our people became more and more involved; we definitely did more than we expected on the project. So, that's how the PSP version is, then.

Are you satisfied with it?

JC: I haven't really played the latest version, so I can't really say anything. We have a lot of feedback and improvements; I don't know what the latest version looks like.

It's mainly Nick, who is the other author of the original Flash flOw, and lead designer on flOw PS3, so he's basically handling that. I am just putting my mind on Flower right now.

What is your process like, at thatgamecompany? From concepts, do you then do prototyping?

JC: Yeah, this is technically the first original IP for thatgamecompany, because when we first started working on flOw, the game was already there, you know? Like the Flash game, the design, the artistic style, it's all there. So the first project we did was more like, we needed to learn how to use PS3, and we need to buff up the look and the sound to make it look like a PS3 game.

JC: Yeah, this is technically the first original IP for thatgamecompany, because when we first started working on flOw, the game was already there, you know? Like the Flash game, the design, the artistic style, it's all there. So the first project we did was more like, we needed to learn how to use PS3, and we need to buff up the look and the sound to make it look like a PS3 game.

So Flower is the first game where we start from nothing. So I started the concept from several concept drawings I did. We always start a game based on a feel that we want to accomplish; that we want the player to feel a certain way. But if I can't tell what that feel is, and if we are not going to that feel, it's like, "Oh, I just missed my progress," right?

In fact, the feel has changed in its nuance. In the beginning I had a very vague direction: "This is the feel that we want to achieve." Then as we develop more and more, we realize certain specific feelings are impossible because of the limitations. But then, the rest of them are still possible. So the game itself kind of grows.

That's the fun part of video games. It's not just art. It's not like a movie, where if you have a script, everything is set. But video games, you have your team with you, and then you have the technology you are developing. What if the technology suddenly does not support what you originally envisioned in the design? Then you have to change your design.

So the game is evolving on its own right now, so we kind of just guide it where it's necessary, but it moves by itself. But, in general, it's like we are driving a car to the East Coast, but are we [going via] Kansas? Are we taking the northern side? We don't know. We are kind of in the middle up there.

I see. And so, you go through the concept phase, and then the phase you're in now -- would you call it prototyping, or would you call it...

JC: Well we've passed our prototyping. The concept started more by myself. Because at that time, people were still finishing up flOw; I am the only guy who has time. So I basically prototyped myself, and came up with a series of prototypes, and said, "Hey, this is what I envision, and these are the key technologies that I hope we can have."

Then, once the team started, the whole would basically divide the production into the prototype phase, and then the production phase. We finished our prototype phase in six months. It was a long prototype phase, because we originally thought the production would not be that long; probably another six months, and then we could be done. We hoped that we could finish the game in a year.

But after the prototype phase, we realized that there are still a lot of unknown things, because this game is just so different. But we've started production now, and we've started making levels, but as we are making levels and doing play tests, we notice more issues coming up, and to solve them, it requires more prototyping.

So it's more like an iterative process rather than, "Hey, we design, and finish this, and then we execute." I think it's just not going to happen to any innovative games. You know, if it's something new, stuff just changes all the time.

Do you find your process is still somewhat getting figured out, since you're a newer company?

JC: Well we've started this process since we were working on a school project -- we had the [first] game, the Cloud game... You know, it's like, at the beginning, we start, we have enough prototypes, like 10, but then as we start production, it's just taking longer than we thought, and then it requires more prototypes.

It's basically like what we were taught in school: design, production, and play test; redesign, production, and play test; redesign, production, and play test. It's an iterative process. At the beginning it's really big, it's a very vague design, but then it's like a pyramid, and in the end it's a really small iteration.

Refined.

JC: Yeah. Which is not really like the process in big studios and big projects. We kind of -- both Sony and us -- we are all learning, because through flOw, we realized that it's not going to be a very straightforward process. So, I think right now, even though we are in production, there are still a lot of things coming up. But everybody understands it. So it's cool that way.

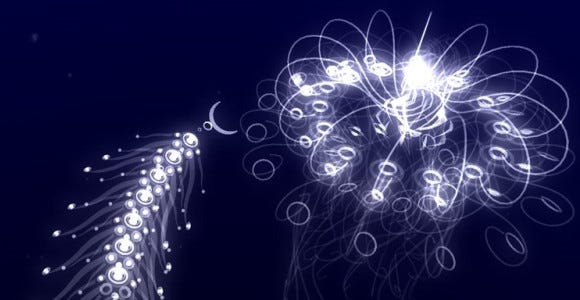

thatgamecompany's flOw

Is it at all frustrating to be making the same misjudgment each time? Like when you said you think, "Okay, it's going to take this long," but always it takes way longer.

JC: This time we actually learned that, because during development, people crunched so much. Even though I was not there most of the time, I can feel it. We originally predicted that we could finish flOw in six months -- in four months, actually. We started production in June or July, 2006, and at that time the PlayStation was launching at the end of November. So we were like, "We're gonna have to catch up so we can be a launch title!" So that's four months, right?

And because nobody has worked on PS3, well, it took me two months with Nick -- we both had no experience in Flash at all; we learned Flash and made the game. And so, because we were also in school, we figured if we really calculate all the time we spent, it's probably three weeks. So, "OK! Definitely we can get there! Now we have five people! We have four months! Sure! The game is already done, and everything's all there!"

But in the end, the game took us eight months to make, and we only delivered half of the original design. So it's like we 400% under-delivered. So you can imagine how much crunch the people had. The launch date had been delayed several times; each time it's a big morale hit.

So from that experience, the team members... Me? I haven't been through that hell, so the team members will always be more conservative than me. And I think because they have a more conservative attitude this time, we didn't crunch at all. We always delivered in time. It's like 40 hours a week -- you know, 50 a week for some programmers, but we're proud that so far we didn't crunch at all.

That's good.

JC: But, you know, the games definitely took longer to make, but we are not going to kill anybody.

Are you still going to be able to make one game a year?

JC: Well, we hope to, but flOw was launched in 2007, and we are still positive to launch the game this year. But 12 months? I think we already broke that. It's just impossible, because... I think I am just too ambitious when I start a project. I say, "Well, you guys should be done," but then it turns out to be a much more difficult project.

So even though these games are kind of smaller in scope, it's still taking quite a while.

JC: Yeah, I don't know if you were in the PixelJunk talk yesterday; I think they have a much more practical plan, and much better understanding of what they're doing. Six months a game, and they all know those game genres very well, right?

So during our production, because we are working on a game nobody has ever known -- even me, I am not sure what the final game will be like -- so it's like walking in the mist. While those guys probably, you know, "Well here! It's right there!" and just dash to there.

But so while we are working on the Flower game, it's kind of frustrating, so we actually do game jams, where we will say, "OK, let's do this weekend game jam, 24 hours, let's make a game!" And it's the most violent, fun game you could ever imagine!

The game was so fun that we just kind of spread the game internally among other Sony developers, and a lot of people became addicted to that game. But then, are we ever going to make this game into a real game? Probably not, because that's not our company's goal. But I think it is helpful to adjust just how you feel.

I was actually going to ask if you had ever wanted to make a traditional violent type of game.

JC: It's just so easy to make, you know? We all have a really good sense of how it should be fun, how it's cool. I think it's just too easy for us. And, also, if I just want to make violent games or fun games... It's not to say that fun games are bad, but I could just go to work for Blizzard, or go to work for Maxis. And they make fun games, they make creative games. I could get a lot higher pay, and a much more stable job. Why not?

Why would I start a company just to make the same kind of game which I can get a much better life in another company? You know, the reason we started this company is because nobody is making this kind of game, and to expand that emotional spectrum of video games -- having more people be able to enjoy video games. The only way to do it is to just do it yourself.

We tried to just convince big publishers like EA or other people to make games like Cloud... It's just almost impossible. So, yeah, we just realized that unless you are a company, and have done great games, then they will say, "OK, we might take the bait, and risk giving you the budget to make games like that." Otherwise, as an employee, you can't really change anything.

thatgamecompany's Cloud

And while, for example, Maxis' Spore is awesome, Spore is not really the game that thatgamecompany is set up for. So after working on it for a while, even though the game is so fun, and everybody there is so creative, like, basically prototyping every day. It's like the perfect job for a game designer -- I still don't know why I dropped it. (laughter)

I think it's because, you know, when you play games, you have a goal, and every action you have has a clear response and reward to tell you, "Hey! You're closer to the goal!" Whether that's an experience bar, or your cash that you're collecting, I just felt like no matter how hard I worked at Maxis, I'm not getting closer to the goal that I'm looking at.

So, you know, I think I just want to create more of a contribution for the industry. If I stayed with Spore at the time -- I don't even know when it's going to be done, but finally they released the launch date. I just thought, "If I left at this moment, and started creating a new game, I might be able to create a game before Spore even launched." I think we still have a chance!

So, [a new game] plus flOw. I just think having two more games for the player is better than... to leave a company before the game is done? Yeah, it's bad for Maxis, but I think it's better for the gamers; for everybody. Just having more games for the gamers -- more games with a different feel.

It seems like you're trying to go for emotional response from people without the use of narrative -- or traditional text-based narrative.

JC: Friday I am going to be in the [GDC] roundtable, and I am going to talk about how games, most video games, have a lack of intellectual content. It's not like there isn't -- Metal Gear Solid is very intellectual, you know, and BioShock, and Shadow of the Colossus; they all have very intellectual content, but I think most of the content is through the story.

I can watch Metal Gear Solid and I can still feel intellectually entertained, but you rarely find a game that actually uses the gameplay to make you think. The only good example I can find is a recent game submitted to Gamma 256; it's a game called Passage.

I haven't played it yet.

JC: It's a very simple game. We can say it's not even "fun", but by performing the actions, it makes me think a lot about life. And I'm just intrigued by that. Not to say that Flower will be like that; I think Flower won't be as deep, because of the way that we designed it.

So why didn't we use story? I mean, I'm from film school, and I took screenwriting classes. We know exactly how to create an engaging story, but for us, we have the limitation, because the team -- we only have one artist. How are you supposed to create a story, or even a character? We don't even have the technology for character animations; how can we start the story? We just simply can't.

Also, to me, story is a tool, but not the goal of video games. In the past, when you say "entertainment" -- I mean, we care about entertainment more than story -- so "entertainment" in a sentence, basically, it's food for feeling. If you are hungry, you go to eat; if you are thirsty, you will drink; and if you feel sad, you want to do something to entertain yourself; or even if you feel too high, you want to do something to calm yourself down.

So I think story, or narrative, is a very powerful vessel to carry emotions. If you follow a story of a young boy growing up and avenging his father, that is a lot of investment, so when the revenge happens, the feeling that you have is much deeper than you feel if right at the beginning the boy kills the villain, right?

But story is only a vessel. If you want people to feel a certain way, you don't necessarily start with, for example, music. A lot of people use music for entertainment, but do you see story in music? Maybe in the lyrics, right?

And then, even for visual media, like animation or movies, it's just right now the most popular genre uses narrative structure, but you've seen experimental movies and animations which have nothing to do with story, but are really intriguing to watch, and make you feel a certain way.

One of the movies I really like is called Koyaanisqatsi. I don't know if you've watched that; it's a very artistic film. The film is about life out of balance, so it was shot probably in the 1980s, or maybe '90s, so it's all shot back in the city -- basically it's like a series of time-lapse...

What's it called again?

JC: Koyaanisqatsi. I think the GTAIV trailer is copying that --

But there's another one...

JC: There's Powaqqatsi.

OK. Baraka is similar, right?

JC: Yeah, similar. Just examples of movies like that. When I watch it, I just feel stoned. I don't want to sleep, I just want to look at it, and after the entire movie ends, it makes me think a lot. But did anyone say any line in this movie? No. Is there any character? No. But I feel that I have reached a cathartic moment, which makes me start to think about life.

And I think a video game can do that too, you know? Do you really need to use story? You can; I mean, you can have a very engaging story, and deep story, to make people think, but I don't think that you need story to do that.

I wonder if people invent their own story when they're in that kind of state. Watching one of those movies, your mind might subconsciously create a narrative thread through it. Do you feel like that sort of thing happens?

JC: Right. Yeah, I mean, narrative structure is how your brain works; it's not like someone invented story. It's like, if you want to describe something, the best way to describe it is to make it a story. It's not our purpose to break, and say that story is not the only way, but it just happened because we are a small independent group, and we have very, very limited resources.

And also me, myself, I am not a native speaker. If I really want to write good dialogue, I would be shooting myself in the foot. So I talk a lot about why I am making games like this. It's because I grew up in China, you know? I didn't grow up in Japan, right, so I don't really understand what Japan is like. I don't really understand what America is like. And the only people I know, I still don't know what they like!

So at this time, I don't have American culture, and I can't make anything relevant to football, or to cowboys, or to Star Wars even. So what can I do? I have very, very limited constraints. It's actually making it easier for me, because, well, I'm from the eastern hemisphere, I know what people like there in general, I know what Westerners like here in general, so I'm going to pick the most global feeling. The things that cross culture, and gender, and age, that everybody can relate to, and work them into games.

So that's why the Cloud game has to be about childhood daydreams in the sky; I think everybody can relate to that. The flOw game is more like the curiosity toward these microorganisms in the ocean; it's something I think everybody can relate to, but if you put guns on the flOw creatures, I don't think everybody can relate to that. So I picked Flower out for the same reason; I think everybody can relate to flowers and to nature. So, you know, that's kind of how I pick subjects.

thatgamecompany's Flower

Did you find that now that flOw is done, it's easier to work on PS3?

JC: Oh yeah, it's definitely easier, because the team has all learned a lot from flOw. So when we were working on flOw we didn't really use any SPUs, which is the biggest asset of PS3. Or, even if we used them, it was done by other programmers, not the programmers on our team.

But now, the team has caught up, and they've all started doing SPU programming. So that is really making a difference. We actually used the power of the PS3 this time. I think a lot of the other professional PS3 developers are probably going to laugh at us, because we didn't use it to 100%.

Well, I don't know if anyone is doing that.

JC: Well, we will see. I think the next game, we will do even better.

So you're going to stick with Sony for a while?

JC: Well at least the next game has to be for Sony, because of the three game deal. We'll see. I mean, right now, the world is changing so much; tomorrow is the Microsoft keynote, and I'm curious as to what they're going to say. I think it's related to the downloadable platform. [Ed. note: it covered the XNA Creators' Club.]

But so far we have had a great relationship with Sony. They totally understand what we are doing, and they appreciate what we are doing. I think Sony is much more interested in making games stylish and artistic; more appealing to adults. On that aspect, I think they are the same as we are. Because we are making games for people who are, I would say, like grown up gamers, who expect to see more out of a game than traditional actions.

So, we'll see. Once we are there, we might be working on PC games again, because most of our fans are from the PC game; they played flOw on a web browser, and they want to play more games on the PC. But for the future, we really didn't think that much, because we are focusing on the current game, and the next game is more ambitious. The idea is already started, but we will probably start deciding where to go next as we start making this sort of game.

Do you have any plans to bring out Cloud?

JC: Oh, Cloud, well...

To a console or some other platform.

JC: We started our company by pitching Cloud as a console game. But if we do it, we have a very ambitious plan to do it well. But right now, based on the team we have, and the technology we have, I think it's not going to be our next game. We just can't handle it. We will only do it when the time is right.

And also, it's like the baby we have; sometimes I just want to keep him there. If we have a better idea, we'll do the better idea. It's more like a safe protection. If we really run out of ideas, we really have no creativity, we will still have Cloud to make. Kind of like that.

That makes sense. And I suppose you would never want to outsource the game to someone else, like with PSP port of flOw.

JC: Yeah. The port was very, very difficult. We didn't think the port would take that much effort. They basically had to remake it.

Just like remaking it from Flash to PS3.

JC: Right. And for the next game, it's just impossible to run on any other console except the PS3, because the code is all written based on SPU. PSP is not going to handle it.

We always just want to make new games, but I'm sure that someone is going to tell us that, "Hey, it would be a good idea to make an expansion pack." Actually, the expansion pack of flOw is also done by SuperVillain.

For the PS3?

JC: For the PS3. So they are working on PS3 and PSP at the same time.

Was thatgamecompany in charge of what went into the expansion pack?

JC: The expansion pack, well, definitely the design of the creatures, and the feel, has gone through our designer and artist, but it's a collaboration. It's not like we have said, "Do this, do this, do this." It's more like, "We have these ideas, what do you think?" And they will say, "We don't like it," or "We like it," or, "We've changed it."

It's been a pleasant collaboration. I think they did their best on this product; it's just, unfortunately, that it takes that much more, while it could only take us a little time to make. That's the lesson we learned. You know, everybody said, "flOw is such an easy game to make," It's right there, it's just like Snake, we should be able to make it. But... (laughs)

Have you considered growing the company more?

JC: I always wish that we can grow bigger, you know, grow faster, but based on our experience on the current project, we have eight people on Flower right now -- previously we had five on flOw -- and when we reached eight, I feel there are moments where people are waiting, because there's nothing to do, or there are situations where the morale is low.

So we feel like maybe we didn't master how to work as a team yet; we shouldn't just keep growing, because then, the efficiency will be even lower, and then the consistency of the game will be even lower.

So right now we are just talking about how we should not expand for the next project; keep the same size, but try to raise the efficiency as a team. Because the most important thing that differentiates us from big teams is that we have a unified vision. We only have one artist, and one composer. So there's no way you can make art that goes in different styles.

And then we have three programmers, a game designer, and me as the creative director. So it's a very [unified] team, and that way we can make sure the game is like one entity. But if we just keep expanding, I'm sure it's going to go wrong.

Earlier I was commenting on a lot of games from big publishers, how they feel like it's made on a pipeline. Where the head, in the beginning, is awesome, because the people who work on it are great, but then the middle part is really lame because they slacked off, or the tail is really bad because they cut it.

So we used to use a metaphor: a barrel which holds water, a wooden barrel has all these pieces, and you use a frame to put them together. Each piece is for a different aspect of the game -- one is for the graphics, one is for the sound, one is for design -- and if any one of those is short, the water that you can hold is only up to the shortest part. And the water is the satisfaction of the player.

If you have terrible graphics, and everything else is great, the player will probably just keep saying, "Oh, the graphics suck!" But, meanwhile, if you have really wonderful graphics -- like real graphics -- but the gameplay sucks, they will still think the game is mediocre, because the gameplay sets the cap.

So, as a small team, there is no way that we can create a cap, a taller piece than a commercial game, but our goal is to keep every piece at the same height; so it could be even higher than some of the commercial games.

Yeah, that makes sense. You're only as strong as your weakest component.

JC: Right. So as long as we don't have the weakest gameplay or the weakest graphics, we will be better than most of the big games.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like