Appreciating the magic (and power) of hidden game mechanics

At GDC 2018 game designer Jennifer Scheurle breaks down how some of the biggest games "trick" players, showcasing how being a good game maker sometimes requires taking advantage of human perception.

Last summer game designer Jennifer Scheurle took to Twitter to ask a simple question: what are some great hidden game mechanics that are aimed at giving players a specific feeling?

The responses were good enough -- and numerous enough -- that Scheurle took the stage at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco today to give a whole talk on the magic of hidden game design tricks. It was an interesting elaboration on her Twitter post, so devs hungry for more examples should check out that thread.

Scheurle pointed out that responses to the question were strong, but mixed -- lots of people (especially players) were a bit shocked after getting a peek into how some of their favorite games work, and many more (especially developers) were excited to share their favorite game design “magic tricks.”

"I think in general, as a designer, we always need to be ready to explain our work to our audiences," she said, in response to a question from the audience about whether it's a good idea to be publicly sharing these kinds of hidden tricks. "I think it's very valuable, even if it causes conflict."

For example, the “rubberbanding” that happens in games like Mario Kart can be frustrating if players feel their opponents are getting an unfair advantage, but Scheurle argues it also leads to more dramatic, interesting play by pulling racers together into packs.

And in platformers like Rayman, Scheurle says that designers include a bit of “Coyote Time” (think: Wile E. Coyote running off a cliff and hovering in the air for a second) that gives players some wiggle room at the edge of platforms. This may seem unfair, but she points out that it also cuts down on frustration and encourages players to stay in a “flow” state as they’re running and jumping through each level.

Fairness for flawed humans

One of Scheurle’s core arguments is that games must be designed to “feel” good -- and sometimes that’s best accomplished by secretly stacking the odds in their favor. In BioShock, for example, the AI-driven enemy Splicers famously always miss with their first shot, giving players time to clock them and react.

“As many of you know, building super-powerful AI is pretty easy,” Scheurle said. “Building AI that ‘feels good’ is pretty difficult.”

And in Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, Scheurle says the devs sought to reinforce the game’s core themes of struggle and sacrifice by making it so that the enemy targeted by the player is permitted to break out of its animation cycle when fighting the player, making combat feel more desperate and dynamic.

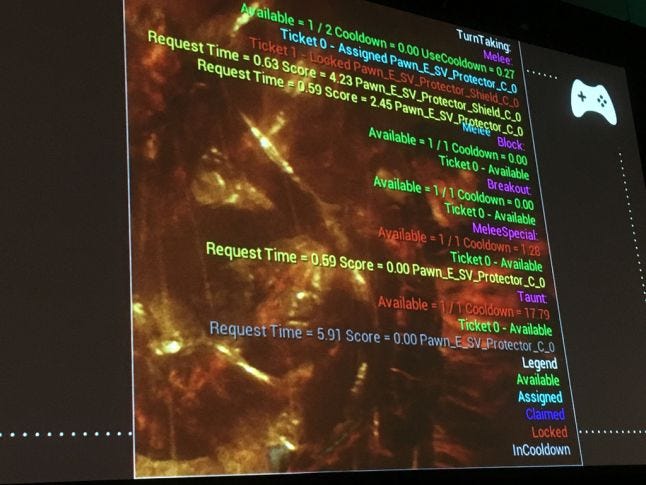

Screenshot of the Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice AI manager code, provided by the dev team to Jennifer Scheurle

Enemies behind the player are also on a timer system to keep them from attacking from behind too quickly, and enemies are managed by a ticket system which tells them which attacks to use when.

Creating and reinforcing tension

“One of the most difficult areas of keeping control over tension in your game is combat,” says Scheurle. “Mainly because it has to cater to many different players of different skill levels.”

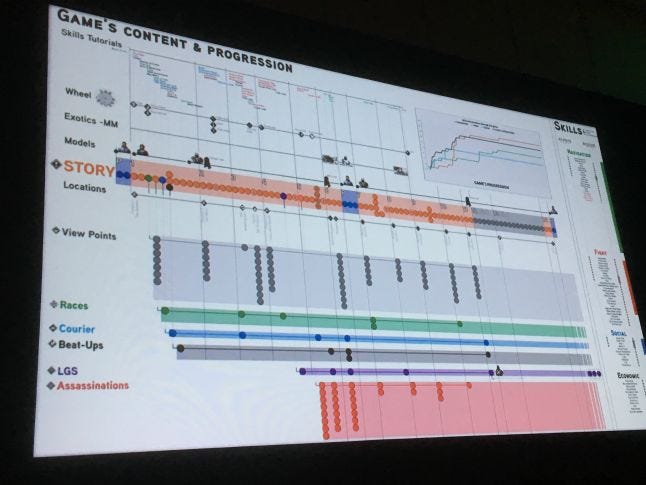

With that, Scheurle threw up a slide with a graphical breakdown of a (Ubisoft) game’s content and progression and talked about the original Assassin’s Creed.

A (poorly photoraphed) graphical breakdown of progression in a Ubisoft game, tuned to keep players engaged

According to game director Ashraf Ismail, the time it takes a player’s final block of health to regenerate in combat is actually faster than any other block in their health bar. That’s to, in Scheurle’s words, “make players feel ilke they’re escaping combat by the skin of their teeth.”

Also, as with BioShock, Assassin’s Creed has a “safety belt mechanic”: the first shot fired by an enemy will always miss the player, giving time to react.

And Scheurle adds that, according to writer Paul Hellquist, the BioShock dev team devised a special system that would dynamically remove resources from the world if players were already flush with them, and would cause resources the player were short on to drop more often. This was hooked into the difficulty settings (so things felt more scarce at harder difficulty levels) and the money/vending machine system, so the system would often give players money drops instead of the resources they needed -- pushing them to engage with the vending machines.

Setting up and controlling flow

And to control the tone and flow of a scripted game like Uncharted, Scheurle says the dev team used lots of little tricks to make sure players of all skill levels feel equally enmeshed in the story.

“It’s a core design philosophy at Naughty Dog that they always give the player the benefit of the doubt,” said Scheurle.

She went on to share some recorded footage of Uncharted 4 (provided by game director Kurt Margenau) which showcases the game’s automated system for tracking how quickly a player is moving through a section of the game (dramatically leaping from cliff to cliff while rocks are falling all around, for example), then using that data to predict when the player will arrive at a future cutscene and dynamically adjusting the speed of the game (background animation, etc) to ensure that the player’s game state can seamlessly match up with the cutscene.

“My favorite thing was the most outrageous example,” said Scheurle, closing out her talk with a specific example which illustrates how powerful a tool human perception can be when you’re designing a game.

See, in Bullfrog’s 1995 sci-fi racing game Hi Octane, game designer Alex Trowers says that all of the game’s different vehicles (the big truck, the speedy hover-car, the WipeOut-esque land jet) actually handle exactly the same.

“The different shape and the look of the vehicles was enough, in combination with the stats display, that players would never doubt the system,” said Scheurle. “It’s quite remarkable, and teaches you a lot about how game design works.”

Read more about:

event gdcAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)