Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Chris Pruett's encyclopedic knowledge of horror games fueled the creation of Dead Secret. But, surprisingly, he said that bad horror games taught him a lot more than the masterpieces.

Chris Pruett, director of Dead Secret, has made a hobby of studying horror game design for over a decade, playing almost every one he could get his hands on. He slowly developed a site that cataloged the games he'd played, eventually shifting focus onto the designs of the games that truly struck him.

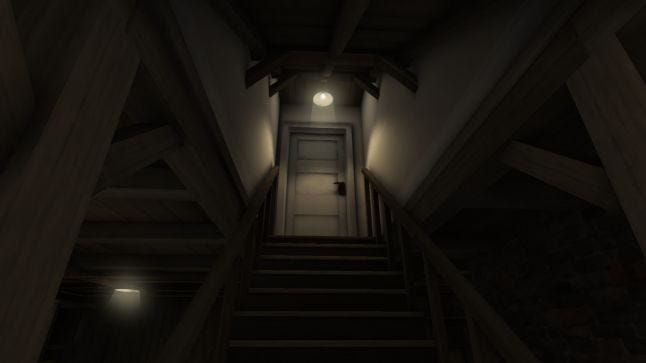

Now, he's turned this study into Dead Secret, a horror game about a journalist investigating a murder at the victim's home outside of town. Years of thoughts on design, the components of fear, and the mechanics of a good jump scare have come together in a tense virtual reality horror experience, one that, interestingly enough, came about from playing many bad horror games.

"When you play a game critically, that is, with the intent not just to enjoy the experience but also to understand how it is put together, good games can be hard to read," says Pruett. "Games are, at some level, a collection of decisions that the development team made. To play a game critically is to try to understand these decisions so that maybe, hopefully, the lesson can be applied to the development of some other game. But good games are really hard to parse into reusable units."

Good games, by their nature, flow together well. They're a collection of development ideas that gel into a pleasant, coherent gameplay experience. If this is done well, the ideas work together seamlessly, and it is often that cooperation of ideas that makes the game fun to play. If one of the ideas was not present in the game, the others would crumble.

This is true of horror. The creaky house doesn't frighten a player if the scares are poorly-timed or ineffective. The most jarring jump scare may only irritate the player if there is an improper lead-up to its appearance due to lack of tension, music, or atmosphere. If the monster isn't lethal enough, or the player can combat it easily, the player doesn't fear it. Every idea needs to work in tandem for a game to be good.

This makes it a challenge to separate specific good ideas for a horror game, as they are all integral to each other. Taking one piece out may not necessarily work outside the entire set of ideas. "For example, is Resident Evil 4 better or worse because of its decision to forbid simultaneous movement and shooting? Clearly the developer felt so strongly about that decision that they chose to buck precedent." says Pruett. "Would Resident Evil 4 be just as good with a different inventory management mechanic? A different control system? A different level design? It's hard to tell. The whole thing works so well that it's difficult to separate strands that might be repurposed from the whole."

With the various parts working so well together, it's not easy to separate what might work in other situations. They rely on each other, so it's not always easy to tell what it is that makes a good game click with an audience. "The best games transcend the sum of their parts and create something much more impactful. The trick is figuring out which, if any, of the decisions made in a good game might be applicable to another game." says Pruett.

Pruett observes that many bad games have good ideas that just did not work together. Some of the worst games at least have nuggets of interesting ideas that can be pulled from the wreckage and repurposed into another game, seeing if they work better with another set of ideas. It's very rare that an idea is so flawed that it will never work, and so many good ideas exist in games that are considered 'bad' due to the ideas working poorly together.

"Bad games often have one or two issues that scuttle the whole experience. And those are easy to see, easy to parse out, and (usually) easy to understand," says Pruett. "The lessons from failure are quite clear, while the lessons from success are difficult to isolate. I've also found that most bad horror games have a couple of good ideas that never really get off the ground, and some of those are really interesting."

As an example, he cites a hiding mechanic from the Kinect horror game Rise of Nightmares. "I thought the Kinect zombie puncher Rise of Nightmares was a pretty bad game, but it has one mechanic that I liked: holding your body still so a blind enemy won't hear you. This mechanic has more recently been used to great effect in the (much better) VR game Dreadhalls."

"It makes a lot of sense for these titles because both operate on control systems that can read your body movement," he adds. "You might play Amnesia and think that hiding without moving is a cool mechanic, but it doesn't stand out as an interesting idea the way it did in Rise of Nightmares because Amnesia does all sorts of other things right too."

With a bad game, the ideas can be better compartmentalized, especially in horror. Many bad horror games can have tense moments of alarming effectiveness. Jason's sudden, jarring appearances in the NES game Friday the 13th can still terrify the player, even if the rest of the game seems clunky and unpleasant to play. A single, fear-inducing idea can stand out more easily amongst the clutter of a bad game, letting developers more easily pull out the neat ideas within.

Dead Secret came about from many of the good ideas Pruett has in his head from years of studying horror design, but a lot of those ideas have also stemmed from bad horror games.

"In Dead Secret you acquire a mask with special lenses that allows you to see things that are not normally visible to the naked eye. The idea for this mechanic came from a pretty bad Dreamcast horror game called Carrier, which has a helmet that can look through organic matter. The idea was solid, but Carrier hardly ever uses it." says Pruett.

The mask provides an interesting idea, one that allows the developer to hide important items, and more terrifying developments, in plain sight around the player, only requiring that they don the mask to experience the results. This creates an additional bit of tension in what appears to be an empty room, and is especially effective when the player's line of sight is limited in the VR gameplay of Dead Secret. Yet this idea came out of something largely unused in another, less effective horror game.

A weak protagonist gives an additional sense of dread to the player in that they cannot effectively deal with danger. In many horror games, the player moves slowly, cannot run, or has difficulties fighting back that make a suspension of disbelief difficult. If a player is wondering why they won't run or hit back, they're spending time thinking about why the system will not allow them to act believably in that situation. They're not scared of the monster - they're considering systems.

"In Dead Secret, the protagonist has one arm in a sling. This doesn't pose too much of a problem until Woodcutter, a killer in a raincoat and Noh mask, shows up. There are a lot of great gameplay reasons to hobble the protagonist this way, but I think the original inspiration for it came from a terrible horror game called Michigan." says Pruett.

"In Michigan, you play as a cameraman filming the destruction of Chicago by some sort of evil mist. One thing about Michigan that was really interesting is that it doesn't let you interact with the environment directly Your hands are full because you're holding the camera. That means you are plausibly handicapped in a way most game protagonists are not. You can't even open a door on your own--the film crew has to do it for you. I liked this idea quite a lot, and though Dead Secret's implementation isn't so dramatic, breaking Patricia's arm opened up a lot of game design opportunities for us."

By giving the player's avatar a handicap of some sort, it becomes easier for the player to accept limitations in the game. An effective use of a broken arm, for example, has this desired effect while also increasing a sense of danger. A player has to feel that they are believably vulnerable to feel fear in a horror game. They no longer wonder why they won't fight back, and instead accept the fearful situation a little easier.

"A core idea is the concept of disempowerment. In horror games it is necessary to put the player's avatar in a situation that seems overwhelming. The severity of the situation is dictated by the design of the avatar itself. Resident Evil 4's Leon is constantly battling chainsaw men and giant trolls because he's a very capable character and big bombastic enemies are what it takes to put him in dire straits."

"Fatal Frame, on the other hand, can get away with ghosts because its protagonists are presented as normal (or even meek) people. Part of breaking Patricia's arm in Dead Secret was intended to disempower her without making her character any less capable." says Pruett.

Pruett drew out many interesting ideas from bad games, carefully considering how to make them most effective in his VR horror game. By utilizing a mask, he considered how changing the player's perception would add to the tension of an empty room, letting him place new monsters in what was, effectively, plain sight. It also lead him to consider new avenues that would make his players feel that they were in believable danger.

This stemmed from taking a look at bad games along with the good, drawing out the interesting ideas that likely excited the development teams of these games so long ago. Interesting ideas exist behind the development of many bad games, and it is that very unpleasantness that can make it easier for developers to draw out what they need or can use in their given genre.

Not only this, but some ideas in supposedly bad games might just not have been a good fit for the technology and consoles of the time. "The value of VR to horror games cannot be understated. So many games spend so much effort trying to convince you that the space your avatar occupies is real, and in VR this feeling is almost trivial to achieve." says Pruett.

An idea that wasn't all that effective can work wonderfully in VR, where the player occupies the space of the avatar, increasing believability and immersion. What was once considered ineffective and laughable can be easily drawn out and put to better use after being witnessed in a bad horror game.

A genre's past contains a rich history that can give developers many new, exciting ideas for their games, but they should not limit themselves to the best in their genre. A good idea can be buried anywhere, and in even the worst games, there is something worthwhile. It's also easier to see, too, making every gameplay experience into something useful on some level.

Some of the worst games you've ever played may contain an idea for the next great game, horror or otherwise. Do take the time to look.

This article was first published April 26, 2016. It has been updated in 2024 for formatting.

You May Also Like