Alt.Ctrl.GDC Showcase: Threadsteading

"We wanted to work on a game that would involve real time control on a quilting machine. The mechanics are inspired by the Empire Builder railroad-building games and territorial control board games."

The 2016 Game Developer's Conference will feature an exhibition called alt.ctrl.GDC dedicated to games that use alternative control schemes and interactions. Gamasutra will be talking to the developers of each of the games that have been selected for the showcase. You can find all of the interviews here.

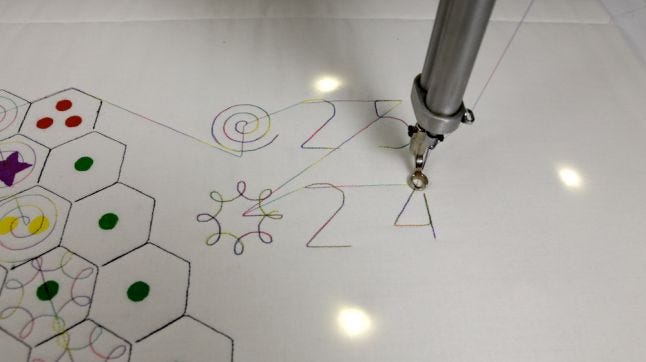

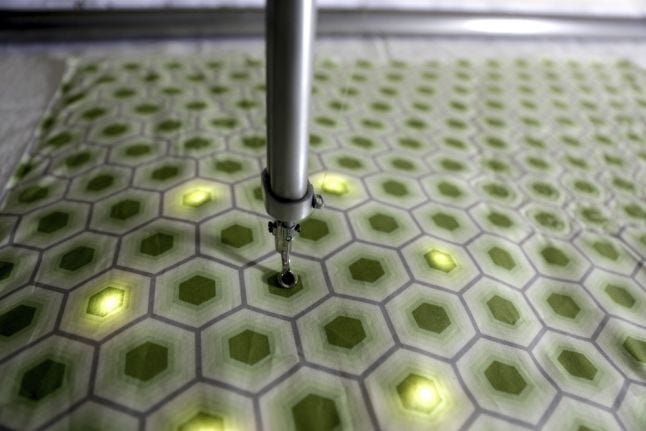

Threadsteading turns sewing into a territory-control board game. In it, players deliver commands to the quilting machine to take control of a hexagonal space, stitching a permanent mark on the fabric. In the end, the players will have created a quilt for themselves - a tangible reminder of the game they played together.

By using a hexagonal grid, keeping an unbroken thread line, and encouraging evenly distributing lines across the game space with little backtracking, developer Gillian Smith, along with team members April Grow, Chenxi Liu, Lea Albaugh, Jen Mankoff, and Jim McCann, have taken the rules of quilting and turned them into a game.

This repurposing of a large, practical machine into something fun that creates a permanent, useful, physical memory of the time spent in play is set to appear at GDC's Alt Ctrl GDC exhibit. Smith answered some questions about the game for Gamasutra.

What were each of your roles on this project?

Smith: We split into two different mini-teams during a game jam at Disney Research Pittsburgh. Jim and April spent most of their time trying to get interactive control working for the quilting machine -- decoding the language it uses and figuring out how to send commands and get responses. Gillian, Lea, and Chenxi spent their time designing and iterating on the game design and controller assembly, as well as writing a simulator for the quilting machine so we could prototype the game before we knew how to communicate with the machine. Jen gave us great feedback on the game towards the end of the week-long jam and helped work through controller design problems.

How do you describe your innovative controller to someone who’s completely unfamiliar with it?

Smith: There are two versions of our game with two different controllers: one is a thirteen foot wide long-arm quilting machine, the other a personal embroidery machine. You can think of both of them as sewing machines that are programmable and can receive instructions from a computer attached to them. The main differences are the size and that for a quilting machine, the needle moves across the fabric and for an embroidery machine, the fabric moves under the needle.

There’s a custom controller attached to the machines that’s a set of buttons that let the players decide which direction to move. On the quilting machine version of the game, the controller sits underneath the fabric so you press down on the quilt surface. On the embroidery machine version, it sits off to the side because of space constraints. We’ll be showing the embroidery version of the game at Alt.Ctrl.GDC -- the quilting machine version is just too big to transport!

What's your background in making games?

Smith: I am a game design professor at Northeastern University whose research is in procedural content generation, computational crafting, and gender issues in games. I make experimental games that incorporate innovative or unusual technologies, and have had my games at both academic and indie events. I co-organized a workshop called {Craft, Game}Play that explored the intersection of handcrafting and game design.

Lea is interested in computationally-driven games, particularly games that mediate social interaction or perception, as part of a broader place- and thing-making practice. She has exhibited at various indie/art game events including Vector (Toronto) and Different Games (NYC). She's also an enthusiastic member of the interactive fiction community and has taught workshops for a variety of audiences on creating IF.

Jen is new to game design, though she has enthusiastically played games of many types for many years, particularly board games and games of strategy. She is also a fan of beautiful materials and physical artifacts.

April started programming in order to make games, especially those stemming from feminine interests. As an undergraduate, she led a team to make Pattern, a crocheting game using the two joysticks of an Xbox controller as yarn and hook. As a graduate student, she has worked with Kate Compton on a nucleosynthesis simulation game, Stellar, and has since been designing creative and playful interfaces for traditional crafts such as embroidery, knitting, and crochet.

Jim was a full-time indie game developer and is now a hobbyist game developer by night and research scientist by day. His one-person studio TCHOW llc has released two commercial games: Rktcr, an astoundingly difficult vehicular platformer for Windows, MacOS, and Linux; and Rainbow, a [not really] highly-realistic rainbow driving simulator for iOS and Android devices. He expects to release two more games -- Chesskoban and Cubedex -- in the near future, though he has been saying that for years. He also occasionally builds games for Ludum Dare or just for fun.

Chenxi occasionally makes games and spends much more time playing them, especially visual novels and puzzle games. She participated in developing Morris, a puzzle platformer where the player takes control of Death, and enjoyed programing visual effects for that game.

What development tools did you use to build Threadsteading's software?

Smith: Threadsteading’s code is written in Python and runs on a computer that’s hidden from the player’s view.

What physical materials did you use to make it?

Smith: The original game on the quilting machine runs on an Innova 32” Long-Arm quilting machine; the embroidery machine version runs on a Singer SE-200 embroidery machine. The custom controller was laser cut from acrylic, has LEDs to illuminate the buttons for valid paths the player can take, and uses an arduino to interface to the computer. The gameboards are digitally printed on woven cotton fabric.

How much time have you spent working on the game?

Smith: The game was made in a week-long “game jam” at Disney Research Pittsburgh. Since then, we’ve been working to polish it and port it to the embroidery machine so we have a portable version of the game to show off.

How did you come up with the concept?

Smith: We all have different research and game design interests that give us combined expertise in experimental game design, computational crafting, and human-computer interaction. We knew we wanted to work on a game that would involve realtime control on the quilting machine. The game concept came from a combination of needing something simple that we could accomplish in just a week, and needing to work with the constraints the machine gave us. The mechanics are inspired by the Empire Builder railroad-building games and territorial control board games.

Why make a game that can be played on a quilting machine?

Smith: We’re all interested in programmable machines for crafts. They are typically used to automate work that would normally be painstakingly done by hand. I think part of why this project is interesting is that it looks at how we can make these machines more interactive and produce new kinds of art and interactive experiences.

Quilting is a craft that’s predominantly and historically practiced by women, and uses some pretty specialized equipment and sophisticated programmable machinery. Gaming is a lot more balanced in the gender of participants, but societally still seen as quite masculine. So some of our interest is also in juxtaposing these two differently gendered activities.

How does it feel to play a game that creates a tangible, touchable memory of itself in the real world? What is it like to use play to create something useful?

Smith: I think getting a tangible artifact adds to the permanence of the game decisions you make, and makes me pause longer to strategize. There’s no option to undo a move once you’ve hit that button, because the machine can’t un-stitch your path. Players can take home mementos, and being able to see the paths each player has followed also gives you a bit of history to look at when you finish playing and think about what different paths could have been taken.

How did the rules of quilting affect the rules of the game?

Smith: The main “rule” of quilting is that you want a single unbroken line of thread whenever possible, otherwise the thread can tangle or you will spend far too much time knotting and cutting threads on the finished product. You also don’t want to quilt over the same area too many times (to protect the fabric) and aesthetically speaking you generally aim for equally dense quilting across a surface unless you want to highlight a particular area of the quilt.

These two rules were the main constraints driving the design for Threadsteading -- player movement is constrained to follow a single unbroken line, and the rules and boards are designed to encourage player exploration across the entire space roughly equally without too much going back over existing territory. We also adopted a hexagonal grid because hexagonal grids are as common in quilt design as they are in game design.

How do you think standard interfaces and controllers will change over the next five or ten years?

Smith: There will always be a market for the standard interfaces and controllers we have now, I don’t think experimental and alternative controls are going to take away a developer’s need for standardization, or the market-driven desire to just buy a game that works on the hardware that people already have at home.

But I do think there will be more options in the next decade. People talk about the move to VR being the next big step, but I’m hoping that the rise of personal fabrication machines will also give us the ability to have games that need and produce customizable, physical objects. I’d love to see games where players decide what the controls can be (products like the MaKey MaKey let people do this already!) and give more power and customization options to encourage players to use their imagination in more parts of the game experience.

Go here to read more interviews with developers who will be showcasing their unique controllers at Alt.CTRL.GDC.

Read more about:

event-gdcAbout the Author

You May Also Like