Extended Fiction in Game Design: Metal Gear Solid and Emily Is Away

Part of my honors thesis on extended fiction in game design, this section focuses on Metal Gear Solid and Emily Is Away, two very different games that execute a relatively similar technique to extend their fiction and evoke parallel emotion in players.

“Entertainment takes it as a given that I cannot affect it other than

in brutish, exterior ways: turning it off, leaving the theater, pausing the disc, stuffing in a bookmark, underlining a phrase. But for those television programs, films, and novels febrile with self-consciousness, entertainment pretends it is unaware of me, and I allow it to.

Playing video games is not quite like this. The surrender is always partial. You get control and are controlled. Games are patently aware of you and have a physical dimension unlike any other form of popular entertainment. Even though you may be granted lunar influence over a game’s narrative tides, the fact that there is any narrative at all reminds you that a presiding intelligence exists within the game along with you, and it is this sensation that invites the otherwise unworkable comparisons between games and other forms of narrative art.”

-Tom Bissel, Extra Lives (Bissell)

The player of any single-player video game is always playing against a game that is handicapped. Computers are faster at the computations that video games require than any human mind could ever hope to be. The game could, at any point, defeat the player completely through perfect responses to their input. The game, after all, is processing and representing the player’s input on screen; it has knowledge of what the player’s avatar will do before they even do it. The game, as a system, knows at all times the position, the resources, and the possible actions a player could take. However, games are programed in such a way that they don’t utilize perfect information. The game’s antagonizing forces process limited data and make committed decisions to create realistic and conquerable challenges for the player. Games have set behaviors that the player can understand and then take advantage of, creating situations that give the player a sense of achievement. A simple example of this is the Goombas from Super Mario Bros. Goombas are programed to move on a set path and have set behavior. The player very quickly learns this set behavior, and how to exploit their preprogrammed routines to defeat or avoid them and progress. In diegetic terms, player input and processing are usually non- diegetic; in the realm of the game, actions taken by the player are diegetically represented, but the actual outside input, processing, and surroundings of the game that causes these actions are not traditionally diegetic.

In Metal Gear Solid, the game breaks this tradition on multiple occasions by including elements peripheral to the software as diegetic. In what has become one of the most legendary moments in video games, Solid Snake approaches the telepathic Psycho Mantis, both player and protagonist ready to fight him. But no matter what Snake or the player does, they can’t land a hit on Psycho Mantis. The telepathic antagonist taunts Snake (and the player directly), stating “I can read your every thought!” (Kojima). The game, represented by Psycho Mantis, is detecting the players every action, and “reacting” to those actions perfectly. The player is unable to defeat Psycho Mantis at this point because he possesses ultimate control over the situation, able to detect and react to the player’s every move. Psycho Mantis even asserts his control over the game’s systems by “telepathically” activating the rumble function on the player’s controller, making it shake and move around as if he is manipulating the real world from within the game. He’ll also turn the screen black, pretending that he’s switched the player’s television input. Psycho Mantis also reads the player’s memory card, quoting things like "You like Castlevania, don't you?"(Kojima) if the player has save files from Castlevania, Symphony of the Night on their memory card, and other game specific dialogue for different game save files (Figure 4). Psycho Mantis appears to be entirely aware of the surroundings of his digital realm and to be entirely in control of it. Furthermore, the player experiences the same feelings of helplessness that Solid Snake does; while the fiction may be stating the Psycho Mantis is reading Snake’s mind, the gameplay is forcing the player to experience the closest thing they can to having Psych Mantis read their mind.

Solid Snake receives one saving grace after struggling against Psycho Mantis for a while, in the form of a message from his commanding officer: “I’ve got it! Use the controller port! Plug your controller into controller port 2. If you do that, he won’t be able to read your mind!” (Kojima). To beat Psycho Mantis, the player must unplug the controller from the default player 1 controller port, and plug it into the player 2 port, usually only reserved for multiplayer games. Once this is done, Psycho Mantis exclaims “What? I cannot read you!” (Kojima), and the player can, from that point, damage and defeat Psycho Mantis. This set of mechanics implies that the player has confused Psycho Mantis, and thus, confused the game. The player didn’t defeat the game through in-game actions; they defeated the game by circumnavigating the game’s “logic”, where the game, represented by Psycho Mantis, was reading the inputs of the player through the initial player controller port and utilizing that to defeat the player. The player had to undermine the game’s absolute control in the digital realm by taking an action in the physical reality that the game can have no control over. Every button press, joystick push, or decision sent into a game’s systems can be overridden, undermined, or changed by the game’s logic; but the game cannot control the player’s manipulation of the PlayStation that the game is dependent on. This is a strange and fascinating commentary on control; the game controls all its logic, and every in-game action that the player takes is at the mercy of the game’s programming. But the game ultimately exists only in a virtual plane and can only exert so much control over our reality, one in which the player is in ultimate control. The commentary on the relationship the player has with the virtual world and the virtual world has with the real world, and the control dynamic involved, is an engrossing way to both somber and empower the player.

Similar instances occur throughout the Metal Gear series, and through other games. In X-Men for the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive, the final level of the game asks the player to “reset the computer” in the game, but then provides no in game action for the player to take to do so. The game has converged the in-game computer with the player’s game console, “and what the game actually required was for the player to perform a soft reset on his or her own Mega Drive by lightly pressing the reset button” (Conway). This is another example of extending the fiction to include traditionally non-diegetic systems related to the game.

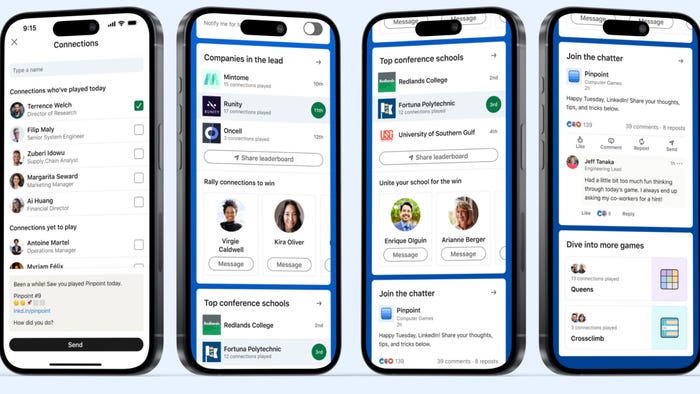

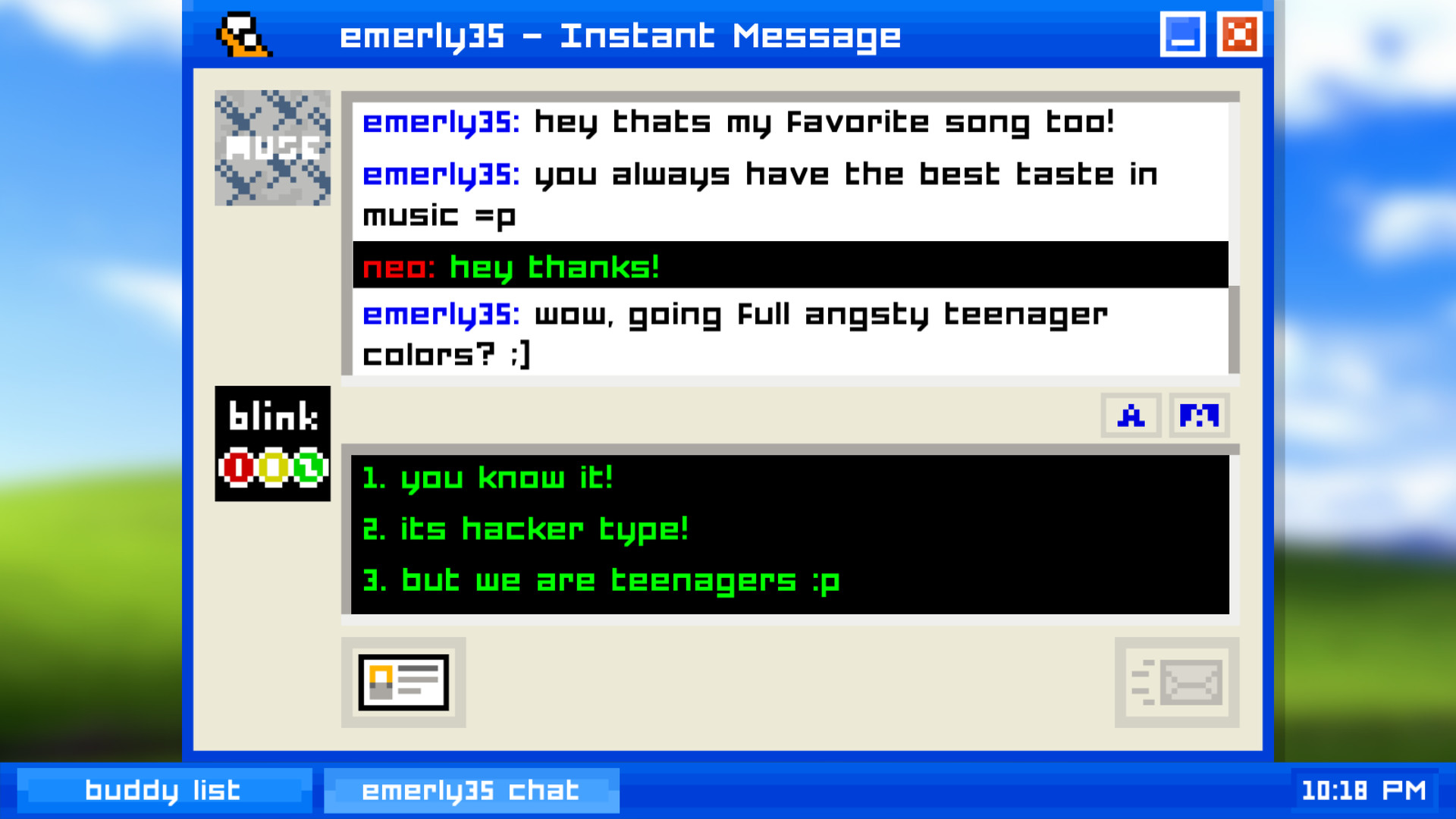

Playing with the ability of a player to control the game through extended fiction is a somewhat common technique in extended fiction game design; another example of this occurs in Emily Is Away. Emily is Away is a game that takes place in a simulated instant messaging window, recollect of the late 90’s program AOL Instant Messenger (known as AIM), with themes about the awkwardness of youthful relationships. It consists of a very simple control scheme and story, with simple dialogue choices to respond. However, near the climax of the game, the game’s controls are drastically altered.

Throughout the game, the player input to the game consists of two actions; the first is a numbered dialogue choice selection, where the player selects one of three options for the instant message they want to send. The second part requires the player to tap on the keyboard to simulate typing out the message itself; each keyboard press will print a character to the text box window, though the actual content is limited to the chosen prewritten dialogue choice. At the climax of the game, this input flow is interrupted; the player is presented with choices for dialogue, but when they attempt to type them out using the second half of the input process, their dialogue choice is typed out, deleted, and replaced with something else. The player is rendered helpless as their avatar can’t bring themselves to make the dialogue choices that might salvage their relationship with the titular character of the game.

The execution of this is masterful; the reality of the helplessness that the player experiences in this moment parallels the helplessness that their avatar is being portrayed as feeling; through forcefully restricting the player’s ability to affect the game and its characters, the player is pushed into experiencing the same emotions of helplessness that are preventing the avatar from acting. This provides a very different experience to that of the Psycho Mantis boss fight; Psycho Mantis causes loss of the protagonist’s physical self-control in combat, evoking feelings of helplessness in both the protagonist and player due to total lack of physical control over the game. The feelings of helplessness in the player in Emily Is Away, however, are caused by emotional helplessness of the protagonist, but renders the player just as helpless as they were in Metal Gear Solid. Both are communicated through experienced gameplay, instead of conveyed via narrative, but both deliver different narratives through almost the same methods.

My personal experience with this technique took place in the design of Justice.exe, a short mobile game developed for my When Machines Decide praxis lab. In the game, the player is given a binary choice of swiping left and right to sentence criminals to minimum or maximum sentences. The game is centered around the concept of machine learning in criminal justice sentencing, and so, in the end of the game, the machine learning algorithm that was being trained by the player through their choices is given control of decision making; the player is left with not control as the machine applies what it thinks the player was making their decisions based off of. This results in the machine sometimes sentencing more or less harshly based on race, gender, zip code, or other factors that most players would not account for in their sentencing of criminals.

The game diegetically removes control from the player in order to reflect the dangers of machine learning being put in control in our society. The game was simple, and perhaps not long enough to be successful in emotionally affecting the player a great deal, but it was a valuable experience in designing extended fiction and was reasonably successful in emotionally conveying the dangers of machine learning in criminal sentencing through gameplay.

This design technique is easily broken down; first, the player thinks that they’re in a position of control, which is almost a given for any player familiar with video games. Then, at some point, their position of control over the software must be brought into question, through taking that control away or manipulating it in some way. After that, if the goal is to re-empower the player, providing some unique, outside-the-box solution to manipulate the game’s digital world is effective in establishing the player’s position of outside control while still effectively imparting on them the message the game wishes to send. If the goal isn’t to re-empower, but to sober the player, then it’s unnecessary to give them a special action peripheral to the game to assert their control. The hard part is to frame this design style in a unique way, since it’s execution in Metal Gear Solid is so infamous, replicating it for the same purposes wouldn’t have the same shocking effect.

Extended fiction which plays with a player’s level of control over the game system is an intriguing way to cause emotional resonance in the player through gameplay. It heightens the immersion of the player, highlighting and critiquing their actual relationship with the game software in order to bring about much more existential narrative, both within the game and within the player.

To read other entries in this series, check out my Gamasutra blog http://gamasutra.com/blogs/AustinAnderson/1028242/, or check out the full thesis on my website at http://austinanderson.online/thesis

6 This action differs slightly depending on the different console ports of the games, but this description is regarding the original Playstation port from 1998. Other ports of the game execute similar actions or simulate those actions.

7 A “Soft reset” is a computer controlled reset of a machine, as opposed to a “Hard Reset” which is equivalent to unplugging and plugging a computer back in. Soft resets often retain some data hard resets do not as they control the shutdown process.

Bissell, Tom. Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter. Vintage Books, 2011.

Kojima, Hideo. “Metal Gear Solid.” Konami Digital Entertainment, Inc., 1998.

“Metal Gear Solid Wiki.” Metal Gear Solid Wiki, metalgear.fandom.com/wiki/Fourth_wall.

Seeley, Kyle. “Emily Is Away.” Http://Emilyisaway.com/, 1.0, emilyisaway.com/.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like