Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

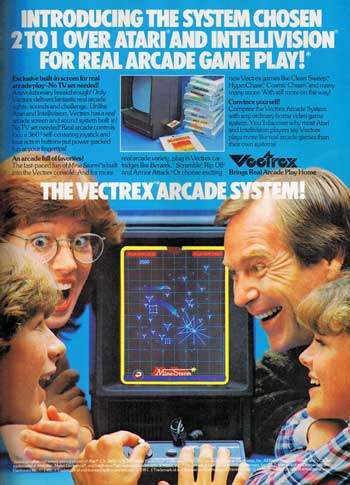

The 'ambitious and unusual' vector-based Vectrex console was one of the most intriguing game console failures of all time, and Loguidice and Barton continue their 'History Of Gaming Platforms' series by analyzing the rise, fall, and legacy of the cult '80s console.

[The 'ambitious and unusual' vector-based Vectrex console was one of the most intriguing game console failures of all time, and Loguidice and Barton continue their 'History Of Gaming Platforms' series on Gamasutra, started with the Commodore 64, by analyzing the rise, fall, and legacy of the cult '80s console.]

One of the most ambitious and unusual videogame systems ever released, GCE's vector-based Vectrex failed to win massive audiences, like the Atari 2600 Video Computer System (VCS) or the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) did. Nevertheless, the distinctive platform gained a cult following after being pulled from the market in 1984, two years after its debut, and now enjoys one of the finest homebrew development scenes of any vintage system.

The annals of videogame and computer history are littered with promising and ambitious systems that inexplicably flopped on the market, only later garnering the attention and passion of dedicated collectors and enthusiasts. However, the bulk of these obscure platforms are valued mostly for nostalgic reasons; only a precious few attract the time and energy of serious homebrew enthusiasts who continue to develop and release software for their favorite system long after it has disappeared from store shelves.

GCE's Vectrex is one such system. Debuting just two years before The Great Videogame Crash of 1984, it soon joined many lesser systems in the bargain bins of toy stores across the nation. The media was saturated with reports and speculations about the demise of the videogame industry, and the Vectrex was sucked into the vortex of bad publicity and uninformed opinion. Yet the Vectrex deserved and continues to deserve more attention than the hordes of cheap, me-too game systems and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial cartridges of the early 1980s. It is, after all, unique among programmable videogame systems, falling somewhere between a television-based console and a handheld in terms of design.

Yet the Vectrex deserved and continues to deserve more attention than the hordes of cheap, me-too game systems and E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial cartridges of the early 1980s. It is, after all, unique among programmable videogame systems, falling somewhere between a television-based console and a handheld in terms of design.

The Vectrex is a self-contained AC-powered transportable videogame unit that displays unique vector graphics on a built-in monitor. These vector graphics, which are essentially lines of light, have a timeless appeal that typical raster graphics, which consist of small pixels or blocks, can't duplicate. The Vectrex took the road less traveled, and was the better for it.

The system got its start in late 1980, when one of the hardware designers at Western Technologies (Smith Engineering), John Ross, had a light bulb go off -- or, to be more precise, a surplus one-inch Cathode Ray Tube (CRT). He took his idea to company head, Jay Smith, who had designed the ill-fated Microvision for Milton Bradley in 1979, the first cartridge-based handheld videogame system. Smith was impressed with Ross's idea, and his company shopped around a plan for a new type of handheld dubbed the Mini Arcade.

In early 1981, the Mini Arcade concept was offered to toymaker Kenner, who wanted a five-inch screen and a less portable design in which the CRT would sit on a stand with the controls on the bottom. However, Kenner soon canceled further development, so Western Technologies shopped the idea again. Western Technologies redesigned the system as a tabletop, and later that year General Consumer Electronics (GCE) licensed it for production -- though now with a nine-inch screen.

The system went through several name changes due to copyright and marketing concerns before assuming the now familiar moniker. After a very compressed and hectic hardware and software development period, the GCE Vectrex was officially unveiled at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show (SCES) in Chicago, June 1982, to positive notice, and released to the public in November, just in time for the holidays.

The Vectrex's base technical specifications were impressive. It used the speedier and more advanced Motorola 68A09 (6809) instead of the cheap MOS Technology 6502 8-bit microprocessor found in early Apple, Atari and Commodore computers. Likewise, its sound generator, a General Instrument AY-3-8910, supported a competitive three simultaneous channels of sound with a dynamic range of effects. The chip had been used in Mattel's earlier Intellivision (1980) and would show up in the Atari ST (1985) and other computer systems.

The Vectrex is a masterpiece of design. The control panel, which features a small self-centering analog metal joystick and four numbered action buttons, could be placed in a storage area at the bottom front of the console. The coiled cord would be wrapped once around the joystick, with the remaining length laid on top of the action buttons. The control panel could then be slid into the tabs at the bottom of the console and snapped up into place, creating a sleek forward-facing profile.

When the control panel is removed, seen from left to right is a three-inch speaker grille and the two joystick ports. Beneath the joystick ports are a button that resets the system and an Off/On/Volume Control dial. A horizontal cartridge port is located on the bottom of the unit's right side. A Brightness Control is on the top rear, with a permanent two-pronged AC power cord on the bottom rear. Openings for ventilation are present on the rear and bottom of the console. Also on the top rear of the unit is a recession for lifting and carrying the console, a design similar to what Apple would use in their first Macintosh computers two years later.

A rear view of the Vectrex showing the cartridge port on the left and recessed carrying handle on top. The unit on the right shows the control panel placed in its storage area.

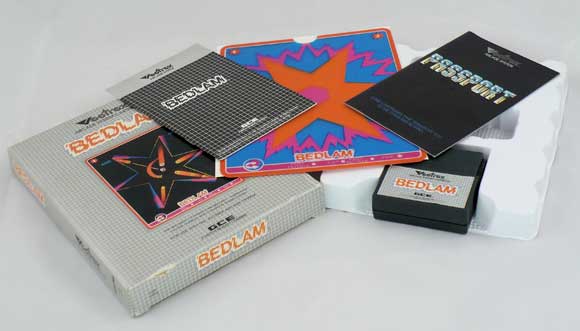

The Vectrex shipped in a large, rectangular silver-toned box with Styrofoam inserts. Inside the box was a single control panel, owner's manual, owner's club registration card, and the color screen overlay and instructions for the built-in Mine Storm game.

One obvious liability of the Vectrex is its black and white display. Even in the early 1980s, monochrome was seen as a serious limitation in a game system, no matter how innovative its display method might be. This potential deal-breaker was addressed with heavy gauge, flexible plastic overlays produced for each game. These overlays fit snugly into plastic grooves on the top and bottom in front of the monitor, and featured high quality color printing.

The overlays not only improved the games' aesthetics, but also provided simple instructions. The translucent, semi-transparent overlays also reduced the flicker inherent in vector displays. Since the overlays weren't designed until after a game was considered finished, they often frustrated programmers, since further code changes had to accommodate the position of an overlay's design elements. Nevertheless, the colorful overlays generally helped to enhance each game's presentation and remain one of the Vectrex's most iconic elements.

After a successful holiday launch, Milton Bradley took notice of the Vectrex and decided to buy GCE outright in early 1983, still maintaining use of the company name. With its strong financial foundation and worldwide reach, Milton Bradley was able to bring the Vectrex to parts of Europe by mid-year. Through a co-branding agreement with Bandai, the Vectrex also reached Japan as the Computer Vision Kousokusen, or Light Speed Ship.

"You need important resources to compete in a meaningful way in the video game market, and with Milton Bradley we will have that combination." -- Edward Krakauer, former GCE chairman, as quoted in the Boston Globe, July 15, 1982

At the SCES in Chicago, June 1983, Milton Bradley showcased a computer add-on. The computer add-on was a fashionable idea at the time -- the thought was to turn a "simple" videogame system into a full-fledged computer -- but few companies actually delivered on the promise, including Milton Bradley.

While a very early prototype was favorably previewed and did well in magazine benchmarks, the computer add-on was never finished and released. Other upgrades and accessories that never made it out of the development stage were a type of touch-sensitive screen overlay and a color Vectrex. While a color system would have been a logical next step, the engineering challenge proved too formidable for a mass market consumer device at the time.

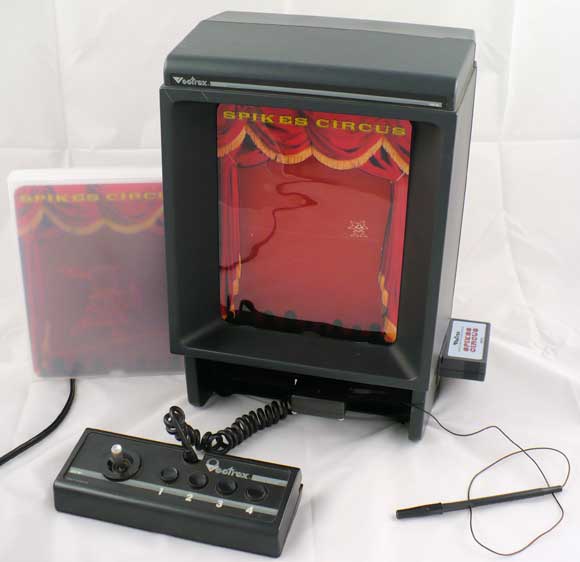

The light pen package, complete with Art Master

In early 1984, a light pen and 3-D Imager (headset) that simulated color were introduced and released in limited quantities. The light pen, which plugged into the second controller port and came bundled with the Art Master cartridge, allowed direct drawing and interaction on the Vectrex monitor. The 3D Imager came bundled with 3D Mine Storm and utilized spinning color wheels specific to a game to create one of the most convincing home 3D effects up to the introduction of more advanced shutter-based systems like those released in the late 1980s for the Nintendo Famicom (Japan only) and Sega Master System (SMS).

An artist's rendering of the Vectrex 3D Imager from the December 1983 issue of Electronic Games magazine

Unfortunately, despite a strong start and continued technological innovation, the Vectrex's success was short-lived. The Great Videogame Crash of 1984 had depressed the entire industry. Even after trying direct distribution, shuttering GCE operations, and aggressively cutting prices, Milton Bradley lost tens of millions of dollars over the life of the product line. In May of 1984, Milton Bradley merged with Hasbro, and the Vectrex was discontinued worldwide a few months later.

Callout: "We were badly hurt by Vectrex." -- George R. Ditomassi, Milton Bradley's Executive Vice President, as quoted in the Boston Globe, October 22, 1983

After product rights reverted back to Smith Engineering, an attempt was made in the late 1980s to resurrect the Vectrex as a handheld. Unfortunately, the pending introduction of Nintendo's GameBoy in 1989 put a practical stop to such plans once and for all.

In the mid-1990s, Jay Smith generously placed the entire Vectrex product line into the public domain, opening up legal, not-for-profit distribution. More good news came in 1996, with the release of John Dondzila's groundbreaking Vector Vaders, the second ever console homebrew cartridge (after Ed Federmeyer's Tetris clone, Edtris 2600, which was released in 1995 for the Atari 2600 Video Computer System.)

There has been a steady stream of increasingly impressive homebrew hardware and software since Dondzila's early work, with dozens of titles added to the Vectrex's catalog of releases. And there is no end in sight.

Since the Vectrex had many arcade-like qualities, the initial software strategy was to copy or license as many popular arcade games as possible. Atari and its classic vector arcade games like Asteroids (1979) and Star Wars (1983), were off-limits for obvious reasons, but Cinematronics, another top vector-graphics arcade game producer, was an ideal alternative.

In fact, the licensing agreement with Cinematronics was two-way, resulting in one of the first official home-to-arcade conversions in Cosmic Chasm, one of a number of solid Vectrex releases ready by late 1982. In Cosmic Chasm, the player's ship must navigate a maze of underground rooms and destroy a power structure in the center chamber. After a room is cleared of enemies, the player must drill through one of the exits. Once the center chamber is reached, the player needs to plant a bomb and find a way to escape before the maze explodes. Unlike most videogame systems at the time, which came packaged with a game cartridge, the Vectrex had Mine Storm built-in and accessible by starting the system without a cartridge. Mine Storm, obviously inspired by Atari's Asteroids, is a fine introduction to the system's capabilities. The player's ship rotates smoothly, with a subtle 3D effect.

Unlike most videogame systems at the time, which came packaged with a game cartridge, the Vectrex had Mine Storm built-in and accessible by starting the system without a cartridge. Mine Storm, obviously inspired by Atari's Asteroids, is a fine introduction to the system's capabilities. The player's ship rotates smoothly, with a subtle 3D effect.

The controller's buttons are put to good use, with escape (a random warp), thrust, and fire mapped to three of the four buttons. The sound effects, particularly the explosions, have great depth and go a long way towards creating an arcade-like effect. Unfortunately, for highly skilled players, there is a bug after the 13th level that could cause the game to reset itself. GCE issued a patched cartridge version, Mine Storm II (1983), to customers who complained to them about the problem.

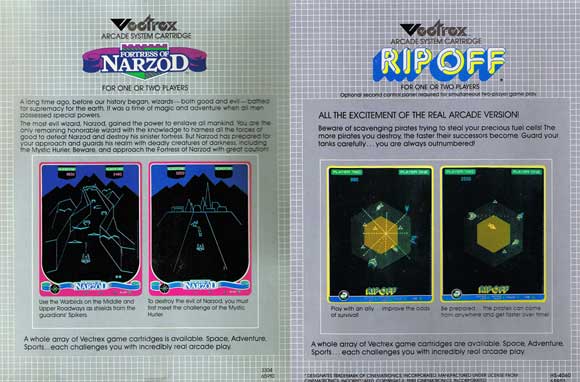

Direct arcade conversions included Cinematronics' Star Hawk (1982), which mimicked the trench scene in the original 1977 Star Wars movie and utilized analog control; Space Wars (1982), which was a two player spaceship duel inspired by the PDP-1 mainframe computer's Spacewar! (1962); Star Castle (1983), in which the player's ship tries to blast through a multi-layered rotating shield at the center of the screen; Rip Off (1982), a one- to two-player simultaneous game where the players use a tank to protect fuel canisters from other tanks; Armor Attack (1982), a one- to two-player simultaneous close combat game where the players use their jeeps to evade and destroy enemy tanks and helicopters; and Solar Quest (1982), where the player's ship must eliminate waves of enemy ships and rescue survivors before they fall into the sun.

Bedlam, showcasing a typical game's packaging, including box, manual, a color overlay, a catalog and a plastic tray for the cartridge.

Other arcade direct conversions included Stern's robot-filled maze-based shooter, Berzerk (1982); Namco's racer, Pole Position (1983); and Konami's side-scrolling shooter, Scramble (1983). Though somewhat similar in play to Sega's popular arcade game, Star Trek Strategic Operations Simulator (1982), Star Trek The Motion Picture (1982) was instead licensed directly from Paramount and considered an original property where the starship Enterprise battles Klingons and Romulans from a first person perspective.

Other shooters include Bedlam (1982), which has been described as an "inside-out" Tempest (Atari, 1980); Fortress of Narzod (1983), which requires the player to shoot through enemies in a fantasy setting, making great use of the system's scaling and depth-of-field abilities; Polar Rescue (1983), a first person perspective shoot and rescue game in a submarine; and Web Wars (1983), which casts the player as the "Hawk King" shooting fantasy creatures on various webs.

Though space games and shooters make up the majority of the Vectrex's game catalog, other genres made their way to the system. Clean Sweep (1983) is the obligatory maze chase game inspired by Namco's Pac-Man (1980). Blitz! Action Football (1982) and Heads-Up Action Soccer (1983) do uneven, but admirable jobs of mimicking the basic elements of the sports they're based upon.

Hyper Chase (1982) is a racer similar to Sega's Turbo (1981) and features analog control, while Spinball (1983) is a passable attempt at single screen video pinball. Perhaps the most intriguing original game is Spike (1983), which takes the Donkey Kong (Nintendo, 1981) platforming concept to an isometric perspective and spices up the action with speech samples that don't require any additional hardware.

The Vectrex's light pen came bundled with the aforementioned Art Master, which allowed for direct screen drawing and simple animation. Other light pen software released included AnimAction (1983), a more advanced drawing and animation program with included clip art, and Melody Master (1983), a music education and composition program.

"Vector graphics really do make a difference, and the strong line-up of games helps immensely." -- David H. Ahl in Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games, Spring 1983

The Vectrex's 3D Imager came bundled with the aforementioned 3D Mine Storm, which was essentially the same game as the original, only in color with the use of the included color wheel and with obvious 3D enhancements. Other 3D Imager software released included 3D Narrow Escape (1983), which featured fast navigation through a narrow fortress before a final confrontation with a boss character, and 3D Crazy Coaster, which challenged the player to keep the passengers' arms raised during the roller coaster ride as long as possible, while avoiding obstacles.

The box back for Fortress of Narzod, and the box back for Rip Off

As with most systems whose original shelf life was cut short, the Vectrex has its fair share of prototypes and other unfinished and unreleased software. These include Dark Tower (1983), an adventure game loosely based on the cult classic Milton Bradley board game; Engine Analyzer (1983), a utility program for use with the light pen; Mail Plane (1983), which was a type of flight simulator and the only true game that required the light pen; Pitcher's Duel (1983), a baseball game; 3D Pole Position (1983), which makes use of the 3D goggles; and Tour de France (1983), a bicycle racing game similar in design to Hyper Chase. Many of these prototypes and other unreleased software have since been made available by enthusiasts either as ROMs for emulators or on cartridges.

Purchasing a working Vectrex today from eBay will cost between $75 to $125 or more, depending upon condition and completeness. Getting a working controller can be an issue, and some controllers may no longer self-center. Servicing the controllers properly is extremely difficult, so a fully functioning and properly self centering control panel can sell by itself for up to $50 or more. Luckily, there are homebrew replacement options for those who know how to dig.

Most Vectrex systems exhibit a low level hum that can be distracting. This hum is known to be particularly loud on units from the first production runs. While an end-user can do some self servicing by placing extra shielding inside the unit, many enthusiasts simply accept the noise as a quirk of the system. Another issue that may befall certain Vectrex units is a loss of convergence, causing lines on the display to fail to properly align. As with system hum, these issues will bother some owners more than others.

Game cartridges are easy to find and generally sell for five dollars, or more depending upon rarity, which can increase the price exponentially. Many users hold out for games with the original overlays, though reproductions of varying quality are readily available. Original boxes tend to be flimsy and are often found slightly flattened. Light pens in the original packaging with Art Master can sell for up to $100 or more. Original 3D Imagers have sold from the hundreds into the thousands of dollars depending upon completeness.

Spike's Circus is one of a handful of titles to take advantage of hardware speech synthesis, with one optional peripheral, the VecVoxX from madtronix, shown plugged into controller port two. This particular model, VecVoxX Developer, supports several additional features, including PC interface, headphone jack and lightpen port. A homebrew light pen in a Paper Mate enclosure is shown plugged into the lightpen port.

Emulation of the Vectrex platform is robust and well-implemented on computers and select videogame systems. Emulators include M.E.S.S., ParaJVE and VecX, and legal ROM images of the original Vectrex games and certain homebrews are widely available. However, despite the convenience of emulation, the original hardware is really the only way to get an authentic experience. The unique characteristics of the Vectrex's display and overlays, as well as its accessories, simply don't transfer well to a standard PC or console setup.

Vectorzoa's 2006 homebrew, Spike's Circus, in action, with color overlay and packaging.

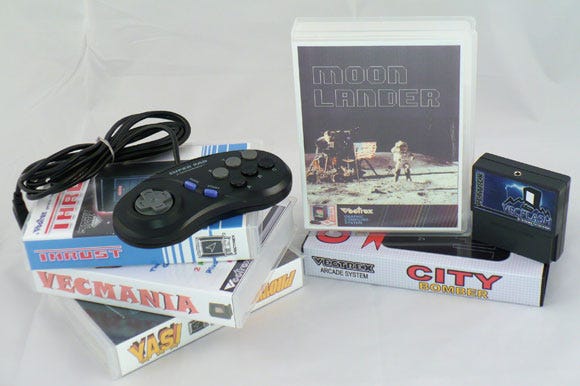

As mentioned earlier, the Vectrex's homebrew community is among the best in terms of quality, innovation and depth. Some of the most popular homebrew software includes Christopher Tumber's Omega Chase (1998) arcade shooter conversion of Midway's Omega Race (1981); Clay Cowgill's Moon Lander (1999), which is inspired by Atari's arcade Lunar Lander (1979); John Dondzila's All Good Things (2000), which features a collection of several quality games; Alex Herbert's Protector and Y.A.S.I. (2003), with the former a Defender (Williams, 1980) clone and the latter a VecVoice/VecVox speech-enhanced Space Invaders (Bally Midway, 1978) clone.

There's also Craig Aker's Nebula Commander (2005), a real-time strategy game supporting one or two simultaneous players; Revival Studios' Debris (2005), a vertical shooter that features simulated bitmap graphics instead of the usual vector; Alex Nicholson's Star Sling (2006), a shooter that supports analog controls and two player simultaneous action; Fury Unlimited's 3D Lord of the Robots (2006), which is the first new game for use with the 3D Imager; and Revival Studios' Vectoblox (2007) puzzle game. There's even VecOS, which upon its future official release promises a Graphical User Interface (GUI), bitmap display, sound player and VecOS BASIC, a fully embedded Vectrex BASIC editor and interpreter.

A collection of homebrew items, including a converted Genesis controller and Vecmania (1999) from John Dondzila, Thrust (2004) from Ville Krumlinde, Protector and Y.A.S.I., Moon Lander, City Bomber (2007) from Andy Coleman, and VecFlash from Richard Hutchinson, which allows ROMs to be transferred and run

Homebrew hardware on the Vectrex is just as exciting. Some highlights include a variety of adapters and controller conversions that make use of Sega Genesis and Sony PlayStation controllers; Richard Hutchinson's series of increasingly sophisticated add-ons that allow for, among other things, speech synthesis and ROM usage; low cost replacement light pens; and, perhaps most impressively, a low cost and 100% compatible 3D Imager replacement from madtronix.

While the madtronix 3-D Imager offers a slightly greater viewing angle than the original GCE model, the base display technology, like most 3D/headset systems, is still too uncomfortable for most people to use for anything more than brief play sessions. Shown to the bottom left is a special multi-cart (games are selected by modifying jumper combinations) that came with this edition of the Imager. Shown to the upper right is the special edition of 3D Lord of the Robots with laser engraved box cover.

The clever homebrew 3-D Imager from madtronix

All in all, a working Vectrex is an excellent find for any collector of vintage systems. It's a unique platform with many features that aren't found anywhere else, and its collection of software, both old and new, put its innovative hardware design to excellent use.

Release year: 1982

Resolution: 330 × 410

On-screen colors: Vector Monochrome

Sound: Three channels, mono

Media format(s): Cartridge

Main memory: 2K

Visuals: 3.5

Audio: 3.0

Control options and quality: 6.5

Features, expandability, and add-ons: 6.0

Software diversity: 5.0

Software density: 4.5

User experience: 10.0

Initial popularity: 2.5

Overall score: 41.0

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like