Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Road to the IGF 2022: Last Call is an autobiographical game about leaving a violent relationship, packing up boxes and responding to poetic memories as you prepare to move out.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series.

Last Call is an autobiographical game about leaving a violent relationship, packing up boxes and responding to poetic memories as you prepare to move out. Players are asked to respond, with their actual voices, to these memories and thoughts, calling up a physical reaction of understanding as you prepare to leave.

Game Developer spoke with developer Nina Freeman about creating the IGF Excellence in Narrative nominated game, the challenges that come from creating a work on domestic violence (especially their own experience with it), why it was so important that the player speak their responses aloud, and how the mixture of art styles capture a sense of chaos, and finally peace, as the player progresses through the move.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Last Call?

Nina Freeman, co-developer of Last Call: My name is Nina Freeman. I'm a game developer and a streamer with a focus on narrative-driven games. I am one member of a two-person team who worked on the game. I primarily worked on design, writing, and code, and the story is based on an experience from my life. My spouse, Jake Jefferies, worked on the art and code and helped with design.

What's your background in making games?

Freeman: I've been making games for... 7 or 8 years now, wow! I have always focused on narrative-driven games, often drawing on my personal life. I am probably best known for my work on small vignette games, including Cibele and how do you Do It?. Jake's background is in the fine arts and game development. He previously worked on digital art pieces with various artists in New York City. Jake and I, as a team, have previously worked on a game called We Met in May, which is a comedic collection of vignette games about dates we have been on.

How did you come up with the concept for Last Call?

Freeman: Last Call actually began as a way to break me out of writer's block on another game we're working on. I've been working on (and still am [laughs]) a horror game with Jake for about a year, and I was feeling stuck on some design issues in that game and really needed a break from it. Unfortunately, I was also struggling with my mental health after surviving an abusive relationship with a previous partner some years prior.

So, Jake suggested I take a break from working on our game and write some poetry. I used to write a lot of poetry, but hadn't been as much in recent years. He suggested it as a way to process some of the mental health issues I was having, which was a great idea, so I went for it. The poem that came out of that turned into Last Call. I liked the poem I wrote, and I wanted to design a game around it... because making games is what I love to do!

What development tools were used to build your game?

Freeman: We made Last Call using Unity, and Unity's built-in voice recognition API. We also used creative commons music composed by Rrrrrose at LoyaltyFreakMusic.com.

The game uses audio input from the player at times. Why did you want the player to speak aloud during this experience? Why was it a core of what you wanted the player to take from the experience?

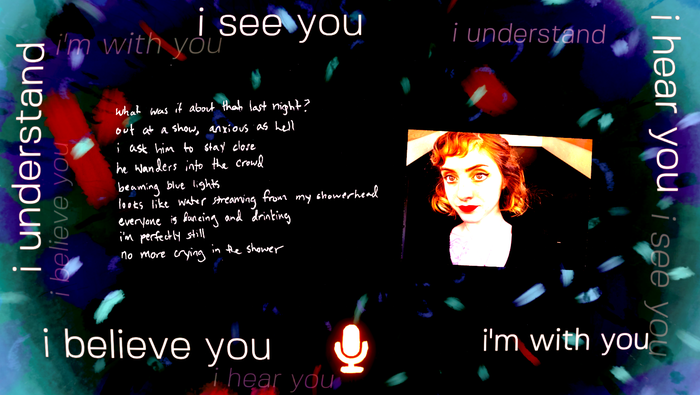

Freeman: I wanted Last Call to explore something I'd discovered after sharing my story on social media, which I had done before even writing the poem. When I talked about my experience with domestic violence on Twitter, I felt empowered and heard to a certain extent. However, seeing people like or share my story without actually responding to me did feel... weird. I wondered if those people actually read and understood my experience, or if they just wanted to share it for some other unknown reason.

So, with Last Call, I thought back to that and came up with the voice recognition mechanic. It was a way to have the player become an active listener, hearing my story and acknowledging the truth of it.

Also, I was glad to find a way to have the player experience my story without having to live it. I typically like to have players embody the main characters in games I work on, but it didn't make sense here... I don't want to ask the player to embody that kind of traumatic experience. This turned out to be a useful constraint that helped me broaden my horizons as a designer to incorporate an input I wasn't familiar with before.

How did you choose the options for what the player could speak aloud during the gameplay? Why those particular phrases?

Freeman: The phrases that the player uses to respond to my poem are based on things real people have said to me, and things that I have wanted to hear from people when I share my story with them. My primary focus was to have phrases that offered some nuance in response, but that were also things I felt comfortable asking people to say.

I wouldn't give the player a chance to deny the truth of my words, because... well, f*** that [laughs]. Victims of domestic violence are so often gaslighted and denied that I didn't want to give the player that opportunity AT ALL. Players do not get to progress if they don't agree to acknowledge the truth of the story.

However, there is of course the constraint of what our voice recognition is capable of... and thus our phrases are quite brief. I'm sure that voice recognition is capable of more complex phrases, but we didn't have the expertise or bandwidth to pour hours into that. Zero budget game lifestyle! We took the simpler route, and chose to go with brief phrases that felt right to me and that worked well with our voice recognition API.

This game is an autobiographical work from a difficult time in your life. What drew you to capture this time as in interactive experience?

Freeman: Domestic violence is a topic that is not discussed enough, given how (sadly) common it is throughout the world. It is especially uncommon to be addressed in video games in any nuanced fashion. I think games should address the range of human experience, and domestic violence is another part of that. Since I felt safe and able to do so, I wanted to share my story to both signal boost the issue and to hopefully reach some fellow survivors and help them feel seen and understood as well.

How did you decide on how to frame this story? Why the poetry and the move?

Freeman: It is difficult to write about domestic violence, because it is a situation that spans well beyond a single act of violence--it is the culmination of violence, or multiple acts of violence, within an entire relationship full of different kinds of moments. I felt strongly that I needed to depict aspects of the relationship that also did not include violence, in order to show the complexity of a human relationship that can also involve these unfortunate acts of violence.

I thought that using poetry would help me express that nuance, and that the move would frame it in a positive light; I did survive and left that relationship behind, which is extraordinary. Many people who experience domestic violence remain stuck in their situations for a myriad of reasons. I wanted to ensure that I captured the scope of my personal experience while also leaving the game on a hopeful note; I found the strength to leave that relationship, I moved out, and I survived.

What thoughts went into the visual representation of the game? The real photos, the fire/broken glass visuals on top of the boxes, the realistic items in the boxes, etc?

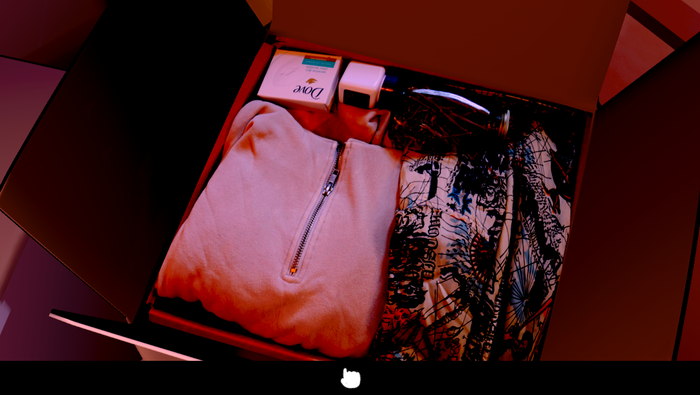

Freeman: I spent many hours arranging boxes and filling them with my things in real life... everything you see in the boxes in Last Call are really my belongings. I wanted the boxes to help give the player some context about the kind of person I was and the life I lived at the time. I wanted the space to feel full of me, and things unrelated to my abusive relationship, because I am a lot more than that.

Survivors of domestic violence are much more than their survival stories. I needed to capture that in this game. You can learn a lot about a person through their belongings... so, I curated the boxes with that in mind.

Using real photos instead of illustrations was really, at first, motivated by the constraints of our development situation: Two people with no budget trying to make a game, fast. As I mentioned before, Last Call was something we made while taking a break from our main project, so we cut a lot of corners to make it work. Jake designed the art style with that in mind. He wanted to combine these different elements in a way that made the style feel immediate and intimate, like looking through someone's sketchbook.

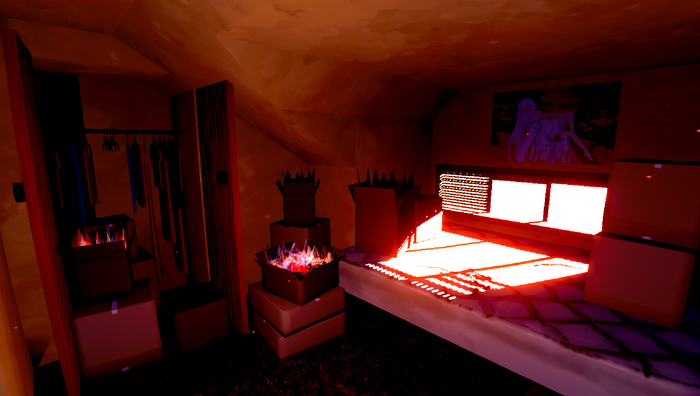

I really like how so many different textures and art styles meet to create a whole piece. The combination of real photos with surreal shadows and flames and chunky environment art all added up to something that felt appropriately chaotic. The overwhelming act of sharing the story itself is represented by the space. You look out into the dark room and see jagged flames dancing around, all your stuff is on fire, and the thought of going through it spikes your anxiety.

But as each box of memories is closed and packed, the anxiety of it all slowly dissipates. In the end, you're left in a calmer space - hope. That reflects how I felt sharing my story.

What difficulties do you face in dredging up these likely-unpleasant memories when you're working with them? How do you take care of your mental well-being when working with challenging, personal subjects?

Freeman: Last Call was definitely hard to make. Luckily, I didn't have to make it alone and had the awesome support of Jake. He was super helpful throughout the whole process, and brought clarity when I needed it. I don't usually make these personal games to deal with trauma—usually I will work on them well after having processed and dealt with the subject matter. So, this was an experiment in making something while I was still coping with the subject matter.

It did help me process the facts and feelings of my survival. Writing the poem, specifically, felt cathartic in a way. But really, that process is always ongoing (and will be different for every individual, of course). Recovering from domestic violence is a lifelong journey.

Do you feel that putting these difficult times into art has helped you with them in some way? That it will help others?

Freeman: I think I answered this through other questions, but I did want to be explicit about the fact that Last Call is not an educational game; it is a personal game. I definitely hope that it helped signal boost domestic violence as a serious issue. However, my experience of domestic violence is unique to me, and definitely doesn't represent all cases. There's plenty of journalism and research out there about domestic violence that you should look into if you feel you need to learn more about it.

I can't speak for other survivors, because domestic violence is an issue deeply rooted in race, class, gender, culture, economics... I could go on. I can only speak for my situation, and hope that any fellow survivors who played this game felt seen, or less isolated. If you or someone you know are experiencing domestic violence, you should definitely seek professional resources and help. I recommend ncadv.org/resources.

This game, an IGF 2022 finalist, is featured as part of the IGF Awards ceremony, taking place at the Game Developers Conference on Wednesday, March 23 (with a simultaneous broadcast on GDC Twitch).

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2022You May Also Like