Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How exactly did Harmonix and RedOctane create the original and seminal Guitar Hero, from concept to reality? In this extract from Iain Simons' book Inside Game Design, designer Rob Kay explains the genesis of the project in detail.

[Below, Gamasutra presents an excerpt from Iain Simons' recent book, Inside Game Design, courtesy of publishers Laurence King. Filled with interviews and graphics that illustrate exactly how top minds approach the design question, the book offers a look at everything from little-known indies to massive success stories, as with the interview we reproduce a portion of below: Guitar Hero and Rock Band developers Harmonix.]

Harmonix Music Systems has a mission. Lots of videogame developers have them, but they are in most cases relatively non-specific intentions to make innovative, original and brilliant new videogames. Harmonix is rather more specific. MIT alumni Alex Rigopulos (CEO) and Eran Egozy (CTO) didn't even start the company to make videogames; their aim was "to create new ways for non-musicians to experience the unique joy that comes from making music."

The studio developed music-led interactive attractions for a variety of theme parks before moving into game production with the critically acclaimed Frequency in 2001.

Global recognition hit with the release of Guitar Hero in 2005. This perfectly executed title made rock stars of anyone who wanted to step up to the PlayStation and grasp the guitar controller the game shipped with. The coverage and acclaim the title received were extraordinary, and it was adopted into that hallowed (and small) group of titles that even people who don't like videogames are allowed to like.

Along with Buzz and Singstar, the videogame became a welcome addition to many a house party. It shared a lot with these titles, mainly the ability to bring about extraordinary transformations in whoever played it. The space in front of the television was transformed from being the place where you play the game to the place where you perform.

The design of Guitar Hero was led by emigrated Englishman Rob Kay, who discussed the experience of making the game over the phone.

How did [the Guitar Hero] project concept emerge?

RedOctane had been talking to Harmonix for a while. It was a rental company and then they made dance mats for DDR [Dance Dance Revolution]. It ended up selling a bundle of these dance mats and wanted to progress that side of its business. The company was interested in making a guitar game as they'd seen Guitar Freaks, which Konami had done. So they came to Harmonix with the request, "will you make us a great guitar game for our new piece of guitar hardware?"

The peripheral led the project?

Yes. At that time, Konami hadn't released Guitar Freaks in the US, and I don't think RedOctane had any particularly grand ambitions other than needing a game. Relatively speaking, it was a pretty low-budget game -- about a million dollars, which is pretty tiny as a game budget.

We had a team that had just been freed up, as we'd just finished AntiGrav. This seemed like an awesome project. Everyone here was really psyched to work on a rock guitar game; it really fitted in with people's interests here. No one had any notions about it being a massive success; we all just thought it would be fun to do.

When RedOctane came to you with the request for a guitar game, how much of the detail of the project plan and the peripheral detail was already in place?

Basically, there were a couple of third-party guitars out on the market already for Guitar Freaks. When it began there was no hardware of our own as such, so we used those third-party ones.

Our first port of call was to get the beat matching up and running using those. Our first visuals for that were like super-basic Pong-style graphics with white markers coming down the screen as the gems to match the guitar part [gem tracks/gem authoring: terminology used inside Harmonix to describe the beats on the tracks that the player has to hit.

These are visually represented as little circles or gems within the game; e.g., on expert difficulty there would be one gem for every note within the song. To create easier levels, notes are removed -- one gem for several notes].

It was pretty fun; the controller really was the kind of magic sauce for what we wanted to do. It's very difficult to make games attractive and accessible, and I'm sure that 90% of what draws people into Guitar Hero is that plastic guitar. They instantly say, "I get it! I pretend to be a guitarist!"

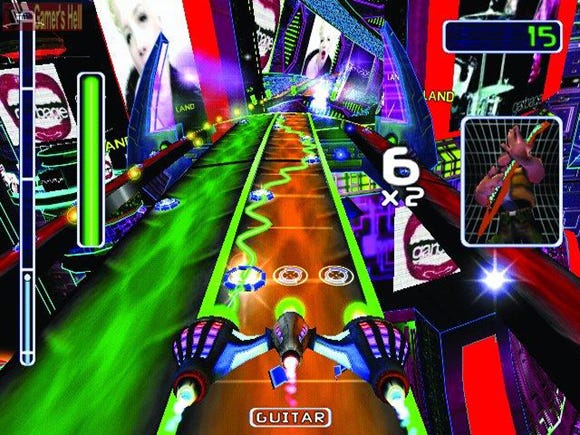

The popular rhythm action game Guitar Hero

Music is an easy shorthand for a lot of people.

It's a universal language. It makes it so much easier to make videogames reach out to more people.

Did you have a sense at that time of the visual stylings; the kind of cock-rock excesses you were going to be reaching for?

In our pre-production period, when we were doing the gameplay prototypes, we were also developing the art. Our art lead, Ryan Lesser, was very involved in the East Coast rock scene; he'd been involved in making posters for gigs, so was heavily immersed in that kind of world. The design really spawned naturally from people's interests -- it wasn't as if they had to do a lot of research.

Were the key tracks in place when you started designing?

No, not at all. As we started designing the game we didn't know what the tracks were going to be. We had a wish list, but little control over it. As the project progressed, we gradually found out what the tracks were going to be. The music licensing process takes a long time, so we had to overshoot.

We wanted 30 or 40 songs for the game and put a hundred on our wish list. As songs arrived, we needed to adapt the list according to what we could get -- which were the easy songs, which were harder, which were popular, which were more niche. We had to constantly adapt the track list to balance those concerns as the licences flowed in.

Are you a musician?

Erm. I'm a drummer!

I think that counts.

I like to think so. The background of around half the people here is musical, but it's really important to have people that aren't too, to get that perspective in place on projects.

In our first prototype there was almost nothing on screen other than a simple 2D track. One of the things we learnt from Frequency and Amplitude was that people don't necessarily relate to really abstract visuals; they don't always understand how they apply to them.

From Karaoke Revolution, one of things we did was to put this whole musical creation idea into the context of a live performance. We aimed KR at people who had never played, and we decided to pull that approach over wholesale for Guitar Hero.

In terms of the gameplay, there were really two main threads. One was the core beat-matching gameplay and making that as awesome as possible; making sure that moment-to-moment feedback was as good as it could be to create the sensation of really playing a guitar.

Amplitude for the PlayStation 2

The second thing was that as you'd be playing the guitar all the way through in this, we were going to need another layer of gameplay. That was where the idea for star power came from. That was there to provide a little more depth to the game -- some replay value, some interest for people as they were playing beyond just hitting the notes.

Also, a big part of rock is showmanship, and we wanted to find a way to explore that in the gameplay. The third problem was that we wanted to have tilt and a whammy bar, not so much as music inputs but as performance devices. We spent a lot of time discussing how that could be implemented, which ended up in the unified solution using star power.

How concurrent are these design strands, the controller development and the game development?

They were pretty much concurrent. We were pulling songs into the game pretty much constantly until ship. The licensing and recording process loop was going on all the way through production. It would be great if you could finish piece A of a project before moving on to piece B, but it rarely works like that. The way to solve it is by iteration: as the pieces begin to fall into place and you can see them responding to each other, you can evaluate and make design decisions as you go.

Presumably that forced you to revisit earlier song levels once the hardware features had all been finalized?

Yes. Most of the tracks went through some gem-track re-authoring, mostly for difficulty and authenticity issues.

What's the process for creating the gem tracks?

We have an authoring team who develop a feel for these tracks over time. It's about working with a track and being able to spot the key notes that will make you feel as if you're a brilliant musician.

That first pass might take as little as a day for a single song. We have a pretty large QA [Quality Assurance] team who can give them feedback on where it feels good or where particular difficulty spikes are.

We also created some software into which you can feed a gem track; it gives you a difficulty rating back based on some rules that we've given it. By comparing those on a graph once the songs are in order, it becomes easier to make revisions to the set list -- either by reauthoring or by moving songs around. So the initial process is relatively quick; for us the detail is all in the iteration.

[The remainder of this interview, also including prototype images of Guitar Hero and the guitar peripheral, as well as other interviews and insight from Keita Takahashi, Michel Ancel, David Braben, and other creators, is available in Simons' book Inside Game Design.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like