Beyond Machinima: Rudy Poat and John Gaeta on the Future of Interactive Cinema

Visual effects designer John Gaeta, best known for his Oscar-winning 'bullet time' effects for The Matrix, talks to Gamasutra about his collaboration with EA's Rudy Poat on a startling new film using real-time game engine manipulation and AI.

The term "Next Gen" is bandied around pretty freely nowadays, but what does it mean? Some would say that it's a term that loses all meaning as soon as what's part of the Next Generation becomes current. There are those who claim it's all about delivering a higher level of graphic and sound immersion. Of course, there are the gameplay people who want to see exactly how far we can push simulations by using multiple cores to provide better physics and interaction.

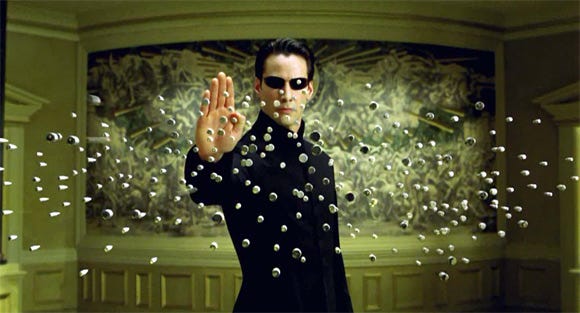

Finally, you have John Gaeta and Rudy Poat - these guys want to get you off of the couch and into an interactive cinema experience, and who better to do it? John and Rudy both worked on The Matrix - John won an Academy Award for his effects which include "Bullet Time," and then went on to work on What Dreams May Come. John is currently working on a few projects and Rudy is a Creative Director with EA Vancouver. We sat down with Rudy first, to talk shop about the new process they've created.

Gamasutra: Can you give us a quick rundown of your project and the technology behind it?

Rudy Poat: Which one? Deep Dark or Trapped Ashes?

GS: Trapped Ashes.

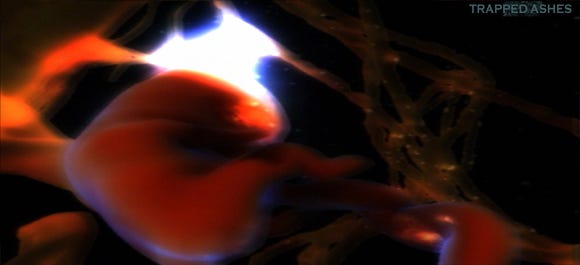

RP: Trapped Ashes was our first experiment with interactive real time cinema. We wanted to do something to deliver frames in high definition (HD) that were ready for film the minute they come out of the box in real time. Compositing and everything is done in-engine. What's cool about the film is that everything needed to be abstract, these soft membrane-like images, and that's really hard to do in real time. Everything looks like Metal Gear or the Unreal Engine now, and we wanted to get away from that look in this movie. We decided to try to tackle it with a real time engine, so we built a way to do those shots.

So, the shots are not only created and delivered in real time HD, they can also be loaded up at any time and you can move around in real time. These shots also run on a server, so on a network, a camera man could log in and film in real time. Another person could log in as a lighter and have him moving the lighting around while the camera man is taking pictures. You can have several people at a time logged in working on the film.

GS: That's a very interesting way to go about editing. With so many people able to log in and modify the film, is there a locking mechanism like the ones used on databases so that one person can use one item at a time?

RP: Only if you run into a limited frame rate. Like, with the machinima stuff, it's a network capable engine so it's collaborative. For instance, one of these shots in Trapped Ashes, we can have three or four people actually collaborating. We could have a lighter, a camera man and an animator. The animator could be moving the fetus, because there's a fetus in one of the shots.

GS: Right.

RP: They could all be chatting with each other on a mic, at the same time, and the camera could be recording all of that data and streaming it straight to film. It's pretty neat. I know the machinima guys are using game engines to make these little movies. They all log in and do these stunts while recording them. We're actually building it that way from the ground up. The big thing for us is the content and not the engine.

Our next project would be something like this, but taken steps further. We're giving it the looks and real time experiences that haven't been seen in games yet. We want to make everything from interactive storytelling, to maybe PS3 online delivery. It could be some kind of online TV show that you could interact with or create characters that would show up later on. We're dealing with getting content together. The engine is the foundation of it, Trapped Ashes was the first test and one of the first times anyone has delivered a real time film that you can interact with the shots. We want to try doing an E3-type thing where we can show the film and then say "why don't you try making the shot with the same database?" That way you could be creating film on the fly. That's where we're going: TV, short films, artsy interactive cinema. It's all about content. We can build the engine again and utilize the parts of a lot of real time tools out there. The thing is how we're doing, putting it together and how we marry that with the content.

GS: The engine that you're using, is it something that you've written or is it just a bunch of tools put together?

RP: It's a bunch of third party tools with a bunch of proprietary stuff that we've created, like the way we do shaders, cameras and lighting. The engine is always changing and evolving. Right now we have a bunch of engineers working on a new foundation. That movie was our first test, so now we're rebuilding it from the ground up.

GS: Streamlining?

RP: Right.

GS: I read that you're utilizing artificial intelligence for interaction. Is that from an artificial intelligence programming level, how lighting reacts or what?

RP: It's actually game artificial intelligence (AI) building and we're utilizing pieces of a game engine. So, we try to make things smart. If we're making a real time film, we want secondary characters to know when to move out of the way. In the case of Trapped Ashes, we have lots of little particles that float around, we want those particles to move out of the way. We want things to be smart enough to do things on their own, like a game, so we use game technology to drive all this secondary animation.

On the set of Trapped Ashes

We want to build a system where we could make something think. For instance, say we make a television show that has twelve episodes. We actually want to build living sets, where a collaborative film team can go on set and record the data in real time. You can have lighters and animators in there. You can also do pre-production where producers and directors can sit around in live chat and play. They can block out where the stuff should be. At the same time, we want this living set with all sorts of AI embedded into things. Where everything looks good, no matter where we take the camera, because the camera knows what looks good. Using neural networks, we can teach the camera to be smarter about what looks good. This way we can start having inexperienced people making episodes and films. They can go in there and start moving the camera around. The secondary characters move out of the way, the lights come on when someone enters the room. Simple things like that. If the whole place is alive and animated with these rules, then you have a way to make content very cheaply.

GS: Yeah, it would cut down on your manpower requirements and skill level hindrances.

RP: Exactly. What's also cool is that you can do things like, introduce characters that were made by the consumer. It's like a big film making mod engine, like the machinima stuff, but we're taking it from the visual stand point that it has to look good. The machinima stuff is fun, but it doesn't look good.

GS: It looks more amateur.

RP: Yeah. You can't make anything professional with it. We want to make sure that whatever we start with looks great. If it doesn't look great, then we'll wait ten more years 'til it gets there. What we've proven with Trapped Ashes is that you can get stuff to look good now; there is a way to do this.

GS: I read that you're currently using Quad SLI machines to do your rendering and run your server. Will this process be useful on consoles as well?

RP: Definitely. It could run on a PS3 or the XBox 360. One of the intents is to run on a game platform. Right now it's geared towards running on multiple Nvidia cards. One thing we're toying with is making an executable from a shot of the film that runs like an interactive game, you can take the camera around, move the lights and do whatever you want. I can send this to a director, to someone like John who's very particular about the way things should be. It can be an executable for the 360 or PC, then he can run it, play with it and hit record what he thinks good camera moves and lighting set ups, and it records it. It creates this little meta file that gets sent back to me, we send it to a render farm with a bunch of Nvidia cards and then we know how to create those shots. There are all kinds of ways to use this and we've been using it. To us, it has to be on a Matrix level and it has to be so visually stimulating that everyone responds to it.

GS: It gets noticed.

RP: Yep.

GS: So you would send that out, they hit record and it saves their actions to a file.

RP: Right, and that would come back to us and we'd render it. The secret with what we're doing is the layered shader stuff. Actually it's a lot of the same technology that we used to layer shaders for RenderMan in the first Matrix movie. It's just layers upon layers, we keep layering shaders on top of each other. Whether it's real time, or two seconds a frame, it doesn't really matter for us. Once we have that meta file, we can give it complete film quality, Matrix level with huge frame rates, and instead of making it real time we can make it three seconds a frame. Now, we have a render farm that we can render out CG film, something like a Shrek level, on eight Nvidia cards.

GS: So you end up saving a lot of time?

RP: Right.

GS: So, you can have it running on a server and have people log in to it, how's it limited by bandwidth?

RP: With Trapped Ashes we had three people logged in at the same time. We had a lighter, animator and camera man in there at the same time without a frame hit at all.

GS: I read that you can use MAYA and 3D Studio with this system. What level of interaction do they currently have?

RP: They're just used for models and textures. Building the assets and putting them in the engine. What we've built is like a simplified game engine that leans completely towards visual quality, interactive television and interactive film making. This is a mechanism for interactive story telling. We're not trying to make games, but that happens on the side anyway.

After getting an idea from Poat about how they made it work, we spoke with John Gaeta to find out why and to see where he thinks it's going.

GS: Do you play games now or are you interested in gaming at all?

John Gaeta: I am not a hardcore gamer, but I'm absolutely fascinated by the game content evolution. I'd say you'd have to put me in the casual gamer column. The understanding of the experience and the underpinnings of the design is something I can see very clearly as I watch my friends play. I've had a lot of experience over the last few years talking with different developers and designers about their quests.

GS: While speaking to Rudy, he mentioned that you guys saw this as a gateway into a higher level of production for gaming cinematics and game rendering. What interested you in that in the first place?

John Gaeta

JG: Basically, to me, there are fundamental characteristics of cinema and interactive gaming that have developed over many years that are very reliable techniques to capture the imagination of the player or viewer. There are attributes and paths of entertainment that have a lot to do with the experience of not being able to control anything, the mystery laid out in front of you, the unpredictably, the singularity of a sculpted vision as a director and writer can lay out. That's really the polar opposite of interactive gaming, and I'm not going to get into that whole discussion because that's happening on the sidelines ad nauseum, in an interesting way. There's a lot of debate and discussion of why interactivity needs to remain in the particular format that it's in because it's about the play and it's about the experience. I feel that's a completely rock solid theory that people put out there. Interactivity is definitely using a different part of one's brain, and it's a wholly different entertainment experience.

I have no interest at looking at gaming and suggesting that story lines can be improved, because that's a completely case by case basis based on what the concept is and how it was executed.

GS: Sure.

JG: The same goes for film. We all know that there are remarkable films that change your life and there are films that pass you by and you don't care. It will always be that way. That's the nature of film. I'm curious about several things. One, from a technical point of view, I think this is going to be of great interest for film makers as it will give them access to ideas that they could never achieve through the process of pre-visualization.

In the last few years, this has allowed people to try things that were previously unthinkable, because it allows you the higher understanding of simulating your film in advance. You suddenly receive this wisdom that was impossible to imagine your way through. Pre-visualization, to me, became a gateway to higher concept in cinema. Essentially, it is a simulation, and in the last few years we've gone from doing it in a laborious hand-sculpted way to what, I believe, is taking hold now is greater and greater reliance on more sophisticated simulations to allow you to visualize cinematic content.

The strongest linkage between cinema and games in terms of partnerships between the two industries and artists has to do with visualizing content per se. The deeper we go into this, the more we will align the platforms, methodologies and artists behind them. It's happening, we see it happening, and we all have a lot of associates that are able to pass back and forth between the two industries and actually do quite well. If this change continues at the pace its going, coupled with the fact that the audiences for film and games are changing quite a bit with the new generations growing up on interactivity and are becoming addicted to being able to access more from their entertainment, it's infinite exposition.

The problem with film is that you can never develop the characters deeply enough, or find out enough nuances about the world in the setup. You potentially become frustrated before they wrap it up in two hours, or nowadays ninety minutes. The screen time is definitely creating the risk of an empty feeling at the end. Like, I didn't get enough depth out of that story experience. Games allow you infinite expository capabilities, and that is possibility the strongest characteristic of a game universe.

Where I'm coming from now is [I'm] watching, and in some ways helping to push, the trend towards an alignment of applying simulation of both game and simulation content. The technology used for it and the artist used towards it. I want to unify the conceptualization of film and game in the same moment, and to allow the execution of the final rendering of certain cinematic content within the same platforms such that once that is working at a quality level that will pass muster for a wide screen high definition theater system. The idea is that one would have access to that exact same content for an interactive experience to create a much deeper, immersive experience to have at the periphery of the director's vision. To step back and try to simplify that statement: let's say a director sculpts a scene and you're riveted by it in the theater experience, and you've experienced it in the way they wanted it seen. Then, here's the opportunity to revisit that exact same scene. It's a three dimensional interactive mirror of that exact same content, assuming that certain things can be achieved like chronological time and it's not so abstract in its editorial construct. You know what I mean?

GS: Yeah, I think so.

JG: So you can actually experience that scene and widen the ability for the audience to see everything that's happening at the periphery of that scene, the environment of the scene, potentially embedding expanded nuance and mystery in these scenes.

For example, you could have a scene with two people and believe you've seen everything you could in the movie experience, but at that precise moment in the interactive version of that scene there could be another character that you didn't know about, watching. Thusly, you could create another whole thread of the mystery that wasn't known at the time of the movie screening and you could expand upon that thread. Or, that scene, which would have to be a virtual construct of some sort, could be a portal to the gameplay universe. Outside of those doors, play could happen in full chaos mode. Essentially you take that moment, and turn them into nodes within an interactive format. These are nodes that you can expand exposition and then exit, if you will. They then become gateways.

The time frame when something like that will happen is essentially when we can achieve exact match fidelity between what you would need to put on a wide screen experience and the best you can do on a game console or on line experience. As we watch the state of the art in real time graphics, we can see that we are definitely getting closer and closer to being able to do a nice job on an animated movie that can be re-visited in match fidelity as an interactive experience.

GS: So, you could experience each scene from different angles, you could move it around or whatever you like with real time rendering.

JG: Well, yes, the simple first step is sort of like Bullet Time again, right?

GS: Right.

The 'Bullet Time' effect left a lasting impression on viewers of The Matrix.

JG: That's the surface, that's the first go. To me, what's much more interesting is that the universe is dynamic. Here are a few examples: yes, you can see it from any angle perhaps, but embedding things that one never knew was there in the first place. So you solve the exposition problem that films tend to have. Additionally, you can create crossover dramas, dramas that cross over the spine. It's as if you're looking at a movie as a spine that runs through the game universe. It sits there like a dynamic sculpture in the center of this game universe. If you choose to observe or pass through the film, you can, but the universe is still there as any game universe would be.

I find that really fascinating because it gives you a lot of different options. You can be a voyeur, cross over the spine or build your own crossover thread, for those who are into Machinima interfaces or expanding worlds. That way you could have an influence.

Another example that I think would be fascinating, is that in the year 2006 we can only really be thinking about these things in terms of an animated feature, but we all know that it's only a matter of time until we are able to do some virtual cinematography inside of a game system. Essentially we'll be able to create a hybrid environment using some of the techniques used in film. That's all starting to filter into games now, and it's adding a heightened sense of realism. Even importing moving, high def environments like a seascape that changes into something I can interact with at a certain distance. There are many interesting "mashings" that are about to happen over the next few years.

You could look at a film five years from now that will have all the dramatic climaxes and arcs, but is a passive experience. Another way to look at the semi-interactive mode is that we could construct a movie in a way that the world environment that surrounds fixed scenes, like two actors talking, is a busy city. Suddenly there's a car accident behind one of them, if we constructed the world behind the acting as a dynamic simulation then that car accident wouldn't always happen. That would make the movie different every time it's viewed. It's full dynamic cinema. That's a step between passive cinema and what I was just describing.

JG: There are degrees of semi-interactivity leading towards full interactivity, which is the pure game. I believe that people are inadvertently, some of them on purpose, on a pathway where some of their innovations and creations could become very useful puzzle pieces to make these incremental steps between film and games.

The cineractive is a very simplistic passive adjunct to a game, but if you step back one layer it could be an interactive cineractive. The cineractive can be photo realistic at one point and the game could have a match fidelity to its cineractive and you're almost to what I'm talking about here. It all has to do with whether you can have precise match fidelity, so that the experience is contiguous and immersive. In a way it lends itself more to games that tend to be more ambient, and less information heavy. Shadow of the Colossus is a good ambient, cinematic type game. That's the type of game that would interweave in this way if we chose to do that.

Leading back to my experiment with Rudy, which was a really small project, is trying to get people to imagine that there is a market for hybrid formats like this. It's going to happen, because we see all the machinimist experimentation. The new generation wants more interactivity out of their story content but we can't do that in a way that breaks the fundamental, structural needs of storytelling. Every time we try a chaos story mode, people feel that it's too open ended and it doesn't have the emotional impact or weight as if someone has weaved this labyrinth for you to travel with a destination in mind that isn't expected.

It's like knowing how the movie The Others ends before you get there. I feel that as the new guard comes into film making and a lot of them now have experience on the gaming side, I believe they'll begin experimenting. The first tier will be visualization as a technological link that overlaps all the right people and tools for the first steps.

GS: Ok then.

JG: How's that?

GS: That's great.

JG: You've just experienced the classic John Gaeta spiral out. It's my favorite way to talk. I apologize, I tend to do that. I kind of let the idea ravel out.

GS: Oh, no, really, I'm the same way.

JG: Some people think I'm an engineer, but I'm not an engineer at all. I deal a lot with technical concepts. I really like re-arranging building blocks. I like to take very bright folks and pool them together. I give them a slightly augmented goal, thinking that they can take it somewhere. That's why I'm less qualified to talk to you about the mechanics of Rudy's materials than what objectives I've set out for him because I knew he was capable of certain things. I've known him for ten years now.

The cinematography and immersion of Sony Computer Entertainment's Shadow of the Colossus is an inspiration to John Gaeta.

GS: You mentioned Shadow of the Colossus earlier, and I know that with Bullet Time you've inspired numerous game mechanics over time, have any games inspired your work?

JG: Oh yeah. Yes. I'm not sure how to quantify this, I'm not a hardcore gamer, but I obsessively watch games and people making them. I've gone to GDC the last six years. I've met many people who have made games and I've had friends who have gone over. I've had my friends take me through games, but I'm kinda feeble when it comes to controllers. That's created a little inhibition in me, a little bit, to get into certain games too much.

That doesn't mean, though, that I'm not observing the action. I'm very fascinated with algorithmic action beats and evolving algorithmic action beats. How people create climax, how you build your way through achievements and how you die, live again and pass your virtual self to a deeper place. It's a very interesting concept. To me, it's the staging ground for virtual reality in general and how you can think of yourself as an avatar that can live and die several times over.

JG: In terms of games that are inspiring, it depends, different things in different games. I could run off a few games I think are fascinating.

GS: That would be great.

JG: As far as story heavy games go, I'm fascinated by the Metal Gear Solid franchise. That universe is unusually rich. I'm also curious about the team who made Resident Evil 4 because they have a great understanding of atmosphere. The Myst series has innovative weaving of passive and interactive structure and is an excellent ambient play experience. The Black & White Series and Peter Molyneux's God game concepts in general, playing God. ICO and Shadow of the Colossus, both are very cinematic and immersive. You feel like you're inside a movie. The Final Fantasy series redefines the Japanese visual aesthetic, and has an expansive universe. The Half-Life series is a great science fiction concept, with excellent suspense.

With action, I'm a fan of the Mech Warrior series. I love the shock and awe style robotic destruction. Soul Caliber has really cool characters and surreal combat. God of War is completely psychotic, violent and cool. On the strategy side of things, I'm also pretty fond of the Age of Empires and mythology games because they make wanting to learn classic literature and history fun. I also enjoyed the Sims, but I'm really excited about Spore. I think it could be the Citizen Kane of gaming.

I'm also interested in games that are physics based. There's a variety of interesting car games out there.

GS: Like Burnout?

JG: Yeah, like Burnout, Forza Motorsport, Gran Turismo or Need for Speed. I like all the car games because they're interesting, inspiring and free. For example, if I'm working on a movie, and I can't tell you what I'm working on, but it'll make sense of this statement: if you look at car chases in movies, which is what I'd do if I'm going to be working on a movie with a lot of car chases, finding out what works and what doesn't. You know what? I think that those times are kind of passing us by where that would be our references.

Need for Speed: Underground

Again, the current generation, unbeknownst to many adults in the film industry, is being completely infused with a higher order of action with some of the gameplay. Driving games, robotic battle, all of the different topics at hand, can be done much more freely. You can create a more visceral interaction, and in doing so have begun to pursue fantasy mutations of things that can only be done in a physical way in the movies. They're completely virtual.

You know, when I view cinema, play games or watch people play, I always prefer for it to be on the widest screen possible and it must have surround sound. I firmly believe that the objective environment to have, and will be had within a number of years, is a dedicated sound proofed room, let's call it a "Boom Room," with a hyper broadband tethered HD projection system (capable of optional stereoscopic) no smaller then one full wall up to 12' in diameter (but someday should be three or four walled) and a deafening surround audio system, Holophonic if available. Even if the graphics are not photo realistic in nature, the highest possible resolution at sixty frames per second can induce heightened psycho-physiological experiences. The "Cadillac" boom room includes a pure oxygen system as well. Those with serious cash on hand should keep a therapist on tap between session to convince them to keep going outside and processing reality in its raw form.

We all know the moment that the only thing that limits you is conceiving it in the computer, even if it looks very minimalist, yet the idea of it can be delivered at some quality, at that point it's all about the experience of the action. I would rethink car chases, car stunts, everything to do with cars, space ships or robots by way of the type of experiences that some of the games are delivering. The audience is most likely coming into a movie about cars or robots having already witnessed completely outlandish things that no movie has delivered yet. I think that's the imaginative frontier, and it's much wider now that it was. It's not necessarily delivering the sharpened, sculpted super-punch that a movie can, but there's certainly forays into different genres are being pushed out way faster than they are in films. I observe games obsessively for different clues.

GS: The youth these days are completely inundated with media, and for many kids that's all they're interested in.

JG: Yes, interactivity is definitely an addictive force that engages your brain in a different way and can expand your mind, or it can do the opposite. Either way it has a far deeper reach. The question is: how do we actually fuse the best qualities of game and film into a hybrid? I think that could be a phenomenal third place that not everyone has to pursue, but there's a whole new order of entertainment experience that can come out of it.

GS: I was talking to Rudy and he mentioned that you can have several people working on a project at once. Did you guys do that with Trapped Ashes?

JG: Rudy has built it that way, but I've only ever done that with just him. The real gist of it, what's meaningful to me as a creative, is that I can compose, or very rapidly keyframe, at HD resolutions. Of course, this is Rudy's territory. We're trying to work out a new way to visualize our film content as fast as possible but at also as high fidelity as possible so that we have an understanding of what we're gonna get at the other end. You're accustomed to some of the shots I've worked on having hundreds and hundreds of layers, this does not. This is much more minimal by comparison. It really only features one real element, the baby, and it's environment, which is procedurally generated, is less important than our composition on this one element. We've chosen what I consider a baby step towards a process in which we conceive, animate, compose and render as simple as we possibly could just to make it to the other side. Being able to output to film alone was a Herculean achievement on Rudy's part. That alone was something we weren't clear that we were going to be able to do, we were prepared to do it more traditionally.

Trapped Ashes

It's not a very big project, probably 20 shots or less, high teens, of a very reasonable, straight forward moving camera composition. It had some beautiful cameras and lighting, but in general we're not talking about twenty cars and stunt guys, right?

GS: Right.

JG: He and I are basically more along the lines of real time composition, simple animation, like the limbs of the baby will twitch and things on that order. For us, it was a conceptual starting point for doing that on film.

GS: So you see this cutting down render time?

JG: Oh, of course, absolutely. It's the question of how many elements at what quality level for what purpose of visualization. Is it a subset of a larger project? Is this what quality level you'll be outputting? The reason, to go back to the beginning, which is why I said all this, that I find this topic so interesting is that we're inside a womb. It's a very fascinating universe to begin with. Then we make these scenes where the baby twitters as if it's aware of the outside world, and whether it's reacting to sound or whatever. It's this freakish commentary on whether the unborn child is aware of its outside universe or not. We found it interesting from a concept point of view and we thought "what if we made this content in a way that later people could move around this environment in the exact same quality." Along the way we decided to build in some additional AI attributes like if the camera gets to a certain proximity there's some reaction, or with the outside world you can control the lights. Essentially, though, it's the exact same content that was put to film at one point, looking the same but navigable.

GS: Ok, and I…

JG: How you feeling about this conversation so far?

GS: I think it's fascinating.

JG: I'm just trying to gauge on whether or not you think this is interesting or if you think I'm full of it.

GS: Not at all.

JG: To boil it down, right, because I've done things large and small, what I've learned through the years is that when we get into real time cinema, navigational cinema and the future of next generation games. Those are lofty phrases. You potentially get yourself into a position where people think "I don't know if we can pay forty million dollars to make this game. First of all we don't know what real time cinema is. We don't know what navigational cinema is. We don't know if people will like it. We have no idea." Questions abound. The type of franchises, companies and developers that we want to make these games, like the Half-Life guys or whoever you like, you have to think it's a difficult business decision to make because it's so large.

GS: It's risky.

JG: I've been there with film, I've been in the exact position. Should we make all virtual humans and environments to do the next exponential leap of Bullet Time? Is it worth it? Is it not? Why bother? Having gone through some of those painful decision-making times, I realize that the best thing to do for trying to birth a sort of hybrid medium is to try a bunch of small experiments.

People in the film and game industry, and I know some who definitely are, should engage in small experiments to prove out how engaging this idea could be. I think that the machinima guys are in some way a branch of this, it's not what I'm aiming at, but it's a branch. Those kinds of small movements are of great interest. People need to do this right now. Technically we're a couple of years out. That's not long at all, literally a couple of years out. There are enough people working on this project from different angles to conceive serious projects in this area. Whether that's real time episodic content for television, something happening on line or games and movies that have navigations nodes. All of those experiments fit nicely in a three to five year time frame.

In a nutshell, our experiment was to take it from conception to a screen. Ours did, it was in the Toronto Film Festival, so it made it all the way out to a wide screen. I don't know if the movie will make it into theaters exactly, but it was satisfying to make it to the screen.

GS: Rudy mentioned Deep Dark, can you talk about that?

JG: I can't really talk about that in detail. How can I put it? It's fragile and fertile.

GS: Well, we don't want to screw that up. Other than Deep Dark, is there any other projects you're working on?

JG: I have another project; I directed another short film. It'll come in under and hour. It's called Homeland, and I shot it in HD. It's a live action anime shot in Tokyo. It's all digital effects and entirely shot in Japan. I have a real fascination with the potential of a live action anime.

Homeland

GS: It's stylistically very interesting.

JG: I think so. It was a labor of love. It's a project that allowed me to collaborate with people in Japanese cinema, concept guys that I've only really just stolen their work. I've been so influenced by them that I wanted something more direct. It was really awesome to work with those guys.

GS: When do you think that it will be available?

JG: The live action portion without the anime may get released ahead, maybe by spring. I'm waiting to see exactly what the time table is with the anime bit. We're planning on doing some episodic stuff. We have some very different spin away content pieces, interactive, short form bits of content that are purely distributed over the web also. I can't really explain it better than that. It's experimental web stuff. It's going to be a pretty good interactive experience, I think.

GS: Sounds great! Thanks for taking the time to talk to us.

JG: Thank you for your patience. I'm glad you guys are interested in what we're doing.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)