Chris Bateman's journey from Discworld Noir lead to making Lords of Midnight tribute Silk

"Silk isn’t a commercially-motivated project," says veteran game dev Chris Bateman. "Silk is a debt of honor to Mike Singleton, one of a handful of absolutely brilliant British bedroom coders."

Chris Bateman is a game designer with a long and storied career in the games industry.

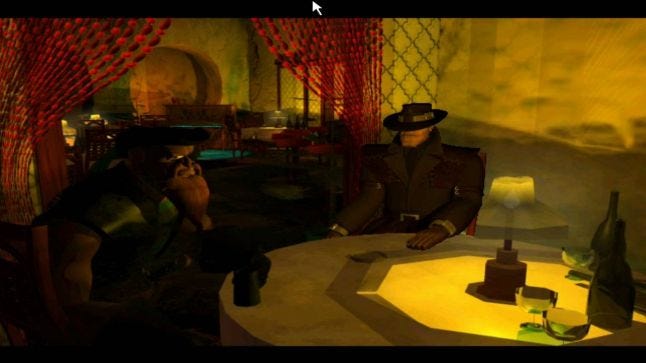

He’s worked on over 50 + projects, including the innovative point-and-click adventure game Discworld Noir, the puzzle strategy game Ghost Master, and Silk, his upcoming historical tribute to Mike Singleton’s RPG classic The Lords of Midnight.

On a surprisingly hot day in Manchester, we escaped to the gloomy interior of a hotel café in the city center to sit down with Bateman and discuss Discworld Noir, his video game consultancy company International Hobo, and his thoughts regarding video game AI.

What follows is a transcript of that conversation, edited and condensed for clarity.

So, how did it come about that you ended up having a more important role on Discworld Noir as opposed to Discworld II?

I joined Perfect Entertainment during Discworld II. I was junior designer and I was hired largely to support Gregg Barnett, who was the design director at the company. And largely, I think the reason I ended up being more involved was Gregg was tied up trying to sort out this Naked Gun point-and-click adventure game.

Don’t get me wrong, Discworld Noir conceptually was Gregg’s concept. The germ of it was a conversation between Gregg and Terry and then I was handed that mission and basically told to find some way to make it work.

To begin with, I was just doing research. I spent a year reading Discworld novels, reading Raymond Chandler, reading Dashiell Hammett, watching every noir black and white movie I could get my hands on. It was tough work, as you can imagine.

As the project went on, there came a point where Gregg left the company over disagreements with Angela Sutherland [the co-founder of Perfect Entertainment] and as a result, like I say, at the end of the project I was basically running it all on my own.

Gregg’s stamp is all over that game, but I ended up being lead writer and lead designer and it was only my second game that I’d worked on. I had no business having either of those positions, but I was very honored that I got that chance.

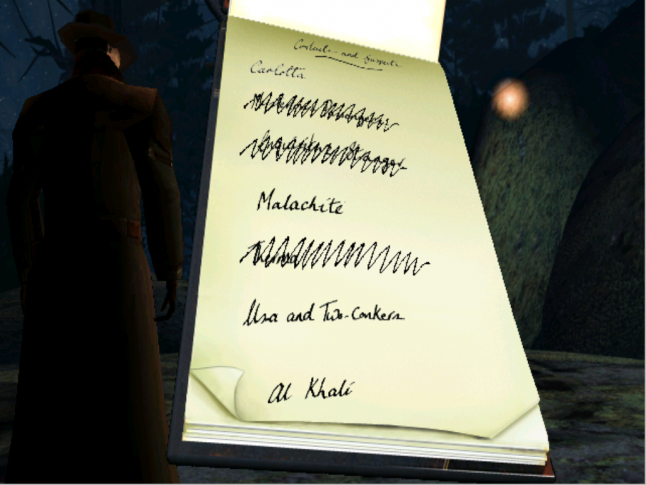

One thing people always refer to in Discworld Noir is the introduction of the notebook, which has become somewhat of an adventure game staple. I’m just wondering how you came up with the idea and what was the reason for doing it?

So, once I had been given the brief to find a noir way of pitching Discworld, I started looking at the options. And the thing I really wanted to do was find a different way of running the conversations. Adventure games had all been run off an object inventory that was basically lock and key puzzles. That felt really wrong for investigative games.

It came to me fairly early on that the answer was the notebook. Rather than using objects as triggers for the conversations, if you had a notebook that was organized by topic, then every one of those entries in the notebook becomes a trigger for conversation. The Tinsel Engine, which is what Perfect had done it in, made this a really easy situation, because Tinsel already had a code for an object and then the conversations that would trigger from it. So, all I did was put the notebook on the frontend, so instead of an object that was triggering those conversations it would be a topic.

The difficult part was constructing the scripts and making sure there was clever error handling. So that when you talked about a topic to someone, you wouldn’t just get “That doesn’t work”, which is the blight of the early Discworld games.

The error handling was designed to funnel the player towards more productive leads, and the whole thing was therefore this really diffuse web whereby there was so many cases in it, even I didn’t know all the different ways the players could go about solving some of the puzzles.

What suggestions did Terry Pratchett make about the script? And when did you know to push back and fight your own corner? Because that’s something that people who work on a lot of licensed games have to consider.

Yeah, I’ve worked on an awful lot of licenses over the years. But working with Terry was actually a lot easier than working with the large corporate brands. The thing is, it was important for him that anything that was in the game matched what was in his head, but for Discworld Noir the only things that we were using from the canon was City Watch characters and Death, right? So it was mostly a case of getting the City Watch characters and Death right.

In fact, the largest change was we re-recorded all of Captain Vimes’s lines, because Terry wanted Vimes to have the voice of the commanding officer in The Sweeney or at least along those lines. That isn’t the voice that we recorded. So we rerecorded all of those lines, which honestly was not that much of a big deal. But other than that, the only other thing that he completely overruled me on is he rewrote all of the Death dialogue. Death was always a character really dear to him and I’d been a little bit scared about writing for Death, so I largely pulled from stock Death dialogue, which was really chicken of me.

After Discworld Noir released, what was your reason for setting up International Hobo?

So, Discworld Noir had come into a situation where the point-and-clicks were already dying and Perfect couldn’t survive that really, so they were shutting up shop and it was a matter of what would I do next. And I had started dating a woman in the US, who is now my wife, and I literally started the consultancy so I’d have a legal means to enter the US and visit my wife by having a UK employer who I could state ‘I’m employed by this company.’

But once it was there, the thing it made sense to consult on was this relationship between game design and story. Because we were doing it very badly for the most part and still are to some extent. And the root problem is the techniques of screenwriters for TV and film, although they have some application in games, if you only take all of your story advice from that side you’re missing out on the interesting things that games can do narratively.

So, I had this intuition, that Richard Boon who worked with me on and off over the years on many projects shared, that if we wanted to do better stories in games we needed to get conventional writing skills and game design skills to talk together. So, we built the consultancy around bringing the two together.

You were also involved with several satisfaction surveys, such as BrainHex; what was the idea behind those?

The thing is, if you’re going to make games well, you need to understand what you’re doing, and the other thing that really struck me in the early days of International Hobo was most companies just assumed the player was like them, which enormously limited what you could do with video games. There was a self-selecting, self-fulfilling prophecy there. I wasn’t happy with that and I could see from watching people play games that there was a much wider range of ways that people were playing games than the industry was taking seriously.

So, we set up to do this series of player satisfaction studies, and BrainHex was the last of those. And there’s a reason it was the last of them, but I do still consider the surveys to be a success. They really helped us understand the wider range of reasons that people had for playing and that although competition and challenge are really key parts of many players’ enjoyment of video games they aren’t the whole story.

And how was that information then useful to you when consulting with studios?

This is about understanding what player motives are going to be relative to particular projects, right? So, this was key to things like Bratz: Rock Angelz, because nobody knew what a tween girl player wanted to do. So, we drew against psychological research and what was acknowledged as play loops for that particular audience and then applied that to the game design and the narrative design of the Bratz game.

I think it is this key thing whereby when you’re looking at a game every game has an audience for it. And the question is who is your audience for this? What are their motives for playing? Are there other audiences with slightly different motives that are compatible with what you are doing for that one? So, can you bring in more players with this game without completely remaking it, right?

Once you have an understanding of the different motives players have for playing games you can look at a game and say, ‘Right, your target is primarily this audience, but this other audience is well in reach for what you’re doing here.’

I guess the perfect question leading on from that is who do you think the audience is for Silk, which you’re working on at the moment?

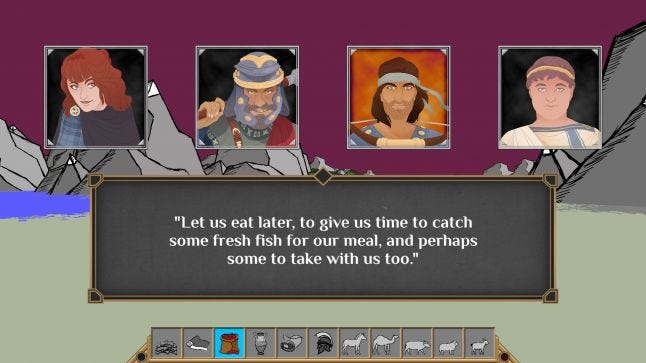

An excellent question, because if Silk had been a commercially-motivated project, we probably would have killed it a long time ago. But Silk isn’t a commercially-motivated project. Silk is a debt of honor to Mike Singleton, one of a handful of absolutely brilliant British bedroom coders.

The Lords of Midnight shipped on the ZX Spectrum where you only had 48k to work with, yet it is this brilliant unlicensed adaptation of The Lord of the Rings. I’ve always admired what Mike Singleton achieved in that game and it always saddened me that it didn’t really have any successors.

As to who the player for Silk is, I think the bottom line is this is a game for people who enjoy exploration and who want to tell their own story in a game world that they’ve been dropped in. And that’s what this game does. It drops you into 200AD and invites you to have your own story in that time and setting.

Silk seems to be quite a specific approach to using AI, with your party of advisors influencing what tasks you can carry out. Whereas now, the approach given a lot more prominence in games is behaviour trees and decision-making AI. Do you have any thoughts on your approach versus these other techniques?

My master’s degree was AI. And the main thing I got from studying AI at master’s level was the realization that AI was not what it was in science fiction at all, but is actually a much more specialized tool. And video games are doing a great job of exploring the things that AI do well, such as finding paths for units and various ways of processing a situation in order to determine a response. But AI is actually quite limited and the thing that makes games as a medium really exciting is that the player’s imagination is one of the tools that the game maker has to use to their advantage.

So, I think a lot of the really crunchy AI that you have out there the player doesn’t necessarily get the benefit of, because the clever stuff is under the hood and only the development team get to appreciate it. I think it’s noteworthy in something like The Sims. People fell in love with The Sims because they were given a virtual doll house and they enjoyed creating their own stories with it. It wasn’t because the AI was clever, because it wasn’t. It was because they were given these bunch of characters and left to create their own stories out of the stuff that happened. And I think the secret weapon for game narrative is the player’s imagination.

Even though I’ve got a background in AI, I’m usually looking to do as little as possible in terms of complex, crunchy artificial intelligence in games, because I think the player is a far better asset to the project than a fancy AI system. There are exceptions. But certainly, when you’re trying to create a narrative experience in games AI isn’t the way to do it. Give the player the opportunity to create their own stories with the tools you give them and I think that’s a sort of timeless lesson.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)