Building replayability into the macabre gameplay of Kindergarten

“I had the worst school experience. I hated every minute of it," says designer Connor Boyle. "I guess I took some of my dark, abrasive cynicism and channeled that into the game.”

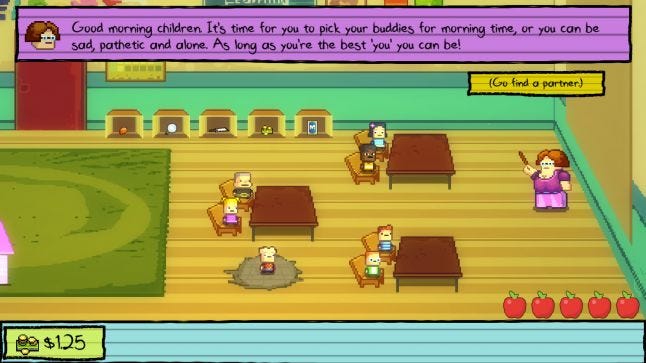

Kindergarten is perhaps best described as Groundhog Day meets South Park. You play as the new kid at school, who must repeat the same day over and over to solve a series of mysteries plaguing the various characters. The problem is that each day you can only perform a certain number of actions.

To make the most of each day, you’ll have to manage your time effectively, picking and choosing your objectives wisely. That way you’ll be able unlock the different pathways, and find out what exactly is happening at this disquietingly strange school.

Connor Boyle and Sean Young, the lead writer and artist on the "abstract puzzle adventure game" Kindergarten, both recognized that endlessly repeating the same day could be a problem early in development.

They knew that they had to make the repetitive structure enjoyable, like the movie Groundhog Day, and not rote and dull, like actually attending elementary school.

They succeeded. The game has found an enthusiastic audience, racking up almost 100K sales since its June 15th Steam release and garnering extremely positive user reviews on the site. To increase replayability and avoid player boredom, Boyle and Young employed dark humor, collectibles, and pixelated gore.

The germ of the idea

Kindergarten was a vastly different game in the initial conception. It originally started out as a horror title, with slight rogue-like elements.

The two developers shifted to a new direction, however, after Young began working on the initial artwork for the game and suggested that it follow a group of children in a school. “Our whole perspective on the project just shifted immediately. So we started working on the idea of a really messed up school instead.”

What was initially conceived of as a horror game became a game about the horror of grade school.

It was then that Boyle’s memories of his own childhood experiences (and his sense of humor) became the main influence on the project. “I had the worst school experience. I hated every minute of it," he says. "I guess I took some of my dark, abrasive cynicism and channeled that into the game.”

Black humor

"Most school days began with fights, a mugging, and gratuitous deaths. "

The dark humor in Kindergarten is one of the most notable features. It’s also extremely effective at keeping the player’s attention.

Take, for example, the opening where you first arrive at school. You have to play this scene several times throughout the course of the game.

Boyle therefore injected it with tons of outrageous moments, like a mugging, a schoolyard fight, and several gratuitous deaths. These instances help to prevent the scene from becoming tiresome.

Boyle says, “The shock factor really helps in the repetitions. Most of the writing came from Sean’s art. I did all the writing, but he would give me a room and then he would throw something wacky in it, like the bloody bags in the bathroom.”

The school janitor has to deal with a lot of unnerving stains in Kindergarten

The school janitor has to deal with a lot of unnerving stains in Kindergarten

He compares it to the sick humor of the cute-but-gruesome Happy Tree Friends cartoons. “The first two or three seconds of a Happy Tree Friends video is just cute and adorable, but it descends so quickly," says Boyle.

"I love that kind of contrast. From pure innocence to complete vulgarity and violence. And it hits you in a way that other types of gore don’t.”

Adding variety and collectibles

Of course, the game couldn’t survive on just shock humor alone. That’s why Boyle was careful to include a range of activities for the player to do. In every room, you can perform multiple actions, and in some cases still have enough energy to explore other interactions for your future runs.

The number of actions you can perform each day in Kindergarten is indicated by the number of apples that appear in the lower right hand side of the screen.

“To make it less tedious and repetitive, we tried to make multiple paths for every sort of room,” explains Boyle. “So if you did go in and you did it one way, and you needed whatever item to complete whatever mission, next time you went in…there’s something else you could finagle out of the situation. You could’ve got some money for it or, a Monstermon card.”

"Everybody loves collecting cards. It was just the perfect way to extend the gameplay."

Monstermon is the game's parody of real-life CCGs that real-life elementary school teachers are so prone to confiscate. The cards are the main collectible you can find throughout the game. You obtain them by completing quests, exploring secret areas, and experimenting with items on different characters.

Because it’s possible find a new Monstermon card every time you play through the game, this feature significantly reduces the frustration a player might feel at messing up and not getting their desired ending. It isn’t just useless filler either, as collecting all the cards has its own reward, in the form of another secret ending.

“Everybody loves collecting cards, and it was the perfect extra thing for people to 100% the game with,” says Young. “To get every Monstermon card, you’ve got to actually go through and do some wacky things, and a lot of extra things. It was just the perfect way to extend the gameplay.”

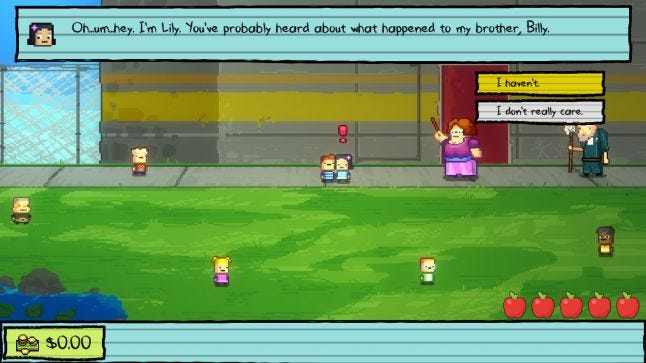

Keeping dialogue short and sweet

Boyle also tried to ensure the dialogue was as concise as possible at all times, to avoid the player becoming bored at repeatedly having the same conversations. One notable example of this was with the mugging scene that occurs if you bring more than $3 to school.

Conversations in the game are brief and to-the-point. And exceedingly creepy.

Boyle recounts, “Originally, that scene was going to be a bit longer, but then I realized that you’re going to get mugged by Buggs most days.. So I shortened it down to something like two or three lines, so you can mash through them.”

“Also, if I felt like the conversation was getting a bit stale or the characters weren’t talking enough, I would try to give the player something else to do," he adds. "If it’s not feeling strong I don’t want the player to have to sit around and have a conversation with a boring character."

Succinct conversations leave players more time to deal with other issues. Like figuring out what exactly those strange devices that the principal is implanting in children do.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)