Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra is proud to be partnering with the IGDA's Preservation SIG to present features covering each of the first ten games voted into the Digital Game Canon, beginning with a detailed history of the 1961 mainframe-based shooter Spacewar, seen as arguably the first ever video game.

[Gamasutra is proud to be partnering with the IGDA's Preservation SIG to present detailed official histories of each of the first ten games voted into the Digital Game Canon. The Canon "provides a starting-point for the difficult task of preserving this history inspired by the role of that the U.S. National Film Registry has played for film culture and history", and Matteo Bittanti, Christopher Grant, Henry Lowood, Steve Meretzky, and Warren Spector revealed the inaugural honorees at GDC 2007. The first history to appear is J. Fleming's history of arguably the first ever video game, 1961 mainframe-based shooter Spacewar.]

Harvard mathematician Howard Aiken expressed the opinion in 1948 that no commercial market for computers would ever develop and that only a handful of the complex and delicate machines would be needed by the United States.

However, even as he spoke, researchers were dreaming up new ways to refine the hardware, making it faster, smaller, and more reliable. Across the nation’s universities students were ignoring the pronouncements of prophets on high, eager to get their hands on the devices, to take them apart and reassemble them in new and more interesting ways, to make them personal playgrounds for the imagination.

In 1961 a small group of friends gathered regularly at a small apartment on Hingham Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Steve “Slug” Russell, J.M. “Shag” Graetz, and Wayne Wiitanen shared a common interest in the nascent field of computing, having worked together at Harvard’s Litauer Statistical Laboratory where they ran computations on the IBM 704.

“Wayne and I were roommates and we’d constantly get together at our place. We’d go to see these awful Japanese science fiction movies, the Godzilla movies and American grade-z science fiction,” Graetz remembered.

Along with trashy movies, the group had a special fondness for the pulp fiction of E.E. “Doc” Smith. “We wondered why don’t they pick up on Smith’s novels? They’re terribly written but naturals for the movies,” Graetz said. “You have to let your mind relax a good deal in order to get with it, but he sometimes had some really compelling visual images.”

Russell and Graetz soon left Litauer for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where they would get a chance to work with the TX-0 computer installed at the university. “I wound up working for an old friend of mine, Jack Dennis,” Graetz said. “He was the faculty advisor for the Science Fiction Club and also the faculty advisor for the Model Railroad Club. And he was in charge of the Research Lab for Electronics.”

Throughout the fifties MIT was a breeding ground for computer innovation. In 1951, after eight years of development, the university unveiled Whirlwind, a breakthrough machine that was fast enough to execute tasks in real time rather than in batches. Based on Whirlwind’s design, MIT proceeded to create a smaller, faster version called the TX-0 in 1956, which used more reliable transistors rather than vacuum tubes.

Engineers Ken Olsen and Harlan Anderson left MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory in 1957 to start their own computer manufacturing business called the Digital Equipment Corporation. “Its original stated purpose was to build computer modules,” Graetz said. “The idea was to build calculating devices and research equipment. It was not formed explicitly to build a computer. That, it was felt, would frighten off investors.”

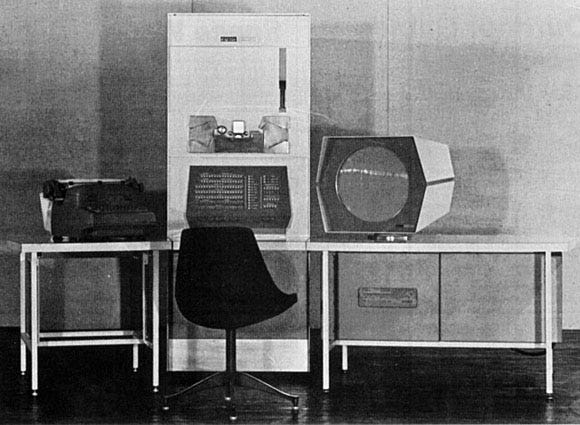

Digital’s first commercial computer was the Programmed Data Processor-1 (PDP-1). Introduced in 1960, the machine was a solid-state, general-purpose computer with the ability to make 100,000 calculations per second. It came with a number of peripheral options including a paper tape punch and reader, typewriter, and a cathode ray tube that could accept input from a light pen.

“The PDP-1 grew out of the same research that produced the TX-0 and its architecture was very similar. When Ken Olsen and Harlan Anderson and the others decided to go into business for themselves, that whole approach informed the PDP-1.” Graetz said. Priced at $120,000, only fifty of the computers were produced and in the fall of 1961 the company donated a PDP-1 system to MIT.

“One application being planned for PDP is dynamic simulation of a weapons system…” - from a DEC ad in Datamation magazine, November/December 1959.

As advanced as the TX-0 was, the new PDP-1 pointed the way forward to one-on-one interaction with computers. It was in its own way, one of the first “personal” computers. As Graetz explained, “The TX-0 filled a room with banks of power supplies.

The calculating part of it and the memory were solid state, but the power supplies were all tube amplifiers and huge racks of equipment and it took up a lot of space. The PDP-1 on the other hand, was entirely solid state and it took up about as much space as two large refrigerators. The principal difference was you could start it up yourself.”

An informal group of students, faculty, and research staff gathered in the halls of the Research Lab during the off-hours, eager to grab some time on the computers. “The PDP-1 was available pretty much at any time,” Graetz said. “Jack Dennis wrote out a schedule and people booked time on it.” Circulating through the mix were members of the Tech Model Railroad Club.

Ostensibly they were a group of gear heads devoted to model trains but they had become increasingly preoccupied with designing “hacks” or clever improvisations that created new configurations out of scavenged technology.

Russell and Graetz, among others, had plans for the machine as well. “One of the things we knew was coming was this CRT that was going to be interactive, something that was not the case with the big mainframe computers,” Graetz remembered.

“We thought how could we show off what this thing can do and it didn’t take long to realize the best way to show it off was with a game. It just seemed like a natural tendency. We were still thinking about E.E. Smith in a movie and we thought we could we do something like that. It didn’t take very long for us to figure out that the right kind of game would be a two-person game in which you tried to shoot each other out of space,” Graetz said.

“When we told Jack Dennis that we wanted to do this thing called Spacewar and could we have time on the computer he said, ‘I’ll give you a trade. If you can develop essentially the same assembly and diagnostic software, debugging software, that we had on the TX-0 for the PDP-1 over the weekend then, yeah, you can do this’,” Graetz remembered.

Enthusiastic volunteers immediately set to work creating the software tools needed to make the machine dance. “What they did was they took the pieces of what amounted to an assembly and debugging program that we used on the TX-0 and they wrote the MACRO assembler and [the] DDT [debugging program],” Graetz said.

“Having those things in hand, then we were allowed to have time on the machine to develop [Spacewar]. It started really with Slug programming the control program and then all of us pitching in to write different pieces of it and it went from there. We needed a few sub-routines that Alan Kotok got from Digital, a couple of multiplication and division sub-routines,” Graetz recalled.

Initially, Russell was slow to start work on the game and the hackers were getting impatient. In Steven Kent’s book The Ultimate History of Video Games, Russell said, “Eventually, Allen Kotok came to me and said, ‘Alright, here are the sine-cosine routines. Now what’s your excuse?’”

Spacewar began to take shape in January of 1962 with a simple program that allowed controller switches to change the direction and acceleration of a dot moving on the computer’s CRT. Within a month Russell had refined the program, creating two spaceships moving independently across the screen.

In Kent’s book, Russell further states, “They [the rockets] were rather crude cartoons. But one of them was curvy like a Buck Rogers 1930s spaceship. And the other one was very straight and long and thin like a Redstone rocket.”

Called the “Needle” and the “Wedge”, the ships were piloted by two players who faced off in a deadly arena, firing torpedoes at one another as they dodged and spun, fighting the pull of inertia as well as each other. Because it was difficult to judge the ships’ relative speed on the black screen, Russell created a random star field to fill the background.

Once the basic game was in place, the programmers began a series of hacks to modify and extend its play. Through their ad-hoc efforts, Spacewar moved beyond its origins as a demonstration program and became a fully realized game.

Originally controlled from input switches on the PDP-1’s frame, Spacewar was awkward to play, giving the person nearer to the CRT an advantage. Tech Model Railroad members quickly pieced together hand-held controllers out of spare switches, plywood, and Bakelite.

Russell’s random dot background was discarded and replaced by an accurate star field called “Expensive Planetarium”. Programmed by Peter Samson, Expensive Planetarium used star chart data to display a night sky that accurately showed the constellations, including the individual stars’ varying magnitudes.

In J.M. Graetz’s article “The Origin of Spacewar!” reprinted in Supercade by Van Burnham, Russell said, “Dan Edwards was offended by the plain spaceships, and felt that gravity should be introduced. I pleaded innocence of numerical analysis and other things, so Dan did the gravity calculations.” Introducing a strategic element to the game, Dan Edwards devised the “Heavy Star”, a burning sun in the middle of the screen whose gravity affected the motion of the ships. If ships did not maintain thrust the Heavy Star would slowly draw them down into its fire, forcing players to consider its mass when vectoring their attacks.

Introducing a strategic element to the game, Dan Edwards devised the “Heavy Star”, a burning sun in the middle of the screen whose gravity affected the motion of the ships. If ships did not maintain thrust the Heavy Star would slowly draw them down into its fire, forcing players to consider its mass when vectoring their attacks.

Finally, Graetz created the Hyperspace jump. If things were getting dicey, panicked players could hit a jump button and warp their ship out of danger, leaving a delicate photonic stress signature in their wake. However, resorting to hyperspace was a risky maneuver as players had only three chances to use it and its results were unreliable. Ships emerged from hyperspace at a random location on the screen, possibly out of harm’s way or possibly right into the Heavy Star.

By the spring of 1962, the game dreamed up under the influence of cheap sci-fi was finished.

Not long after completing Spacewar, the hackers began to drift apart, drawn by their own Heavy Stars. Wiitanen was the first to leave, called up for military duty during the Berlin Wall crisis in the fall of ‘61. Russell left for the West Coast and joined Stanford’s AI Laboratory. Graetz and Kotok went to work for Digital while Samson and Edwards moved on to MIT’s new Project MAC laboratory.

But Spacewar had a life of its own, spreading across the computer world like a benign virus. “It was the program that was run into the PDP-1 before it was shipped. It was the last thing--it was used as actually as a final test,” Graetz said. Because the PDP-1’s memory was composed of magnetic cores, small ferrite rings whose polarity indicated whether a bit was 1 or 0, the game stayed in memory even after the power was turned off. “Core memory is non-volatile and once Spacewar was working they just shut the machine down and shipped it. So when the customer set it up and turned it on the first thing they saw was Spacewar,” he explained.

Students at university computer labs embraced the game, drawn to its perfectly tuned combination of twitch and technique. Over the next decade, they would play Spacewar obsessively, holding impromptu late night tournaments. It was ported to every succeeding machine over the years with new generations of hackers adding variations and refinements to the game’s design.

One of the many students playing Spacewar in the sixties was Nolan Bushnell, future founder of Atari. First experiencing the game while studying at the University of Utah, he became reacquainted with Spacewar after moving to California in 1969. Seeing the enthusiasm of players running the game on Stanford’s computers inspired Bushnell to create a coin-op version. Working out of his home, Bushnell struggled to make the game work on a Data General 1600 minicomputer. Unable to get the economics into the black, Bushnell realized that reproducing Spacewar in hardware, rather than software, was the answer.

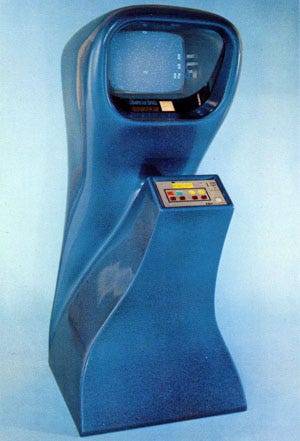

Backed by an investment from Nutting Associates, Bushnell produced a coin-operated version called Computer Space in 1971. Housed in a Dali-esque molded fiberglass cabinet, Computer Space was an ambitious failure. While the game did well on college campuses, it flopped in working-class venues where patrons had little patience for the game’s complicated controls.

Working along parallel lines, Bill Pitts and Hugh Tuck started a company called Computer Recreations, Inc. in 1971 to create their own coin-op Spacewar. Unlike Bushnell’s, their version called Galaxy Game, ran on an expensive PDP-11 minicomputer. In 1972, they built a multiplayer unit that operated in a Stanford coffee shop for seven years.

Later in the decade when the arcade scene was in full swing, Cinematronics produced another arcade version of Spacewar imaginatively called Space Wars. Developed by Larry Rosenthal in 1977, Space Wars utilized a low-cost processor combined with a black & white vector display.

Graetz remembered seeing Cinematronics version of Spacewar in the seventies. “I got really pissed off about it. I was walking by one of those arcades that were really common back then and happened to see a screen that had the Spacewar opening on it,” he said.

When programming the original game back in ’62 the creators gave little thought to its financial potential. “There was a very brief discussion, probably less than a minute, about finding some way to copyright Spacewar, but there were two things; one, nobody knew if it was copyrightable, two, it wouldn’t make any money anyway because the game platform was $120,000,” Graetz recalled.

After completing Spacewar the idea for a networked game was discussed called Console Oriented Spacewar. “It never got off the ground, partly because we had no idea how to do it, and partly because we started drifting to various other places and other parts of the country,” Graetz remembered. “But we thought if we could reprogram it for the TX-0, we had already run a communications link, a serial link between the two computers, if we could somehow reprogram it so when you’re sitting at the PDP-1 in front of the CRT and you’re sitting in front of the CRT at the TX-0 you were looking out into space and seeing the other guy.”

In Stewart Brand’s December 1972 Rolling Stone article “Spacewar - Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums”, Russell said, “One of the important things in Spacewar is the pace. It's relatively fast-paced and that makes it an interesting game. It seems to be a reasonable compromise between action - pushing buttons - and thought. Thought does help you, and there are some tactical considerations, but just plain fast reflexes also help.”

To say that Spacewar was ahead of its time is an understatement. It would be almost thirty years before its multi-player “death match” style play would become commonplace. “Using the computer as the game board, rather than as one of the participants, was brand new,” Graetz said. “This was the first time anyone had developed a game that treated the computer as the game board and you played against someone else.”

“We were just having fun. There was no inkling that computers would develop the way they would,” Graetz said. “Nobody knew what programming was. It was something you did to make a computer do things but it had no existence apart from the computer,” Graetz said. “The word ‘software’ didn’t come into existence until just about the time that we got Spacewar done. In fact, the first use of the word in a DEC catalog spelled it wrong. Even after it had a name, nobody knew what it was.”

Kent, Steven L. The Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing, 2001.

Graetz, J.M. “The Origin of Spacewar!” Creative Computing (August, 1981). Reprinted. Burnham, Van. Supercade. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2001.

Brand, Stewart. “Spacewar - Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums.” Rolling Stone (December, 1972).

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like