Believing is seeing: Orwell and surveillance sims

Osmotic Studios’ Orwell has players snooping through IM chats and blog posts, gathering data to assemble a profile of a suspect. The chilling consequences of your choices are made abundantly clear.

What do people think they know about you on the basis of what you post to social media? Being the target of online abuse provides an answer; I’m on websites where literally dozens of my tweets are hyperlinked and framed as evidence of this or that deep, corrupt association with some random person. My silly, shallow repartee with a dev becomes proof that we’re all but blood bound conspirators and best friends.

What we call “evidence” in such cases is really a veritable Rorschach test, susceptible to wide interpretation; we see what we want or need to see. Given the point-and-click nature of such stalking it was only a matter of time before someone made a game out of it--enter Osmotic Studios’ Orwell.

Here you play not as a random online harasser but one given a certain amount of authorial power by your government. You’re literally one of a million, beating out many other applicants from the general public to access a virtual tool that allows you to draft criminal profiles on the basis of snooping on IM chats, blog posts, and the like. Think of it as being a Stasi-style civilian informer with access to an app for that.

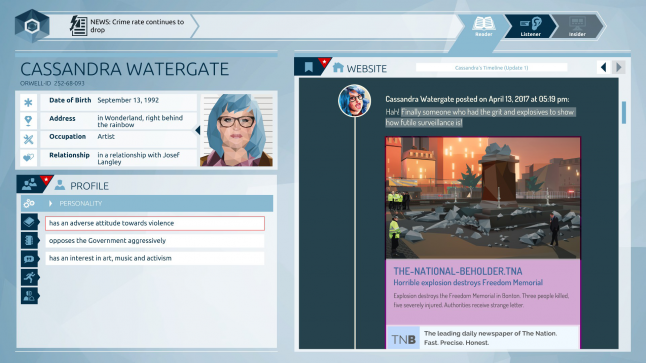

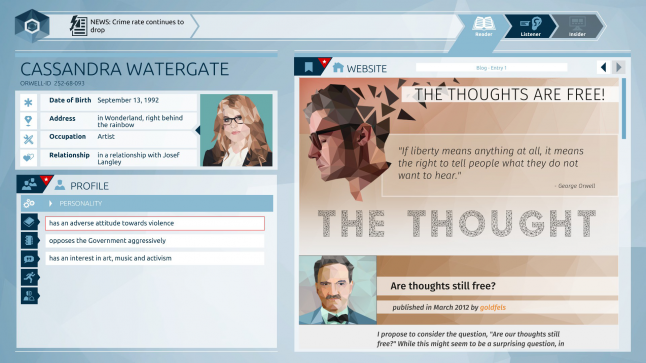

In the wake of a bombing at a public square that killed three, you are tasked with researching the prime suspect: Cassandra Watergate, a blue-haired woman with a short police record who left the scene moments before, according to the arsenal of CCTV cameras around the plaza. Gameplay is simple: guided by your handler, Symes, you click and drag “datachunks” from the various documents, webpages, and chats you view into the Cassandra’s profile. Symes only sees what’s in the profile, giving you wide latitude to construct the person national intelligence will come to know--irrespective of whether she bears any resemblance to the actual human being.

This is epitomized by “conflicting datachunks”--bits of data that can tell two completely different stories. Do you use a fight between Cassi and her best friend to “prove” their relationship is over? Or do you emphasis an earlier, friendly exchange? This is, essentially, how choice is exercised in the game and how you shape the unfolding story. You look at Cassi's social media presence and decide what it means. Is she a young woman trying to find herself or an aide de camp to terrorists?

The press have access only to the first “day” of gameplay at the moment (there will be five days in total), but what’s there makes the chilling consequences of your choices abundantly clear.

In a finely crafted moment, you’re spying on an IM chat between Cassandra and a friend when the police come to take her away, after Symes excitedly decides to act on your information. Seeing each text bubble pop up was like watching a countdown clock I couldn’t stop. It’s too early to say whether Orwell will have an option to play the game in windowed mode, but the full screen experience felt essential to its unsettling immersion. I felt cold as I watched this happen, watched my actions destroy someone’s life.

The game interface is perfect. Just as with Moon Hunters and No Pineapple Left Behind, which I discussed in my last column, Orwell is uniquely suited to its medium. Gamifying surveillance, with all the dissociative distancing of both the medium and the Internet at large, putting you at a safe remove from the consequences of your behavior, is brutally apt. Orwell is making an extravagant point about state surveillance and the powers we’re allowing world governments to arrogate to themselves, but its choice of “protagonist,” the random citizen drafted in to spy on her fellows, is what makes this even more unique.

You’re not playing a Man in Black who lives and breathes the life in shadow, but, well, yourself. It puts the lie to the utopian ideal of “sousveillance,” the idea that ordinary people can avail ourselves of techno-snooping tools to act as a check on the powerful. Our judgment is no less fallible, no less prone to heedless destruction. Our dystopian future may not be the uniformed powerful against the masses per se, but the masses being drafted into oppressing each other using the tools of online surveillance.

Orwell can feel a bit heavy-handed at times; it is a world where, at least at first glance, free speech versus state security is the overriding political issue animating The Nation; it feels like an almost sterile world, but perhaps that’s what it’s meant to look like behind Orwell’s deadening interface. In leaving behind all other politics (aside from a subplot about an Iraq-style occupation of another country by the Nation), the game does have the benefit of a tight thematic focus, and yet there are so many opportunities to explore issues like racial and religious profiling that imbricate with our bristling securitized age. There’s still four fifths of a game yet to be seen, however, and so I’ll reserve final judgment until a complete build is available.

What’s here now is a game that, so far, uses its medium to bone-chilling perfection. There are shades of the heartbreaking German movie Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others) where a more old fashioned Stasi colonel, responsible for monitoring the bugged house of a playwright, becomes more involved in the lives of the people he spies on and tries to use his godlike powers to protect them from the wrath of the state. It will be intriguing if Osmotic takes the rest of the game down that path. Symes can’t see what you can; will you have the opportunity to throw the Nation’s spy agency off the scent of people? I certainly hope so. In the demo there was no way, sadly, to avoid Cassi’s arrest, but you can alter its context. If subsequent “days” take that a few steps further, I’ll be very impressed indeed.

***

Our bitter vengefulness on social media, something I certainly don’t absolve myself from, is something that can be weaponized by any kind of agenda--be it emancipatory, reactionary, or, indeed, a government’s. We know, for instance, that the Russian government has actually employed “trolls” to comment on news articles and to harass political opponents worldwide; Donald Trump’s presidential campaign all but relies on an army of 4chan meme spewing alt-right trolls online who routinely harass journalists; a Hillary Clinton PAC employed people to harass doubters with campaign propaganda.

A game needed to be made about this mass mobilization. In an age of panoptic online life, we are being watched. By each other. “Big Brother has arrived--and it’s you,” reads Osmotic’s perceptive tagline. What happens when that capacity, to snoop, judge, and harass, becomes an everyday weapon of governments? “Orwell” seems like a quaint name for it; this is something else entirely. Not simply being oppressed by the state but fully assimilated into its workings, with shattering consequences for truly free speech and thought all around.

For my part I’ve also been the perpetrator of misinformation based only on what I see on social media, failing to see in heated moments that a tweet or an internet comment is the tip of a very deep iceberg. What if that blinkered judgment were harnessed by more traditional authorities, at last merging the structures of formal and informal power?

Thinking on the outcome of such a sinful marriage leads me right back to my own experience with the tweet-archiving crowd who assembled their crowdsourced “evidence” into a collage bearing only a passing resemblance to me. I sometimes wonder what I’d say to that Katherine Cross if I ever met her. A prayer, I think. “May our surveillers have mercy.”

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)