C.H.A.I.N.G.E.D. is a multi-dev project where every in-game decision is a brand new game

"It's super inspiring to be given an unfinished story in the form of multiple games."

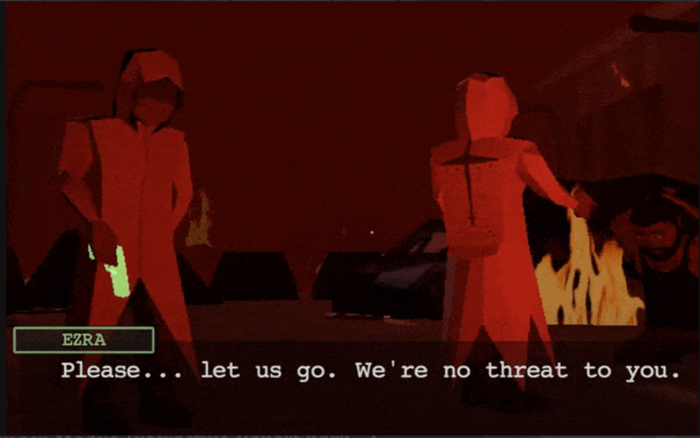

C.H.A.I.N.G.E.D is a game of choice that takes place after the Antichrist has risen and the world has ended. Its dozens of decisions are each an individual game made by a whole new creator, though, capturing games across many genres and styles with each choice the player makes.

Game Developer spoke with Adam Pype, developer of one of the choice games and the organizer who pulled so many developers together for this ambitious project, as well as several of the developers who worked on it, discussing the approach they took to organizing so many creators of different skill levels, what thoughts went into making something surreal yet coherent when working with all those creators, and what it felt like to see that creation fully come together.

CHAINGED is a game of choices that combines the work of several different horror developers into a single work. What inspired you to put this project together?

Pype: CHAINGED is a direct follow-up to CHAIN, which I organized and released back in 2020. CHAIN was inspired by Experiment 12 by Terry Cavanagh (who later on actually ended up making a game for CHAINGED). That game had each developer make a follow-up of sorts to a game made by the previous developer, but from what Terry told me, they would play all of the games that came before them and then make a new one. CHAIN was slightly different as it was more of a game of Telephone. Each developer would only get to see the game before them and then try and make a follow-up to that. This ended up with a pretty messy storyline, and as a group, we thought that we wanted a more consistent story for the next one.

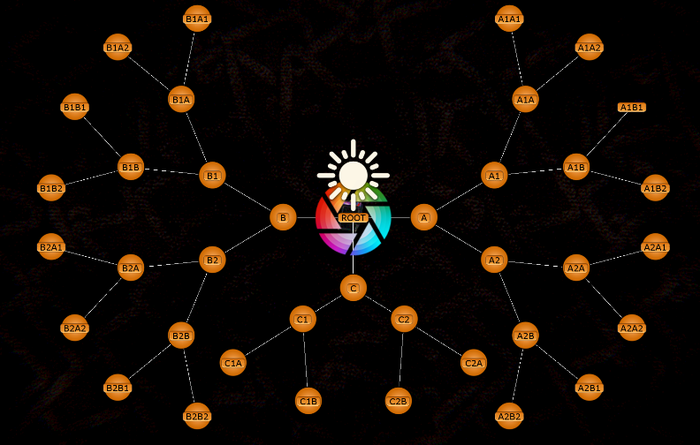

To make it worthy of a follow-up though, I didn’t want to just repeat whatever we did last time. So we came up with the idea of having branching paths—every game would end on a choice, which would then each be a new game. To keep the story more consistent, developers could play all of the games that lead up to their games, but you still couldn’t look into neighboring branches, to keep some air of mystery (which made it easier to organize).

As the project was meant to be several different games tied together, what sort of direction did you give each of the developers? Did you give little or no direction, and why? What effect did you hope this would have on the finished works?

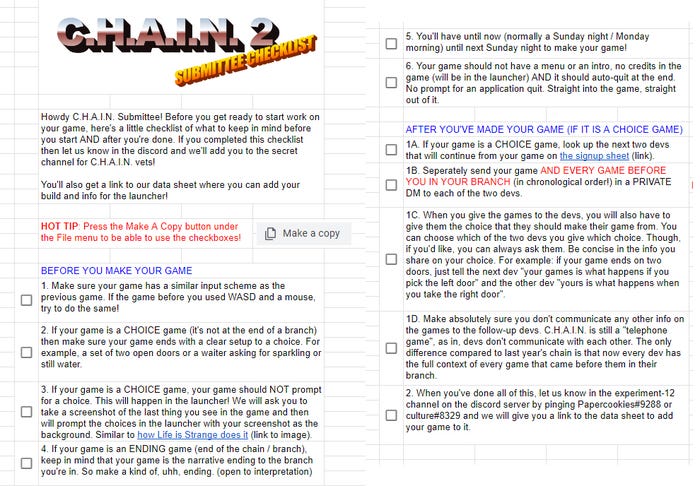

Pype: For a project of this scale to work, things needed to be straightforward and hands-off. For the last one, I did all the organizing through Google Sheets, and I did the same thing again this time around. There was a first sheet where people could sign up. Once that was filled, I had an idea of how many games we would be doing, so I made a branching diagram where the people who signed up could pick which part of the branch they wanted to make a game for. Giving the dev the option to make a choice game (a game that ends on a choice) or an ending game was pretty important to me. After that, I gave them yet another sheet with specific rules and instructions.

The thinking here was that having a very clear set of instructions would take away a lot of organizational work for me. I wanted devs to basically do everything themselves, even up to sending the game to the next person. Once you completed this checklist, you got access to a secret channel on the Haunted PS1 discord where you could chat with others who have submitted their game. I think it was very effective in the end. Without this, there was no way I could’ve handled a project with more than 50 people involved.

I’ve had some people ask me why I didn’t give any direction on the games themselves. My reason is that I wanted it to be very accessible for anyone to make a game for this. There was no curation of devs involved as well. I think having devs of different skill levels makes for an interesting mix of games. The most important thing is I wanted it to be fun to make. Having it be very QA-ed and player-friendly really took a backseat as, to me, it was more important that it got done and that the people who worked on it were happy. As an extra bonus, we got some really weird games out of it, which I think is good, actually.

What challenges came from tying so many varied works from different developers into a single title? Were there some systems you asked the developers to put into place so it would be easier to bring everything together, mechanically?

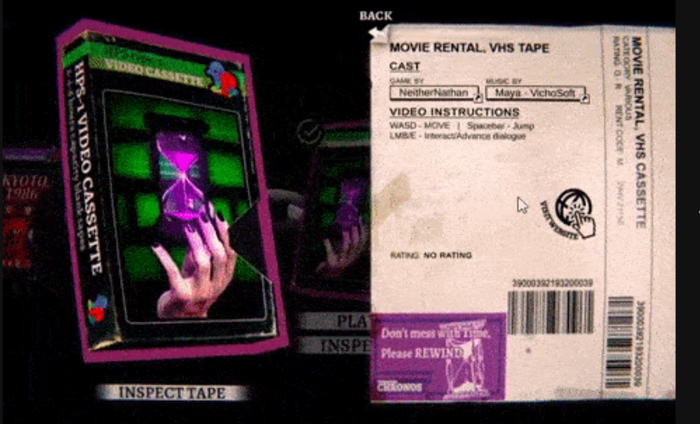

Pype: Colter Wehmeier helped a lot here. He developed a system that’s used in a lot of HPS1 collaborations that makes it trivial to load up any game program bundled into the launcher to be opened seamlessly. The only restriction on developers is that it had to be made for Windows, be controlled with mouse + WASD, and that the game had to end on a choice and quit by itself. Other than that, developers could use any engine they liked, and we ended up with quite a wide variety, from Unreal to RPG Maker games.

What benefits came out of this chaotic mixture of games and styles? How did you feel this sense of the unexpected and chaotic added to the horror experience as a whole?

Pype: I feel like it would be a misnomer to call CHAINGED a horror experience. There are a lot of horror themes, but only a few of the games are meant to be scary, I think. It ended up mostly as a bizarre, surrealistic narrative opera of sorts, if anything. I think the biggest reason is because the first game is very lore-heavy. That’s what I think is the magic of this project: that first game really decides what it’s going to be. If the first game was a top-down puzzle game, we probably would have ended up with a completely different thing.

Vladimere Lhore, developer of What Lies In Wait: The benefit is the same as most collections: if one falls flat, there are many more that could be very different and more your style. It casts a wider net on the audience.

Shadink, developer of Vessel: Well, you start off with an '80s-themed first-person thriller and end up with games that really surprised me. Like, I wasn't expecting some of these styles. At. All. And I'm so happy about that. Everyone put a part of their personality in here. This also adds to the main idea of the game: multiverses and branching timelines. To me, each game is like a new world created by its own God.

Davidrodmad, developer of Deja Void: While horror is not the sole focus of these games by a wide margin, as someone responsible for one of the spooky silent entries, I think the fact that players never know what to expect between humor, weird, drama, etc. does help to catch them by surprise every time.

Nikita Vychuzhanin, developer of Unbound: Every game created for the project is shaped by developers with all kinds of backgrounds, ideas, and inspirations. It never gets old as you jump from one short game to the other and you really can't be sure about what to expect next. In the end, CHAINGED is one of a kind when it comes to such variety in art presentation and genres in one playable experience, which I adore.

Kevin Hutchins, developer of If I Could Start Again: I've found that the games that give me the most enjoyment are ones with a healthy amount of novelty that persists throughout the experience, whether through new combinations of gameplay mechanics or changing up the type of gameplay entirely. CHAINGED has that in its most fundamental form. The story weaves its thread through dozens of different gameplay and story-telling styles. Many of them, including mine, aren't going for a traditional indie horror game style, but that variety gives the collection a variety of pacing that a sequence of five-minute-long pure horror experiences wouldn't.

What thoughts went into making a horror game that would focus on a single choice? What was the appeal?

Pype: I made one of the second games, and I think I was much more focused on trying to further the story from the first game but also trying to make it more gameplay-y compared to the first game. In retrospect, I don’t think that really worked. Making a game that ends on a choice is really cool though, because it’s interesting to try to come up with a choice that’s enticing enough. Most importantly, both options need to sound equally interesting and plot-inducing, as you don’t want to steer all players into just one branch.

Lhore: I love video games as a medium because your choices can affect outcomes. I’ve made several games focused around that on my lonesome, but the more choices you give, the more the scope balloons. I think spreading that scope among many devs is a fantastic solution, and allows choices to have weight. I would have liked it if more choices had been story-motivated, making players truly think about their next move, instead of Up or Down, desert or ocean, with no idea what to expect from either outcome.

Cuttlefresh, developer of Godhunter: For me, it was much less about the idea of choice as much as “Wow, I really loved the idea of CHAIN. Now we’re doing it again and expanding it.” I was really interested in seeing the whole thing play out, how this exercise in collaborative worldbuilding would work out. You’ve seen Choose-Your-Own-Adventure games (or even ‘experiences’ like Black Mirror’s Bandersnatch) but they’re always a bit monotonic, considering all the branches are made by the same team with the same style—the same goals set forth by the leadership.

With CHAINGED, Adam [Pype] really just said: “Here’s Nathan’s game, build off of it, spin off in directions expected and unexpected, and have fun doing it.” Since we’re doing this just as a passion project, we didn’t have to worry about appealing to everyone everywhere all the time.

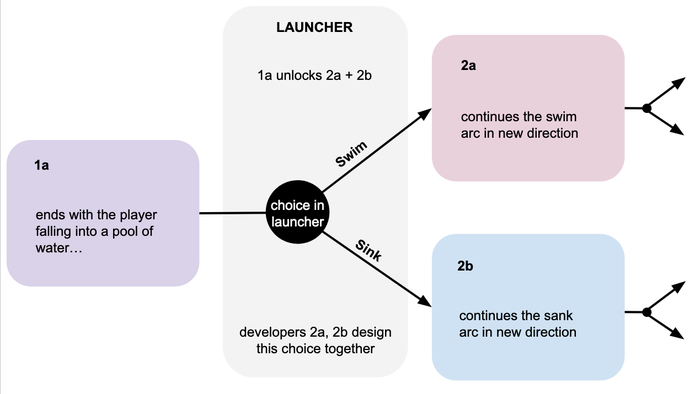

Colter, developer of Genesis: After releasing CHAIN, we explored a bunch of possible twists on the format that could make a stronger sequel. Branching paths were in the earliest discussions but seemed too complex if each submission had to implement that feature.

A pre-production diagram showing how we’d structure the choices.

Early work on the launcher showing the branches.

Later on, we had the idea of presenting choices in the launcher rather than in each game. This unlocked our ability to use choice as an organizing element in the sequel. Here are some of the ways we thought branching paths and choices improve from the first game:

1. We could develop the game faster by running in parallel rather than serial. While the first week only had one developer working, we got to 16 or so concurrent developers by the end. This meant we could have the game ready in a couple of months rather than taking a whole year like the first CHAIN, where only one dev would contribute at a time.

2. Addressing player dropoff by making later games more accessible. In the first CHAIN, we saw players start dropping off after the first couple of games, meaning later games in the sequence were getting ignored. With the branching structure of the sequel, we ensure player attention is better diffused among all the games.

3. Increasing player satisfaction and diversity with multiple endings. Multiple endings are somewhat trendy for games. For streamers who play the game, the order they explore the branches also means their play sessions are unique.

4. Increasing story cohesion. The first CHAIN was more like a game of Telephone where each developer could only see one preceding game in the sequence. The product is fascinating but quickly becomes incoherent, which generally confused players. By doing shorter branching paths and allowing each developer to see their preceding sequence, we ensure each branch is internally coherent, short, and sweet.

Lunar Finch, developer of Looptown: The first CHAIN had the problem of the narrative having too little cohesion for most players. The story was hard to follow because you were jumping between characters and places with no explanation. This time, having the player make meaningful choices has helped with forming this idea of an emergent narrative. In the case of my game, I tried to give the player choices that would result in clearly separate outcomes. It was very fun to see how the devs after me picked up those narrative threads and ran with them to wild conclusions.

Can you tell us a bit about the experience of designing a game based on another developer's title and choice as a jumping-off point? How did the previous game shape the experience you wanted to create? And can you give us specific examples of how it shaped your entry?

Pype: I think it’s really exciting to not know what you’re going to make until the day you get it. You only have a week to make the game as soon as it’s handed to you, so you have to be quick on your feet. It’s actually kind of nice as it’s a very specific prompt but you still have a lot of creative freedom. For my game, I knew I wanted to add some kind of core gameplay element, and when I chose to work on the Kyoto choice branch, it felt natural to make a mechanic with slicing a sword. It’s kind of interesting to make an experience without a beginning or end; it’s an unusually liberating task not having to do the hardest parts of making a game: starting and ending it.

Lhore: I had no clue what to expect going in. I could have just as easily been handed a story about space aliens, SCPs, or cryptids, but I was given the Antichrist and time travel. I remember being upset with the cards I’d been dealt at first. I felt the first game had created this well-defined box for us to play in. Stewing on it for a few hours though, I realized I was free to break this box and reassemble it. Instead of the story being about trying to save your daughter with the help of your friend Chronos, I stated up front, Lucy is dead and Chronos (probably) isn’t your friend.

Davidrodmad: Despite having worked on the previous CHAIN, the sheer amount of lore and material this time around really lent itself to creating building blocks on top of each other. I apologize to anyone who had to build upon our game, though, because we decided to make a weird broken time kerfuffle open to interpretation [laughs].

Cuttlefresh: I developed an ending game. All the previous games in my chain were set in a three-dimensional realm, and I work with RPG Maker, a 2D engine—one of the older ones, at that. Adapting the style was difficult in the week of development, but not impossible. If I had more time, I would’ve totally gone further, but one prerendered background was the best I could do at the time [laughs].

SPOILERS AHEAD

From a story standpoint I feel like me and Aare (my co-chainer) got the worse end of the stick since Catherine (the protagonist) made a lot of choices that were difficult to justify and hard to make a satisfying conclusion out of in our Chain. I had no vision of the game before I played the previous ones, but after I did, I knew that this Chain just had to have a more somber and introspective ending rather than a bombastic boss fight. Whereas in other Chains, Catherine faces off against GOD (or “The False Chained God” as I dubbed them) in a bonafide boss battle, in mine, there is no music, GOD doesn’t fight back, and it swiftly cuts to black after one shot fired. Originally, the Chain was supposed to end like that, but I cheated a little and decided to add a few lines post-development which implied Catherine is grateful for the chance to die like this.

Vychuzhanin: It's super inspiring to be given an unfinished story in the form of multiple games. After playing through them, I was instantly hit with *the vision* and got to work. The game that preceded mine ended with a choice between two equally deadly confrontations, so of course, I made a boss battle where you use an artifact that's strong enough to kill gods and throw it around like a rock and break stuff; playing with physics is always fun.

For my idea to work, I had to learn quite a lot of new nerdy, boring stuff, like how to make an object explode into pieces. There was a lot of improvising as I attempted to write cohesive dialogue between two characters for the first time as well. I really wanted to make something that stood out for variety's sake, to give the next games some room for how they want to approach the choices I presented them with. I believe I succeeded in that regard.

Shadink: It was a wonderful experience. I didn't have that much knowledge of game development, especially when I made Vessel, so it served as a cool learning tool as well. When Adam {Pype} sent me the Kyoto branch game and told me I had to make the choice to become the Antichrist, I got so pumped. I started thinking of all the ways you could fuck around while being the devil and I ended up with what I ended up with, which I'm pretty satisfied with! I picked up on some snarky humor and tried to expand it with my entry, which resulted in a surrealist comedy. I also noticed the biblical/mythical themes with Chronos and the Antichrist, and, since I'm a big fan of that, I tried to add as much as I could to it as well.

Hutchins: Signing up for the project, I was worried that I'd find myself at a loss for what to do, gameplay-wise, when it was my turn to develop something. To ameliorate that unease, I narrowed down two different gameplay styles that I thought I could pull off in a week while also fitting a variety of styles: a top-down obstacle-dodging game or a parkour-based first-person platformer. Once I played the games before me in my chain, however, inspiration struck. My narrative thread had explored sacrificing everything to save one person, and that claustrophobic experience felt perfect for a first-person dungeon crawler, a game type that I'd rarely played or made before.

What was your experience with trying the game as a whole once everyone's entries were in place? What did you feel when you could finally see the entire work as one story?

I’m going to admit something horrible here: I still haven’t played all the games. It really is a lot to get through and it’s hard to find the time for it. But I have done a couple runs already. It’s really incredible seeing it all together. Since my game was such an early one, you’re really surprised to find out what everyone made of it. The story immediately went in wild directions, and there are so many gems in there that each keep deconstructing it even more. We ended up adding a secret extra third branch to the game that unlocks after you play a couple of ending games. For this branch, we had each developer play every single game in the main branches and then do a kind of meta branch which tries to fit all of the stories together and give players a set of “true endings.”

Lhore: I really enjoyed playing each entry as they were being completed, but the process took so long that I got wrapped up running another collaboration, Madvent, and unfortunately haven’t had time to try out the Ghost Branch or all of Kyoto’s branch. But seeing all the games within my branch, I think the experiment of telling a cohesive story between so many devs was a success. Not every ending lands—I think only having a week to go from no clue to what you’ll be making to full development was rough on many devs, but some crescendo perfectly.

Cuttlefresh: Oh, it was brilliant. Surprisingly, a lot of recurring themes emerged—betrayal, self-sacrifice, love, hatred. I think a lot of the themes came packaged in with the very first game, so everyone was able to build off of that title and work with how the themes developed over the course of the chain.

Vychuzhanin: It felt good to finally see a completed project that's ready to be experienced by people outside the dev team. While playing the whole thing for myself, I kept track of all the similarities that existed between completely different story branches—there are quite a few, which is interesting considering the lack of communication between the developers.

Shadink: When I first played the whole thing, I was so satisfied. This big project we had all built felt so well put together, it was unreal. The thing that appeals to me the most is all the different ways things can go. Like, for example, with my choice, I'm sure any dev would've gone in a completely different direction, and that's probably what's most fascinating to me about CHAINGED: The possibilities and the expanding universe we each built with every game. It's a collage of ideas so different from each other, it makes it all work together in the end. On paper, you'd think it would be crazy and nothing would make any sense—probably even that some people's ideas would be similar and it wouldn't work in a satisfying way. But the beautiful thing is, there were so many brains from so many people working on this, that was pretty much impossible! Each person has a different creative process, and there are a million possibilities, even with the choice aspect.

Hutchins: Since I was one of the ending games, I made a conscious decision to avoid some ending types that I guessed would be frequent occurrences across other endings. When I finally was able to play all the games, I found that it was unnecessary. There's a huge variety of endings that you can discover across CHAINGED, and through the branching structure, they all end up being very different while still feeling like they're part of the same story.

Finch: I loved playing everyone’s versions of the story and seeing wildly different styles and genres. What’s most interesting to me is how several ideas kept appearing in different, unrelated branches of the game. I think everyone did a fantastic job in making the story detailed enough but leaving space for imagination to kick in and create a kind of meta-narrative connecting characters and places that the devs couldn’t have possibly known about. Of course, the ‘Ghost Branch’ then picks up these ideas and goes to wild places with them, but I won’t spoil that!

What effect do you hope these varied, surreal choices and experiences will have on players? What do you want them to take away from your collection of games?

Pype: It might sound a bit selfish, but I really think the main audience for this project was the developers themselves. For me, it was more about the journey of making it and experimenting with formats of development and collaboration. I just hope that players can see that as such; they are diving straight into an incredible treasure chest of wildly different creations by talented developers from all sorts of backgrounds. It’s not a very polished player-friendly experience in the end (although, we really tried our best to make it one), and I think that if you take that into consideration and view it with an open mind, you will really enjoy the work on display here and the beauty of slightly-uncoordinated organic storytelling and design.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)