Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

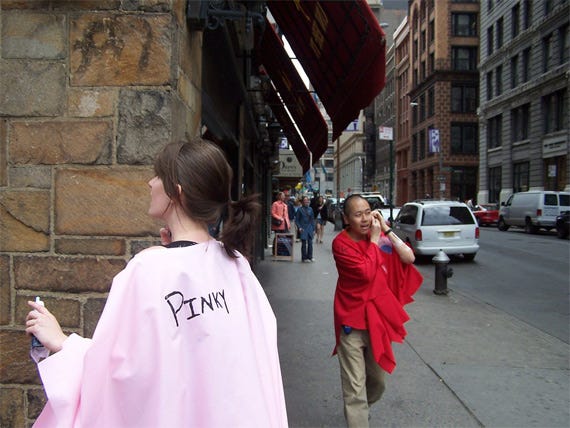

Do 'big games' like <a href=http://www.pacmanhattan.com/>Pac Manhattan</a> act as constructive social and gaming experiments, or are they excuses to run around city streets in ghost costumes? We asked area/code founder Frank Lantz, in this exclusive Gamasutra interview.

Frank Lantz is the creative director and co-founder of area/code in New York City, a developer that works exclusively on 'big games,' described by area/code's website as "large-scale, real-world games. A Big Game might involve transforming an entire city into the world's largest board game, or hundreds of players scouring the streets looking for invisible treasure, or a TV show reaching out to interact with real-time audiences nationwide."

Previously, he has worked as the director of game design at Gamelab, the developer behind the mammothly successful casual game Diner Dash, and as a game developer for POP. He also teaches in NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program.

Gamasutra: Could you describe, in your own words, what area/code does?

Frank Lantz: We create what we call Big Games – games that mix digital, electronic, and virtual elements with some form of real-world presence. These games are usually large-scale, multiplayer games that involve physical activity and face to face social interaction. They often take place in urban settings or other public spaces.

GS: How do "big games" differ from "alternate reality games"?

Frank Lantz at GDC 2006

FL: We see ourselves as exploring a similar territory but with a different focus, or perhaps a broader approach. ARG’s tend to be very narrative-driven. The standard ARG structure is built around some kind of mystery story that the players are exploring, and progress through the game usually takes the form of collaborative puzzle-solving which unlocks access to additional story elements. We see Big Games as more gameplay-driven. You might have a Big Game with a rich, complex narrative, but you could also have a Big Game that is totally abstract.

The games we make often have elements of collaboration, but also usually have some form of player vs. player competition, and are less about puzzle-solving and more about skill, tactics, and strategy. In general our games are more procedural, and less content-driven.

Also, ARGs seem to be more invested in the pleasures of confusion, about creating ambiguous situations where you don’t know whether what you’re looking at is part of the game or not. In the games we’re making we usually try to make things really clear and simple, so the players know exactly what the game is and what they’re doing (which is hard enough to achieve even when you’re shooting for it!) so this makes them perhaps a bit more accessible to a casual player. But in general we love the experiments that are taking place in the ARG world, and see all those guys as fellow travelers. Real-world stuff like Jane McGonigal’s Tombstone Hold’em, which was part of 42’s Last Call Poker ARG, are especially interesting to us.

The University of Minnesota-commissioned Big Urban Game.

GS: The logistics of a "big game" might be hard to imagine right off the bat. In a given game, who decides the premise/gameplay? Where do participants comes from? Who's the target audience?

FL: Big Games are designed just like traditional computer games or analog games – the game design team creates the premise and develops the gameplay then refines it through playtesting. Sometimes games are designed for a particular setting, like a conference, where the players are the attendees. Sometimes the game is “open” and has to recruit players for itself. The target audience could be anyone, although sometimes its limited by technology to people with cellphones, or people with laptops or whatever. But basically, we see the audience for Big Games as anyone who wants to try something new.

GS: What is area/code up to at the moment?

FL: We’re working on a big project for an entertainment company that is built around a popular TV show and will go public late this year. We’re also making a game called Crossroads, which is a tight, little two-person strategy Big Game inspired by aspects of Mardi Gras culture that we’re designing for an exhibit about urban culture at the Van Alen Institute here in New York in September. We’re working with a group called the Girls Math and Science Partnership to create a science-based Big Game for high school girls. We’re doing some brainstorming with the folks at Disney Imagineering to help think about how the Disney parks could evolve to include game experiences. We’re working with a cool company in Japan called Geovector which has a technology that can tell you which way your cellphone is pointing. And we’re developing a game for Come Out and Play, which is an upcoming urban gaming festival organized by some of my former students. Among other stuff!

Big game Pac Manhattan in action.

GS:Why did you make the switch from electronic to real-life games in your own career?

FL: I’ve always been interested in experimenting with new kinds of games and game structures; I’ve also always felt that digital games were more properly understood as a subset of games, rather than as a subset of computer media. In other words, for me Counterstrike has more in common with tennis and golf than people tend to think. Ditto for World of Warcraft and Chess. So I see the transition as being more a matter of focus, rather than a big leap. Early on, I had a bunch of opportunities to create games for conferences which were fun, small-scale experiments. And then I got invited to create the Big Urban Game, along with Katie Salen and Nick Fortugno, for the University of Minnesota Design Institute. That was a massive project and paved the way for the larger-scale Big Games I’ve been doing since.

1996's Gearheads was co-designed

by Lantz.

GS: How has your past work at Gamelab and POP influenced your work at area/code?

FL: Gamelab has been doing a large-scale, social game at GDC every year for the past 5 years or so, those were awesome learning experiences. And, in general, both Gamelab and POP create a lot of small scale online and downloadable games. These games have to have instant appeal, they have to be accessible and fun to a broad audience of casual players, and they live or die based on their gameplay. I try to apply these same design principles to the games we make at area/code. Balancing accessibility and depth is the goal.

GS: Why does area/code work in primarily urban space? How is it related to game space?

FL: Well, cities are where you find the most people! But we don’t see ourselves as limited to urban settings necessarily. We’re currently in the early design phase of a game that includes cities in it but goes much further, and will be completely global. The relationship between cities and games is complex and fascinating, you can look at the recent evolution of cities in games (Orgrimmar and Ironforge) and cities as games (Sim City, but also San Andreas and Las Venturas). There is a lot of weird and interesting crossover between what architects and urban planners do and what game designers do – structuring experience through systems of geometry and space. We take a lot of inspiration from how skateboarders appropriate urban space for play, and how they look at the city from a totally different perspective. We want to make games that flip players’ perspectives in a similar way.

GS: What influences, either in the game or art world, have impacted your work at area/code?

FL: German boardgames; role-playing games; sports; social gaming (like Werewolf/Mafia style party games); MMORPGs; GTA-style digital urban gaming; Geocaching; reality gameshows like Survivor and The Amazing Race; CCGs, physical-computing games like DDA and Eye Toy; ARGs; LARPing, Military Re-enactment, and other forms of site-based nerd culture; happenings; earthworks; Situationism; Christo; Serra; Andrew Goldsworthy; and many others!

2004's ConQwest

GS: Where does technology fit into the art of "big games"? What new technologies do you foresee working with/are excited to work with?

FL: A lot of what we do is discovering the gameplay possibilities of all these new location-aware technologies that are just now emerging, and creating games that take advantage of the fact that a lot of us are now living with one foot in the real world and one foot in Wonderland at all times. We spend a lot of time “shopping” around for new technologies, many of which are super interesting but are not yet clear about their practical utility. Games are great at inventing utility, at creating problems. We love to take something that does some weird, cool physical world / information space crossover and build a game around it.

GS: Do you feel area/code is aligned more with the video game or the board game tradition?

FL: One of our slogans is that we make games with computers in them instead of the other way around. We like to think that, as computers continue to get smaller, more distributed, and more ubiquitous, and as gaming continues to evolve and grow and mutate, the hard distinctions between videogames and boardgames and sports will tend to go away, and we’ll see all of these things as part of the grand, long-term context of games in general.

GS: In regards to a game like Pac Manhattan, can you talk a little about the transition from virtual to physical play space?

FL: As soon as you take a game like Pac-Man and blow it up to city size you immediately have all these tricky design problems to solve. Many of them are about information–not just how do you track the location of all the players, but even more importantly, how do you represent the state of the game to all the players. So, in Pac Manhattan, the students spent a lot of time thinking through the information management issues: Who knows what when? And it turns out that a lot of what makes Pac-Man Pac-Man is right there–the ghosts have numerical superiority but Pac-Man is “smarter,” and we captured that by giving Pac-Man access to all the information but limiting what the ghosts can “see.” It turned out to be a really interesting and fun part of the game. Another design problem was how to model collision–do you require physical contact or just proximity? And then one of the main things I was most worried about was simply physical danger. I really, really didn’t want anyone to get hit by a car.

Another photo from Pac Manhattan.

GS: Area/code has recently received more press as a marketing company than a gaming company. Is this also area/code's focus? Why or why not?

FL: Yes, a lot of our projects are sponsored by big brands who want to do something other than traditional advertising. They are especially attractive because they are big and attention-grabbing, and public. Unlike a traditional computer game, where you are just talking to the players, with a Big Game the play of the game becomes this visible, public event, so the players of the game themselves become a kind of media that broadcasts out to the rest of the world. And of course, also these games speak to exactly the audience that has stopped watching TV.

GS: Can you talk a little about the connection between "big games" (and ARG's) and advertising? Is the connection necessary, or can/should such games exist on their own?

FL: We are actively working on commercial applications of Big Games in addition to the sponsored and promotional projects we’re doing. Ultimately, we think there will definitely be a market for commercial Big Games that might be subscription-based, straightforward retail, pay-to-play, or some combination of these.

GS: Which of area/code's games do you feel has been the most successful? Why? When a game has dual purpose--marketing and play--what defines success?

FL: Our game ConQwest won some prizes, and generated a ton of what are called media impressions, and in general was considered a big success on the publicity front. But I don’t think any of that would have happened if the players hadn’t been passionate and enthusiastic and driven. At the end of the day, I think the games are most successful as marketing when they are successful as games. You have to have an engaging, compelling player experience in order to capitalize on that for bigger communication purposes. For us great gameplay is the engine that drives everything else.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like