Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In today's exclusive Gamasutra feature, a number of notable industry figures -- including Tim Schafer, Peter Molyneux, Ian Bogost, and Denis Dyack -- weigh in on the age-old question, "Are games art?"

That was Tim Schafer’s reaction when I recently asked him the question, “Are video games an art form?”

No doubt, it’s a topic that has been bandied about many times before. But with games like Okami, Katamari Damacy, Electroplankton—not to mention more mainstream releases like Metal Gear Solid—being hailed by critics (if not always consumers) these days, it’s hard not to bring it up once again.

Schafer, founder of Double Fine Productions (www.doublefine.com), the San Francisco-based development studio responsible for 2005’s award-winning Psychonauts (an artistic game in its own right), seems to agree, despite his initial reservations.

“I think it’s a worthwhile question to consider, just because it’s about the future of games,” he says.

Sighs likewise abounded when other influential developers were confronted with the same question; though, like Schafer, all eventually admitted its continued importance, especially when considering the industry’s relentless growth.

Nintendo's Electroplankton

For instance, Ian Bogost, Ph.D., founding partner of Atlanta-based Persuasive Games says, “It’s an extremely simplistic question, but the spirit of it is worthwhile. In essence, we’re asking, ‘What are video games capable of as a medium?’ And that’s a very good question to ask.”

Denis Dyack, president of Silicon Knights (makers of Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain and Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem, among others), agrees. “It’s a very important question to ask, especially to game developers, as it helps give metrics to where the mindset of the industry is.

“Even asking such a question is an indication that our industry is maturing and games are becoming a dominant form of entertainment,” he adds. “The most popular forms of entertainment—TV, music, poetry, books—went through the same perception evolution.”

Peter Molyneux, no stranger to avant garde games (it’s certainly an apt description of some of his creations, like Populous and Black & White), acknowledges the importance of pondering the artistic status of the gaming industry’s products.

“I’ve no doubt games tick all sorts of arts ‘boxes’ and affect culture as fully as any other art forms,” he says—for him the question developers should be asked is, “What are the consequences of games being art?”

Lionhead Studios' Black & White 2

That, however, is a question to be tackled at another time and in another article. Instead, the question of the day is “are games an art form?”

Unsurprisingly, the answer among game developers is a resounding “yes.”

In Schafer’s opinion, “Art is about creatively expressing thoughts or emotions that are hard or impossible to communicate through literal, verbal means.

“Can you use games to do that? Of course you can,” he asserts.

“Can you use games to do that? Of course you can,” he asserts.

Advergame designer Santiago Siri—he also maintains the aptly titled website GamesAreArt.com—holds even higher regard for gaming’s status as an art form.

“Games are not just art,” he says. “They are the most revolutionary form of art mankind has ever known about.”

The feeling is mutual for Dyack. “I feel video games are probably the most advanced form of art thus far in human history,” he suggests. “Not only do video games encompass many of the traditional forms of art (text, sound, video, imagery), but they also uniquely tie these art forms together with interactivity.

"This allows the art form of video games to create something unique, beyond all other forms of media. Simply expressed, you can put a movie in a video game but you cannot put a video game in a movie. Video games are the ultimate form of art as we know it.”

Not everyone is ready to place a copy of Super Mario Bros. alongside the Mona Lisa, of course.

Well, maybe just this once.

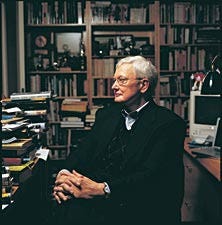

Film critic Roger Ebert is one such skeptic. On his website in 2005, Ebert dismissed the idea of video games as art by saying they “simply can’t compare to great dramatists, poets, filmmakers, novelists and composers.

“There’s a structural reason for that,” he added. “Video games by their nature require player choices, which is the opposite of the strategy of serious film and literature, which requires authorial control.”

Those are fightin’ words for game developers—especially since they came from someone partially responsible for bringing “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” to the big screen (a movie that could hardly be considered “high art”).

“I'm not going to try to guess what goes through Roger Ebert's head, but there is certainly a media literacy problem at work here,” says Bogost, who, along with fellow developer Gonzalo Frasca, edits and maintains WaterCoolerGames.org (a “forum for the uses of video games in advertising, politics, education and other everyday activities outside the sphere of entertainment”).

Roger Ebert does not think games

are art.

“Some of us grew up with videogames; others didn't. Just like every other medium, the previous generation has trouble grasping its legitimacy as an expressive form. This happened with the novel, with rock & roll, with comics. Over time, this will change.”

Adds Schafer: “Ebert says that games can never be art because they’re interactive. Huh? So when you’re watching a play, and it’s one of those plays where they interact with the audience, does it stop being art at that moment? Is that one, particular play not art, but the rest are?

“Games are art,” he adds. “If Marcel Duchamp can stick a urinal in a gallery and say it’s art, then I’m going to go out on a limb and say Okami is too.”

Gamasutra Pop Quiz: Which of the above is art?

Of course, the same questions posed by Schafer often are leveled at the video game industry. It’s easy to see the artistic value in and intention behind Electroplankton, for instance, but what about Happy Feet—or any other mediocre, mass-market game for that matter?

In Dyack’s opinion, games seemingly without artistic merit shouldn’t negate the medium’s overall value as an art form.

“Some are simply more commercial in nature” than others, he says. “Similar things exist in the movie industry,” such as the discrepancy between a mainstream movie like “Harry Potter” and an indie flick sent to the Sundance Film Festival.

Bogost sees a similar artistic connection between games and film.

Art?

“Some people distinguish the goals of artistic crafts to help understand this problem,” he says. “Film can be used for deeply charged emotional expression, or it can be used to show you how to use the oxygen mask in case of cabin depressurization. If video games are indeed a medium, then they too will speak on different registers.

“If you look at the world of ‘serious games,’ a lot of those titles are much closer to the airline safety video than to ‘Citizen Kane,’” Bogost adds. “And like film or TV or painting, there will be different modes of video game craft. There will be pop-art games and self-referential postmodern games and exploitative games and games made solely to cash in on intellectual property like Sponge Bob.”

When considering whether games deserve to be labeled as “art,” Siri says it’s important to realize the industry is still in its infancy.

The industry has only been around for 30 years, he reminds. “It’s quite probable that we’re facing a period of technological maturity that’s quite similar to what happened to the film industry from the 1900s to the 1940s, where they went from one-minute, black-and-white silent movies to full length with color and sound movies.

Siri sees the games industry moving along a similar path to maturity. “So we might as well see the first ‘Citizen Kane’ of games quite soon,” he says.

Soon, Charlie. Soon.

So the consensus—at least among developers—is that the best video games stack up quite well against other entertainment mediums generally considered “art.” Is that because game designers and developers constantly are thinking about the artistic ramifications of their masterpieces-in-the-making?

Sometimes, although as is often the case it depends on whom you ask.

“Every day we think about this,” Dyack says of himself and the staff of his Ontario-based studio (www.siliconknights.com). That’s evident in the universal theory of creating games the developer has been championing for some time—called “Engagement Theory.”

According to the theory, engagement is the product of story, game play, technology, audio and artwork.

“It’s ironic that I have expressed this in a formula, since there really is no formula for creating games,” Dyack explains. “But, we do use this theory as a guiding principle for every game we create. Essentially, we believe that the five elements of story, game play, technology, audio and artwork should always be considered when creating a game.

"We believe if these elements are balanced well you will get something that is greater than the sum of its parts and will be an engaging and immersive form of entertainment. If there is one thing Silicon Knights strives for in every game, it is to create an engaging experience. The ‘Engagement Theory’ is our roadmap toward this goal.”

"We believe if these elements are balanced well you will get something that is greater than the sum of its parts and will be an engaging and immersive form of entertainment. If there is one thing Silicon Knights strives for in every game, it is to create an engaging experience. The ‘Engagement Theory’ is our roadmap toward this goal.”

Adds Siri: “I wouldn’t be happy with myself if I didn’t practice what I preach,” who has been working for the past year on a “drama game” called Utopia, “a political game that explores the narrative possibilities of interactivity.”

“Of course, for a living, I also do commercial work at Three Melons (www.threemelons.com), where we make games for Sony, Coke, AT&T and some other big brands,” he adds. “In those projects, I get as subliminal as I can to let the final user know that games are art, although I do understand the final purpose of those projects is not always art intended.”

Learn more about Utopia at http://evoluxion.com/utopia/

Schafer’s intentions when developing a game are a bit less focused on “making art.” “I only strive to make the best game I can, and I naturally build them around things that interest me,” he says. “I like characters, and characters are best when they express feelings. But I never set out thinking, ‘Okay, gotta make some art here.’”

Molyneux says he and his crew at Lionhead Studios (now part of Microsoft) take a similar approach to creating games. “Does a painter decide to make art or paint a picture? Does a composer decide to compose a piece of music or make art? Does a film maker want to make a film or art? I think they're more concerned with evoking emotions and creating something meaningful and enduring.

“I set out, especially today, to instill emotions in the people who interact with my games, which are broader and more visual than they have been before,” he explains. “I want players to feel a range of emotions, not just excitement—that is my ambition. If on this basis some critics describe this as artistic, then I will feel like I have succeeded.”

Lionhead Studios' upcoming Fable 2

It’s obvious not all developers think about creating art as they make games, but should they?

Dyack certainly sees the benefit in it. “Thinking about games as ‘art’ is most useful because it helps guide your development process,” he says. “Unfortunately, our industry is still full of people who think of themselves as ‘rock stars,’ and that doesn’t promote discipline during the development cycle.

“We need to try to understand and analyze methods of our art form to elevate the medium and make better entertainment,” Dyack adds. “Thinking about games as ‘art’ is simply the first basic step.”

Schafer says more important than setting out to create “art” is for developers to “make the kinds of games they want to make, the games they are passionate about. That’s what is going to lead to the best games overall.”

That would be easy in a perfect world, where developers are given free reign to go wherever their imagination takes them, but that’s not always possible in the games industry, suggests Bogost.

“My guess is that the forces of commerce are putting much more pressure on developers than the forces of art,” he says. “Sell millions of copies, ship in time for the theatrical release, work 80 hours to get it done. It seems to me that these pressures are precisely the ones preventing developers from thinking about how they might use their chosen medium for other goals, beyond the ones laid out for them by the IP owner, the publisher, the producer, even their own prejudices built up in years of playing games.”

Developers lucky enough to be free of those pressures, however, should still be free to create the games they choose—whether they’re artistic in nature or not.

“If you care about injecting subtext and meaning into your game, then you definitely should,” Schafer says. “But if that doesn’t interest you then you should spend your time on the part of the game that does, and that’s great too. Games don’t all have to be the same thing to all people. They can—and should—be completely different depending on who’s making them. That’s one of the things that makes them art.”

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like