Adapting games like Fallout and Doom to play well on a board

Fantasy Flight Games' Andrew Fischer and Jonathan Ying walk Gamasutra through their processes for adapting the worlds and systems of games like Fallout and Doom into engaging multiplayer board games.

The task Jonathan Ying found ahead of him was, as he modestly describes it, “rather daunting”.

Ying, a designer at Fantasy Flight Games, had been offered the chance to design a new iteration of the DOOM board game to go along with the newest video game release in 2016. He’d be taking a fast-paced, action-oriented, feast for the eyes and trying to turn it into a turn-based tactical miniatures game.

As he readily admits this was almost as far on the other side of the gameplay spectrum as a thing can be.

From the earliest days of Civilization’s development as a glorified version of Risk to Jake Solomon’s handcrafted cardboard version of XCOM: Enemy Unkown, prominent turn-based or grand strategy games have often started life as board game prototypes. Video game adaptations of popular board game properties are usually from within this genre as well: see Space Hulk, Axis & Allies, Zombies!!!.

Less common, and arguably far more difficult, are board game adaptations of popular video game IPs.

Video games can contain a multitude of interlocking complex systems and distilling these into a board game is a unique challenge, a challenge that Andrew Fischer, lead designer of Fantasy Flight's 2017 Fallout board game, is very familiar with. With Fallout’s status as a huge open-world video game full of player freedom and choice, he tells me that his first concern was just how he was going to adapt such a complex video game into a simple two- to thre-hour board game.

No Doomslayers allowed

To begin with, both Ying and Fischer had to contend with the fact that the properties they’d been tasked with adapting were primarily know as single-player experiences. Ying and Fischer were both aware of how adding additional players to these properties had to work mechanically and fit thematically.

"[There are] so many moving parts to these sorts of games that we’re still learning how to craft a fine-tuned machine out of them."

For Ying, implementing the co-operative mechanics into the DOOM board game was a battle against an unspeakably powerful force; The Doomslayer. The “singularly powerful superhuman warrior” that acts as the newest DOOM video game’s protagonist would have been a poor fit for a board game focusing on cooperation.

It was in the digital game's multiplayer suite that Ying found his inspiration. Here each player is acting as generic marine training for combat, none of whom have the same superpowers as The Doomslayer. This enabled Ying to more easily balance the game and allowed him to make the board game act as a prequel of sorts to the digital experience.

Fischer’s task in this area, on the other hand, was a bit more multifaceted. Fallout is known first and foremost as a meaningful single-player narrative experience, and Fischer felt that “impactful, frequent player interaction can often be diametrically opposed to that.” Fischer’s worry was that player interactions commonly found in adversarial games might lead to what he calls “denial-based play”; players deliberately preventing others from experiencing key areas of the game.

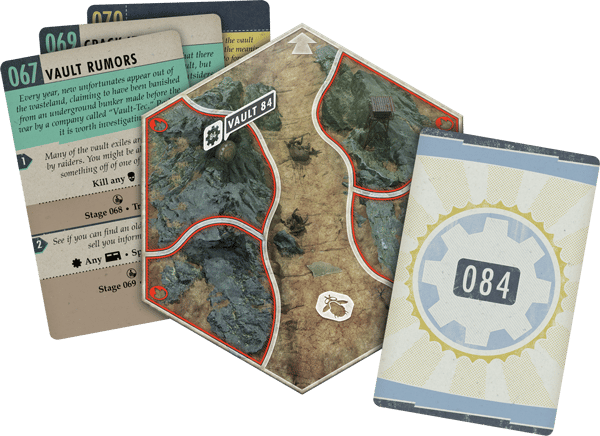

It was the process of implementing the quests into the Fallout board game that led to a breakthrough for Fischer. He tried private storylines for each player, but that led to little player interaction. Group quests with faction recruitment led to players ganging up on one another. The final version of the quest system made all quest outcomes shared between the game’s players, but Fischer was still faced with how information in board games is often available to all players.

“Certain players would band together for a common goal, or ignore objectives they were concerned they would have to compete for,” Fischer explains. To combat this, the game’s scoring system was hidden so that players were never sure of what the others were doing, leading to risk taking and negotiation that was “very appropriate to the wasteland.”

Ying and Fischer each had clear objectives in mind when designing the core mechanics of their adaptations. Ying knew that the DOOM board game “needed to really hammer home the speed of play” that was core to the 2016 digital iteration. Ying had previously worked on the Star Wars: Imperial Assault board game, another tactical miniatures based game that Ying used as a starting point for his work on DOOM.

Ying explains that Imperial Assault had a slower pace to its turns which allowed for “minutes of discussion and strategizing each round before a player even touched a miniature”. Ying was concerned that allowing this slower pace to flourish in DOOM would lead to the board game lacking the frenetic pace of the video game, and what he calls ‘clean up attacks’; players wasting actions to dispatch an enemy with one or two hit-points left.

Eliminating 'analysis paralysis' around the table

Rather than punish players, Ying wanted to reward them as the video game did for fast, expansive movement and aggressive, ever-changing tactics. The ‘Glory Kill’ mechanic, adapted directly from the video game, rewards players for pushing the attack and quickly dispatching enemies by allowing them to recover damage, and gain powerful single-use abilities.

Adapting DOOM’s dynamic tactical decisions players would bring Ying back to his work on Imperial Assault, a game in which your limited equipment would improve over time. Ying wanted the tactical options in DOOM to be more free-form so that players would be “juggling all sorts of different weapons depending on the situation”.

To ensure that players would be switching up weapons frequently and to eliminate ‘analysis paralysis’, each weapon card that players can acquire imbues their marine with a particular set of actions. Ying explains that whilst the Shotgun would give a player good movement and be good at close range, the Assault Rifle would slow the player’s movement but allow them to attack at a greater range. This was to ensure that each choice of weapon by the player felt significant and “gave each weapon in DOOM its own fine niche.”

.png/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Fischer approach in adapting the actions available to players of Fallout had to differ greatly from Ying’s. His goal was not to adapt a linear experience, rather to replicate the sense of freedom found in the Fallout video games. Fischer says that the biggest design priority was to ensure that the player never felt as if the game was holding their hand.

Fischer wanted players to be able to “explore the map, encounter any location they want and fight any enemy they want right from the beginning”. Fischer also tells me that he wanted to keep the list of actions available to players simple and easy to engage with. Keeping both of these objectives in mind led to a process of gradually cutting down the list, combining and simplifying actions when necessary, and ultimately making sure that each simple action had a multitude of applications. Fischer uses the example of the ‘encounter’ action, a single verb that allows players to explore wastelands, shop at towns, search for clues introduced by quests, talk to NPCs, and much more.

With a wasteland to explore comes monsters to fight, and it was here that Fischer wanted to incorporate a key piece of visual iconography from the Fallout video game series. The V.A.T.S. mechanic has been in the Fallout series since the first entry, and is used to target enemies’ weak points in the series’ combat. Fischer told me that in an adventure game like Fallout where so much else is going on, the combat needed to be fast and simple.

After trying systems that used cards, dice, and other tokens, he settled on a dice-based system. The dice were “quick and visceral to start throwing around” and allowed for a lot of small, important players choices (such as changing dice to other faces, or retooling certain dice). Fischer’s rationale behind integrating the aesthetic of V.A.T.S. into the dice combat system was two fold: using the color scheme of V.A.T.S. would utilize Fallout fans’ primed knowledge of what the system is for plus, Andrew admits, it just looked great.

Adapting video games to run on organic computers

A major hurdle both Ying and Fischer’s adaptations faced was the obvious lack of any sort of computing power. Physical adaptations of both of these properties would have to compensate for the fact there would be no processes going on behind the scenes, no constant micro-managing of the player’s actions, and no way for the game to organically react in real-time.

The challenge faced by Fischer in adapting these systems for the Fallout board game was similar to the difficulties in adapting the player actions; there were just so many of them. Fischer tells me that they there were a large amount of elements they wanted to adapt for the board game, and that even after taking steps to simplify them, the management of the game could be quite complex for players.

Asking players to perform this level of micro-management raises an important question; how do you make this act enjoyable? Rewarding players, Fischer says, is key to maintaining engagement with this process. He found that players are “much more likely to remember to do small maintenance actions when they are tied to their advancement and potential victory in some way.” Distributing loot from defeating enemies and levelling up their characters not only helps players get that one step closer to victory then, but also ensure that the game itself keeps ticking over smoothly.

Ying’s solution to this challenge again came from his earlier work on Imperial Assault, a game that utilizes an asymmetric 1 vs. many system. One player is tasked with controlling the entirety of the Imperial forces, whilst the other players each control a Rebel hero character. Ying explains that the previous 2011 Doom board game was the first of the studio’s games to utilize this 1 vs. many mechanic, and because of this he always intended on implementing it in one form or another.

Previous to the final product however, the system went through many different versions. There was a purely cooperative iteration that needed a complex AI system to function properly; Ying says this was “less interesting” than a human controlled opponent. ‘The Doomslayer’ cropped up again in an early prototype, this one featuring one player as the aforementioned superhuman with the other players controlling the demon forces. Ying explained that the issues with this rule set arose either from the fact that “the Doom Slayer was dominating and it felt like you couldn’t make progress with the demons,” or “he was getting stomped by four players at once and felt helpless.” Whilst both of these ideas had promise, Ying decided to focus on a set-up similar to Imperial Assault that would provide a good “pick-up-and-play game”.

So how then to encourage the Demon player to act like a Demon? Ying says that the natural assumption when designing this aspect is that the most experienced player will act as the Demon. With this however comes the risk that the Demon player will hold back in some way in order to make the game more enjoyable for the group. Ying’s solution to counteract this was to make the marine players “strong and intimidating so the Demon Player will be forced to cut loose “. He also added a deckbuilding mechanic for the Demon player that allowed them to create their own playstyle, a level of customisation that would encourage experimentation by even the most experienced players.

It’s fascinating how both Fischer and Ying differently approached the process of adapting the DOOM and Fallout properties. Such dynamic and emergent video games call for inventive methods of adaptation, but it’s an ever-changing process. Ying acknowledges that there are “so many moving parts to these sorts of games that we’re still learning how to craft a fine tuned machine out of them”. This is perhaps the clearest and most succinct summation of the unique challenges he and Fischer faced, and what other designers have to consider when other video games decide to make the leap to the table.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)