Narrative design in pursuit of authenticity in musical biopic We Are OFK

"There has to be a confluence of who [the characters] are and the choices they make in the game."

We Are OFK is a strange and wonderful thing. The latest brainchild of Hyper Light Drifter co-designer Teddy Dief, the project is billed as a music biopic game slash interactive e.p. that blurs the lines between fiction and reality by turning a virtual band into one that will release music, post on social media, and perhaps one day even play gigs.

Sitting down with Dief ahead of the game's launch, the We Are OFK director, writer, and lead singer explains how the original intent was to release something akin to a sitcom based in Los Angeles, largely because Dief wanted to lean into the old adage that tells people to "write what you know" in a bid to create something authentic.

Dief spent the first six months of the project narrative prototyping, building out each of the band members as individuals with their own unique personality traits and perspectives before attempting to mesh a them together as part of a broader, cohesive storyline.

Who are OFK?

"[At that early stage] there was a bunch of character development that went on for arguably too long," Dief says, explaining what it was like feeling their way into the project during those formative months. "The nice thing about working on a game is you can simmer on your story and then pivot and work on mechanical stuff and it never feels like you're fucking around. You know, I was being productive even though I was afraid of doing a second draft of my character sheets."

Dief says they wanted to emulate sitcoms by giving the actors playing each character the freedom to inform how each one would take shape. Although it was impossible to emulate that process on a 1:1 basis -- because in television they'd be producing episodes and releasing them on a cycle -- the OFK team decided to cast their actors earlier on in the process so they could do rehearsals and "find the Venn diagram of [...] how we hear the character, and how the actor is hearing the character."

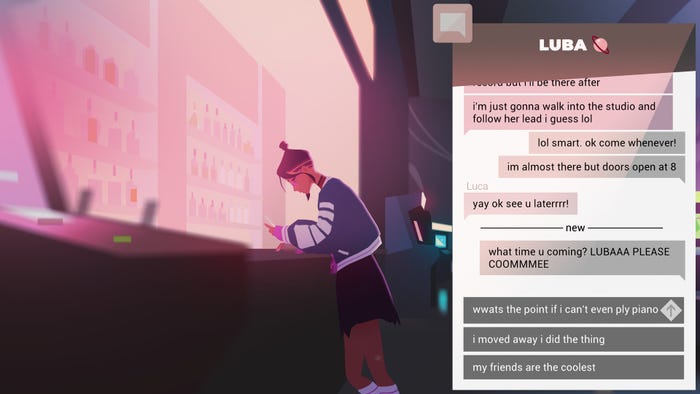

"That made it easier to ask 'what would this character say, and how would they say it,'" Dief explains, noting how they also sought to make texting in-game feel more authentic by settling on unique syntaxes for individual characters and questioning whether they would use proper English or slang based on their established personalities.

Dief also notes how the music in OFK informs its roster. In an early draft of the script Itsumi Saito (one of the first characters we meet) played the cello. Eventually that was switched up to make her the band's keyboardist because it made more sense based on how the tracks themselves were developing.

Tracks would also be shuffled around in each episode to better reflect the emotional state of those characters in the spotlight. Dief explains they were incredibly focused on ensuring OFK excelled when it came to both pacing and delivering authenticity, and sometimes that meant a little bit of trial-and-error.

"Episode Two in particular was where the structure changed most strongly. The second single 'Fool's Gold' has more gravitas than I thought it would and so it needed more build-up," they explain. "It was initially played a little bit earlier in that episode, and then in the edit I moved it much later because it hadn't been earned yet. It was like 'oh shit, this song is pretty serious' and we hadn't gotten into the darkest place yet, so let's not go rushing in."

Music sounds better with you

Another constraint born from OFK's musical ambitions was that, for all intents and purposes, these characters exist in our world. Dief explains that the ultimate aim was to launch a band, so when writing the narrative they couldn't go all-in, Mass Effect-style, and start hitting players with seismic choices and twists.

"We can't be like 'is the band going to break up or is someone going to die?' because they're already on Twitter -- they were on Twitter two years ago, so there has to be a confluence of who they are and the choices they make in the game," Dief adds.

The OFK director says that mantra informed how the music videos themselves were implemented with interactivity in mind. OFK is a musical game, not a music game, and that means players won't be asked to play -- and potentially flub -- tracks when they're introduced in-game.

"One of the constraints that I wanted to set up for the music videos was that we're not testing your musicality," Dief says. "We are inviting you into the music, right? You should not have the opportunity to ruin the song like you're playing Guitar Hero or Rock Band or something."

That design choice was also made in service of approachability, and while Dief concedes it demandand certain requirements be met when designing the interactive mini-games and reactive audio beats baked into OFK's musical moments, it also gives more people the opportunity to experience the game and have fun with it.

"There were originally some music sequences that took place outside of the proper music videos -- and we still do have moments where we tear apart the stems of the songs and feed them into the story a little bit -- but we're not really a game that asks players to watch the songwriting process unfold. That's not our focus. Our focus is on the people and the spaces between."

During our chat, Dief details how keeping OFK lean was a top priority from the outset. The episodic nature of OFK -- the title is being released as five episodes -- is designed to keep players engaged without burning them out. In the words of Dief, these days "shorter is usually better."

"Everybody's tired, especially people coming from outside of games -- they're not used to sitting down with anything for longer than an hour," suggests Dief. "[It's the same] with people who play games. I love long games, but I don't play any game that's longer than six hours anymore."

That dedication to trimming the fat with pinpoint precision led to plenty of cuts and design tweaks throughout development, with those tough choices ultimately being made to streamline production, deliver intentional pacing, and ensure OFK was as approachable as possible.

For instance, in OFK players are often invited to engage with the narrative by choosing how to reply to a text or respond to conversational prompts. To ensure those moments don't cause massive pacing hiccups, Dief and the OFK team encourage players to impose an optional 10 second window on themselves when making those decisions -- though, of course, some might decide against that for accessibility reasons.

"Originally, every choice had a bespoke timing setup, and that's common in narrative games. There'll be narrative games that have decision timers built around different speeds of choice, but we cut that [from OFK] because although it was an interesting narrative design choice, it wasn't an honest reflection of the player experience," says Dief.

"Our player experience is one in which you're asked to interact about once a minute or twice a minute, with the exception of the music videos. So we can't be like 'oh, here comes a quick decision! Make sure you're still paying attention' because that would punish players for doing exactly what we want them to do and relax. You know, maybe their friends are there and they're talking. So we decided to make a universal rule and add those 10 seconds because we felt it would give them enough time to respond without completely killing pacing."

Script changes were also made to keep production on track, with Dief choosing to reign in the number of environments OFK's cast of characters would visit and scrap certain interactions to relieve pressure on the project's artists and animators.

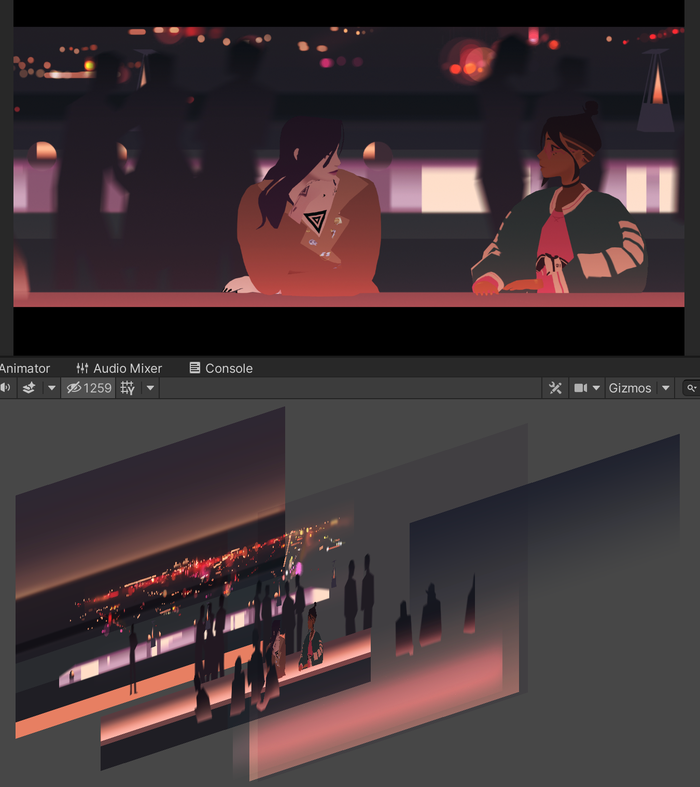

Dief explains how all of the scenes in OFK are built from scratch, and admits to being "caught by surprise" at how much tinkering it would take to ensure each one hits the right mark. "So much of the visual design is manual," they continue. "Every character is repainted for different lighting environments, much like they would be in animation. Every environment is completely repainted for different lighting setups. None of the environments are 3D, they're all hand-painted and characters are folded into them.

A diorama of a scene in We Are OFK

"When we're folding them in, we have to manually occlude them in some ways. Sometimes there were problems with the order of things -- for example, characters might be both under and on top of the same object, and you have to deal with that in a very manual way. Most of the labor of this project, especially in the last two years, was just the tinkering."

Although the core narrative beats remained the same, the sheer amount of work that went into realizing each of those environments resulted in Dief cutting locations from the script. For instance, there was initially a Boba Tea shop that was going to be introduced in the second episode that would become a staple for the show. It was also going to be the basis of a running gag that would've revealed that shop was actually a series of different locations within the same chain (sound familiar, Starbucks?), but it eventually had to be ditched because it was impossible to move the assets around effectively because of the bespoke makeup of each environment.

Getting animated

There were plenty of animation script cuts, too. Teddy and co-writer Claire Jia would throw stage directions into the script -- such as having one character hand an item to another before they toss it aside -- which would've caused massive headaches for OFK's animators if they'd actually been implemented.

"I think one of the hardest things about making a game that's not action-based is trying to figure out motion. Like, most things aren't moving most of the time. Even on this Zoom call, nothing around me is moving. Kurusawa would just make it rain in the background, and Miyazaki would put some clouds in the background. We do a little bit of that stuff, but it was a challenge to get motion in there while also trying to get comfortable with the fact that [sometimes] things aren't moving."

A variety of expressions created for Itsumi Saito

Dief notes that OFK's art direction means it couldn't mimic the visual gags that have become a staple of sitcoms, and although there's a lot of manual face performance in the game, there's also a scope to the number of facial expressions each character can have. To tackle some of those animation challenges, the team made a number of tools that could be used to streamline and automate seemingly trivial facial movements like blinking and head turns.

"That helped a lot too because it alleviates the pressure on animation. It's not like we hand animated every frame of this game," Dief adds. "We're mixing and matching a lot of animation layers so that our lead animator could sleep and have hands that work, y'know? We're very crunch averse. So much of our animation is based on static poses that are built out using lot of layers so they feel alive."

OFK are here to stay

The plan moving forward is to continue fleshing out the story of OFK, but Dief isn't sure exactly how that'll play out. If players respond well to We Are OFK and buy into the notion of a virtual band that can transcend the digital world, more episodes could be in the pipeline, but there's also talk of using apps and social media to give the band a louder voice and allow fans to interact with the pop ensemble outside of the game space.

Before that, however, Dief has their sights set on performing in the real-world. Following in the footsteps of other musicians that play fast and loose with the notion of reality such as Gorillaz, Daft Punk, and Riot Games' virtual K-pop group K/DA, Dief talks about using projections and other technology to put on live shows and start writing the next chapter of We Are OFK's narrative in real-time, taking the band on a very real journey from newly-signed pop prodigies to (whisper it) perhaps even loftier heights.

"We actually wanted to launch a pop music project," says Dief. "So that means touring live but starting small, because that fits with the framework of our story which is a home-brew, slice-of-life narrative. We're trying to make characters who feel human size. We're not trying to make pop stars."

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)