Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

With Bethesda's much-awaited Fallout 3 done, Gamasutra talks to game director Todd Howard to discover how the company has managed the franchise's evolution, from game world through rabid fans.

Todd Howard has been at publisher/developer Bethesda Softworks since the days of Elder Scrolls: Arena, the first game in the series -- released in 1994 for the PC. Now serving as game director of Fallout 3, it's his job to forge the twin legacies of that fan-favorite series and the lauded design of the Elder Scrolls series into one cohesive product.

Fortunately, Howard seems confident about his ability to do this. In the revealing interview below, he frankly discusses the contributions of the original Fallout games, as well as how developing Oblivion for the Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, and PC shaped his approach to Fallout 3.

Have you found making the game for multiple platforms simultaneously to be any more or less difficult than, for example, with Oblivion, which was on similar platforms but not all at the same time?

TH: Definitely much, much easier than Oblivion, because we've already been through it. So, Oblivion on both the 360 and the PS3, the games came out within a few months of launch, so you're not spending long on final hardware. Now we know how they work, and now we have enough code that works on those systems that it's easier.

So I'd have to say that it's easier, but still a significant amount of work, because we've changed a lot of things in the tech. It's a little more manageable, I guess I'd say. We know what's involved more, as opposed to, "I have no clue how this is going to work!"

Has the difference in balance of scale changed that process at all? I know that when I've talked to Pete [Hines] in the past, he's said that you guys are really focusing on a little less scope but a lot more depth. How does that play out, from a development standpoint?

TH: Well, the game's gotten a lot bigger, so it hasn't gone any differently there. It has almost as much content as Oblivion, but in different ways. One of the metrics we use: our data is relatively the same size -- we're using similar tools and things -- and the main data file for Fallout is much larger than Oblivion.

That tells us that we've put a lot of stuff in -- whether that's rocks, or whatever, I don't know; I haven't really analyzed it. But there's 20, 30 percent more dialogue in Fallout, so that's a lot of stuff to record. We've gone through the same process there, so that's still a ton of content.

Right, but that's more dialogue for fewer NPCs?

TH: Right, right, so you're getting a much bigger bang. A lot of specific voices, a lot of deep dialogue trees. We felt that that was a Fallout hallmark that we had to do.

As a game director -- and it's not like this is the first time you've done this -- how do you even approach something like this? It seems like such a fairly monumental task, on two fronts: one, it's just the issue of making a game this big, but you guys have done that before. But then there's also the issue of inheriting that IP. Not that you're doing it alone, but it seems like a pretty substantial undertaking. How do you approach that?

TH: The good thing with Fallout is that, from a workflow standpoint it's similar to what we do with Elder Scrolls, where it's very big, and it's an established world -- whether or not we've established it, or somebody else. The Elder Scrolls [world] is so big that no one person can remember it all, so when we think up stuff, we have to go research it. Like, "What did it say in this book in Daggerfall?" It's so much stuff. So we go through the same work with Fallout.

And frankly, it was a very nice change of pace for us. We were really excited to do the project. So, I think we're kind of used to doing it. I don't know that there's something specific I could point to, and go, "Here's how we go about it."

The one thing we do is we lay out the world. One of the first things we do is draw the map, and come up with the people and places. And the rest of it comes out of that. I mean, in Fallout, we knew we wanted to have vaults.

I usually come up with -- this is bizarre -- the first thing I always come up with is the beginning of the game, and the interface. I don't know why. Like, how does it start, and what's the interface. There's no reason for that; it's just what goes on.

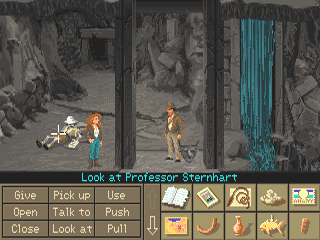

And we knew we wanted to start in the vault, and play through. I've always been interested in games that just start, and you play them; the character generation is part of the game. An early influence is Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis.

That's a great game. I love that game.

That's a great game. I love that game.

TH: I mean, you don't even realize you can click on the screen, and then you click, and then [Indiana Jones] falls through [the floor], and more of the credits roll, and [you realize], "Oh! I'm already playing." I've always wanted to do it with RPGs as much as possible. So Fallout's is a lot of fun.

So we knew we wanted to start in the vault, and we needed a jumping-off point. We knew, jumping off, that you're attached to your father, and then he's going to leave. That's the thread.

And then after that, it's, "We're going to design the world." We're going to detail all the towns, and the people, and how they live, and where the enemies are, and what enemies there are; come up with a compelling world, and the rest of it kind of falls out of that.

And what's nice about all that is that you, by default, connect all the dots. When you're designing content, you know these things are there, so you can reference them. It feels tighter than if you sat down and designed a series of specific quests first. I'm inspecting set pieces, like, "Oh, this would be a really cool quest," and then we fit it into the environment.

I love the idea of "researching the world" -- of there being "research material" for worlds that exist purely in the video game space. I think that's a really fascinating concept. Researching for something that you didn't create in the first place must almost make it more like genuine research. You've got to go out and find things.

TH: Yeah, we actually got the hard drive from the server, from Interplay. They sent us everything. So we got to poke through that, and see all old design stuff that didn't make it, and what made it.

Another thing that I like to do is read old reviews. So, find old reviews of Fallout 1, because they're written in a way that doesn't have a lot of aging. They talk about how great the animation looks, and how crazy it is when you kill people. And if you were to just pop the game in and play it, those things wouldn't register with you now, but they registered then.

So it's like, "OK, this is what we've got to do." I tell people, "You could pull up a review of Arena -- the first Elder Scrolls game -- and just black out two or three words, and you wouldn't know which Elder Scrolls the person was describing." So we want it to feel the same -- but as time moves on, you've got to use different things to do that.

I imagine one angle you could get from that is isolating is difference between things that just don't hold up now because of the game design that's happened since that occurred, and the things that maybe were flawed to begin with.

TH: From an interface standpoint, I didn't even look at that. You know, "Well, it's not going to have the same interface anyway." Anyone who was talking about the interface -- yeah, my eyes went right through it.

Especially because that's one of your first [steps], as you said.

TH: Yeah, yeah, it's one of the first things. We knew we wanted to do it -- the [HUD] comes up on your wrist.

Do you think that's something that games should be trying to do more? That transparency of interface, character creation in the world, and the UI integrated more naturalistically?

TH: Yeah, I think as far as interfaces go, a lot of games, frankly, do it a lot better, in that I'm really anti-clutter on the screen, with information. So I think we could actually be doing a little bit better job with it being contextual. You don't need to have your health bar up all the time when you're in a city and not hurt at all; you know, examples like that.

But we felt -- and we tried to do it in Oblivion, where you're looking at your numbers a lot in an RPG, and going through your stuff -- how do we make that visually stimulating, and not just a spreadsheet? So in Oblivion, you have your guy there, and you can move him around... In the original design, he was going to be doing lots of stuff. He would react, the character would react to what you were selecting, but that never made it in.

I mean, Fallout was, you know, "Let's do it as the [wrist interface] Pip-Boy and try to make it just feel alive." But I think more and more you see games blurring that. Like, one of the examples that I've been using for the ease of play -- and you almost don't know it until you really look at it -- [is] Grand Theft Auto IV. I assume you've played it.

You put the game in, and it just starts. There's no menu. You never select "Load, do, yes." When you put it in, the game starts, the credits roll, and when you take it out and put it back in, it starts where you were.

Actually, all the LucasArts games were like that, by the way.

TH: The current ones?

No, no. The adventure games.

TH: Ah, yeah. So, I think I like that stuff. And some people, they want to see all the information on the HUD at once, but I, as much as possible, I like it to not be there.

One of the defining gameplay aspects of Fallout 3 is that you've got the VATS system, but you've also got standard real-time "shoot a guy" going on. I suspect that there was some impetus to try to bridge the two worlds. Fallout was rigid --

TH: Stat-heavy, turn-based.

And here's what people expect from a modern video game. I mean, is that how you went about thinking about it?

TH: I think that would be pretty accurate, actually. We just felt like we didn't want to make it appear [like a] "shooter." We wanted the ability for you to see your character doing really cool things that you couldn't necessarily do. We tried that line with the Elder Scrolls, too, but it's mêlée, so it's kind of, you know... You don't have to aim that well; it's just sort of "swing the sword and hit the guy."

And we're always conscientious where we don't want whatever we're doing to only be for people who can handle fast-twitch stuff. Where is that line for, "Well, I don't have the dexterity to pull this off. I want to play my character, and get into him, and have my character on the screen have the dexterity."

So again, we're kind of on the edge of that with the stuff we do. And we like that. I like being on the edge, because we play a lot of first person shooters. We play everything, and believe that there's not a specific rulebook for, "This is your genre, and this is what you can do."

You know what? I actually don't know many people who are like, if you ask them what they play, "I only play flight simulators! Nothing else! No! Ever! Nothing!" Not, "I only play first person shooters, without any menus."

But we're conscientious that some people aren't going to be really good at the heavy action stuff, so we try to walk that line. We felt that we knew we wanted to have you stop the game in some way. In the beginning we didn't know how. "Do we slow it down?" But we knew that once you said what you wanted to do, your character was going to do it, and make it kind of cinematic.

How does it feel, by the way, to have been making games for that period of time, and especially having one series that has existed for so long?

TH: Well they take so long, so it's not like we've made many games. It's good. I mean, I think we're lucky, in that the audience for what we do hasn't gone away. It's gotten bigger, if anything. It's gotten a lot bigger. So, we're fortunate that we can make those kinds of games that we want to play.

Like I said, those ideas are cool, and are cool forever. Playing a fantasy game where you get to make your own person and run around in an open world, whether that's a post-apocalyptic fantasy, or a more classic medieval swords-and-sorcery fantasy, that's always cool. It's gonna be cool a hundred years from now. It's just, can you present it in a fresh way and keep people interested in it?

As far as Fallout goes, this is sort of a sticky topic, but how do you guys deal with the crazy people who are on the internet?

TH: I mean, they're a lot less crazy than people think, actually. And there's a lot of noise, and we try pretty hard to listen to it. So, even if someone's ranting, and they're sending us messages on a certain thing, there's usually a common thread in that, and we honestly try to get at it.

For a number of reasons, we don't enter a back and forth debate, because that's not our job; our job is to listen, and try to -- as much as possible -- explain why we're doing what we're doing, and have the game ultimately speak for itself. I think it's a really hard game for someone to grasp from anything I say, or a screenshot, or -- I mean, you played it for 30 minutes; was that enough?

No.

TH: OK. So that's 30 minutes you just had -- to do whatever you wanted, for 30 minutes. So, my point is, it's hard to say something to express "This is how the game feels." We could say how it feels, but if you're pretty dubious about how you go about our stuff, I don't think that's going to prove anything to anybody. I'm not saying it should, either.

Some other things I found are that there are still a lot of games in parts of the world that are very viable isometric, turn-based things, and they've done really well. A lot of them don't come out over here, in America. If you pick up a European PC game magazine, you'd be surprised how many games like that there are. So it's still a very viable game type.

And I think a lot of people assume that we're doing things to meet some sort of demographic; they're like, "Oh, why is it first person?" I love first person. And I'll ask your opinion: When you step out of the vault, in first person, and see the [HDR light effect on your] eyes come in... Dude, that is a real moment.

Yep. I wrote that down. [flips pages] "Emerging from vault: gorgeous."

TH: Okay, so imagine that in isometric. Different league. And that's my opinion; there's no research that's like, "Oh, people like first person games, so we'll do it like this!" I think that it's awesome. And also, like I said before, with genres: It's not just me, but everybody at work, we play a lot of stuff. So, we play a lot of modern games, and we think most people can handle it.

And then if you look at the spectrum of games, if you look at every game coming out in the next year, on the platforms they're coming out on -- here's the spectrum [gestures with hands], from casual to crazy hardcore, and we're over here [points to hardcore end of scale]. Right?

So we're in the same spectrum that Fallout was when it came out. If that spectrum in gaming shifts over the next 50 years, we're not going to be off the curve somewhere. And that's not necessarily intentional; it's just human nature as we play other things.

TH: But the other thing is, that's what we do with them. That scene, we really try to listen to it. That's why we got to the, "Okay, what other games like this are there?" "Oh, no, there are more games like this than I thought." I'm still playing games like this, and I really like them.

The other thing is, when you get it, when you read your own forums and stuff, you're like, "Oh my gosh, this is just..." But then -- most people don't go look at other people's -- then you go to Blizzard's. Probably the most successful game maker there is.

Go to their forums. "These guys are TERRIBLE! What are they DOING?" That definitely puts it in perspective. But that doesn't mean that people don't have a point -- it's just how they're saying it.

Plus, you know, we've been doing it for a while. When we change an Elder Scrolls, whoa baby, you have --

That's true!

TH: You go from Daggerfall to Morrowind? I mean, that is a crazy change. And we got -- [makes noise of being strangled]. People forget. We went back to a lot of Daggerfall stuff with Oblivion, but now everybody who was playing Morrowind is like, "What are you DOING?" We can't win, you know?

That's a funny point, though, that you guys have a series that predates Fallout. And it predates Diablo, and all that.

TH: Yeah, and with, frankly, a much bigger fan base [than Fallout]. So, we're pretty used to it. And we're hoping that, hopefully after this game, Fallout will have an even bigger fan base.

Fallout's one of those weird cases, because probably the original base of people that played it was fairly small. I remember when it came out, and I was fully in the PC world -- completely-- but not everyone was. It's probably gained a lot through the mythic nature of it.

TH: It's true, actually. You know, the number of people who actually played it in '97 -- we got it all, when we wanted to make the game, and we went after the license. Like, "Nothing's happening with it, and we really want to make this," and the answer I was given was, "Well... Here's what it sold. Plus it's 10 years old."

Do you remember the numbers, off the top of your head?

TH: I do not. "Here's what it sold, and it's 10 years old. No one really cares that much anymore." And that was the appraisal [given to me]. And I'm like, "Well that's not the fault of the game! It's awesome!" Right? It's just, they didn't do anything with it.

It felt like, "Look, the pool of people who love that game are a lot of the press guys, and developers, and people who spread the word. They're at the top of the tower, and that trickles down."

And you, of course, have been part of that group for years.

TH: Exactly. So, you know, if we do this, and do it really well, the word will get out, and at least that part's going right. We'll see how the game ends up. But the word is out, and people want to see it; I definitely think we're good there.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like