Behind Demonschool's eye-catching design choices

Necrosoft Games' Demonschool is a turn-based tactics game like no other. We talked to game director Brandon Sheffield about how it came to be.

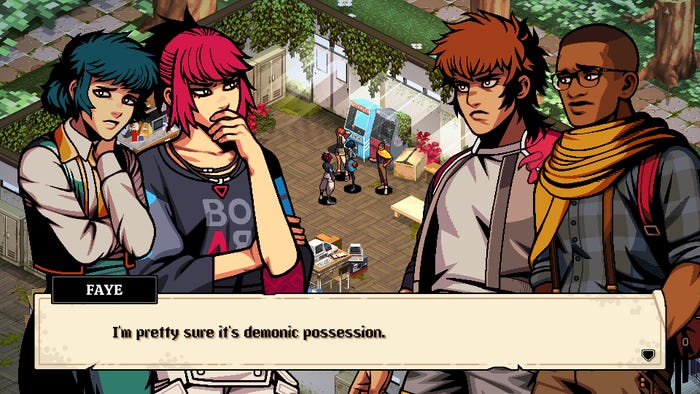

In a genre as old as turn-based tactical RPGs, it takes a lot of creativity and forward-thinking to make something that feels fresh. Right from when it was first revealed, Necrosoft Games' Demonschool has been a feast for the eyes and stimulating to the brain.

The studio's affinity for candy-colored fantasy worlds and tweaking with familiar game mechanics are all there on the surface—but it's new flourishes like an unsettling giant skeleton and a focus on character fashion that might make this game a must-play in 2023.

Necrosoft Games was founded by Brandon Sheffield—a longtime friend to Game Developer because well, he used to work here. He used to be editor-in-chief of Game Developer Magazine and a senior editor on this recently-rebranded website (you've also seen his name pop up here and there in the intervening years, and he helps run programs for our sibling organization Game Developers Conference. Go read his still-relevant piece on dirty coding tricks!)

I don't get many opportunities to talk to former colleagues about what they're working on next, and Sheffield's journey from games journalist to game developer was buoyed by his passion for '90s Sega titles and hard-learned lessons from shipping games on killed-off platforms (RIP Oh Deer!).

Sheffield's had a lot to say about how developers can foster creativity in their work over time, and since I've heard him ramble about Demonschool development challenges over the course of its development, it was a rare chance to ask him about Necrosoft's process. It's the kind of conversation you can't always have while previewing an upcoming game, and Sheffield had plenty to say that could help other developers.

How Demonschool is putting a new twist on tactics

Some of Demonschool's design sensibilities will be familiar to fans of Advance Wars, Final Fantasy Tactics or other console-based strategy games from the '90s and '2000s. Necrosoft's remix on the genre begins with how it portrays the "grid"—the squares that units occupy and can move around while performing attacks.

In this Buffy-esque world, a group of college students are going up against demons invading from another (literally more three-dimensional) dimension. Like any number of video game heroes before them, they do battle by trading blows across a rectangular grid. Necrosoft's twist on the genre has two major foundations: first, characters don't directly target other objects to use abilities on, they select areas on the grid—everything is kind of an area-of-effect or line-based attack that hits the first thing in its path.

Second, Demonschool's grid is denser and more checkerboard-like than other games. That means there are more granular positions to move characters to, and the studio has more flexibility to make big, splashy effects feel meaty.

To lean into the "plan a strategy, then execute it" vibes that strategy games often lean into but don't always fully embrace, Necrosoft also lets players experiment with and then reset their unit turn order to find the best strategy each turn. Plenty of games have units move all their players at once, but often times, once a unit has moved, their action can't be reset (Into the Breach makes great use of a limited temporal reset power, but it's still a limited resource).

Sheffield said the combined point of this system is "to try to get everyone involved, use all the characters as you can," he said. Some series like XCOM or Fire Emblem task players with creating individually powerful units that can sometimes build specific synergies, but Demonschool's heroes will maximize their power when chaining combos off of each other.

He also demonstrated one final key difference between Demonschool and other tactics games. In plenty of turn-based strategy games, boss encounters often pit the player against one beefed-up enemy unit (or group of units). Demonschool borrows more from a Legend of Zelda type of boss, where players are trying to expose a certain weakness using new abilities they've learned rather than simply taking a unit to zero health.

The game also does another twist—along with needing to kill huge otherworldly demons, there's often a "side objective" that needs to be wrangled. In a fight against the 12-foot-tall skeleton that I am obsessed with, a series of smaller skeleton-type demons tried to break past Brandon's magical teenagers and reach a specific point on the grid. If too many of them reached that spot, it would be game over.

Most of the game's boss encounters will have "gimmicks" like this that differ from general combat—Sheffield alluded to one boss chomping down a harbor dock that players have to run from, and another that would turn the rectangle-based grid into a circle-based one.

"We start with a mechanical idea before the boss' [narrative] scenario," he explained, saying that he and his Necrosoft colleagues are looking for ways to "throw a wrench" in the games' traditional design logic. Each of these creatures will cap off a chapter in the game's major story, and Sheffield noted that exploring these different design ideas took priority over anchoring something to the in-progress narrative.

There's an interesting push-and-pull in making a story-based RPG there. Sheffield noted that his personal preference is to make games with A-stories that are "simple but interesting," so that he can "hang a bunch of side quests on it." Building bosses out in this way reinforced that "monster of the week" television-inspired vibe.

The question of Sheffield's tastes—and those of his colleagues—was an important one when discussing Demonschool with him. Necrosoft's twists on classic game genres like Hyper Gunsport and Gunhouse are filled with energy and made from such a unique perspective—is there anything in his team's process that could help other developers make standout games?

How to make the most of your tastes

Questions of taste, influence, and creativity in game design have to walk a fine line. It can be shallow and unhelpful to ask developers "where do your ideas come from?" when the reality is that any game is a thousand interesting ideas that get ruthlessly chopped up, iterated on, and morphed until the final thing that ships is something that no one maybe had any "idea" about.

It's also tough business to lambast a developer for not being "creative" enough. In a medium like this, sometimes it takes all of a team's effort to get a functional and fluid combat system working, and the time and space needed to put an interesting style and flow on top of that doesn't exist.

Sheffield's spent plenty of time thinking how developers of any background can develop "good taste." He gave a microtalk on the subject back at GDC 2017, and he's added to his thinking since then. To Sheffield, taste isn't just about exposing yourself to a healthy array of influences, it's also about channeling those tastes in conversations with your colleagues.

Brandon's advice from 2017 still holds up.

One of Sheffield's close friends is (fellow Game Developer Dot Com veteran) Matthew Kumar, currently writing and designing over at Future Club. Sheffield said he and Kumar often stay up late watching a lot of the same movies—often niche Hong Kong gangster films from 1992—but the two pals often have "opposite impressions" of them. "It's really interesting to talk with him about that kind of stuff because it helps both of us define what it is about our particular taste that is unique," he said.

Sheffield says that talking through those differences with his teammates on Demonschool is what's helped define the games' sprite-influenced, fashion-first aesthetic. It's not a process of averaging out their different tastes, but it's about identifying what everyone on the team feels very strongly about.

In the case of the game's art, it's Brent Porter and Catherine Menabde who Sheffield is often debating with. Sheffield seemed really proud of how this process worked out with Menabde, because even though she's one of the team's character designers, she "was not feeling confident" about fashion or good wardrobe style.

"She's a hoodie-type person in terms of personal fashion...not particularly interested in interesting color and fabric combinations and things like that," Sheffield reflected. "I found over time, I found there were certain kinds of details I could ask for that...would come out way cooler that I was anticipating?"

He pointed out one of the school administrators' character design—a stuffy, aristocratic type—and explained how Menabde designed his look. Sheffield gave Menabde some details on the character's family history, and that proved to be better direction than any details on costume direction or visual references.

The family history here was that the character's family is from the country of Georgia—so she dove into the world of Georgian culture to make something that would stand out.

"She put in these details for clothing that I had never seen or really looked at before, which winds up giving you the feeling that this [character] comes from different stock somehow and it's really neat," Sheffield reflected. "It's fun to be able to learn something new about the people you're working with while also making the game look more like it has had a bunch of specific choices made."

How to disagree productively (on dimensions)

Giving good direction is obviously important in creative work, but so is learning to disagree with the people whose tastes vary from yours. Sheffield discussed how he and Porter—Demonschool's other main artist—argue of what makes for good 3D effects. "He loves the Nintendo 64...he's ready for low-poly smear textures to come back," he said, some of his own personal ambivalence dripping off his words. "We're always butting heads on like—'what is 3D? why does this [feel like] 3D to you?'"

"We wind up having these conversations where we figure out what he likes, what I like, and what we both like, and why we feel the way we feel and then talking through those things, we're able to come up with a solution that pleases both of us to some extent without trying to just average it out or give up."

That led us to chatting a bit about how Necrosoft built a process for 3D imagery based on that disagreement. As mentioned up top, Demonschool uses 3D imagery for a specific effect: Demons and all things affiliated with them are rendered with three-dimensional graphics, and the human world is rendered with a sprite-based two-dimensional aesthetic.

The contrast is most visible in the fight with the giant skeleton—a sight so hypnotic I had to pressure Sheffield about how they landed on it.

He said the skeleton's origins began in the Japanese ukiyo-e painting Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, and that the team was looking for a boss that could be "so big it surrounds the play grid...like it's almost ready to take a bite out of it like a sandwich."

Sheffield explained that when rendering the skeleton, Necrosoft's artists riffed on practical horror effects from low-budget films and the 3D aesthetic of the Sega Saturn. The overlap between those two inspirations is such that when an unknowing viewer looks at them, they tend to ask "how did they do that? This isn't supposed to be possible to do."

In a horror movie, it's when you see a monster rip open a person's guts or body in a way that should kill the actor, but they're still there, screaming, and (mostly) unharmed. On the Sega Saturn, transparent 3D effects weren't supposed to be possible on the platform, but plenty of developers implemented them anyway.

He expressed admiration for creatives who are able to create visual effects in movies and games that don't pull the audience out of the story, but do make them ask "how the heck did they do that?" In Demonschool, he said that Porter cooked up particle effects that are physically modeled in 3D with a texture put on top of them "so that they feel present in the world."

It's a really fun visual style that sells the narrative energy of the game—demons pushing in from one world into our world—and an interesting result of combining different artistic tastes.

Often in the world of game development, designers trying to push their creativity look for more influences, more ideas they can yank from the outside world. But Necrosoft's success in building a great look for Demonschool also tells us that better communication can foster cooler creativity. It'll be fascinating to see what else the team has cooked up when the game lands in 2023.

Update: A previous version of this story referred to the games' main characters as high schoolers. They are in fact in college.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)