Event Wrap Up: Vancouver International Game Summit

Gamasutra was at the recent, inaugural Vancouver International Game Summit, and reveals insight from developers such as Stubbs The Zombie creator creator Alex Seropian and Propaganda Games' Josh Holmes (Turok) in this in-depth report.

May 16, 2007

Author: by Beth A. Dillon

The first Vancouver International Game Summit took place May 3-4, 2007 at the Sheraton Wall Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia. The event, dedicated to global perspectives on developing games for the next generation of consoles, targeted an audience of programmers, artists, game designers, producers, and studio leads.

Sponsored largely by Electronic Arts and followed by Ernst & Young, Disney Interactive Studios, and Microsoft, the event was also partnered with New Media BC and the International Game Developers Association. The Casual Games Association announced a surprise industry networking party for the first night of the Summit.

Overall, the Summit’s topics addressed the current state of game industry. “What it’s really time for is to put ourselves forward as professionals. This is not a garage industry anymore, we’re an industry of professionals,” stated Douglas Tronsgard, CEO of Next Level Games, during a panel on workforce optimization headed up by International Game Developers Association’s Executive Director Jason Della Rocca.

With opening remarks were representatives from Vancouver media industry, the Executive Director of Masters of Digital Media Program at the Great Northern Way Campus, Dr. Gerri Sinclair, and Lynda Brown, the President of New Media BC.

Keynotes included the Vice President of Microsoft Canada’s Developer and Platform Group, Mark Relph, the Founder of Wideload Games, Alexander Seropian, and the Senior Vice President and Group General Manager for EA Canada, Rory Armes. Amongst its keynotes, the Summit held afternoon interactive workshops and three panel tracks: Management, Technology, and Design.

The Design Track featured David Elton (Senior Designer, EA), Sean Smillie (Designer, Action Pants), Jonathan Dowdeswell (Producer, Relic Entertainment), and Clay Jensen (Creative Director, EA Black Box) on effective pre-production. They discussed methods that can be used to visualize and test concepts before a studio spends the bulk of their title budget.

In the Management Track, Neal Clarance from Ernst & Young spoke alongside Howard Donaldson from Propaganda Games, Vlad Ceraldi from Hothead Games, and Steven Hnatiuk from Yaletown Venture Partners with insights and personal takes on how to raise capital and negotiate with various models of publishing and distribution. Each game development project has to negotiate for financing on an individual basis, the panel agreed.

Agile game development came up as a key topic for the Technology Track. Tarrnie Williams from Relic Entertainment, Dan Irish from Three Wave Software, Phillipe Kruchten from the University of British Columbia, and Steve Adolph from WSA Consulting spoke to new approaches in team structure and the experience of using agile methodology during the development cycle. The technique relates to with iterative design and current strides toward managing increasingly large development teams. However, agile development can also be applied to small development teams and steps in user-generated content, which is supported by companies such as Microsoft.

Keynote: Microsoft Canada’s Mark Relph

Mark Relph, Vice President of Microsoft Canada’s Developer and Platform Group, opened the Summit with a keynote about Microsoft’s current exploits in game industry. Although Bungie Studios (currently working on Halo 3) is often pointed to as the main game tie-in, Microsoft has taken strides in its involvement with game industry from commercial, developer, and user standpoints.

Windows Vista, the new operating system from Microsoft, includes an integrated Game Explorer with parental controls. With multichannel audio, widescreen support, and an emphasis on networking, Vista is promising to connect with the Xbox Live community of around 6 million users. Microsoft intends to make the same titles available on both platforms and eventually enable users to interact through multiplayer functions between Xbox and PC.

To expand on community growth with users, Microsoft’s XNA Game Studio Express offers opportunities for user-generated content. “Enthusiasts, students, and independents want to make games, but there are barriers like cost and the acquisition and use of tools,” said Relph. In the case of XNA, technology is the enabler—“easy to use, easy to acquire, cross platform, secure, and with a path to the professional,” Relph added.

Microsoft's XNA Creators Club gives power to the people

Community comes into play with the XNA Creators Club, which allows users to share their games on Xbox Live. “We’ll see unsigned code running on the box,” Relph pointed out.

Microsoft is making an effort to include both academia and industry in XNA. DevelopMental Tour Canada, a game workshop camp, has templates, curriculum, and source code available for anyone interested in running workshops using XNA. They intend to continue their academic progress by getting XNA integrated into college curriculum.

Looking ahead to the future, Microsoft is working on XNA Professional for studios. In addition, Microsoft is seeking out ways of using games for purposes outside of entertainment, such as dynamic in-game advertising. “We’ll have interactive advertisements through all members of the media family,” said Relph. Lastly, Microsoft Silverlight, a suite of authoring tools for the web, has possibilities for developing games targeted at the casual games market.

“This is an unbelievably exciting time for game developers,” Relph stated. The industry is “marching ahead in terms of development tools and experiences” as it continues to grow its “talent and imagination into how games are put together,” he concluded.

Keynote: Wideload Games’ Alexander Seropian

Formerly representing Microsoft, Alexander Seropian, who started out as the Founder of Bungie Studios (Halo) and has since founded Wideload Games (Stubbs the Zombie), keynoted in the afternoon.

Seropian’s talk on “The Once and Future Game Developer” began with his overarching viewpoint on independent game development in the current game industry.

“The business of game development has changed,” said Seropian. “The do-it-yourself, internal development model has become so bloated and risky that only giant publishers can afford it and they’re only willing to on a slam-dunk franchise.”

“Innovation and originality are the driving forces behind the game developer model of the future,” he continued. “It’s not outsourcing, it’s not a core-team model. It’s a new producer-driven culture that’s creatively focused, scalable, and replicable.”

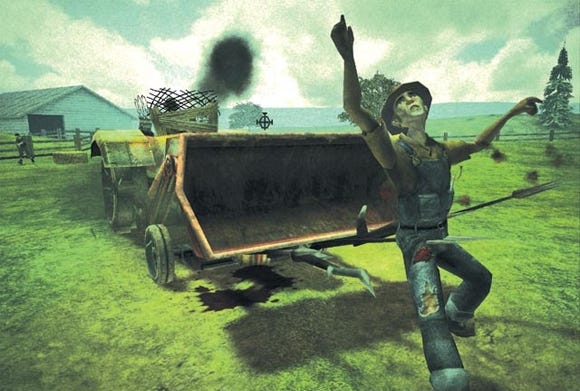

Wideload Games' Stubbs the Zombie

“These days, it seems hard to do original stuff. A lot of publishers I talk to put ‘original’ in the ‘risk’ category,” Seropian elaborated. When he was first pitching Stubbs the Zombie, he described the game to a publisher as “a zombie game where you play the zombie.”

The publisher responded that they’d look it over with the marketing team and get back to him, and when they did, they said the idea would be great—but with the player as a hero killing a bunch of zombies.

“There is a lot of opportunity in the video game business to be original and creative. At the same time, trying to achieve that goal is risky to the people who are going to invest to achieve those goals,” he continued.

The root cause of the risk, Seropian believes, is the “man power involved” in development. Even so, risks are numerous in game industry. From the market, which is hit driven, very competitive, highly subjective, and the cost of entry is high, to the development side, which requires completely new hardware platforms every 5-7 years, new engine and other technology requirements every 12-18 months, and continuous development cycles every 24 months.

On the upside, Seropian asserts, demand for game content and game developers is huge and growing. Grand Theft Auto and Halo have sold over 10 million copies each, while Rare, Red Octane, and Harmonix were each acquired for sums in the triple digit millions.

“Our industry is somewhat unique in that interested parties will fund projects without acquiring a company’s stock,” said Seropian. In any business, long term value and enormous multiples are a result of ownership, and for game developers that means owning intellectual property.

Seropian argues that internal development models just won’t work for independent developers anymore, and that development has to be under the umbrella of a big company that can afford it. At Wideload, the core team is made up of 19 people. The technical work is outsourced to contractors that the company creates long-term relationships with.

They provide their “partners” (a term Seropian prefers) with the technology and training they need to complete projects, hoping for the contractors to work on future projects as well. This allows the core team to focus primarily on the IP side of game development.

The risk may be going up in game industry, Seropian comments, and developers are facing barriers to innovate, but he believes that as game industry continues to grow, small companies will get smarter while big companies get bigger.

Different Game Development Models

But what about other game development models? “The bottom line is that you have to make new risks,” stared off Josh Holmes of Propaganda Games in his presentation about different game development models. “We have to grow our audience,” he then warned. Holmes believes that people will lose interest if the industry doesn’t break down the control barrier and look for better ways to get hits.

In the short term, Holmes offered solutions for enabling low budget development, including outsourcing, middleware engines, and third party plug-ins. In the long term, he suggests that small game companies look into higher order middleware engines, low cost development hardware, and complete content libraries and asset solutions.

“Think about changing your business model,” said Holmes. Episodic content, digital distribution, in-game advertisement, and micro-transactions are all alternate models for generating financial security.

Traditionally, Holmes explained, developers decide on a genre, research other games within that genre, and list the genre’s conventions and “must haves” to improve on the genre itself. Instead, he suggests, developers should figure out the emotional experience they want the player to have, research games across all genres that provide that experience, and then develop game mechanics to deliver that desired experience.

“Design should be collaborative, not ‘design by committee,’” Holmes argued. He emphasized having partnership across disciplines, and putting designers in the role of “shepherds,” not “autocratic visionaries.”

Design should also be iterative. “Building a new game is like building a new home—you can’t know exactly where the furniture should go until you live in it for awhile,” Holmes said. Developers should articulate the design goals and expect to make changes as they implement them.

Holmes outlined his strategies for optimizing development. First, he schedules with time built in for change and allows for reflection. Second, he fights. “Fight for what you believe in,” he emphasized. “Respectful conflict is an important part of the process.” Lastly, said Holmes, “it’s not good enough to keep doing what we know works. We have to take risks if we want to grow this art form.”

The audience was stirred up with debate over Holmes’ talk, largely because Holmes is at Propaganda, which works on IP-oriented console titles. An employee of Radical pointed out: “First and foremost with a publisher is credibility.” Without credibility, the chances of being able to take risks as a small developer are slim.

Holmes recognized the response and explained that Propaganda is working on more established titles in order to be able to take more risks in the future. In a sense, they are currently working on their own credibility.

Jason Della Rocca, the Executive Director of the International Game Developers Association, pointed out that game industry includes platforms outside of consoles, where there are many unique development models to work with different genres of games. He referenced Eric Zimmerman’s GameLab as an example of an alternative model.

Overall, there was a call for more acknowledgment of independent game development in the mix of discussions concerning consumers as creators and the shift of media to a content-oriented industry with medium crossovers, which is not only affecting Vancouver, but international industry as well.

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)