Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Monster Team talks about wanting to explore the lives of digital creatures, giving them their own agency outside of player wants, through text-based play.

The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

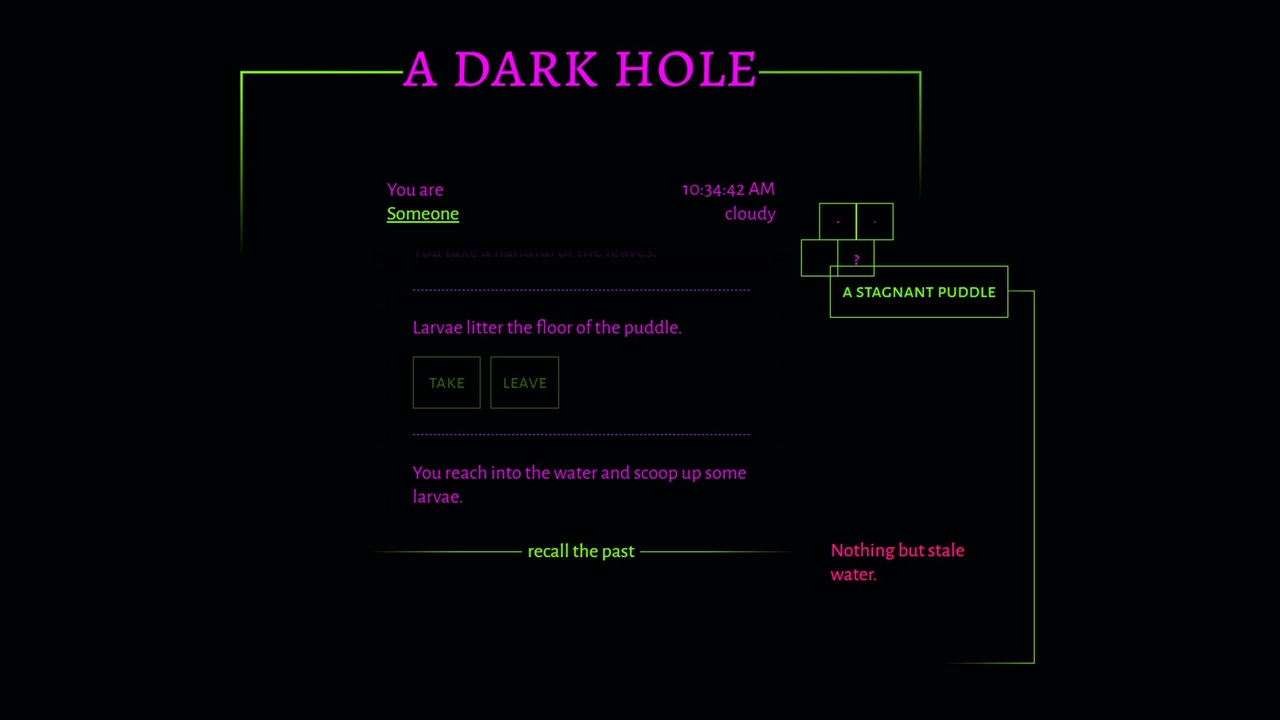

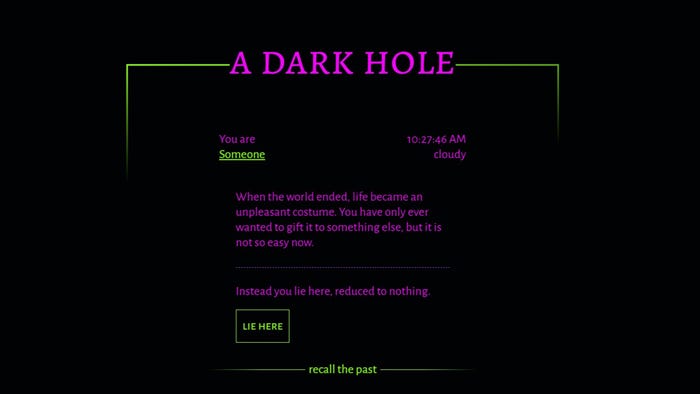

goodbye.monster sees us wandering through a decaying world with a tiny digital companion at our side, knowing all the while that this little creature doesn’t have long to live.

Game Developer caught up with the team behind this Best Student Game-nominated title to discuss the lives of past digital pets and how they helped inspire this experience, the ways they designed this game to reflect on those digital pets as actual beings rather than extensions of the player’s will and desire, and how text-based play would help enhance what they were looking to convey with the game.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing goodbye.monster?

Matt Mora, designer and programmer: I'm an independent game designer. I graduated from the NYU Game Center's MFA program last year, along with the rest of the team, where we started goodbye.monster. I worked on goodbye.monster as a designer and programmer, focused mostly on UI, animation, audio, and creature systems.

Rook Liu, narrative and art direction: My main role was corralling narrative direction, art direction, and cluttering our design doc for sport. I did most of the writing for the game, but everyone contributed to the writing at least a bit. If I had to boil it down into a role, I’d probably go with narrative designer who is also allowed to slap random art assets into the game and torment the populous.

Lorg An, technical designer and background illustrator: I worked as a technical designer and background illustrator. I implemented content for our locations, balancing negative space and content and using text to evoke a feeling of walking through space. A big portion of my job was also contributing to the visual development of the game by creating the bottom-page illustrations for our locations.

Beckett Rowan, backend programming and architecture: I’m a senior software engineer at Amplify, where I make educational games! For goodbye.monster, I did a lot of the backend programming and game architecture. I helped with the narrative direction, editing, and graphic design as well as managing our production schedule and processes.

What's your background in making games?

Mora: I've been working on games independently for nearly a year now. Prior to my time at NYU, I did some work in experimental and electronic music and instrument design, including some game-form performance pieces.

Liu: I went into the NYU MFA program intending to be a digital game lad. These days I have two card game publisher contracts and my other projects are in various states. My background prior to NYU was mostly in media analysis and art.

An: Before the NYU Game Center, I was working in mobile games on a live-service hidden object game and a bunch of indie projects.

Rowan: I’ve been working at Amplify for about 7 years now, and mostly I’ve worked on making browser-based educational games for schools that teach younger students math, literacy, and civic skills.

Images via Monster Team

How did you come up with the concept for goodbye.monster?

Rowan: I always tell people that my entire career is because of Neopets. I first joined when I was about eight years old and that’s where I learned about HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and how to make a community online. It’s always been at the back of mind. goodbye.monster was a chance for me to revisit the complicated feelings I have about growing up and moving on from that early internet experience, from knowing that my pets are sitting around immortal and starving on a server somewhere, to watching the site itself change hands and shamble on half-living through the decades.

Mora: The concept for goodbye.monster formed gradually through reconciling ideas from various interests and inspirations across our team. We wanted to make something web-based and text-focused, something a bit like (but also nothing like) Neopets and FromSoftware games, and a creature collector that eschews collection. We found unifying themes in transience and death, but never really adhered to a single concrete concept.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Rowan: We often say that our game engine is the browser! goodbye.monster is built in JavaScript using Node.js for our server and svelte as our frontend framework. For hosting and prototyping, we relied on glitch.com, which let us have multiple versions of the game live for testing at once in addition to making it easier to share and remote pair program together—not all of us were strong programmers when we started! On the production side, we used a lot of Miro and Notion to organize everything, which really helped us through some chaotic remote work periods.

What interested you about exploring the lives of digital pets with goodbye.monster? What was it about them that made you want to make a whole new experience about caring for these creatures until the end comes?

Liu: Digital pets in most creature collectors are an expression of the player’s own identity. Like someone’s Pokémon team or their favorite Neopets, they’re less about caring for the actual creature as they are an expression of your own taste. We wanted to explore removing the player’s control in a game about caretaking, as real children are not expressions of your own identity. One of the ways we removed control was just by having the creatures die. We wanted to explore connection but also establish that you and your creature are alien to each other, as we are to most other creatures and sometimes to other people. Companionship removed from understanding, value removed from lifespan length, etc. We are just in each other’s lives until we aren’t anymore.

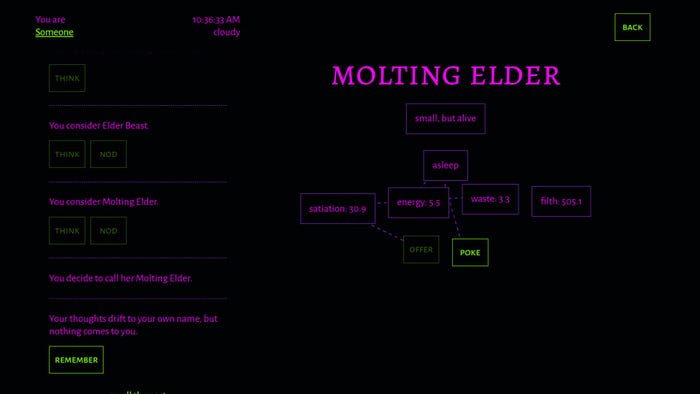

Mora: Most pet games and creature collectors, as much as I personally enjoy them, don't seriously reckon with the relationship between the players and creatures. Creatures in games tend to be tools for progression or vehicles for the enjoyment of the player. The player cares for them as far as they are useful or cute and they have little to no agency in the world of the game. We were interested in challenging this part of the genre and exploring a world and narrative that puts creatures before the player.

An: I wasn’t an original member of the team, so a prototype was already made when I joined. I feel like when I first played that prototype it immediately hit me like a piece of nostalgia: I used to play Nintendogs, Catz, and Petz, but here it is almost like the idea behind the game grew with me and shaped itself to my interests and fascinations.

What drew you to the text-based style for the game? What made you choose this for your play style?

An: Websites are information and information is text. I also have never worked on text-based games and it presents a novel challenge that encourages players to visualize the world using their own rules, so I was very curious about the process.

Rowan: Because I work on web materials for schools, I always have to be aware of accessibility as a legal requirement. That’s really changed how I approach my own games. With a text-based approach, I knew we could more easily make the game playable by screen reader. I also wanted to confront the notion that “players don’t read” and try to leverage short, mysterious text to prompt the user to enjoy words and really engage with their imagination.

Liu: We were interested in non-visual ways of perceiving the world. When players are presented with visuals, it’s not unusual for them to fixate on them and ignore all other information. So, to focus the player’s attention we decided that visuals would be secondary to text. It also made it easier to prevent the player from using the creature as an expression of their own identity, as a lot of that is motivated by visual aesthetics and the ability to customize them. Also, most importantly, text-based games are cool.

Images via Monster Team

What thoughts went into the visual elements of the game—the way words are laid out on the page to indicate place, the creature flitting around you, etc? Why did you add these to the text? And how did you choose which effects would add something special to this text-based experience?

Liu: How to express space in a web format was a point of continuous contention. At some point we just had a compass, but we landed on the current method because it would allow us to create little set pieces like the graveyard and long bridge without maps or full illustrations.

The creature running around was another way to explore the concept of the creature not existing just to serve you. It can get in the way of things you want to read and it isn’t possible to just put them away and ignore them while the player does whatever they’re doing.

The effects were done by Leslie Zeng! She was integral to the art direction of the game but chose to leave the team to pursue her own thesis. The effects were meant to add something to the experience without drawing too much attention away from the text. Having visuals without the players prioritizing only the visuals was fairly difficult in general.

Rowan: If you asked playtesters, they always wanted more visuals, more illustrations, more maps, just more to look at. So, this was one area where we went with our principles and ignored a little bit of feedback from the early tests. It did push us to give a little though. Many of our original prototypes had no visuals except text, but the particles and limited spot illustrations helped with the buy-in for our concept.

An: We were going off vibes and a guideline to have as few visuals as possible, but we had to use them in the most impacting way. The dithering effect on all the illustrations also contributed to the idea of giving the player an allusion to what the world is, only slightly guiding them to our vision, letting them visualize and imagine themselves as any text-based game does.

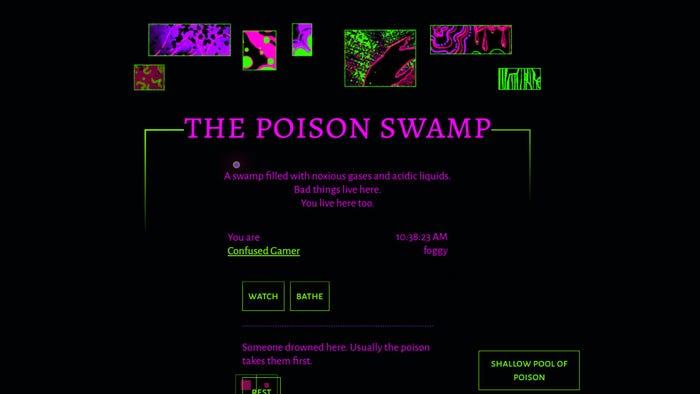

What thoughts went into the design of the decaying, gloomy place players explore throughout goodbye.monster? What ideas went into designing the world players would explore with their digital pet?

Liu: I wanted to answer the question, “What do you do when the life you thought you’d get to live is gone?” and the world design came as a direct result of that. You used to call these places home. Now the world has forgotten you as you have forgotten it. You are alien now to these familiar places. Nowhere to go and nothing to do. The world belongs to someone else—perhaps these creatures running around—but the dredges of what used to be still have time yet to rot and be appreciated. Also, oddly, a lot of thoughts about the Cambrian explosion went into the world building. So, in summary, it was a meditation on growing older combined with whatever strange interests we stumbled into along the way.

Rowan: One of our design goals was to confront the idea that the world is for or about the player. Not everything is about us, and eventually, we’re going to enter a new generation or a new era and find that things aren’t familiar anymore. The world belongs to these creatures and the new things making a life here, so sometimes that world is going to seem gross or hostile to the player. If it’s confusing or weird, we wanted it in the game as part of the landscape.

What ideas went into creating the "personality" and stats of the digital being? Into the limited ways the player can interact with it?

Mora: We've tried to approach "personality" as an emergent aspect of creatures that comes out in how players interpret creature actions and text. For example, instead of specifically trying to design how a "stubborn" creature should be behave, we've designed actions creature can take, like refusing a piece of food over and over again. That lets players interpret those actions, "stubborn" or not, as they come together in gameplay in a sort of procedural way. The limited and ambiguous connection between player input and creature output creates space for this interpretation.

Images via Monster Team

What do you feel makes us connect with this limited digital beings? How does having to care for these creatures affect us when they aren't real? And why do you think this still affects us?

Mora: If I can challenge the question a little bit, I'll say that not everyone does connect with the creatures. Caring for the creatures in goodbye.monster is a reflective task. Some players easily immerse themselves in the fiction and find meaning in the act of caring, others are reminded of real life experiences with a pet, and others still feel no connection to something they see as strange and artificial. We leave a lot open to player interpretation, which allows some players to really care but might also mean our game isn't for everyone, and that's okay.

Rowan: I would really agree with Matt. I believe a lot of an affective experience is buy in, especially in tragedy, horror, and other sort of cathartic experiences. It’s easy to say, “Oh I just wouldn’t have made that mistake!” in a horror movie and then get none of the payoff of the experience. We definitely had playtesters who resisted that buy in: sometimes just ignoring the creature and sometimes just being sort of cruel and flippant about them. Usually when we tried to prompt them for what would make them feel more immersed, they wanted more control. They wanted to dictate to the creature what exactly it could be to them in a very one-sided relationship.

And then we had playtesters who were big animal lovers who bought in immediately and got teary-eyed and loved it. If you sit down at the computer and you say, “Okay, this is a mirror and I want to see what it has to show me,” then we tried to design an experience that made room for that. Caring for something and feeling like you really matter in making a difference in its life are huge motivators for people, almost giving them a sense of belonging. Whether what you’re caring for is “real” or not only matters as far as you let it make any difference.

What interested you about exploring the deaths of digital beings? How did that exploration shape what the game would become?

Mora: Looking again at pet games and creature collectors generally, creatures are often unable to die. In exploring a creature-first design in this kind of game, that creatures can and will die was an early decision. In a way, we see creature death as an ultimate expression of their agency, completely out of the player’s control, who may have wanted them to stick around forever.

An: We all get to die, and seeing these creatures die is to participate in this cycle, which brings you closer to acceptance of your own mortality.

What feelings did you end up exploring while creating the game? How did creating this meditation on the lives and deaths of these creatures affect you?

Liu: This game infects every single game I’ve made since. That makes sense, as a lot of it was just me exploring themes I was already experiencing. I have a chronic disability, and disability disconnects you from normal day to day society. It becomes harder and harder to explain what you’re experiencing and to understand the experiences of others. I would have never gone into writing if it weren’t for my health issues at the time getting in the way of drawing. I can’t say I’ve found a satisfactory answer yet, for what to do when you can feel yourself drift away into alienation. Maybe it was a blessing to have ever experienced a “before” at all.

It was comforting to see these creatures dream and die as we all do.

Rowan: My wife and I started trying to conceive over the course of designing goodbye.monster and are now expecting our first child right when we hope to wrap up new features for the game. For me, this game has often been about exploring a radical sort of parenthood. I’m usually dissatisfied with how we treat young children in media, as if they either don’t have interiority or they’re complete evil aliens that could get you at any moment. By focusing on these creatures, it was a chance to make something where new lives are just free to exist, be how they must, have and express needs, disappoint you, frustrate you, confuse you, and make you cry.

Of course, as a parent you never want to outlive your children, but having the chance to sit with and think through designing that process has also prompted me to think about how to interact with the new lives around me and especially how to never take them for granted as some sort of legacy or extension of myself.

You May Also Like