20 years later, David Brevik shares the story of making Diablo

Speaking at GDC in San Francisco this week, Blizzard North cofounder and Diablo creator David Brevik spoke to what went right -- and wrong -- in the making of the influential action RPG.

David Brevik helped cofound Blizzard North over twenty years ago, and played a pivotal role in the design and development of the studio’s influential hit Diablo.

The game was released at the end of 1996, and to celebrate its 20th anniversary Brevik took the stage at GDC today to deliver a postmortem look back at his work on the game.

“The original concept was something I came up with in high school,” said Brevik, who went to school in California’s Bay Area and got the idea for the game’s name from local peak Mt. Diablo. “It’s all I’ve ever wanted to do, make games, and even in high school I was thinking about what kinds of games I could make and what names I could use.”

The original concept for Diablo, says Brevik, was more of a traditional party-based RPG, turn-based and heavily influenced by his early love of games like Rogue and Nethack.

But right out of college, he wound up working at a digital clip art company that eventually went under; when that company went under, a few survivors went on to launch their own company, named after a secret project the clip art company had been working on: “Project Condor.” Thus, Condor the game company was born.

It was there that Brevik put together a design document for Diablo, describing it as a turn-based, single-player DOS game that would have expansion packs -- like booster packs for Magic the Gathering cards, whch were big then. It also had permadeath, says Brevik. “That was a big feature of roguelikes, so that’s why I wanted that."

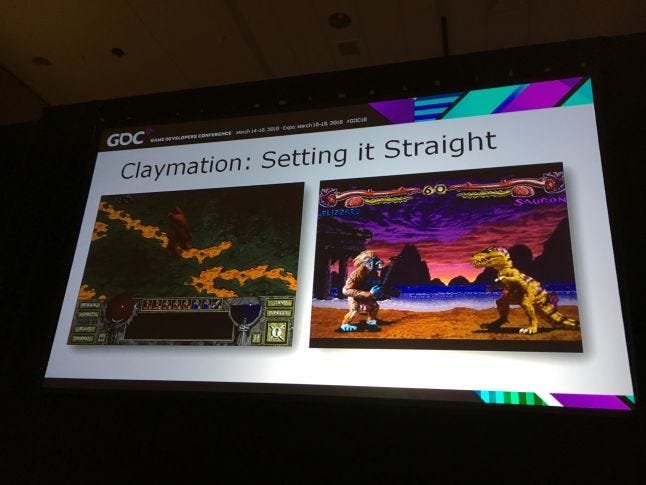

It was also, as is sometimes rumored, originally designed with a “claymation” art style -- kind of.

“It wasn’t just claymation,” said Brevik, noting it was actually inspired by the look of contemporary arcade fighting game Primal Rage.

“I loved the way Primal Rage looked in the arcade," said Brevik. "It used stop-motion for all its characters and graphics," and Brevik wanted to use a sort of stop-motion art style for Diablo. But once he learned how expensive and time-consuming it would be, the idea was shelved.

How Justice League Task Force brought Blizzard North and South together

But since Condor had to stay in business, it was planning out Diablo while it was also working on some other sports and licensed games, including the Sega Genesis game Justice League Task Force.

Brevik remembers taking the latter game to show it at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, and finding an unexpected comrade-in-arms in developer Silicon & Synapse, which would eventually become Blizzard Entertainment.

“We show up, and we have our game on display, and we look over and...there’s another version of the product, for Super Nintendo!” Brevik said.

Condor had no idea there was a Super Nintendo version of Task Force being made (because the publisher had never bothered to tell them) and yet the two games were still “strangely similar.” Condor wound up talking to the developers, Silicon & Synapse -- who also happened to have dreams of striking out on their own and making their own original PC game, just like Condor had been trying (unsuccessfully) to do with Diablo.

“We’d been trying to pitch this game idea to a whole bunch of people...and they have said no, RPGs are dead. There is no way we are investing in an RPG,” said Brevik.

But after Silicon & Synapse became Blizzard and made Warcraft, they came back to Condor and heard the studio’s pitch for Diablo. They liked what they heard, and offered to publish the game.

“We were very excited, so we signed a contract to do Diablo,” remembers Brevik. The studio then had to figure out what, exactly, this turn-based isometric game it had been thinking about for so long would actually look like -- and how it would be angled and rendered on-screen.

“This was not easy back then...I kind of took a screengrab of X-Com, and we just took that, and put it right into Diablo,” said Brevik. “So the actual tile-square basis -- the same shape and size -- is exactly the same in X-Com and Diablo.”

So in a sense, says Brevik, the look and technology of Diablo is all based directly on a screenshot of X-Com.

Brevik also remembers that the decision to make Diablo real-time, rather than turn-based, as a controversial one. He said that, despite rumors to the contrary, it's not true that when Condor first pitched the game as a turn-based game, Blizzard said it was great -- but that it had to be real-time and multiplayer. That came later, after development of the game had begun in earnest.

“Eventually, Blizzard South, they approached us and said ‘well, we’d really like to make this a real-time game,’” recalls Brevik. At first, he says, he was adamantly against it -- he loved classic turn-based dungeon crawlers like Rogue, and he didn’t want to give up turns because giving players time to agonize over their decisions between turns could create so much "delicious" drama.

“‘Yeah,’ [Blizzard South] said, ‘but real-time will be better,’” said Brevik. So Blizzard North eventually put it to a vote, “and I voted no, but everyone else voted yes, so I said I guess we can do this.”

So Brevik called Blizzard South to say yes, we can do this, but we need lots more time to overhaul the game -- and also, another milestone payment.

“They agreed to that, and I went ‘yesss,’” remembers Brevik. “So I sat down on a Saturday afternoon, and in a few hours I had it running [in real-time.]”

"That was when the APRG was kind of born"

At that point Brevik fondly recalls clicking his mouse, watching his formerly turn-based warrior walk across a room in real-time and smash a skeleton, “and I remember saying out loud ‘oh my god, that was awesome!’”

“Sure enough, that was when the ARPG was kind of born,” said Brevik. “It was an amazing moment, and I was lucky enough to be there.”

During Diablo's development Condor became Blizzard North, in part, remembers Brevik, because of the company's less-than-stellar business sense.

“We were so excited to do Diablo, that we signed the contract [with Blizzard] without realizing we’d just agreed to do Diablo...for $300,000,” said Brevik. “We have 15 people in this studio, so….are we just going to pay them $20k a year to do this? Also, how are we gonna pay for this office space?”

But they really wanted to make Diablo, so Condor went looking for more work to bolster its finances. They found 3D), and signed a contract to make a football game for the console -- for almost $1 million.

“That helped,” said Brevik. “That helped a lot.” Even so, the company didn't get all that money up front and was still struggling, day-to-day, to pay its staff and maintain its operations.

“Then at one point, Blizzard South came to us and said ‘hey, we’d like to acquire you guys,’” Brevik said. “That was a big relief, not having to worry about making payroll anymore. But 3DO got wind of it, and didn’t like the idea -- so they stated making their own pitches.

"3DO was offering us twice as much money, and we turned them down"

“So this bidding war started, between Blizzard and 3DO,” said Brevik. “3DO was offering us twice as much money, and we turned them down, because we felt that Blizzard really got us, and got the game. And we were so close in company culture and beliefs that we turned down twice as much money to get bought by -- and become -- Blizzard.”

Incidentally, Brevik recalls that late in ‘96, as Diablo's development was in crunch mode, a businessman named Sabeer Bhatia came to Brevik and said, basically, “I’m going to make email on the internet….I’ll give you ten percent of my company if you let me have a room in the back [of your office] to work.”

Brevik said “No way, this doesn’t make sense! Email, on the internet? I already have email on the internet!” And with Blizzard North crunching away on Diablo, Brevik remembers telling Bhatia he couldn’t spare any room to work on his company.

Bhatia’s company came to be known as Hotmail, which went on to be worth roughly $400 million. So Brevik would have had $40 million worth, which in today’s dollars (he estimates) would be roughly $280 million.

On the plus side, developing Diablo gave rise to Blizzard’s Battle.net, which was borne out of Blizzard North but primarily developed at Blizzard South. But Diablo didn’t have multiplayer modes - or code -- for most of development, so in the last months of development a team from Blizzard North had to actually move down south to work with Blizzard South on getting Battle.net support built into Diablo, and Brevik says the studio was completely unprepared for how quickly -- and badly -- cheating became a problem in the game.

“We knew people were going to be able to hack, or cheat,” said Brevik, but the studio figured it would be isolated incidents. “Then the game came out, and instantly we were like ‘oh my god...they can just upload the cheats and EVERYBODY can cheat! I didn’t even think about htat!”

Looking back, Brevik recalls this was one of the biggest “egg on our face” moments of Diablo’s livespan, and it srongly drove Blizzard to revamp the client-server architecture for Diablo II.

"I'm gonna say it: Battle.net ran on one computer"

Also: “It’s not much of a secret anymore, I don’t know if I’m going to get into trouble if I say it, but I’m gonna say it: Battle.net ran on one computer,” said Brevik. “Because we had people directly hooking up with each other, we didn’t have to carry a lot of bandwidth...we just had to make these connections.”

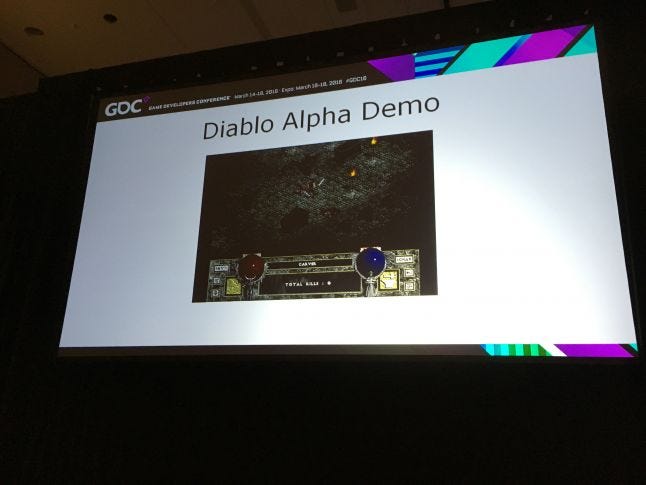

Brevik then showed a brief snippet of a Diablo pre-release alpha demo the company shared via PC Gamer demo discs in November of ‘96, one of which he’d managed to find in his own home.

“One of the things we didn’t like about RPGs at the time is they all had like 25 minues of character creation before you could get into the game,” said Brevik. And Blizzard North had a lot of love for the menus in Doom, so they designed Diablo’s UI with a lot of thematic inspiration from id’s work, to meet the “mom test” -- “could my mom play this?” Brevik said. The idea was to make something that players could start playing as quickly as possible, with minimal hang-ups.

Speaking of UI, Brevik noted that the map of Diablo was inspired directly by the minimalistic automap of Dark Forces, and that "we invented the hotbar some time in the last 3 months of the project."

Before that, said Brevik, there was one slot in the lower-left corner of the screen where players could put potions, but otherwise, you were straight out of luck. The studio also almost got rid of the “right-click to use skill” mechanic (requiring the player to bring up the skill book and click on a skill each time to use it) and almost put cooking and eating mechanics into the game, right at the end of development, but ultimately didn't have time.

"The end was really, really rough"

“The end was really, really rough; we crunched for 8 or 9 months,” remembers Brevik. “My wife was pregnant at the time; the baby was due in late December...you can see where this is going.”

Around December 10th, recalls Brevik, his wife called him at the office and said “I’m having contractions. It’s go time.”

The studio was already in trouble, since it had tried -- and failed -- to have Diablo ready for Christmas of ‘96. But it wound up shipping on December 31st, and the contractions proved to be a false alarm -- Brevik’s daughter was born January 3rd, days after his game.

“We were super, ultra-focused on making this thing great, and I think it paid off in the end,” said Brevik. “Crunch is never fun, but sometimes, at least for myself, I think it’s a necessary evil.”

(Incidentally, Brevik noted that crunch on Diablo II was even worse -- about a year and a half straight. "It was the worst crunch in my life," he said.)

Here’s a weird bit of trivia about the game: Brevik remembers running a contest after Diablo launched, offering to pay $100 to the first player who could kill Diablo. Shortly thereafter a player used a health-swapping skill to run down to the final boss, swap health with him, nearly die, swap again and slay him.

“We promptly yanked that skill out of the game,” said Brevik. Presumably, Blizzard North also paid the player his $100.

Another tidbit of design trivia: “Deckard Cain’s name was actually a contest..as part of a PC gaming magazine contest, people could send in name suggestions to get their name in Diablo,” said Brevik, in response to a question from the audience about where the Diablo character got his name. “Some guy sent in the name Deckard Cain, I don’t know if it’s made up or not, but we were like ‘Damn, that’s badass. We’re gonna use that!’”

Read more about:

event gdcAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)