"Green River" - How San Andreas Shaped my Mentality as a Designer

A retrospective on how my experiences with the game, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, molded my aspirations as a game designer.

When Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas was released in 2004, the game was rhapsodized at best, admonished at worst. To some, the game was a symbol of the increasingly violent nature of games – complete with trite bloodshed, and to others its immersive depth was a hopeful indicator of the game industry’s direction for the foreseeable future. It was a mature game for a rapidly maturing games landscape.

I first played San Andreas when I was twelve – not even a remotely appropriate age for a game that was regularly touted in the media for instigating criminal behavior. As someone who grew up in the age of Call of Duty, the general design of most titles was regrettably linear. Midtown Madness was the greatest extent of freedom I had experienced in a game, allowed to speed through miniaturized cities rife with invisible walls and boundaries at my leisure, and as a result, the moment I sat down to play San Andreas I was instantly captivated by the sheer freedom I was given as a player. Suddenly I was able to roam a reimagined conglomeration of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Las Vegas - able to explore every alley, nook, and cranny from land, sea, and air – all to the tune of Bowie or Credence Clearwater Revival.

My early experience with the game was much like Special Agent Dale Cooper first entering the picturesque Pacific Northwest in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, enraptured by Douglas Firs and cherry pie, unaware of the morally questionable circumstance saturating the town he investigated. I migrated unguided from location to location, from vehicle to vehicle, encouraged by the thrill of discovery in scouring the handmade landscape, oblivious to the violence that permeated the core mechanics of the game, only to discover it as I delved deeper and deeper into the immersive experience of traversing the game world.

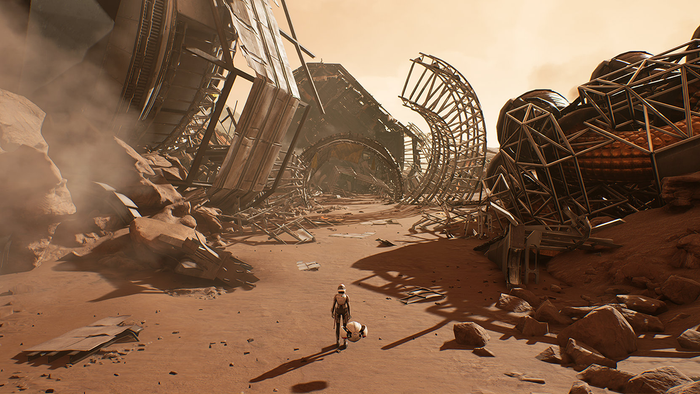

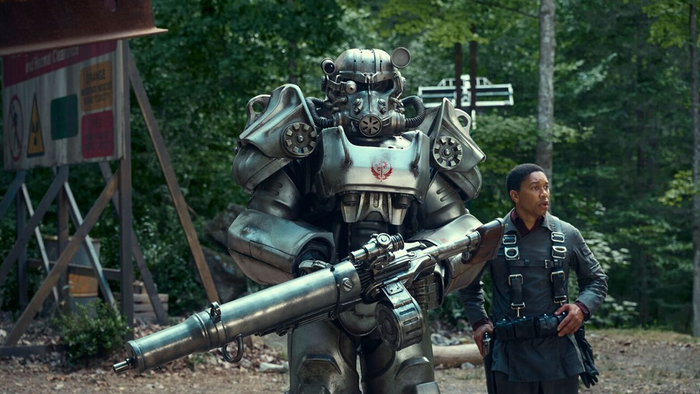

Now, it’s important to keep in mind that my parents never condoned my ownership of this sort of game – my copy was purchased for me by my brother and hidden away in a slide-out drawer behind my keyboard. Predictably, it was impossible for me to appreciate the game for what it truly was until I grew older. I gradually became accustomed to the scathing social commentary that travelled over the virtual airwaves of WCTR, and the bevy of pop culture references, homages, and satire that characterized the style of the game. But, most importantly, I began to appreciate the sandbox for the realm of experimentation that it was. As time passed, I became fascinated with open world games, trying dozens from Assassin’s Creed to Just Cause, each with its own character, from historical to explosive, yet all failed to grasp my attention as relentlessly as Grand Theft Auto.

Ingrained into the very woodwork of San Andreas was a drive for agency, exploration that stretched beyond the bounds of the shapes rendered on my screen. Despite any traditional or official support, the game had a thriving and wild modding community that, fed by its players, pushed the game to overgrow the boundaries of Rockstar’s vision. A veritable social structure, the community could be broken down into cliques – those who made cars, who built missions, who built the weird and wonderful and everything in between on a broad spectrum ranging from idolized to controversial, and just as with any community, no matter how welcoming, there existed a dark underbelly. Despite the hailstorm of controversy that surrounds each Grand Theft Auto game, San Andreas still manages to stand out – having been temporarily taken off of the shelves of every store in America due to an explicit mod dubbed “Hot Coffee.” However, the nature of the mod isn’t the point; as a result, the modding community became more exclusive and discerning afterwards, for a multitude of reasons, from additional security measures built into the game to a desire for accessibility. In a sense, every mod for the game from this point on was its own personal brand of coffee, with a specific consumer base and unique flavor it contributed to the player experience.

It was from this competitive climate a mod named MultiTheftAuto arose. For the uninitiated, MultiTheftAuto, or MTA for short, was a revolutionary mod developed for GTA Vice City that allowed players to host dedicated servers where they could script their own game modes and functions into the game world. When a new codebase was developed for San Andreas, the game began to spawn ambitious RPGs - new landscapes of exploration, where only half the game took place in a virtual space – the rest was constant negotiation, planning, and fighting for control of the forums these servers occupied. These societies remained true to the spirit of the world they inhabited, breaking off into clans of criminal empires, elite tactical squads, and cynically entrepreneurial corporations. Immediately there was a need for both teamwork and rivalry if one wanted to stake a claim in the finite space of the game world and control the dynamic economy built into the game. With servers full of hundreds of people, emergent stories were entirely player driven and supported by a skeleton framework of mechanisms that kept us in the confines of a marginally realistic universe, allowing us to set goals based on the needs of the people we surrounded ourselves with. Although the original game came out in 2004, I played on RPG servers throughout high school, almost a decade later. I could say that, in a way, it was because I felt restrained. In English, over a week we’d go over a single act of Shakespeare. These servers evolved so rapidly, I could orchestrate a gargantuan business deal on Monday and see it dissolve by the same Friday. Organizations rose and fell while I slept. In a sense, this overly dynamic social landscape was a condensed and exaggerated representation of our intensely interconnected generation and rapidly globalizing society, where everyone vies for power, no man is an island, and collaboration is the only way to stay in competition. It was a complex and fluid social framework that participating in was significantly more fulfilling than the rigid and divisive social landscape of a 2000 person school.

That’s why, when I first sat down to play GTA Online, I was thoroughly disappointed. I was disappointed that I could only interact with 16 players at once. I was disappointed that every single activity was structured with a lobby and strictly defined objectives. I was disappointed the world around me was merely a model, not a simulation, in everything from the people around me to the stock market. Most of all, I was disappointed that all of these combined made the player agency I held so dearly suffer. That isn’t to say MTA was perfect, in fact it was far from. The economy was overinflated, there was constant debate on how much power groups can and should be given, and there was a severe rift between the poor and wealthy – but what made MTA significantly more entertaining was a dynamism that simply could not survive in the structured GTA Online.

As a result, San Andreas and MTA molded what I felt all MMOs should aspire to be. Foundationally, letting players loose in a massive game world is a necessity, and keeping them in a persistent world is a priority. The moment a group of players is virtually separated from the rest of the gamespace, this simply creates another limiting factor to the creation of a social structure conducive to alliances and collaboration. In order for truly emergent stories, virtually any element that is controlled by the system must not only be able to be influenced by players but must be a simulation as opposed to a model. I realized that what drives a great MMO is not the environment the developers create, but the social framework this environment enables - and the scenarios that arise from the combination of the two that are unique to each and every player. Agency, for me, is what drove exploration, from my first experiences with the game to my involvement in the creation of a virtual community, and I’m sure it is the very thing that drove hundreds of thousands of other players to renovate the game to their own liking. Agency is what allowed us to search for an experience that was unique to us – an experience that in a sense was, excuse me, a damn fine cup of coffee.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like