Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this extensive interview, the general manager of Zynga Beijing expands on the company's creative philosophy - rely on metrics, not on what game designers think is "cool" or creative, and always serve the users.

[In this extensive interview, the general manager of Zynga Beijing expands on the company's creative philosophy -- rely on metrics, not on what game designers think is "cool" or creative, and always serve the users.]

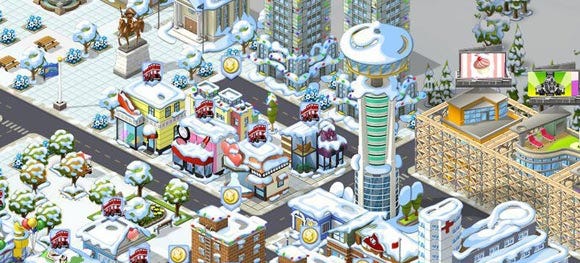

Zynga has firmly established itself in the social games space as it continues to launch hits like CityVille. But according to Andy Tian, scaling up is the company's primary concern -- delivering the right content and features to the company's audience is paramount. This was why Zynga acquired the company Tian co-founded, XPD Media.

Tian, who has a background with Google, has a philosophy of letting analytics and user feedback drive game content. He believes that games -- or social games at the very least -- are a craft, not an art.

Therefore, he believes they are best designed using feedback from the users than relying on what game developers think is "cool" or "creative".

His studio is primarily concentrated on developing games for the Western market, not Eastern -- though his firm recently launched an adapted Chinese version of FarmVille currently growing on Facebook.

Still, Tian spoke at GDC China last month about his ideas on how social games development must be undertaken, which he expands on in this extensive Gamasutra interview.

What's the primary focus of setting up in China? Is it using the expertise of Chinese game and web developers with things like microtransactions in a market that can capitalize on it? Or is it the cost savings gained from developing here?

Andy Tian: Cost saving is never a focus. It's a matter of talent. It's a matter of ability to scale. This is why we're acquiring some new companies, because we wanted to scale faster and at higher quality. I mean, we're not the only ones, right? Everyone else has that option, too.

In your GDC China presentation, you were talking about Mafia Wars and FarmVille, and you said there's no shortcut; you have to scale up your team if you want to provide the content that the increased audience expects. And I found that to be interesting, because at a certain point it's not easy to scale with high quality staff. It's not easy to recruit. Eventually you're going to reach a ceiling.

AT: Any fast-growing company faces that issue, right? Your opportunities are enormous. And in time, your resources are always very, very limited. This is what I found even at Google. You think that Google has a ton of resources, right? No, very, very limited resources to do what we actually want to do.

So, ultimately, yeah, it's all about prioritization, like where do you actually put resources where it really, really matters? That's why metrics-driven game design and ongoing game improvement is so important to use, because we can only do a portion of what we actually want to do. But where do you prioritize? Not because it's cool games, but because it actually drives the business forward.

I was really struck by your statement about games being a craft, and that metrics are a tool to hone that craft, essentially. And that is your philosophy.

AT: Yeah. I mean, our philosophy is always that we take a web approach to building. What we're actually building is web-based entertainment. So, I would say, you know, MSN Messenger and [Chinese instant messenger] QQ, these are also web-based entertainment products too, because chatting is also entertaining and also contacts people, too. We're doing the same thing, but infusing that process with fun.

A lot of people in the game industry, like they want to build games because they're gamers, right? They like games, they play a lot of games. Our audience is actually in fact not gamers. The 200 million users out there who maybe play just a very, very basic kind of game, and that's it.

So, how do you, as a gamer, build a game that can be continually enjoyed by the really, really non-gamers, like the students, like accountants, lawyers, like housewives, househusbands, children, etcetera?

When you look at making a game for Zynga, is it more about expanding to audiences that you haven't tapped before, or is it increasing the satisfaction of the audiences you've found so far?

AT: I think it's always both. Like CityVille, which recently launched. That's a new category for Zynga. And, you know, FarmVille for Japan, it's a new market and a new set of users. So, as a company, you always do both.

At the end of the day, you need to build products that -- as long as you have a very clear idea of why you're building a product, whether it's to target a new segment, a new genre, or a brand new market, then you can shape the product development toward that.

You don't want to be confused about it, a fuzzy idea. "Oh, I think this is where I want to go. Let's build it first." That always, you know, has a lot of problems.

Is your studio building games for platforms other than Facebook, or are you concentrating only on Facebook?

AT: We're focusing right now on Facebook.

So, you're not really concentrating on properties for the local market, where we're physically sitting right now?

AT: [laughs] No. Of course, we're watching this market very carefully, but I think it's still early.

You talked about how virality isn't as much a concern in China. I don't know whether you were trying to that it's not a concern in the sense that Chinese users behave differently, or it's not a concern because the platforms behave differently here.

AT: Because the platform behaves differently. Because virality is not for free. Virality, like I said, needs to be supported by good communication channels, and making them to be viral. You can't just be viral So, Facebook has done an awesome job of that. This is why they're awesome partners. Because it's about having those channels and being able to manage those effectively. I think that China's platform still has a way to go toward that.

Do you feel satisfied with Facebook even given the changes they've made to their policies for communication in recent times?

AT: Sure. Facebook is the de facto platform for the Western audience -- I think for the global audience. So, they're not in a business of making games. We are. So, obviously, there will be some differences on how they manage the platform versus how we want it to be. But as companies go, we just take that and we work with that. At the end, there are always things that we can do better and we can optimize more, and we expect Facebook to continue to evolve, too.

I'm very curious about your use of metrics in light of the discussion of bad metrics versus good metrics. Tracking the wrong thing, or tracking things, and getting the wrong interpretation of what's going on. Have you found there have been a lot of pitfalls with the way you've approached metrics?

AT: Well, I think that's always the case, right? Everything can be done the right way, can be done the wrong way. But how you track things the right way is a difficult question for sure. I think that a lot of the time, you don't necessarily know what you are doing...

I think maybe the way to avoid having bad metrics is to always tie everything at the end -- even though the problem may be very, very complex, at the end, the conclusions, the cause and effects have to be really crystalline clear to people.

If someone cannot understand what you mean after analysis, you haven't done a good enough job. Part of analysis is not to make things complicated. It's to make things simpler and easier to understand for people to make decisions. If it's not simple, if it's not easy, probably your analysis is not right. I think that's probably all I can say.

You discussed how, with Mafia Wars, the team implemented boss battles, and that didn't really increase the metrics you wanted to increase, versus adding a simple lottery system to FarmVille. You made it sound like these mechanics could be repeatable across multiple games.

Do you feel that developing social games is more about defining successful mechanisms and then targeting different audiences with the same mechanism via different ways of presentation?

AT: You should always look at best practice metrics and mechanics. You always see how they can apply. I think it's one of those things where there's no clear-cut answer. Some things can be applied across games, because people are people, right? People are people, and they have the same psychological drivers.

But some things cannot be applied to other games because game types are different. People's expectations of how a game will behave is different. For example, if I start selling guns or tanks in FarmVille, people are going to say, "What the hell is that?" [laughs] That's beyond people's expectations.

But things like daily returning rewards, that can be applied to both Mafia Wars and FarmVille. Again, it's kind of a case-by-case basis.

With every new platform that comes out, it seems that people start trying to define new ways to go with it, and then a couple approaches become successful, and things start to coalesce around that. Do you think that's happening with social games?

AT: I think that's the [current] stage of development, too. So, right now, social gaming seems to be a couple different categories, but still many, many categories and genres have not been "socialized" yet, shall we say? I think what you said, actually literally, may be right.

It was interesting that you talked about that game [Guild of Heroes] that Zynga worked on, the Diablo-ish game that ended up not really panning out. And the concept that you can't really "socialize" a single-player game experience.

AT: I don't want to say you can't really socialize... [but] It's really, really hard. I think it's really, really hard because you can definitely take a lot of mechanics, but it's really hard to take a whole single-player game, add five social mechanics, boom, voila, you have it.

I mean, that's a simplistic view that many people have. But ultimately that will not really work because people have very different expectations. Again, it's about player expectations, what they want to see with the game. Do your future expansions jive with that? And that's one of the problems which makes single-player games hard to work as social games.

FarmVille, ultimately, is a one-player experience, right? You manage your own farm. You interact with other people, but it's not fundamental to the core gameplay interactions. First of all, it's asynchronous. What separates that from a traditional game in terms of a single-player play path?

AT: Traditional console games, you don't have any interaction unless you go into multiplayer battles, during campaigns. The single-player is self-contained. But like you may not necessarily want to be at a party 24 hours a day, I think there's something cool about the pace and tempo of social gaming interactions.

Because it's asynchronous, you don't have the huge pressure you [could] have, "Oh, I must respond to this person," [instead, it's] "Okay, I can respond to them a little later." But that doesn't lessen the social obligation or social capital that you have.

I think it's precisely because it's asynchronous that people feel "I can come back to the game anytime." Because remember, for social games, unlike MMOs -- a synchronous game -- we don't expect, require, or design a game for users to play hours a day. It's like 10 minutes, 15 minutes a day.

I know there have been some surprises, like session duration not necessarily at first being the same as developers anticipated. Through metrics and through application of design, does player behavior now align with what you anticipate, and can you maintain that?

AT: I think after a couple years, you understand more about player behavior through metrics. One way the metrics can definitely help you is to understand how players really behave, how they really think. Another way is you always ask your user to get qualitative feedback.

Quantitative measurement and qualitative feedback need to go hand in hand. Metrics can tell you how they're doing it, but not why are they doing it. Sometimes you may not be able to answer that -- like qualitative feedback from users sometimes doesn't really represent what they actually do.

That's what I find really fascinating. It's a well-known fact that what game designers might think is cool is not necessarily what users might like. But it's also true that potentially what users might think they want isn't exactly what they want.

AT: That's exactly right. If you ask users, "Would you want this thing?" If you just base your entire game design evolution based on strictly what your users tell you do, you'll probably fail. Any input has noise. Any data we collect has noise that needs to be filtered and cleaned up. With qualitative feedback, users also have noise that we can filter and then take that as input.

How do you obtain qualitative feedback? Is that just simply community interaction?

AT: Yeah. We have a very, very active forum, as you've probably seen. Community users usually give us feedback all the time.

They give us more feedback than we can process. So, there's never a lack of qualitative feedback from users, which is one thing that we really appreciate, because they are really passionate about our games, and they just tell us, "Hey, here's what I'd like you to change."

Do you think games can run indefinitely? Can FarmVille last forever, essentially, as long as you keep updating it? Or is there a certain saturation point?

AT: So far, it's been running for a year and a half, so we don't know. I guess we'll find out!

Popular television shows come to an end. MMO audiences drop off after years. It's an open question for the social game industry.

AT: It's an open question. And the one that we're also looking to find out, and we're also looking to expand our lifetime as much as users want us. So far, users don't seem to be complaining, so...

Retention is a real concern, obviously.

AT: Yes.

Have you honed in on like the right ways to retain users? Is it through content updates?

AT: Yes. Well, that's one of the basic things that must be done, but it's definitely nowhere sufficient. It's a basic thing that you need to have constantly updated things -- not only content, but also feature updates. Like I said before, like our farm game at launch had this many features [gestures, expanding his hands] it now has this many features. That's one of the reasons why you see the retention there.

And two, is to kind of be able to keep up the quality of games. Is it stable? Is it fast to load? Is it easy to play? Is all the content clearly labeled, to users? The basic user experience needs to be kept up to speed.

And third, it's just servicing on the community side. Are you listening to users? When a user complains, are you listening to them? Are you responding to them? Are you ensuring that there are no people trying to hack the game?

It's a lot of those things combined that eventually result in this thing called "retention". So, you need to do all these things right. I'm sure we could be doing a lot more things. Again, it's a matter of being in a young industry. We have limited resources.

Playfish has discussed having creative and metrics at the same level, so there's a feedback between them -- no one's telling the other what to do. Do you have a similar philosophy at Zynga?

AT: I think we are metrics-driven. It depends on what you mean by "creative". Like, what is creative? People's definition of creative is very, very different. We ask different people... What is creative to us? [If] people like it. Many times, to a game designer, what is "creative" is what is new. "What I think is creative."

I think we want to leave that judgment to the end users more. The end users will tell us what they like, what's creative. In fact, they'll give us a ton of ideas, too. So, I think that's where we differ. We want to drive as many things as possible through metrics and achieve, in the very beginning, not a balance, but a really, really integrated effort between metrics and creative. I think they can exist both in the same time. Very much so.

A lot of traditional game people sort of recoil from this idea, this sense that their creativity is being shut down, but I think if you look at it as, "I have some ideas. Now I can find out which one's right, which one people respond to," it's more appealing.

AT: Exactly. That's exactly right. Everything can be improved, because you're not doing a painting where everyone can just sit back and appreciate it. What you're building is a consumer product. Users have to use it, have to touch it, have to play it. As soon as that happens, you're in a different category than how creative an artist is.

And this is why I say game building is a craft; it's not painting. To build a cool looking bowl, first of all it has to be a bowl first. It has to be functional first. And different people have different ways of using that bowl, of looking at it. And you take that feedback and continue to improve it.

Everyone's creative. I have 10 million ideas if you ask me today. But whether or not users will like those ideas, well, let's ask the users. And metrics is a way to ask the user in the right way. They'll give you the answer to pick which creative idea, and once you've implemented that idea, how to keep iterating, keep on improving it.

I think in the traditional and console mobile industry... new releases are very, very expensive. New sequels are very, very expensive. But for us, we're Flash-based, PHP-based. We can change like that. That enables to continually improve an idea.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like