Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

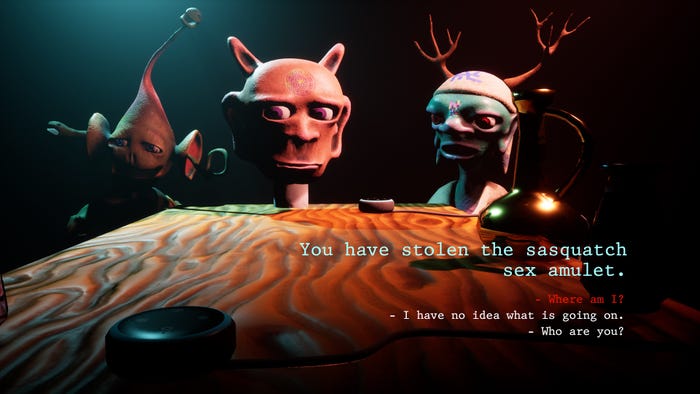

Road to the IGF 2022: Fuzz Dungeon is a journey through an absurd vision of human history, all so you can find a "sasquatch sex amulet."

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series.

Fuzz Dungeon is a journey through an absurd vision of human history, all so you can find a "sasquatch sex amulet." And recreate a society where you might not have to go to work. It's a surreal vision of existence, but one that captures the imperfect ways our good ideas tend to take shape when we bring them into the world.

Game Developer spoke with creator Jeremy Couillard and musician Chris Parrello about the IGF Excellence in Audio and Nuovo Award-nominated work, talking about how our ideas don't always come out quite as we imagine them, how the game's vision of reality mirrors the discordant, yet harmonious aspects of our own daily lives, and a look at how everything seems to be "gamified" at the moment.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Fuzz Dungeon?

Jeremy Couillard (creator of Fuzz Dungeon): I am Jeremy Couillard, a visual artist based in New York. I am the creator of Fuzz Dungeon together with collaborator Chris Parrello, who did the music.

What's your background in making games?

Couillard: I went to grad school to study painting and slowly moved into animation and messing around in game engines. Fuzz Dungeon is my fourth project on Steam. I have no formal game design or programming training. All my foundations are in the visual arts…but well, obviously, I think video games are, at their core, a visual art!

How did you come up with the concept for Fuzz Dungeon?

Couillard: I was trying to draw, I think, Mickey Mouse or some cartoon character like that. I saw it perfectly in my head, but when I went to draw it, it just looked awful. And then I thought that was a great analogy for how we live as humans sometimes.

We have these great ideas that we see perfectly in our heads, but when we go to get them out they are never what we originally intended and often look like monsters. And this can scale way up. Like, the inventors of social media did not anticipate their infrastructure to contribute to the rise of fascism and mass surveillance, and Henry Ford didn’t think the mass production of automobiles was going to contribute to rising sea levels and cities becoming way more ugly and inhospitable.

I wanted to make something that was self aware of that process. Instead of the usual workflow of having clear and ambitious ideas for a game and executing them, I wanted to work in a looser style and make things up as I went along—make things that were very personal and about my life as I was living it while making the game. Maybe all this plotting and planning isn’t so good a lot of the time and only gets us chimeric monsters that come back to eat us alive. Maybe there are other ways to do things? Or maybe not. I don’t know. I just wanted to experiment with it.

But, well, being nominated at IGF is meaningful because it sort of answers that question to some extent. If you’re persistent you can be your weird self and some people will be able to relate.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Couillard: I used UnrealEngine 4 primarily, as well as Blender, Zbrush and Substance Painter.

Fuzz Dungeon features a unique protagonist. What thoughts went into its design?

Couillard: The process for all the characters was pretty much the same. I would just open up Zbrush and start doodling. I was really inspired by this series of drawings by William Blake called Visionary Heads where he drew ghosts or spirits he claimed to be looking at. The drawings have this awkward gaze and uncanny valley feel to them. I was trying to capture something similar to that.

I felt that when I opened up Zbrush to sculpt a character, rather than looking at spirits in the classical sense, I was looking at the ghosts of pop culture detritus that haunt my subconscious since I can remember. The Flip character is just an amalgamation of all the cartoons and video games I have played throughout my life…but I wasn’t necessarily trying to make her appealing or attractive. She’s an embodiment of that failed attempt at drawing Mickey Mouse from memory.

The game takes players to a variety of different places, many with different looks and play styles. What challenges came from creating this kind of variety, and how did you deal with them?

Couillard: The challenge was that it was just a lot of work [laughs]. We were mostly in lockdown, though, so I had a lot of time. I guess I also had to find a way to connect everything in a way so the players could navigate the game space, so that’s why I put it in a sort of dungeon cave with different buildings used as access points to the different worlds.

Likewise, each of these worlds has a visual style. What ideas went into creating so many different styles? In making them feel like they are still connected with the core designs of the characters?

Couillard: I wanted the experience to be an analogy of living in our contemporary world. Watching TV, scrolling through our phones, walking down the street—there is so much variety to capture our attention, but it’s all mediated through the commonality of our global culture.

So, I can walk down a city street almost anywhere and see an animated advertisement reminding me to wear a mask, a billboard for a lawyer, cabs with ads for strip clubs, street signs, people with logos on their clothes etc. But this is all in a different “style,” and at the same time all somehow makes sense and is perfectly understandable. No one is walking around totally lost and dumbfounded (or very few anyway).

It’s all just part of living in a city, which in itself is just a big hallucination we’re all having together. It’s a thing we just made up and are sort of rolling with, making it up as we go along. I wanted to create an experience that was like that. Sometimes I feel like games and animations are too tight in their design and it doesn’t reflect the more patchwork reality we experience in our day-to-day lives.

What were you hoping to evoke from the player with these various looks and visual styles in Fuzz Dungeon? With this "absurdist version of human history"?

Couillard: I think history is a sort of Fuzz Dungeon…it has been full of great ideas that didn’t work out how the original thinkers had hoped. And also, as we conceptualize history, we often do it through events that didn’t actually happen how we think but fit our current ways of understanding our world (i.e. we call agriculture a ‘revolution’ but it took around 3,000 years to fully implement).

I wanted to play with this simplified version of history we tell ourselves and use it as a metaphor for how everything is gamified nowadays. We even think of history as a way of “leveling up” when really it’s way more amorphous I think.

What thoughts went into getting the music and audio right for the game?

Chris Parrello (musician for Fuzz Dungeon): Fuzz Dungeon is a variegated visual experience—it does not look like one thing—it is hand-drawn, pristine digital, 8-bit... Jeremy is a master of many modalities. But the feel of the game is constant. I wanted to explore different modes of music-making (live instruments, samples, chiptune), hopefully with similar integrity, and also maintain a common spirit. Not austere, but inviting serious questions. Sometimes it's beautiful.

What made the score feel right for this surreal experience?

Parrello: Perhaps dressing up serious ideas in ridiculous clothing? Or sometimes the opposite.

What interested you about exploring the connections between ideas and consequences through this game? What were you hoping to convey through this work?

Couillard: Ultimately, I guess I just hope people feel they went through a unique experience when they finish the game, and maybe feel that they connected with me on some level (that’s why one of the last levels is literally my living room where I invite players over to look around). And then, if they think about it a little more, I was hoping to convey an idea that things can be different.

A good video game doesn’t have to be a slick product with nice mechanics and a tight visual style. An artwork doesn’t have to be a painting on a wall. A society doesn’t have to be driven by grandiose, individual ideas and market economics. Living in the world is a strange and sad and beautiful experience and we can experiment with doing things in hundreds of thousands of different ways.

Things feel a little stuck lately, so in part I want to convey a hope of the possibility of being a little less so.

This game, an IGF 2022 finalist, is featured as part of the IGF Awards ceremony, taking place at the Game Developers Conference on Wednesday, March 23 (with a simultaneous broadcast on GDC Twitch).

Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2022You May Also Like