Chris Crawford advises devs: 'Don't settle for the same old crap'

23 years after he charged out of the game industry with sword held high, Chris Crawford is still trying to revolutionize game development. Now, if he has his way, the revolution will be patronized.

“I’m old. I'm starting to have friends who are dying," says veteran game designer Chris Crawford. "One morning you wake up and you say ‘My god, what the hell have I been doing with myself for the last 30 years?!’”

Crawford says that's why, 23 years after charging out of the game industry with sword held high, he's still carrying the torch for interactive storytelling -- experiences that challenge people's social and emotional skills, rather than their mental and physical abilities.

He wants to light a fire under the game industry before he dies, one that other developers can use to light their own torches as they explore new ways of telling stories.

"I don't see a lot of intense ambition in a lot of game design these days," Crawford tells me. "I mean, your first game, you've got to prove you can do the thing: write the code, debug it, make it fun, and so on...but at some point you have to admit it's time for you to grow up, become a real game designer, and design your own game that's not merely, you know, 'Popular Game X' with a lot of tweaks to it."

If you were going to pick a word to describe Crawford's own career in the game industry, "ambitious" wouldn't be a bad choice. After creating a number of influential games in the '80s and effectively launching the Game Developers Conference from his living room, he's spent a significant portion of his life shepherding his dream of an interactive storytelling engine from its birth as Erasmotron in the '90s through its evolution into Storytron.

Now, with the backing of a new Patreon and the support of a coterie of developers scattered across the globe -- his "Knights" -- Craword continues to push interactive storytelling towards its hoped-for future as the flashpoint of a game design revolution that has always seemed perpetually just out of reach.

“I would call it the next revolutionary step, in that we are not talking evolving traditional games into this. This is a very different kind of entertainment...it will appeal to a different audience,” Crawford told me over Skype earlier this month.

“And ultimately, when the dust settles -- which will be maybe in 30-some odd years -- we will see current, conventional games doing exactly what they're doing now, albeit much better...and then there will be interactive storytelling as another field, that appeals to a different group of people.”

The way Crawford's toolset works is complicated (you can get a deeper look at it here) but the practical takeaway for developers is straightforward: Crawford wants to finish designing Siboot as a "proof of concept" of what an interactive storytelling experience might look like, then make the tools used to build it freely available so that other developers can build upon his life's work after he's gone.

This is well-trod territory for Crawford -- he admits early and often that he's been trying to make interactive storytelling a thing for over twenty years -- but now he's pushing ahead with a concrete plan to release his work to the public with a team of collaborators at his back and patrons' funding in his coffers.

Finishing a life's work

As of this writing that funding amounts to a bit less than $300 a month. Crawford says the money is mostly for the benefit of his team, six people scattered around the globe whom he says are currently volunteering their time to help develop Siboot and its underlying interactive storytelling technology.

"This has been my life goal for the past twenty years. I knew when I started it that it was something big, and I knew I’d have to finish it, one way or the other."

"This is really for the kids, like Alvaro," says Crawford. "To provide some income for the younger people on the team, who need the money."

He's referring to Alvaro Gonzalez, a Uruguayan game designer who lectures about game development at a private university who was also part of our Skype chat.

"I'm less romantic about this than Chris, because I'm younger," Gonzalez tells me. He serves as an art director on Siboot, and seems heavily involved in drumming up media attention for the project as a whole. "The way this industry moves is with money. It doesn't influence our vision...but I think money can make the difference. And we don't need much."

Of course, it was with those needs in mind that the team launched a Kickstarter campaign last month with the same goal: support Crawford's quest to deliver a "plug-and-play" open-source interactive storytelling engine, complete with a copy of Siboot as a proof of concept.

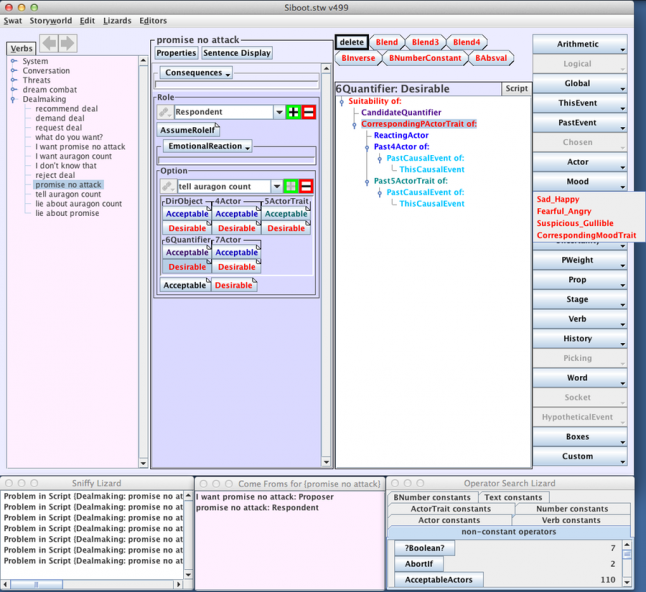

Here's what it looks like to work on Siboot in SWAT

That "plug-and-play" bit is especially notable for developers. After releasing (and subsequently taking down) an early version of his Storyworlds Authoring Tool (SWAT!) in 2008, Crawford says he's trying to make his interactive storytelling tech easier to use. The hope is that when he finally releases the toolkit, other developers will pick it up and run with it.

"Our problem with this technology is that the amount of busywork you have to do, relative to the tasks you face -- the amount of detail you have to pay heed to -- is simply too great," Crawford tells me. "So I'm going to scale back the amount of power, and thus the amount of effort required to use the technology. It will be simpler to use, but not as powerful."

And while his dream of interactive storytelling has proven to be less than a lightning rod for public interest (the Kickstarter campaign to help fund that work petered out with just under half of its $50,000 goal pledged) Crawford says he will continue to work on the project until either he or it is finished.

“This has been my life goal for the past twenty years. I knew when I started it that it was something big, and I knew I’d have to finish it, one way or the other, so…” he trails off, and my headset falls deathly silent.

After what feels like a long pause, he picks back up. “This is difficult for many of your readers to grasp, because the games community is so very young. Lots of people in their 20s and 30s...so this point of view that I have is rather alien, and a little hard to appreciate.”

An early alpha build of Siboot with various social behaviors and emotions rendered as simple icons

"I was Mr. Atari for a while, and gosh I was famous; it went to my head!" says Crawford, with a laugh. "And then Atari collapsed, and I was Mr. Nobody. Then I did Balance of Power and I founded the Game Developers Conference and I was Mr. Famous again! And...it really didn't mean anything. And then that all went away and I was Mr. Nobody again, and that didn't mean anything either."

"So I just decided: To hell with this nonsense, I've got important things I want to do with my life."

Pushing boundaries

In the wake of such a life, it's perhaps unsurprising that Crawford's number one exhortation for his fellow game makers is to not follow in his footsteps. Instead, he advises, make something new.

"Don't settle for the same old crap!" Crawford tells me. That's why he's impressed with the recent resurgence in indie development. "There are a lot of wild and crazy things being done by indies. A lot of it is crap...which is good! It means they're pushing boundaries."

But even as he dismisses the ups and downs of his career in the early game industry, Crawford says he still benefits from the lessons he learned back then.

"What we're doing right now is really just an echo of what we did 35 years ago," he tells me. He recalls starting out in the game industry in the early '80s, at a time when arcades were booming, home consoles were beginning to take off, and PC games were practically unheard of. "We knew that it would take years to build up that market, and we just plugged along and built it," says Crwaford.

Now he thinks the idea of an "interactive storytelling game" is nascent and weird in the way that PC games were in the '80s; before his death he hopes to help them break into the mainstream, just like PC games did in the '90s.

"We're establishing what is fundamentally a new entertainment medium; it's going to be slow going," says Crawford. "But that's the way it was 35 years ago; I've done this before, and I'll do it again."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)