Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In an effort to better understand the making of the game's striking narrative, Gamasutra chats with Remedy narrative designer Brooke Maggs about her work crafting Control's eerie setting.

Last month Remedy Entertainment launched Control to the world, its latest game in a lineage of narrative-driven experiences, from Max Payne to Quantum Break.

Protagonist Jesse Faden is trapped inside an ever-shifting environment called The Oldest House, looking for answers about the past and current events in the Federal Bureau of Control, an entity dedicated to studying anomalies.

In an effort to better understand the making of the game's critically-acclaimed narrative Gamasutra chatted with Brooke Maggs, a narrative designer at Remedy who has previously worked on The Gardens Between, Florence, and Paperbark, about her experience working to craft Control's eerie setting.

Working in a new IP of this scale opened up an extensive playground for experimentation, and posed some new challenges for the team at Remedy.

Maggs says that previously the studio focused on fairly linear games, where players just followed the story through, getting to know the narrative and engaging in combat from time to time. But this time it was different, since the design of The Oldest House encourages players to plot their own routes through the world. Along with the main story path there are side missions, videos playing on TVs, and audio logs to find, all of which had to be wrapped up neatly alongside Control's core narrative.

“We had to make decisions about what key concepts to introduce in the main story, and how to build out the world in the side missions. An example [for this] is getting to know more about characters just by interacting with them, doing favors and helping get things under control with the Bureau,” Maggs explains, noting that the Control team are counting on curiosity driving players to seek out more narrative content in the corners of the game.

“They can choose just to power through the main missions or they can follow it during side missions... and not a lot of the these are actually super clear either, so it encourages discovery,” she adds. “If you're curious about a red light in a room, that will link to something. And that's really nice too. We're encouraging players to be curious and then rewarding that curiosity with narrative, as well as some [character] abilities on the side, things like that.”

Control also relies on environmental objects (think: documents and tapes lying out on desks) to give players the backstory of characters and small details of the world in short doses, but making them available in a game punctuated by room-destroying combat proved to be tricky, considering Jesse can levitate and use telekinesis to rip fixtures off walls, lob desks or other heavy furniture, and generally make a mess of the place.

Maggs explains that, because everything is reactive and dynamic in the environment, they had to plan how to avoid game design pifalls like making a single table in a room static and immovable because it has a valuable narrative document on it. Instead, they worked to place those narrative bits in parts of the game world that weren't likely to be disrupted, but were also easy to find.

Some of the bigger narrative payoffs were instead transmitted through live-action video of actors that plays during the game (and can also be accessed from an in-game menu), minimizing the odds of players being distracted by combat.

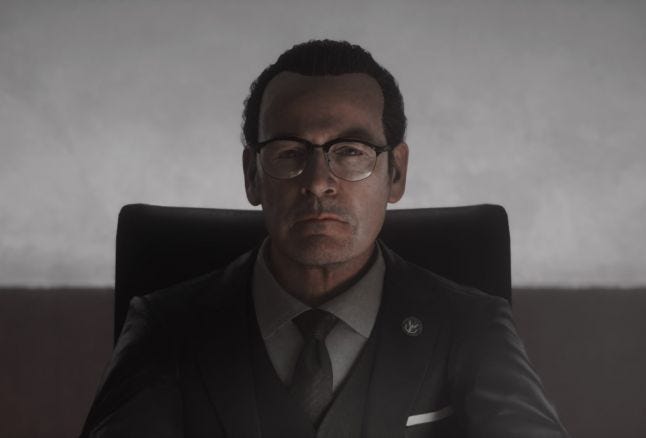

“So when [Director Zachariah] Trench appears to Jesse, that's happening while the player is still moving around the environment, so we don't actually take control and show a cinematic in that point," adds Maggs. "we leave the freedom [to] the player so they can still look around."

Though Maggs didn’t write them specifically, she was also involved in the design of Control's audio logs from the beginning. The Control team had a spreadsheet where they would decide what they wanted to include that wasn’t already covered in the main story, and then go from there. This covered topics like everyday life in the Bureau, objects of interest, and other quotidian day-to-day happenings in a paranormal environment.

Notably, Maggs says the team spent significant time ironing out the reason why characters would record specific audio logs in order to add to the realism, a concern that hasn't been as significant in some of her prior work.

“[The setting] was really interesting because the world in Control, I guess has a different purpose? So, the world in The Gardens Between is very metaphorically, because the whole fantasy was created by [the characters] memories’ together, and everything that you were doing was uncovering what had happened in this friendship. Whereas the world in Control, first and foremost [during] development we looked at questions like ‘what is the Oldest House, how does it work, how was the Bureau?’ and this was actually creating a realistic narrative world in a much larger scale.”

She compares it to Florence, Mountain's 2018 mobile hit about the main character’s relationship and the ways it's reflected in the micro-world arounder. But in Control,� the world is much larger and can be considered a character in itself; according Maggs, the same applies to the Oldest House.

On paper, this process involved asking herself questions of what stories each location could tell, about both when the player is traversing such spaces and what happened before. Something as mundane as the game's safe rooms, for example, required a lot of brainstorming beforehand.

“We've had some things put in the safe room by the level designers and we were like ‘that's a great idea but realistically these would not be in a safe room,” says Maggs while laughing. “All of that was awesome. I remember sitting with environment artists and level designers talking about how to put more of the story into the world.”

Often, these artists and designers would come up with better ideas than the narrative team once they actually had the narrative context for these spaces. “That's their art form, telling story in the environment and thinking that through," adds Maggs. "Environment artists know exactly what works, what color to put on the floor in a certain sector, because there was a design document for that... I mean these people don't mess around. Working with people who have that level of detail to the world was super cool.”

According to Maggs, creativity and attention to detail is common at Remedy. “The Threshold Kids”, a live-action puppet show presented in Control, was hand-crafted by a cinematic designer. The idea came from the narrative team, but it was the designer who actually built the puppets himself, using a studio downstairs as a set to record the scenes present in the game.

Maggs’ role intertwines with basically all other sectors at Remedy, as she focuses on the overall story and the player's experiene of it. While writers have to focus on characters, thinking about the words they use and how they articulate them, or authoring a backbone for a mission and how that’s going to work, Maggs’ job is to bring together all the people who have touched said mission. This involves sound design, lighting, VFX effects, level design, environment art, animation, and writing.

“We all go through a side mission together and say 'Jesse needs to say something here, we need an animation of her opening a door, we need a sound effect for the door opening, we need lighting on the door so people can see it’ and that's [usually] what I do," Maggs explains. "Then, I follow up and answer questions about the story that might help...that's where we come in, sort of like a walking dictionary for the world [of Control].”

Some of the new skills Maggs picked up while working on Control involve working with actors, recording and pacing dialogue, and getting people inspired to contribute to the story.

“When we were sort of saying like 'we've got this narrative idea’ and people would be 'that's very strange, what are you doing?' we were like 'well, bear with us!'” she tells Gamasutra. “I think I've learned a lot about championing the story and helping guide people to sort of all have the same idea of something in their heads, which is a challenge. I've also learned about attention to detail in a world, especially from Sam Lake. He really thinks through everything meticulously, and I thought that's the kind of craftsmanship that comes from years of working in narrative games. So that was really incredible.”

To anyone wanting to get into narrative design, Maggs’ advice is to understand story and story structure. She adds that her background in writing and editing has been really helpful. Even if she doesn't directly do those things in her job, she has done a lot of writing regarding design documents. All of it has to be clear to convey an idea, and whether that's fiction or non-fiction, it’s an important skill to have.

“I'd also encourage people to play games that have a strong narrative design to them, like Her Story, which is a good example of a story that's told with the way you interact with the game. Understanding game mechanics and what those make players feel it's important,” she says. In addition, thinking and looking at ways other media tell stories -- that it’s not to do with words but rather images, color, and sound -- is key. Maggs mentions Journey as a prime example of this, since there is no text or speech in the game, and how they examined that aspect when she was working on The Gardens Between.

“Pursue what you're really interested in, because narrative design can be a lot of different things, from interactive text games to puzzle or action adventure," she concludes. "Find the games that you love, dissect them and see how their work.”

Read more about:

Horror GamesYou May Also Like