Behind the japes and jokes that power Xalavier Nelson Jr.'s games

Strange Scaffold founder Xalavier Nelson Jr. breaks down the creative process for his games with exceptionally-long-names.

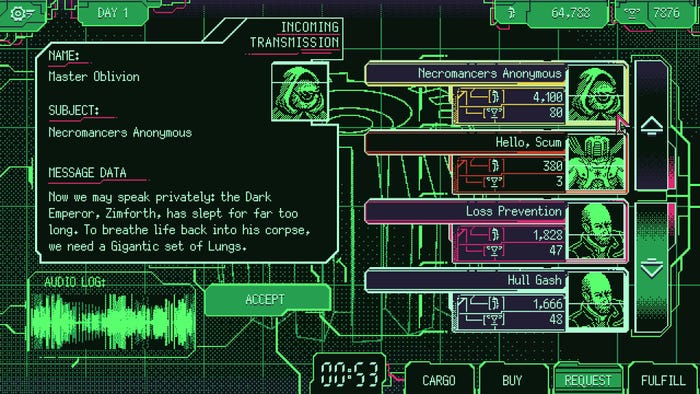

Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator. An Airport for Aliens Currently Run By Dogs. Can Androids Pray? These are some of the games you'll find in the portfolio of Xalavier Nelson Jr., a Texas-based game developer who now runs the game studio (and now publisher) Strange Scaffold.

What they have in common—besides some eye-catching names—is are a series of internally consistent worlds that let players dig their hands deep, into their interactive systems. Whether it's with his collaborators at Strange Scaffold or partnering with other designers like Nat Clayton or Jay Tholen, Nelson brings a madcap, constantly escalating energy to his work that sometimes feels like a comedy bit gone way too far.

But not in a bad way—just in a way that the bit has now grown up, gone through an awkward teenage phase, and has settled down with a partner and kids. Then it's had a midlife crisis and is out the door again.

There are plenty of weird, zany game creators out there, but few who can keep pace with Nelson's commitment to uh...commitment. From Kinect functionality to Pokémon Snap-style alien adventures, Nelson's wild scenarios come from a strikingly sincere place.

It's always worth taking time to talk with developers so able to put their creative influences out in the open—so we sat down with Nelson to jam about what makes his games tick.

Exactly what it says on the tin

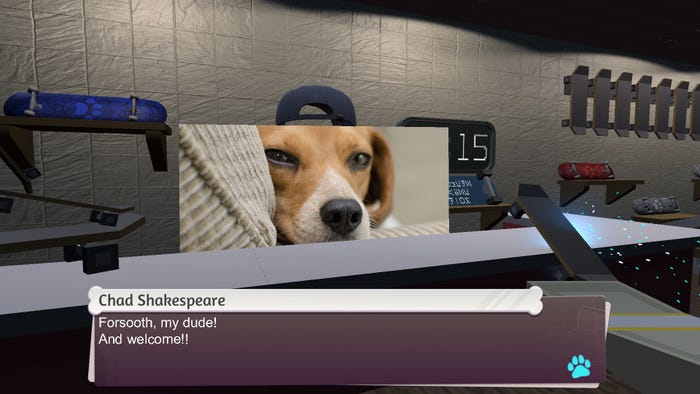

You may have noticed that Nelson prefers working on games with eye-catching, evocative names. Some, like An Airport for Aliens Currently Run By Dogs, come off as fully literalized versions of those single strings.

It's specific, and Nelson explained that specificity sits at the heart of a lot of his design decisions. He enjoys making "good" games (who doesn't?) but is downright feverous about making games that reach people in "very specific" ways.

"That core ability to communicate something specific—not even attached to yourself, but the world that you're building—that is lost when you lack either capability, the empowerment, or the context to be able to embed that kind of vulnerability in your work."

Making games that are "specific" opens developers up to "not being liked," Nelson—and it's understandable that not every developer wants to be that open. But in Nelson's mind, "it's important to good art, and to existing."

How "specific" does An Airport for Aliens Currently Run By Dogs get? If you've played it, you know this is a game about navigating airports, where the player waits for and inevitably takes a flight. Flights are often scheduled literal hours after the player gets a ticket, so they're free to wander the airport and find ways to pass the time (again, literally. There's some temporal mechanics they can access).

They can also choose to not do such a thing, and just wait at their gate for the full time. They can even miss their flights, but no matter what, they can turn around and get another ticket from a dog stationed at the departures desk, ready to send them off on their way again.

A dog, running the airport for aliens

"You could rightfully call that tedious or say that actually can't capture the conceit of the game. But the entire point of the game...is the idea of you being a traveler in a fundamentally joyful universe at the end of the world."

This brings us to another of Nelson's methods for thinking about specificity: that it's a tool for building fully coherent worlds with internally consistent logic. "I believe in the cohesion and the intent of the world over almost anything," he explained.

Well not quite anything. He still wants to make games that are fun and accessible, but the path to those two outcomes is through incredible intent. Nelson prefers design decisions in games that seek to reinforce their perspectives—that help players change their thought patterns to align with how a game's world operates.

His personal example of this kind of design in big-budget games is Kojima Productions' Death Stranding. He also chases down niche games like the Def Jam series and celebrates them for chasing the same specific visions. "I increasingly crave in the art I pursue these days—even for something to bounce off of, because that means something was said here," he said.

"It's not that it was necessarily a political statement or anything else, but simply that the creator swung for something, and I got the opportunity to react to it in a human way. That way we get to [reach people], regardless of the time in which it was created."

There is a bit of a political statement in An Alien for Airports Currently Run By Dogs: dogs don't know what capitalism is, so they can't recreate its highs and lows when running an airport. They'll hand you tickets because they don't need to extract value from their existence.

It's a political statement insofar as...look, dogs don't care about capitalism. We all know this. We mock them for being distracted by balls and treats. And yet their attitude can be inspiring in imagining a "kinder world," as Nelson describes it. "That idea doesn't land unless you are confronted with systems that allow you to view their perspective and how it differs from our real world in that context."

That's why Nelson lets players miss their flights, just how they might in the real world. If a player doesn't board in time, their boarding pass literally goes up in smoke. They can approach a ticket counter, request another boarding pass, and the dog will hand one over. It'll hand 50 over. It'll hand however many over because it doesn't care, "and that interaction," Nelson said, "means nothing in a world in which you don't actually have to take that flight, and which the possibility of missing that flight isn't present."

A Christian background to draw from

I first read Nelson's enthusiastic writing when he was a teenage writer singing the praises of Dropsy. Dropsy came from an indie development team led by Jay Tholen (Tholen and Nelson would later collaborate on narrative elements for Hypnospace Outlaw), and some of Nelson's praise for the game was rooted in his personal faith.

Nelson is Christian—Protestant, or some variation of Protestantism, if you'd like to get specific. He was raised in Evangelical circles, but shrugs off most of the distinctions in our conversation, less interested in identifying a "right" kind of Christianity and more passionate about translating what his faith means for himself as a person and as a creative.

Nelson is one of the few developers I've interviewed who will openly connect his religiosity and his work as a game developer. That's not surprising if you've played some of the games he's worked on; Can Androids Pray signals right off the jump that it's a literally meditative title. It is surprising to meet a game developer who's able to link the two worlds so plainly.

Trying to unpack the link between video games and religion is tough. For a mix of reasons, the video game development world is a very secular one. Religious influences are found everywhere in the art direction and mythologies of different video game series, but it wouldn't be unfair to call much of that window dressing at best, occasionally gross appropriation at worst.

Either because of a consistent worry over controversy or a slightly outsized representation of secular and believing game developers in the industry's ranks, personal expressions of faith in any religion are few and far between. Nelson is nonplussed at that fact—right when the subject is brought up, he points out that Christianity (and American Christianity in particular) have "deeply and intentionally harmed people."

"It's very understandable, the reluctance that exists within—seeing Christian creators express [their faith] in their worlds, given the many harmful examples that exist of it—or just poorly produced examples. Examples that don't exist as well-made art, but of Christian art, and the fact that it's Christian is what gives it the redeeming value."

He paused here, seeming to weigh how hard he wanted to swing his next sentence. "If you wanted to get spicy, we could apply that to atheist art...that exists [just] for the sake of saying 'fuck God.'"

To make sure Nelson's point is clear, he frequently referred to his "nonbelieving friends" in the rest of our chat. He seemed enthusiastic to build relationships with atheists and agnostics, and more critical of those who use atheism (or any other faith) as a cudgel or platform of superiority.

Long ago, the great prophet Hank Hill warned us that American constructs such as Christian Rock would not serve to Christianity better, it would just make Rock and Roll worse. Nelson seems to follow a similar philosophy with game design, explaining that there are biblical principles to bring to the world of interactive play, they just probably aren't the ones you're most familiar with.

"The way my faith affects my work is that I believe, first and foremost, in treating every human being and living soul with not just respect, but a love and recognition of their existence," he said. "As for how that affects the internal content of the game, there's all these little touches and small ways in which it can crop up."

Nelson stressed that this isn't about exercises in morality "My faith doesn't tell me to be a good person, it drives me to discover as many different manners and perspectives and what they can mean," he explained.

When Nelson is building the ridiculous worlds of his games, he says that in the back of his mind he is contemplating the absolute truth that God, Heaven, and Hell all exist in his cosmologies—in conjunction with the absolutely bonkers settings that manifest in his work.

Reconciling the presence of divinity with strange supernatural vibes is a deliberate act of reconciling the ugly pieces of the world with the better parts. Nelson sees love and empathy—not dogma—as the tools of that reconciliation.

There's astound sincerity in Nelson's perspective, but also mischievousness. I dropped a baldly blunt question to try and learn about his other biblical influences: "What is fun about Christianity?" I asked. Nelson's talked about making fun games, and as a more secular (and Jewish) person myself, I don't always equate Christianity with "fun."

"Well where's the blue shell in the Bible?" Nelson shoots right back. We giggle a bit at the gospel of rubber-banding before he steadies himself and leans into my query. "I think the thing I find fun (and terrifying) about Christianity is the idea of an evolving relationship and scope of knowledge with a personal God," he said.

"The idea that he made the entire universe, orchestrated human history, and has overseen US—has watched us destroy ourselves in a thousand ways over time—and given that entire scope of knowledge and power, that he looks at us specifically, and cares."

He paused. "That's fucking terrifying."

Grappling with the weight of that fact alone might border on a contemplation of cosmic horror, but Nelson also describes it as a necessary task when reading the Bible. He criticized efforts to sanitize the Bible (especially for children), calling out that entire sections are about its protagonists doing horrific things—and also things that are hilarious, weird, fun, and relatable.

"Recognizing all pieces of that as part of a wider tapestry is really exciting to me," he said. Gazing deeply at the parts of the Bible that have "had their edges filed off to send a clear message" helps Nelson grapple with the "knot-filled" human ways in which people have grappled with the terrifying knowledge of God's awareness, and become their own kinds of heroes or villains.

Wrestling with those concepts—divine knowledge, and how humans react to it—is an engine that Nelson reaches to in perfecting his art. There's more practical fun to be had too. He jokes about making memes about Biblically accurate angels, or dropping Biblical turns of phrase in his dialogue. "That acknowledgement of the supernatural—and discovering new ways it can evolve or impact the way I see reality—is genuinely fun."

"Sharing that even with my unbelieving friends is one of the great joys I have. Because if I'm going to believe in a dead book with a dead god, I wouldn't really see the point of living."

A boiling point in design

Nelson's design philosophies trickle down into the language he uses—both in his games, in social media, and conversations. While meeting up at DICE, I shot him a message letting him know I was going to be a bit late. He playfully replied "already boiling; furious."

In closing our conversation, I paused to ask about that word choice. The notion of Nelson sitting in a Las Vegas hotel, turning beet red, emitting a strange bubbling sound got a giggle out of me as I exited a nearby elevator.

Here, specificity reigns again in Nelson's head. He explained that his love for specific, evocative word usage is what's behind this peculiar vocabulary. "The word 'flesh' is great," he pointed out. "The word 'meat' is great—depending on the context on which it's said."

"The wrong word in the right context is one of the most beautiful things we have in spoken communication," he said. It's a sentiment that's nicely explained my time with Nelson and his games—wrong ideas, wrong words, absolutely the right context.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)