Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Atari VCS: Riddle of the Sphinx

Excerpt from 21 Unexpected Games to Love for the Atari VCS. Riddle of the Sphinx shows developers for the Atari reaching for complexity of design and theme, a far cry from the Pong and Tank clones the system was made for.

[This is an excerpt from '21 Unexpected Games to Love For The Atari VCS', available in the current game eBook Storybundle, which covers a number of classic VCS games that, untethered from nostalgia, may still be of interest to a player who didn't grow up with the system. Riddle of the Sphinx is the product of a developer straining against the system's extraordinary, almost ridiculous limitations, towards complexity of design and theme.]

Riddle of the Sphinx

1 player, 2 joysticks. 4K in size.

Created by Bob Smith. Published by Imagic in 1982.

Accessibility: 2/5

In a sentence: The Prince of Egypt embarks on an epic journey across the desert, facing thieves, scorpions, thirst and the wrath of Anubis, to appease mighty Ra and save the land, using only the items he finds along the way.

Riddle of the Sphinx is one of the most underrated VCS games I think. You can tell by the introduction text in the manual that this is something more substantive than Star Ship or Street Racer:

Riddle of the Sphinx is one of the most underrated VCS games I think. You can tell by the introduction text in the manual that this is something more substantive than Star Ship or Street Racer:

Hieroglyphics on an ancient obelisk tell a strange tale:

These are dark times. Death's long shadow rests across the Valley of the Kings. Anubis, jackal-headed god of the dead, has cast his curse over all of Pharaoh's kingdom. A plague of scorpions and hordes of thieves lie thick upon the land. O hear the thin whine of despair!

Sing of Pharaoh's Son, all hail the Prince of Egypt! Deliver us from this curse! Brave the dangers of the desert. Seek the answer to the Riddle of the Sphinx. Pay Anubis' ransom with your treasures, O cunning Prince of Wiles. Reach the Temple of Ra, source of light and life.

Pharaoh's heir--be wise, be wily--and beware!

It continues from there. I admire the author for their dedication to the flavor of the game. I will endeavor to translate how to play and enjoy the game from their text.

So, Egypt is represented as a long, vertically-scrolling field. You, as the Prince, are near the bottom of the screen, and can walk in all directions. Vertical movement is represented by the screen scrolling. You usually go up, but cango down, which you will have to do if you encounter an impassible barrier.

The Prince has two attributes, wounds and thirst. You can check on their values by flipping the "B&W/Color" switch on the console, one of those cases where a programmer had to make use of the limited means of interaction available on the platform. Having a lot of either quantity is bad. Both slow you down, and getting nine wounds kills the Prince and ends the game.

The Prince has two attributes, wounds and thirst. You can check on their values by flipping the "B&W/Color" switch on the console, one of those cases where a programmer had to make use of the limited means of interaction available on the platform. Having a lot of either quantity is bad. Both slow you down, and getting nine wounds kills the Prince and ends the game.

Unusually for this sort of game, the Prince heals naturally over time, losing wounds. Thirst, while never directly fatal here in pixel Egypt, can eventually slow him down to the point of unplayability, making him an easy target for pixel Egypt's many dangers. You can remedy it by visiting one of the various Oases in the game. You interact with an Oasis the same way you do with everything else in the game: stand directly beneath it, and then move up. The game's graphics engine doesn't display anything other than the Prince on his line of the screen, so if you don't do it this way it can be hard to know when you're interacting with something.

The Prince faces many obstacles on his journey. Directly, you have to avoid the thieves and scorpions that infest the desert. (You can tell the thieves because of their sexy black shorts.) Contact with either gives the Prince wounds. The thieves also throw rocks at you, and steal some of your precious possessions if they touch you. You can throw rocks at either to kill them, but your ability to do so diminishes with both wounds and thirst. So it's one of those games where, if you're in a bad state you're likely to get much worse, and must be careful to keep both wounds and thirst as low as feasible. The Prince is bound to encounter some harm, so minimizing it is of a high priority.

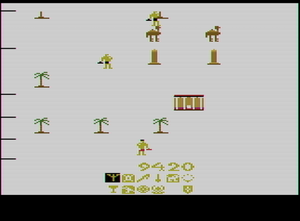

The Prince also encounters some other characters out amidst the sands. Traders, who wear red shorts (not as sexy), may either aid or swindle the Prince, depending on how many items he has. The fewer possessions carried, the more likely he'll get some goodie, while having a lot of things increases the chances he'll lose something. The Prince starts with a single item and can pick up lots of stuff on his journey, so dealing with traders is something you want to do frequently at the start and rarely near the end. There are also personifications of the gods Isis (easily recognizable by her blue clothing) and jackal-headed Anubis. Isis will often (but not always) heal and refresh the Prince, and give him a treasure if he's already healthy. Anubis will hit the Prince for three wounds! Bad dog! Throwing rocks at either will disperse their visages, but also cost the Prince what the manual calls "inner strength points," which is to say, your score.

The game's three variations affect another kind of obstacle in your way, which are invisible, supernatural walls around some of the temples and sites around pixel Egypt's landscape. There are temples to Isis, Anubis and Ra, three Pyramids and, of course, the Sphinx itself. Each wants a specific item from you, which will reward you with another item. Which item they want is the same in every game (except in the Sphinx's case), and hinted at in the manual in the form of cryptic clues from the "Royal Astrologer."

The game's three variations affect another kind of obstacle in your way, which are invisible, supernatural walls around some of the temples and sites around pixel Egypt's landscape. There are temples to Isis, Anubis and Ra, three Pyramids and, of course, the Sphinx itself. Each wants a specific item from you, which will reward you with another item. Which item they want is the same in every game (except in the Sphinx's case), and hinted at in the manual in the form of cryptic clues from the "Royal Astrologer."

In Game One, the Prince can just walk by them, but if he gives up just the right item at each he'll get something else useful in return. (If he gives the wrong item, he gets what the ancients called "bupkis.") On Game Two, he'll get stopped by the Sphinx, who must be satisfied with some obscure object you must look for. This subquest ultimately demands that you interact with the three Pyramids found earlier on your journey. In Game Three, in addition to the offering-for-treasure thing, each temple also has its own invisible wall, and you have to give up a different item at each just to move on. What is it with all these pesky gods, can't they just leave the Pharaoh’s son alone to save the land? As is written, "We have to move on! No cuttin' corners, we're on the border now!"*

(* From Translations From the Cryptical Scrolls of the Um-Jammer Lammy, #5.)

The items you find are divided, by the manual, into rough categories, although the game doesn't really distinguish between them. There's the mere "items," and then there's "treasures," and "artifacts." Each thing, item or treasure, has a specific function, although some are only as offerings at some location. Riddle of the Sphinx is interesting for, like Raiders of the Lost Ark, implementing a full inventory system, again managed using a joystick in the "Player Two" port, so remember that you'll need a second stick to play, or in emulation, be sure to configure some solution to account for the extra functions.

Mapping the P2 controller to an unused analog stick is a good solution. On the P2 stick, left and right change the item in hand. Only the currently held item (highlighted by a black cursor) has any effect on the game world, but sometimes an item must also be used to get its benefits, done by pressing the P2 button. Among the "items," there's the leaf, which heals all your wounds one time, the jug, that cures any thirst you have once, the shield, which while carried protects you from a few hits from rocks, and the staff, which seems to do nothing at all (and is hard to find; you'll have to be sneaky, in a Super Mario Bros. kind of way, to find it, hint hint).

There are treasures that duplicate all these effects, but don't run out, which is probably why they're better than plain old items. Figuring out the functions of all the objects is part of the fun of the game, so I won't spoil any more. Look to the manual for hints, and I link to a FAQ later that tells you what everything does, if you don't get any thrill out of figuring things out for yourself.

On Action-Adventure Games

On Action-Adventure Games

We've seen one foundational model of the action-adventure so far, the ground-breaking Adventure. We now have another. It's useful to see how they are different.

Adventure is a game largely about what you have and where you put it. Your intrepid dot doesn't have any statistics, which are usually considered to be part of what it means to be a role-playing game of the D&D stripe.

If your dot gets eaten, he's been ate. There's no "death by degrees" record of hit points lost. Dragon attacks are pass/fail. If you get bit by one, you know it. In Riddle of the Sphinx, it still takes three whole touches by the God of Death before the Prince kicks his royal bucket.

The difference here is a narrative one. You might consider an adventure game (whether of the action variety or not) to be a story in which the player has a role. Adventure's story is of an intrepid dot seeking a chalice. It's an epic quest, in its way, but we don't get to know much about the dot through the playing of the game. Character is proven through overcoming setbacks. About the only real setbacks the dot can suffer is getting eaten, and even then, a flip of a switch eliminates that problem.

RotS' story is of the Prince of Egypt trying to prove his worth. Nothing can kill him outright, but he can be hurt. When wounded or thirsty, the Prince cannot move as fast or throw rocks as far. His story, that is to say, has a shape. In one game he might blaze through the quest easily, finding the items he needs in the most fortuitous circumstance; that Prince is lucky, or maybe not really well-tested by his trials.

In another game, he might get hurt a lot or suffer lots of thirst, but timely finding of oases or use of items saves him. That Prince is hard-working, or clever. Another Prince might fail his quest; he was not enough for the trials he faced, but maybe that wasn't his fault? Which of these things this Prince is are determined by the events of the game. The randomness is what makes each Prince distinct. The shape of the story gets us invested in the Prince's journey. And ultimately the Prince's success of failure is the player's, experienced vicariously. A far cry from Pong, if you ask me.

Links

AtariAge - Manual -- Particularly interesting; the person who wrote the instructions really got into the theme. The whole manual is written in character. This is also where the riddles are written.

Also of interest is this FAQ by KRoper on GameFAQs, which explains what all the items do, plus the solutions to the riddles (which aren't hugely difficult anyway, just artificial difficulty).

Also try...

You gotta try Dragonstomper, covered later in this book!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like