Exploring A Devastated World: Emil Pagliarulo And Fallout 3

Fallout 3 lead writer and lead designer Emil Pagliarulo on the creative process of everything from the main game to DLC to understanding and implementing user desires -- and how people saw the game as an Oblivion sequel.

At the Game Developers Choice Awards during GDC, Fallout 3 picked two highly impressive awards: Game of the Year and Best Writing. In the wake of that, Gamasutra was able to sit down with Emil Pagliarulo, lead designer and writer of Fallout 3.

Pagliarulo, who worked at Looking Glass Studios and Ion Storm Austin before moving to Bethesda -- where he has worked on the Elder Scrolls games prior to Fallout. As he explains in the interview, his PC roots run deep -- and that appreciation for the classic tenets of computer RPG design has served as a guiding light for development at Bethesda.

Fallout 3's evocative post-apocalyptic wasteland and nonlinear gameplay has captured the minds of gamers, and here, Pagliarulo discusses the design decisions that lead to the game's choices, as well as the processes that the team has solidified since moving into the DLC portion of the game's life cycle.

You just won best game and best writing at the Game Developers Choice Awards.

Emil Pagliarulo: Yeah! We did. The shock that people saw was legitimate. I'm actually really shocked at the writing award. I'm shocked at all these award shows where GTA IV hasn't won. I expected them to win. I think the writing in GTA IV is awesome. For us to win over GTA IV, I can't get a bigger honor than that.

And as far as game of the year, we were coming from the DICE awards a couple of months ago, and LittleBigPlanet swept all the awards including game of the year. We were expecting that. So yeah, it was great.

On the note of recognition, I recently spoke to Jason Anderson, who was one of the original Fallout designers and is making an RPG at inXile. He said he played Fallout 3 and really liked it, but what I found particularly interesting was that what he most appreciated is how Bethesda is to an extent proving the viability of the large-scale single-player Western RPG. It's not the most ubiquitous genre.

EP: Yeah, I couldn't be happier that he feels that way. We certainly do. The talk these days is that if it's not massively multiplayer, it's at least multiplayer. Some people have been really saying that single-player is dead. For us, winning that award, I hope it sends a message that's, "Guess what? Single-player isn't dead."

Obviously, we're doing something that people want and they like. I'm really psyched he said that. I totally agree. I'm glad we get to do what we get to do.

A number of facets of Bethesda games are not particularly in vogue in a broad design sense -- lots of text, a relatively low proportion of scripted sequences, and so on. How do you know that stuff will work?

EP: That is true. I think about that a lot, actually. For a lot of console games in particular, it's all about level of polish. We know sometimes that our games don't have the production values of Metal Gear Solid or something.

We don't have those kinds of production values. That's just a fact. But what we do have with our games, partly because we're an older company and we've been working together for a long time, are very strong PC roots at Bethesda.

If you look at Daggerfall and Arena, those were both PC games. We're all sort of old-school PC gamers that added consoles. I think a lot of our sensibilities are based in old PC games. And I think that Fallout 3 shows that.

There are a lot of PC game sensibilities in that game. I think what that means for gamers is that there's a lot of inherent depth there. It's not just systems, it's not just graphics. It's like there's a little bit something extra.

Our goal, anyway, is to capture a little bit of that magic of PC games. I think a lot of our audience is in that same category. They see what we do and appreciate it. I think there's definitely some of that going on. There's not a lot of that on the console, so it's almost like we have that novelty quality, too. We have those niches -- the giant open game niche, and also this PC game novelty niche, too.

There is that classic PC game goal of immersing the player into a systemic environment with a high degree of agency, as opposed to the more traditional console goal of immersing the player into a carefully-constructed experience. Obviously, there are exceptions to both, and both approaches have a lot of merit, but I think there's some kind of abstract vibe that traditionally separated the two.

EP: Yeah, that's very fair, yeah. In those PC games, the pacing is controlled by the player a lot. And when you immerse the player in a world, you want them to explore it at their leisure. In Bethesda games, you're not going to find a lot of timed sequences, or a lot of linear levels where you're beating up the bad guys.

How much do you think about balancing demands on the player's investment in terms of the main quest and the side quests? Although you can't dictate the pacing, do you try to guide it at all? Across different Bethesda games, the critical response has differed in terms of which is more engaging -- the main quest or the world and what you can find in it.

EP: Structurally, Oblivion and Fallout 3 are very similar. We have our main quest, and the main quest is where we like to tell our story. But all of the side quests that we do aren't really connected to the main quest in any way; most of the time, they're not even connected to each other. They just fill in the world, and they're just out there for you to find.

That's one of the benefits -- the player can jump between one and the other at any time. It's interesting how we concentrate our time, because we spent a lot of time working on the story for the main quest and its polish and stuff, but at the same time, we have almost two games there to make that the player's experiencing.

It's impossible for us really to track what that experience for the player is going to be. Do they do two quests of the main quests, do thirty hours of the side quest, then come back and finish the main quest? Do they just beeline through the main quest? We find that most people don't do that.

When we design the game, we tend to structure it so that the player traverses the map. We'll actually move the quests to achieve that: "Let's put this over here because when they're on the main quest, they're going to run into this location." They're two separate things, but they're symbiotic, too.

And due to the nature of the world, there are times when you can inadvertently run into a clue or mission that most people probably won't find until later in a quest line.

EP: Oh god, yes. That was a decision we made. If the player wants to explore, you can actually cut out probably 10 to 15 percent of the main quest by finding stuff early, like the dad character. The first quest is geared toward finding him, but if you go off and explore, you can still run into him.

Presumably, that's necessary if you blow up Megaton right off the bat.

EP: Right. Some of the things really aren't necessary, but we still let you do them. We just say, "You know what? If the players out there are exploring and they want to find this stuff, let's do it."

With games like Oblivion, or certain titles in the GTA series, you hear a lot about players just going in there and spending all their time goofing around in the world and not resting as much on the main storyline. Although people have explored Fallout 3 a lot, it seems less of one of those "endless" games, probably in part because it has an ending.

EP: Yeah. With Oblivion, we knew that the gameplay was going to offer, if you did "everything," 200 hours, right? We figured Fallout was probably more like 30, 50, 60 -- anywhere in that range.

But I think what we're finding now is that one of the reasons people complained about the game ending was because they wanted to keep playing in the world. Now we're finding people, especially with the DLC, playing 60, 70, even 80 hours. And on the PC side, all the plug-ins and mods help with that.

So, yeah, people like to just live in the world and screw around. It's funny; one of the designers, Brian Chapin, has his house in Megaton. Todd Howard came by and we were watching Brian's house during his playthrough at work, and he'd found every single book that he could find and put them in his house. Every book, every skill book.

We just live in the world and screw around a little bit, play with the Havok physics, and make little contraptions, throw stuff in the water, throw grenades around to watch things all blow up. We realize how easy it is to just get lost. Because it's a toy in a way, too. People like it as that.

With the upcoming DLC, you guys are actually going to change the ending, right?

EP: It's the third DLC, Broken Steel. We haven't said exactly how, but the game doesn't end anymore. We looked at the ending cutscenes, we looked at the states of the characters, and we debated, "Should we do this?"

Todd Howard and I had a conversation, and [realized] it would be more seamless than we had first thought. We looked at it, and said, "You know what? It feels pretty natural. It almost feels like this is the way it should have ended to begin with."

So, the game doesn't end, and it raises the level cap to 30. It adds new perks, new weapons, and new quests, too. And obviously it's a new quest where you're dealing with the Enclave. You're working with the Brotherhood of Steel to wipe up the Enclave remnants once and for all.

That must be bizarre from a design standpoint; I doubt that kind of decision gets made in games often. There are new cuts of films released all the time where the ending is changed, but not so much in games. It's almost like a mea culpa here.

EP: "Mea culpa" is kind of the right phrase, actually. Because, you know what? We've said this before, but we ended the game because we thought it should end. Other games end. And we wanted to balance it to level 20.

And while we realized that people saw this game as a sequel to Fallout; they saw it just as much as a sequel to Oblivion, and Oblivion didn't end. People expected that from us. Even when they reached the level cap, they didn't really care -- to them that was was secondary to adventuring more in the world.

How much does the development process change post-release when you move into DLC? I assume it scales down a lot.

EP: It's significantly scaled down. They're sort of micro-projects. People would be surprised at what goes on -- you come off a big project like Fallout, and it's a lot of work for the people who had just come off the game. It's not break time.

It's actually sometimes more work because you're working in these accelerated schedules. You're thinking, "Holy shit, I just have this much time to get this done? I gotta get cracking!"

It's certainly not the case where we took stuff out of the base game. We had meetings after Fallout 3 was out, and decided what the content was going to be. But Broken Steel, in particular, was a really interesting case study -- almost like a case study for the industry, I think.

You talk about player feedback -- so people didn't like that the game ended. Three or four years ago, if people didn't like that the game ended, we'd say, "We'll take that into consideration for the next game."

Now, you're reacting to that feedback almost immediately. We're able to, months later, respond to that player feedback and put out DLC. For us, it's been a tremendous success. We're actually surprised that more companies don't do it, but we also know how difficult it is to do.

You looked at a pretty wide spectrum of DLC size with Oblivion, and you seem to have decided on somewhere towards the bigger end -- but not on the upper end of that direction.

EP: Yeah, well, we looked at what we'd done before, with something as small as horse armor and something as big as The Shivering Isles, we realized that actually production pipeline-wise and success-wise, the Knights of the Nine expansion we did for Oblivion was a good model for us.

Shivering Isles was a major project, and horse armor was -- well, we were one of the first people to do DLC, so it was an experiment.

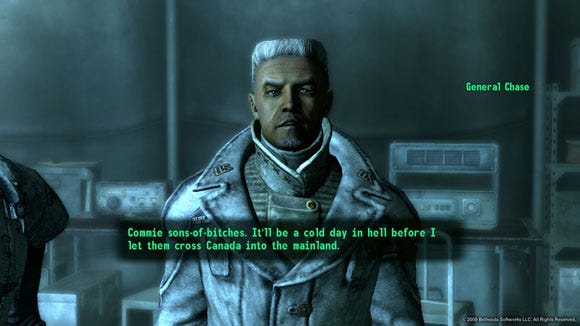

We used the Knights of the Nine model of small, well-priced, additional quests with new stuff. Look at Operation: Anchorage -- four, five hours of gameplay. People criticized it.

It is linear, it is more action-based, and it doesn't have the role-playing stuff. We knew that. We knew some people wouldn't like it. It was a conscious decision for us.

But we don't want to do the same stuff. We wanted to do something different and use our tools to put people in the snow and give them a different type of experience. You get a quest and you get new weapons. We're not selling that stuff parceled out. We feel like we're giving the player a full package.

One thing I remember people liking about Shivering Isles was that it brought a really different visual setting into the game, with the two split environments. It sounds like Operation: Anchorage had partially a similar goal.

EP: Yeah, it does. It depends on the genre you're working in. In Oblivion, when you have a game where you can include the Plane of Madness, there are a lot of creative liberties you can take there. In Fallout, using the virtual simulator technology was our gateway to that. It's the weird stuff.

But we don't want to overdo that.

Right -- "Now, here's the lava level!"

EP: Exactly. At first, we had talks like, "Should every DLC be the simulation?" But we decided no, because you want to bring new stuff back with you. You want a new experience in the world.

The Pitt DLC is a good example. We thought, "So, this is what D.C. looks nuked. What does everything else look like? Maybe we can explore that. Maybe this place has a little more vegetation. Maybe there's some old scrapyard over there." It's been fun.

It must be an interesting and unique experience, but also a potentially limiting one, to have your game basically set in an alternative version of the area your office is located in -- "What crazy thing could we modify from our familiar surroundings?"

EP: Yeah. But with Fallout, it's not completely grounded in reality. There is the tinge of madness there. We can always go out in the weeds a little bit, and then there's the whole 50s pulp thing we can explore. There were a lot of avenues for us to look at. But the Pitt seemed really natural, because we had talked about it in the base game.

And thematically, The Pitt plays a lot more on the shades of gray. We explored moral ambiguity a little bit in the base game, but we were just starting to get a feel for it.

I think as we wrapped up production, we thought, "We understand this now. We get it, and we want to do it." In The Pitt, it's much more, "What is good and what is evil, and which line do I walk?"

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)