Disturbing players with unsettling camerawork in Paratopic

Paratopic devs Doc Bufford, Jess Harvey and Chris Brown dig into how they designed the horror game's camera cuts and aesthetic touches to confuse and disturb the player in different ways.

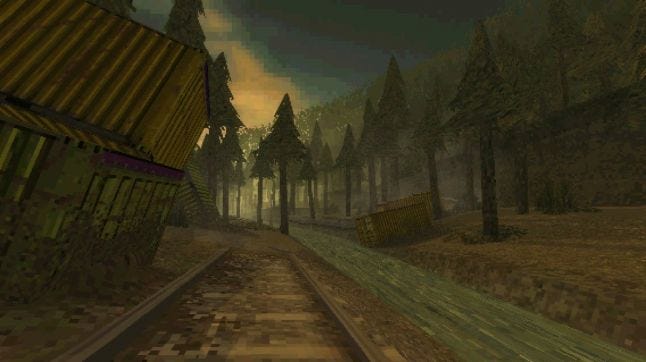

An assassin, a girl stranded in a dark forest with nothing but a camera, and a heavily armed man ensared in a fetishistic obsession with VHS tapes. These are the three playable characters in the brief lo-fi experience that is Paratopic.

The devs behind it, Doc Burford, Chris Brown and Jess Harvey, refuse to call it a "walking simulator." Tagging it as a first-person horror game doesn’t do enough justice, either.

In truth, the game relies on its aesthetic and camera cuts to confuse and disturb the player in different ways, while also telling a much bigger story than what players can see from its first-person perspective. Think of the storytelling method at play in Blendo Games’ Thirty Flights of Loving, but as a starting point for something completely unique and obscure.

In Paratopic, while there are three characters, the camera is the main protagonist of the experience. Cuts are abrupt, teleporting the player from one location to another without warning. Until later on in the game, it’s even hard to know which character the player is inhabiting between these narrative jumps.

Using the camera as a character

According to Harvey, who was mainly in charge of programming, the technical aspect is pretty straightforward: cutting to black for a given period of time or using audio bridges (sourced from either a start or target scene) served as a couple of hooks for handling shot changes.

“From a design perspective, a lot of thought and control goes in to each [cut]," she explains. "While they might seem abrupt and sudden, they’re far from random or applied haphazardly."

"While Jess and I enjoy making antagonistic mechanics, it was important to me that we avoided ever doing something that might make a player unable to continue the game."

“While Jess and I enjoy making antagonistic mechanics, it was important to me that we avoided ever doing something that might make a player unable to continue the game,” says Burford, who did most of the writing and was equally involved in the design choices.

The whole game is loaded at the start, with the exception of about two thirds of audio clips which are loaded in asynchronously. They used a header script, gaining the freedom to treat each one as an individual scene with their own lighting settings, configuration for the character motor, manage scripts and the soundtrack setup. A shot manager took care of controlling transitions, with a drag-and-drop interface for setting up the order of scenes.

“Primarily, we handle things in this manner because of resources. Implementing, testing and managing an asynchronous load while providing instantaneous transitions looked to be a moderately sizeable chunk of scope,” adds Harvey. “In another game this might be necessary, but with our visual stylings lending us a significantly lower than usual memory footprint we got away with skirting over that for the sake of taking the minimum viable product route on our tech.”

Soundtrack and audio design served as a close companion to each transition, presenting a different vibe to subtle mark every scene around the characters (nicknamed Assassin, Smuggler and Birdwatcher). Chris Brown, who worked primarily as the sound designer and composer, says that the game's transitions succeed because they cut shots off mid-sentence. In Paratopic’s first scene, the player is interrogated by a police officer. As soon as the scene begins to “end” and the person is heading towards his office, the team cut right away to interrupt a natural closing point that someone would expected.

“We effectively put that space on ‘pause’ and run off somewhere else, then we return to it much later on," says Chris. "In situations where we do this, I tried to pick up the audio as neatly as possible from where it left off."

In the diner scene, using the Assassin, the synths move slowly to provide a baseline for the rest of the music within the same space. “When we cut the player perspective to Smuggler, we also crosscut the audio tracks at the same timecode. This new piece has the same base elements as the first, but now has a slightly more aggressive warble and much more movement,” Chris explains. “The discordant elements especially are supposed to sell the thinly veiled omnipresent threat which runs throughout Smuggler’s story, also conveyed elsewhere with drones in the bass range.”

Creating a 'refracted reality'

Another strong element in Paratopic is present in its most disturbing moments. In the mentioned diner scene (which starts at roughly 4:40 in the embedded Let's Play video above), the player establishes a dialogue with a person whose face seems to glitch. To make it even worse, the camera takes the player closer to the face, until it becomes the only thing you see on screen. At the end, the angle ends up being fixed at his chin, following every movement.

“We had a number of camera mounts that we jump to, with the final one attached to the NPC’s armature. For the shifting face, the armature has an additional bone that controls the UV offset of the face material," says Harvey. "Within the creative process, I think it came in a day or two before we locked everything down to just QA."

In one of its many iterations, the scene had the player strong-armed into smuggling the tapes during a weird poker game. The character owed the man money and he would give the player a second chance through this card contest. By inevitably losing the mini-game, they would end up owing an even greater amount, being forced to do the job.

“In the end, we ran out of time and had to go somewhere simpler, which begged the thought of ‘what if the card game did happen, but we don’t play it because we’re viewing this through a sort of… refractive lens of memory?’" Harvey continues. "This streamlined down to just a refractive reality and thus we arrived at the ‘glitchy’ effect.”

When Burford first conceived the game, it was composed as separate, unrelated vignettes filled with moments that wouldn’. This included talking to a giant cowboy who could no longer move in the middle of the night, for example.

As the development progressed, Burford backed off from the technical side to focus on the presentation, finding the right balance to showcase that the scenes had a linear order to them. The writing process consisted on creating bits of dialogue that would indicate to the player when these events took place. For instance, there’s a line about being an outdoorswoman that is meant to reference the game’s final scene, something that might not be apparent until doing a second playthrough.

“We wanted the player to feel a certain way. So a lot of it was just going 'okay, how do these scenes contrast with each other?' or thinking about the build up," adds Burford "I really loved Jess’ idea to make the player wait forever in the elevator room, then immediately teleport upstairs."

The team worked to ensure that all these fractured vignettes would come together to make something that felt holistic and integrated, even if it doesn’t look that way at first glance. But even with its off-kilter atmosphere and aesthetic, Harvey admits the team always intended to keep Paratopic in a very traditional narrative arc.

“Yes, we stretch the definition of that about as far as it can go before breaking," she admits. "But it is still anchored in an exploration of formal structure.”

In the end, it's the ways in which the team tried to stretch what a first-person game can be -- through camera cuts, character swaps, and unsettlingly mobile face textures -- that make Paratopic something worth looking at if you're at all interested in game design.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)