Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How do you design a triple-A, next-generation cinematic gaming experience based on someone else's ideas? Gamasutra talks to High Moon Studios VP Paul O'Connor about The Bourne Conspiracy and crafting smart adaptations.

A great number of studios develop games based on movie licenses. For the most part, the constraints on these projects make them difficult proposition. High Moon Studios -- creators of the ambitious, if flawed, Darkwatch -- were founded on the promise of developing triple-A original IP.

The studio has been acquired by Vivendi, and is currently working on a game based on Robert Ludlum's spy character Jason Bourne - as recently showcased in a series of popular action movies starring Matt Damon.

This opens the question -- how do you design a triple-A, next-generation cinematic gaming experience based on someone else's ideas? VP and design director Paul O'Connor answers that question, joined by Meelad Sadat, the studio's director of business relations.

I am really curious about how you handled the license with The Bourne Conspiracy, because you and I both know the predominant perception of licensed games.

Paul O'Connor: It's entirely deserved.

There was quite a lot of stuff when Darkwatch was coming out about how your studio was geared toward coming up with exciting new IP. This is sort of an about-face in certain ways, isn't it?

PO: Yeah, what happened? Why aren't we doing original IP? Well, we're still doing original IP, and I'm going to be talking about that stuff. The thing about Bourne... is that I've worked on licensed properties in the past. We wouldn't have taken it at High Moon if we didn't think we could learn from it, and if it wasn't something we thought we could do and do well.

Speaking for the development staff, I was on the game from the very beginning. I was co-creator on Darkwatch. I love Darkwatch. That's why we founded the studio, was to make original properties. We treated Bourne like an original property.

By that, I mean that we found a way... I've worked on original properties in the past where all the things that you know about are happening. Fixed end date, no cooperation from the studio, a serious set of restrictions in terms of what you can and can't do with the content, and, "We have to turn this thing in nine months. Just get it out there. We'll get sixty, and we'll sell a few when it's done."

We didn't approach the product in this way. We looked at it as an opportunity to create a new property that fits into that Ludlum world. When you're doing a virtual property, you have to define the guardrails for yourself -- what that world, character, and space is going to be about. When you're doing a licensed property, the guardrails are established for you, but there's still a lot of space inside to innovate.

The way we look at it -- and I'm going to steal Meelad's thunder, because he's probably going to give you this analogy -- is we figure that there's three shelves in the Ludlum library. On the top shelf, you have all these books, and if you look on the other shelf, you have movies, and we like to think that there's going to be a third shelf full of video games.

That's kind of how we kept our creators engaged, by telling them that they weren't just doing an interactive version of somebody else's movie, or somebody else's vision.

Instead, they were handed the character bible and a world -- a self-consistent, interesting world for the characters and adventure -- and now we're going to tell stories interactively inside that space. In that sense, it wasn't much different from what we did on Darkwatch. We just had the bible on hand, instead of making it ourselves.

So it's not really tied direction into one of the particular films in the property?

PO: It is, and it isn't. We deliberately chose the The Bourne Conspiracy, which wasn't hooked up to any of the movie titles. We do use events from the first movie -- The Bourne Identity -- as touchstones in our game, so signature moments from the film, like the chase through the embassy, are in the game, and you can experience them.

But when we chose to expand the process a little bit, we went out to New York and met with Tony Gilroy a couple of times. He was the screenwriter on the three pictures, and he's got Oscar love now, which is good.

Tony, after laying down the DNA for the character and the world and what made it special, working with him, we realized we'd obviously need more action in this game, because having a game about a guy with a tortured conscience staring out the window isn't going to be much fun.

So what do we do? What we hit on was the idea of using these flashback missions, episodes and points past to flesh out the action quotient of the game. So one of the levels that he's going to run you through here is based on the embassy escape, which is a signature moment from the film. It's going to be familiar.

But another level we're going to show you is an assassination mission from points past. It doesn't have any connection to film or literature at all. It's an original work. So we got a chance to have our cake and eat it too, to do both film-inspired stuff and original stuff.

Speaking of the character's conscience, during the demo it was mentioned that Bourne's conscience will cause the character to disarm an enemy but not kill them. How does that work in the context of the game?

PO: It's contextual in terms of takedowns. What happens -- as he will explain later on -- is that Bourne will disarm somebody, he'll use the weapon briefly if it's a hand-to-hand weapon, and he'll drop it. Or if it's a gun, in this case, he actually ejects the bullet cartridge and drops it on the ground.

So it's built into the gameplay automatically.

PO: Mm-hmm.

I guess what I'm curious about is taking these concepts from the character development and then translating them into practical, cinematic gameplay elements. How do you go into doing something like that?

PO: It was a delicate dance, let me tell you. One of the things that Tony laid down for us about the Bourne DNA was he said, "Don't violate the emotional truth of the film." So what do you mean by that? Well, for Tony, in the screenplay, Marie, played by Franka Potente, is the viewpoint character.

She's the audience surrogate in this scene. And he specifically told us not to do anything in gameplay that would change Marie's perspective on Bourne. Once we had that hook, it was a little easier to understand where we could and could not go with the character.

So for instance, in the film, when Bourne fights Castel in the Paris apartment, Marie sees him as a killer for the first time. She sees that he's extraordinary. Tony told us that when Marie sees Bourne fighting in that apartment for the first time against a guy, where he jams the pen in his hand and the guy goes out the window, Marie's sick.

She's going down the stairs, and she's throwing up, because she's so terrified of this violence that's come into her life. That's only emotionally valid if that's the first time that she's seen Bourne behave this way. Up until then, he's been this charming stranger who's kind of cute. He's got a lot of money, and maybe something's happening here. Now it's, "Who is this guy?" So that threw out one act in my game design.

He told me that when I went to New York. It was like, "I got all this stuff! There's a scene between Zurich and Paris, and they're in a car, they're being chased by the police, they're going to have thugs and helicopters and all this kind of crazy stuff."

But when Tony said, "No, you can't change Marie's perception of Bourne," that's when I understood what the task was in the design, because how on earth are we going to get this action in the game without violating the emotional beats of the story?

So I guess they're kind of guardrails, right? If I was building this as Darkwatch or something, I could wave a wand and say, "Well, I can change the character so that she thinks whatever she wants." It's a different kind of creativity. We took that kind of approach and tried to say, "All right, that's what we're hooking up to."

So what are we hooking up to with the character? Well, the character has some emotional truths about him in that he's not a killer. We see that in the second film. The climax of the second film is that he apologizes. That's the emotional climax of the film. He tracks down the daughter of somebody he assassinated in his prior life as a killer, and says, "I can't bring your parents back, but I'm sorry." That's what's going on inside the character's head.

So how do I do that, and have a game that's action-oriented, where I shoot people and beat the hell out of them? Which is what all the fans want. So understanding those guardrails is where we came to... we'll do action scenes from Bourne's past -- the flashback missions -- because we know from the movies that he has this firestorm in his head all the time with his memories.

"Who am I? What have I done?" We'll let you experience those directly, where he is a little more remorseless, and he's a $30 million functioning weapon at that point, as opposed to a malfunctioning one. And then that will allow the players to get their anger and angst out, and do all the action things that they wanted to do.

And then in the contemporary scenes, we'll do a follow-up to the film. And we'll nerf things a little bit to ensure that you can't shoot old ladies in the street, because that's not what the character would do.

This is going way off the rails, and I don't know if this is of interest or not, but we worked on the first Oddworld games five or six years ago. And one of the things that Lorne was always struggling with our character Abe was that he was this very passive character. He would run and jump and hide and be weak and all the rest of these things.

But players also had this desire for violence and to blow things up. We're not going to have this schlub everyman hero and also have this action. We were developing this game in parallel -- this idea where Abe would fall asleep and have these nightmares where he would tote a gun around and kill lots of people. It was a connect-the-dots to say, "Oh, well I can possess people, and I can go off and kill them." So we found a way to keep that character, but still pay off the action.

That's what we tried to do with Bourne. Keep the character, and keep his conscience in place, but still pay off the action by showing the man who was. And for the action in the contemporary sense, make sure it's contextualized and it always makes sense.

So another thing was in the second film I think. It's something that the Joan Allen character said. She says, "Bourne doesn't do random. There's always an objective." We tried to build that in different missions so that you don't have a character that's wandering around an open world and beating up shopkeepers and that kind of thing.

He's always going in a given direction. We kind of did a flip in the restrictions of the character, and tried to put the player in that space, and helped make certain decisions for the player that would help him get smart and be like Bourne, and also drive the action.

I'm actually really interested in this cinematic technique you're using. The game starts with a mini-cutscene of a fight, and then you actually are fighting, instantly. Working on these next-generation cinematic techniques, how do these come about, and how do you keep them functional, from a gameplay perspective?

PO: Yeah, if we were doing a postmortem on this project, that would be your angle, I think, is what's going on under the hood to make this real-time cinemagraphic engine run with cuts? I mean, we talked a lot in other demos about how rapidly your brain adjusts to all these camera cuts.

But we're hard-wired to accept these camera cuts. That visual action vocabulary is part of who we are now, because of all the film and television we watch. We just embrace it. We just go with it. And the designers in the room are all like, "Ah, we can't do that. Take away control, and the player's going to get disoriented."

So that it does work is really pretty amazing, and like anything that's really simple, it's really hard to do. I think you'd want to talk to our cinema guys and our engineers. I can give you layman's terms, but I think there's some real interesting lessons that might be of interest to [your audience].

Meelad Sadat: It's a good topic. Talking about when we first started showing the game, there's things that I'd never seen done in an action game before, like real-time camera edits within the action. In takedowns -- I'll point it out to you -- there's actual cuts away from the action to frame it differently. So anywhere from two to five cuts as you're taking somebody down, to give you angles.

PO: And that's all live. The camera's pretty smart. We get the occasional boner where you fight the wall or something, but for the most part, it's doing a good job.

The other question I have is that the series of movies are sort of pitched as the thinking man's action movie.

PO: The thinking man's James Bond.

Right. Obviously that's sort of... I don't know how to phrase it. It's a lingering question right now with games. Yeah, sure, we want lots of violence and some sex and stuff, but it's not necessarily maturity that's commensurate with real, thought-provoking film. What do you think about bringing that kind of sensibility into games right now?

PO: We've had to do it, but obviously with different forms. We have to concentrate on what's actionable. We tried to retain those emotional beats to the story, and tried to restrict the character behavior so that they will behave in an intelligent fashion.

I'm not sure we got all the way there, as much as we would like. I think the character could be a little smarter with his interaction with the environment. But it was something that was in our minds.

It's difficult. When you go and see a James Bond movie... I'll speak of what I think makes the character smart, and maybe you can tell me how to do it in this game. I'll tell you what we ended up doing. When you go and see a James Bond movie, the audience is ahead of the character, generally, because they have a wonderful setup scene at the beginning of the movie where Bond goes to talk to Q and Q says, "Here's all the treasures you're doing to take on this adventure."

You kind of forget about them, but in the back of our head, "When's the watch coming out? When's he going to use the aftershave kit?" So when he breaks the stuff out, it's kind of a familiar surprise. But the audience is ahead of him, because they know what the solution will be to the problem. They've forgotten about it, but it's familiar when they see it.

In Bourne, it's reverse. The audience is always behind Bourne. Bourne is always thinking two or three levels ahead. He's going to deliberately let himself get captured by holding his hands up, and when somebody gets close to him, he executes a quick reversal and kicks people out.

Or he lets himself be captured and brought into a room so he can get somebody's cell phone and clone it. He's always a couple steps ahead of what he's doing. There's no way the audience can anticipate what's going to happen, but it's so fast and with such assurance, he seems really smart.

So how do we do that with the player? For a long time, we wandered down these alleys, like, "Okay, we'll let the player do a mission plant. We'll sneak into the areas ahead of time, plant weapons, case the joint, and figure out where everything is." We just thought we'd end up with a watered-down version of Splinter Cell. It wouldn't be as good or as interesting as that game. So we decided to go up-tempo with the action.

How we tried to preserve the character's thoughtfulness and his improvisation is in the contextual interactions with the environment. What'll happen is when Bourne is fighting, he executes these takedown moves, and depending on what's in the environment, you get different outcomes. The controls are simple, but the outcomes are a surprising and complex.

That's where he's going to grab a pen off a table and grab it into somebody's hand, or he's going to use a fire extinguisher to take somebody out, or he's going to fire his gun and flush enemies from cover. So the player has to initiate those things, but the results can be a bit of a surprise, and it allows the player to express himself with style.

We tried to do the same thing with the Oddworld games. Give the player a lot of tools so they can express themselves in terms of how they want to handle a puzzle or a situation, and hopefully delight people in the room watching.

That's something you see games experiment with lately. The obvious example that reawakened it is God of War, with the contextual action, which everybody started reincorporated as soon as God of War brought it back. God of War didn't come up with it, but...

PO: It's Dragon's Lair.

Dragon's Lair and other games. Shenmue, definitely. But they made it chic. And I guess it's because I recently played Devil May Cry 4, but the way they did it is... Devil May Cry used to have sword and gun attacks, and the new one has sword, gun, and a throwing arm. Every throw move is contextually sensitive to the enemy that it's used against.

It's cinematic, in the sense that it has a whole new set of animations that are done just for each enemy type. It's not like the sword, where it's the same slash you see no matter what you're fighting. But with the throw in DMC4, it's like you're fighting this one enemy, and you pick it up and spin it around and chuck it across the room or whatever. That's a big problem that's being worked on right now, is how to bring that film-like, cinematic quality and retain interactivity.

PO: And aware of whether you're playing, or was the game playing you.

Right.

PO: When I play Call of Duty 4, for instance. Great game. Love it. But it's a ride zone. I'm on a rail, and basically I'm going from one spot to another, and the events are triggering based on my penetration of the camera value, rather than the outcome of my mission planning. I don't care, because it's so brilliantly executed.

There's a line where I as a player... it's the willing suspension of disbelief and control that I'm willing to seek in a game if it sufficiently satisfies my need for action, excitement, and surprise. It wears a little thin when I get the same sequence four or five times in a row. We see that a lot. But I think we've got to give credit to the audience. We're never going to fool them into thinking they're not playing a video game.

A lot of times with these cinematic games, "We're going to take the HUD away, and you're never going to know you're not playing a game." I think that's crazy. It's a separate form, and you embrace the aspects of it that allow you to make the game fun. That's why we have those quick action moments.

If we were going to do something that's totally cinematic, you wouldn't allow that to be in the space. I think we embraced those things because it worked, but at the same time, I don't think there's anything wrong with surprising the player by taking away their control of the situation a little bit. As long as the player's buying off on it, then yeah, we'll do that.

That context thing? Yeah, I'm on board. But yeah, you're right, we're walking a razor's edge. With Bourne, we also were demanded to make this a very accessible and broad market game. Obviously, it's a hugely successful film franchise, and the company is hoping it can be a mass-market success.

That also dictated the way we used the controls and how deep we wanted to go on some of the control combinations. But I don't think the answer lies in increasingly complex control schemes and really stupid learning curves. I also don't want to have a game that's an inch deep and a mile wide. I think that a game needs to trust the player a little more than we have in the past.

There's been a fear that the players are not going to get it, or they're going to punch out after 15 minutes, or they're going to rent it and never buy it if we can't give them this incredibly deep experience right from the get-go. I give players more credit than that. They want to be entertained.

What I find interesting when I played the demo is that, as you run through the level, I just about saw the guys who were sliding in on the edges of the screen or around a corner. You can really tell without too much difficulty "don't go that way," without really stopping and looking. How do you work on those visual cues?

PO: Hundreds of hours? (laughs) Nights and weekends, loss, divorces? There's some audio cues there too. A lot spilled into the art. There's light sources pulling you. The camera is also suggestion a direction for you to go. There's a lot of little magic tricks that are happening.

It would've been a perfectly valid approach with this game to have all those takedowns be unlocked by specific control combinations. X plus Y plus left bumper plus adrenaline and swirling my thumb on the left control stick.

Plenty of games have done it that way, but we thought, "Am I going to feel smarter when I do that, or am I going to feel like I'm a dolt who can't be as good as the character in the game?" By simplifying those controls, but making the outcome of the input complex, we hope to make you feel like Jason Bourne.

I can't say I'm speaking for anyone but myself, because who knows what people want, but I'm looking for elegance now, not memorizing combo strings.

PO: We want this effortlessness. I want to be this $30 million weapon, and I don't want to go to training school to get there. I want to pick up the controls and be this guy in a short period of time. That's why we took that approach. That deliberately formed the way we built the camera.

The game reminds me in a vague sort of way of Sega's Yakuza game, if you've ever seen it. That had context-sensitive takedowns in a contemporary setting. That game was really underappreciated for some of the stuff it did, so it's worth looking at.

PO: I think we looked at that one. We looked at... what was the first Jet Li game, Rise to Honor?

MS: Yeah.

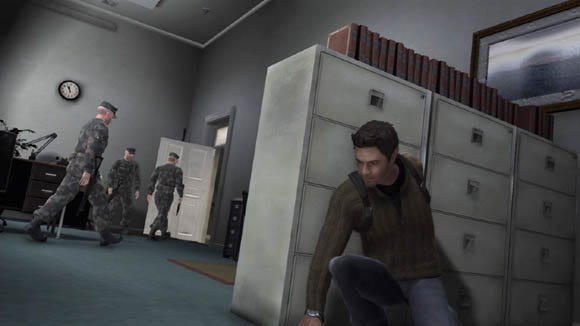

PO: And tried to do some of the same things. We looked at Power Stone and old-school brawlers and that stuff. But again, it was formed by the property. It didn't always have fight scenes in rooms like this [embassy office], these ordinary places that are loaded up with everyday objects that are then used in a surprising ways.

We wouldn't have these environments. But part of what makes Bourne so authentic is that Bourne isn't fighting a bald guy with a cap inside a hollowed-out volcano. He's fighting for the fate of the world in these enormously mundane locations. It's the juxtaposition between the extraordinary violence of his world and the everyday world that makes it seem authentic.

This game is on the 360 and PS3. Do you have anything to say about the development process on doing multiplatform games?

PO: We needed a lot of support on Unreal to make it run on the PS3. We got caught in the same crunch as everybody else when they finalized Gears, so that definitely slowed down the PS3 support at the time. But, that being said, the guys have done extraordinary work with the PS3, and it's just about ready to pipeline.

Then again, there's controversy relating to that.

PO: Yeah. Well, it's been what, just a few titles that have shipped on PS3 from Unreal so far? It's not... I don't want to badmouth Unreal. It's an awesome toolset.

We wouldn't be where we were if not for Unreal, and their support has been as good as it could be for a company that's had its attention so divided between supporting the developer community and making their own game. But we had to roll a lot of our own stuff on the PS3.

I think that's a common experience. When looking at the Bourne in your game, that's obviously not Matt Damon.

PO: This is not Matt Damon. This is not the Damon you're looking for.

In a certain sense, I'm sure you can argue it multiple ways. The books aren't Matt Damon. They're the original character.

PO: This is definitely different from the movie character as well. We optimistically hope that we're starting a franchise here, and Mr. Damon's given any number of signals that he's done with Bourne.

They may be able to pay him enough to come back for a fourth picture, but at this point... we're hoping to do several of these games going forward, and it does make sense for us to have our own identity in that main character. But you know, a lot of those decisions are made upstream from us.

Bourne could become like Bond, go indefinitely.

Well, I know in the last script, the original third act is a little different, to set up another character who was going to pop out of the franchise. The producers are thinking about it too. It's the guy on the rooftops.

MS: At the very end.

PO: Yeah. He had a much larger role in the original script.

You know what movie game I really liked that I thought delivered a movielike experience that was actually good? It was King Kong. That was a really good game.

MS: That was one of the games that tried no-HUD.

PO: I think it was a little too clever in that regard.

I turned the HUD on, actually. I turned the ammo HUD on. I thought that was really silly, instead of pressing the button to tell yourself how many bullets you have. "Five bullets left!"

PO: That's maybe the exception that proves the rule. I thought that was a cinematic game, and I thought it did depart from the story in really interesting ways, and there was a lot to like about it. But I thought they took the HUD away just to take the HUD away. I didn't see where...

At least it was an option that you could turn back on. I always wanted it on.

PO: But it was a conceit. I think it was a boardroom choice. I don't think it was a game design choice. I think it was, "It won't look like a movie. Take that away."

I don't have any insight to the development of the game, but I bet you a dollar that's what happened. We played that quite a lot, because I was on the review board for the AIAS and needed that for the story award. Because it did take some steps into a new space.

CN: I thought it was really... I really did like it from a story perspective. [Playing Bourne while talking.] And your health can come back, as long as you get to a safe spot.

PO: Yeah, to catch a breather. Kind of stealing a Call of Duty trick there. In the original design, we were thinking more in terms of open worlds and persistent wounds for Bourne, but it slowed the pace too much.

You'd be hunting around for medical packs. It made the level design a little easier, because you'd have reasons to go to all the nooks and crannies, but it didn't feel right.

This is just my personal "I'm not a game designer. I just like games and I'm kind of bored right now," voice, but I don't see any reasons to stick to conventions, if you decide... why have a health meter that works the way health meters have worked for the last 20 years, if you're just going to find something that works differently for you?

MS: We experimented with using facial deformation, for example.

PO: We tried a lot of different things. I used to write comic books in my secret past. When you write a comic book, you get things that come with it being a comic book. People are going to accept that a superhero flies around in long underwear. They're going to accept that Clark Kent can put his glasses on and nobody's going to recognize him as Superman.

They're going to accept those things until you shine a light on it and say, "This is ridiculous." And you can do that, too, if you're a really good writer. If you're Alan Moore, you can do it. You can deconstruct a superhero story and it's awesome.

But you attack those idioms and blow up those conventions at your peril. You better be damn sure that you can replace those with something that's better or at least as good as what you're destroying.

It's the same thing with a video game. Players come into a video game, and they assume that they have a limited resource that equates to health, lives, or time, and they understand that it's going to be decrementing under a certain circumstance.

They have to get through certain hoops, there's going to be certain reset points... those things, they all accept. What happens sometimes in a cinematic game that attempts to break the paradigm is they throw those things out, but they don't replace them with anything. You just end up being disoriented.

It's like the HUD discussion with King Kong. Why did they throw it out? What would they get from that, other than a screenshot that says, "I got no HUD?"

You've got to look at those things really carefully, and if you can declaw one or two of them... how many of those little rods can you pull out before the Jenga tower falls down? Because they all support each other in ways you may not recognize, and you're saying, "I'll be different! I'll take this thing out."

That's why I think we can embrace certain things and eschew other things, and if we move fast enough and deliver it well enough against the things we embrace, that's where I trust the player.

That's where I trust the player's going to look at it and say, "You know, I'm not going to ding them because it doesn't have a Tekken level of depth in the fighting commands. That's not what they were aiming for. But look what they did do. It's got all this depth, but it's triggered by this control scheme. And it's fun."

Another example of where that sort of went wrong is... and this game is pretty old now, so I'm not harping on it, but The Getaway was the big groundbreaking title as, "Let's make it as realistic and..."

MS: And you're leaning against a cabinet.

Leaning against a cabinet and then the blood will dry on your shirt. The thing that is even sillier to me, almost, was the fact that when you're in the car, you'd know where to go because the turn signal would turn itself on for you. I thought that was kind of funny, more than anything. I think when they decided to do this, they were definitely going at it from artistic intentions, but it almost was sort of an anti-proof of concept or something.

PO: You've got to be willing to make hamburger out of the sacred cows, too. You can sit with the design session. On the whiteboards, they've got all this stuff. But when you're playing it and it's not working, maybe it's time to change your objective a little bit.

You know, video games aren't reality. Duh. But fiction isn't reality, either. The people talk in novels is not the way they talk to each other in person. There's concision. There's summary. There's things that drive conversations to climaxes and character transformation, and where you get into a scene and out of a scene. They're different than life, so why should video games be held to a different standard when they're trying to show us action?

We have this marvelous legacy of cinematic action that goes back to D.W. Griffith, so why would you try to go against that grammar that's ingrained in everyone's head? For us, it was top-down.

We looked at the director on the second two pictures, and we looked at the way he framed his action. His philosophy was basically, "There's a cameraman in the room with you in all the fights, so when Bourne gets hit, he flinches."

He's pulling the camera back. You can see this in the second film, where Bourne's driving, and a car's coming in and is going to smash. He's looking ahead and can't see the car coming this way, and the camera flinches back, even thought Bourne hasn't seen it because we're the cameraman in the passenger seat going, "Holy shit!" and he gets hit and spun around.

So we grabbed all those elements and built them into our camera system so that it feels like the film. But those huge fights make that stuff happen, because that's normally the way you do a video game.

We're breaking one of the idioms of a video game, which is a reliable camera that the player can control. You can't do that unless you give them a better experience, or at least a different experience that holds together.

Well, to look at it from a film perspective. A camera in a video game is usually a crane. It's not a handheld camera. But people use different kinds of cameras in film for cinematic reasons.

PO: Well, cameras are used prominently in places in Gears of War. When they're sprinting to cover, the camera gets kind of low. I feel like I'm watching Full Metal Jacket or something. It's handheld. It's like "great!"

But that only works because the cover system is so well-implemented and because Gears isn't full of a lot of guys who are sniping you from long distance. The engagement plane is pretty close between you and the enemy, so I can leapfrog to cover and fight guys, as opposed to run out in the open and get shot down.

Then it wouldn't work, because I'd say, "My camera's gotten into a tunnel and I can't see the enemies. It's not fair." But they've given you a break, and they're going to lay off of you, because all of the energy is going to come out of the camera setup for the running.

So we tried to do the same thing. We'll move the camera around, but it's during the fights... I've done the input, and now I'm getting response. If the camera was jumping around on you when you were trying to line up your enemy or do a disarm move or whatever, you'd hate it. You'd pitch the controller in a second, because it wouldn't be playing fair.

The first time I really noticed [handheld camera] it was in Dr. Strangelove. The cockpit sequences in Dr. Strangelove, where they're attacking the airbase, were so authentic that I thought, "This has got to be combat footage. There's no way that they shot this." And that's where Spielberg went back to for Private Ryan.

MS: A key part of the shooting is that we have a cover system. We used Unreal 3, as you know, so our guys had the luxury of picking and choosing the parts of the Gears of War cover system that we thought that fits the Bourne shooting experience.

Because you get the whole Gears source code, don't you, when you get the Unreal license?

PO: We got the whole level layout, too. That was a cold bath for my guys when they saw how they built the Gears of War levels. They look a lot more complex than they are. They're brilliantly executed in that regard.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like