Deep Dive: A holistic approach to emotional storytelling in Roki

For Polygon Treehouse, holistic storytelling is about leveraging the full range of story tools they have at their fingertips to elevate and maximize the impact of a game’s interactive story.

August 30, 2021

Author: by Alex Kanaris-Sotiriou, Polygon Treehouse

Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with a goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Who: My name is Alex and I’m the co-founder & lead developer at Polygon Treehouse, a teeny-tiny indie studio founded in Cambridge in 2017 (although we recently upped sticks to move to Dundee). We’re ex-Playstation Art Directors who decided to flex our storytelling muscles to create the modern adventure game Röki which was nominated for The Game Awards and two BAFTA Game Awards (which we’re still pinching ourselves about). It’s been praised for its signature stylized art style and the impact of its interactive emotional storytelling, which is handy, as that’s what this article will be prodding with a curious stick.

What & Why:

Storytelling is not just the Script

Today we’re going to talk to you about ‘Holistic Storytelling’. This is our approach and ethos to crafting narrative games. In short, it’s about leveraging the full range of story tools we have at our fingertips to elevate and maximize the impact of a game’s interactive story. It’s not just about the script; The cinematography, animation, music, sound design, UI, and gameplay design itself each offer opportunities to crank up a game’s narrative and cumulative emotional punch to 11, from a limp slap to a teeth-rattling wallop. We’ll step through a few examples in this article.

Disclaimer time. This is how we like to approach our craft. It works for us. That’s not to say it’s the only way to approach things. It most certainly isn’t. Each team will find the best fit for them. This is ours.

Storytelling via gameplay

In visual storytelling the adage of ‘show’ rather than ‘tell’ is often touted. However with video games we can do better than that.

Games are an interactive medium and have the capacity to take this a step further. Rather than being possibly spoon-fed story soup, the player becomes an active agent driving the story forward. They are the agent of change.

The real magic begins when the gameplay design itself carries narrative weight rather than just being the very cool ‘filler’ in a story sandwich. Think of the act of climbing the mountain in Celeste. The gameplay itself has meaning, being intrinsically linked to the player character's internal ‘mountain’ they are trying to conquer.

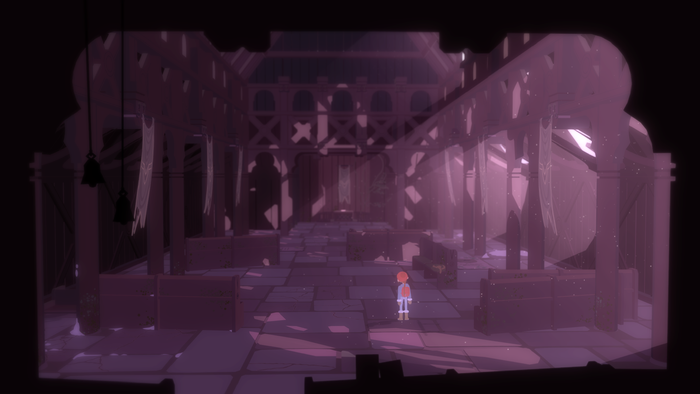

We leveraged gameplay-as-a-narrative-device throughout Röki in a number of ways, but the most prominent example is in the final section of the game (spoiler alert, you have been warned). In our game’s climactic act the gameplay switches to have two player characters, our hero Tove is joined by her estranged father Henrik. You swap back and forth between them to progress through a long-forgotten castle, each in a different plane of reality, so close, yet so far apart. The gameplay here adds weight to reforging of their broken relationship, as they co-operate and become increasingly aware of the other's presence by their (and your) action. Ultimately it’s about a desire to tell the story in gameplay over cutscenes. As devs, we think there is real power here.

Cinematography is not just for cutscenes

The camera and its narrative potency are often overlooked in video games. This is understandable as they have a critical role in making sure the player can easily read the game world, but there is still more we can do with them outside of clarity of space. We’re all used to the crushing of a camera’s focal length to drive home the impact of a speed boost or sprint in action games, but in-game cinematography can be used to more nuanced narrative ends.

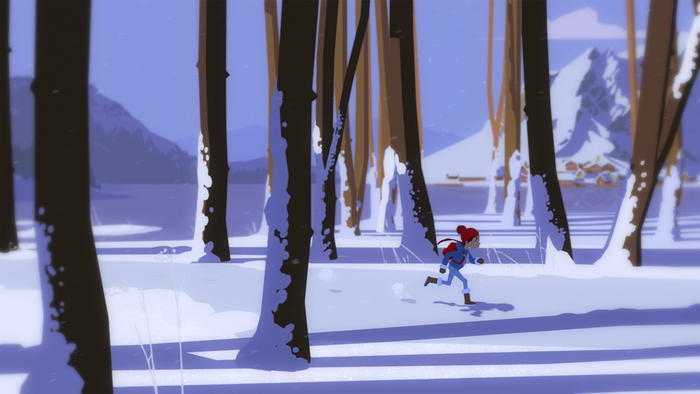

For example, in Röki the player spends the game exploring the ancient wilderness of the deep forest. As a narrative rule we decided to nestle the camera in the foreground or our scenes; amongst the undergrowth, nestled amongst mossy rocks, peering out from behind crumbling walls. The cameras were also fixed in space but would turn to watch the player as they explored the game world, like the reverse of a creepy painting whose eyes follow you around a room.

This was to give the subtle impression of being watched, an unspoken underlying threat. This world was dangerous, tread carefully.

Emotion Engine

The written word can carry a great deal of power but can be supercharged when paired with a human voice. Utilizing VO (voice-over) further realizes your characters and gives extra texture, nuance, and a human connection to your written script.

Now, working with voice actors can be an expensive undertaking. Good actors are quite rightly paid well for their powerful work and to exacerbate the price tag further narrative games often have hefty word counts (Röki for example clocked in at over 36,000 words). To fully voice a video game of this hefty wordage is an eye-watering prospect, and certainly out of our reach as indies. But we desperately wanted the emotional impact that voicing acting can bring, and we had a plan.

We worked with voice actors to create an ‘emote library’, essentially a collection of voiced sounds used to express a certain emotion, from tired yawns to frustrated grunts. We covered over fourty emotions in our recordings for each character. In-game dialogue lines were then tagged with an emote, and would trigger the specified sound to play when the line was ‘spoken’.

This approach came with a number of ‘wins’:

We got the human nuance and emotion we were after to elevate our dialogue

The emotes required a short two-hour session with each actor so didn’t explode our budget

The ‘emote’ voice over was universal as no actual words were spoken, so would work for all regions

The player could progress the dialogue at their own pace, they didn’t have to wait for a long dialogue recording to finish, or even worse, clip its wings mid-delivery.

We used Scandinavian voice actors exclusively on Röki. This was to aid our efforts in evoking a strong sense of place. The actor’s authentic accents come through subtly in their emotes, giving an extra indicator to the identity of our game world.

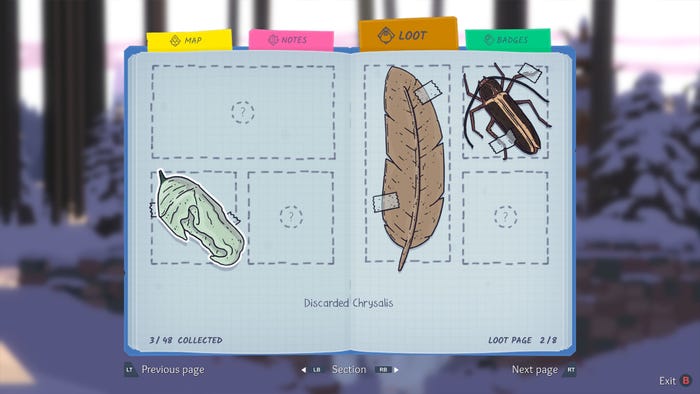

The Journal: Viewpoint and perspective

Lore entries in journals are no new thing. They give the player the option to delve deeper into the history of the game world, if they so choose. These entries can also be hijacked to give an extra insight to story and characters. In Röki the lore entries took the form of journal entries, written by our hero Tove in her notebook throughout her adventure.

There is a significant difference to these entries to her usual in-game dialogue.

In the journal she confesses her fears and concerns. These are the candid confessions she wouldn’t say out loud. It gives us a look behind the curtain of her bravado and allows us to convey a layered nuanced character formed of both her external projection (her spoken dialogue) and her inner, more guarded feelings (her journal entries).

Narrative Breathing Space

Kind of a weird one, but in a story you also need space for ‘no-story’. Many creative endeavors generate interest from contrast; whether it's a painting, music, film, or games. Contrast attracts the eye, ear, and mind and also gives texture to an experience. In games, giving breathing space within a game’s narrative can give the player a chance to reflect and absorb the events of the game and allow its themes to take root in their minds and resonate with their own life experiences.

In short, it gives the story a chance to take on a life of its own in the player’s brain noodles.

In Röki narrative breathing space is built-in as an intrinsic part of the game world. We designed 'empty' connecting areas of the deep forest to make sure that the game could never be too story-dense and provide time for reflection as part of the general gameplay. A different example is in the three trials that Tove faces; these gameplay sequences revisit and revitalize themes and story threads from the game's first act, showing them in a new light and nurturing previously planted story seeds. The time to reflect in this instance adds emotional weight as the story beats and their ramifications have been allowed to simmer in the player's mind before we revisit and re-examine them, uncovering new truths from different angles.

Result:

When we were working on Röki we imagined it would be perceived as a game about meeting fantastical folklore monsters and exploring the wilderness and were unsure how much attention the supporting story of loss, trauma, and the reforging of a broken family would get, if any. This might be due to a lack of confidence in our own storytelling ability. This was our first foray into the narrative woods after all so we didn’t really know what to expect.

To put it mildly, we were a little taken aback.

At launch, the story of Tove and her family connected with players on a level (that I have no qualms admitting) that we just didn’t expect. At all. We received so many touching messages from players telling us about the impact the game’s story had on them, how it resonated with their own lives, sometimes for quite profound personal reasons.

We were very humbled that the story landed so strongly with players around the world and firmly believe that’s why it was subsequently nominated for ‘Best Debut Game’ at The Game Awards and The BAFTA Game Awards.

For our first venture into the world of interactive storytelling we were pretty chuffed and it gives us great confidence for our next adventure.

Thanks for reading.

Read more about:

game developer launchYou May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)