Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the first installment of his comprehensive look into the current state of classic game preservation, John Andersen delves into strange tales of what happened to Atari's source code, the surprising rescue of Sonic Spinball, and much more.

[In the first installment of his comprehensive look into the current state of classic game preservation, John Andersen delves into strange tales of what happened to Atari's source code, the surprising rescue of Sonic Spinball, and much more.]

Trash cans, landfills, and incinerators. Erasure, deletion, and obsolescence. These words could describe what has happened to the various building blocks of the video game industry in countries around the world. These building blocks consist of video game source code, the actual computer hardware used to create a particular video game, level layout diagrams, character designs, production documents, marketing material, and more.

These are just some elements of game creation that are gone -- never to be seen again. These elements make up the home console, handheld, PC and arcade games we've played. The only remnant of a particular game may be its name, or its final published version, since the possibility exists that no other physical copy of its creation remains.

The passage of time, and even the inevitable passing of a game development team, diminishes the possibility of further elements being placed in safekeeping. Some of these building blocks are still kept in filing cabinets, closets, storage units, attics, basements, and garages. They may soon face the same landfill fate if they are not rescued.

As a community of video game developers, publishers, and players, we must begin asking ourselves some difficult but inevitable questions. Some believe there is no point in preserving a video game, arguing that games are short-term entertainment, while others disagree with this statement entirely, believing the industry is in a preservation crisis.

Where do the various assets of a single video game go once production and publishing is finished? How are these development materials handled after the game is finally published, and what should inevitably happen to them?

In a sense, video games go to sleep when they are powered off, but are reawakened once again when powered on. The existence of decaying technology, disorganization, and poor storage could in theory put a video game to sleep permanently -- never to be played again.

Troubling admissions have surfaced over the years concerning video game preservation. When questions concerning re-releases of certain game titles are brought up during interviews with developers, for example, these developers would reveal issues of game production material being lost or destroyed. Certain game titles could not see a re-release due to various issues. One story began to circulate of source code being lost altogether for a well-known RPG, preventing its re-release on a new console.

Research for this article began in January of 2009. A questionnaire on the subject of video game preservation was also sent to video game developers and publishers worldwide. The 2009-2010 period of research and questionnaire replies received from the game industry revealed a tragic reality -- a reality with anecdotes that have never been publicly revealed until now.

While many in the industry were enthusiastic to speak about the subject of game preservation, there were others that declined to comment or respond entirely. It was apparent that this was a subject matter that needed to be researched thoroughly, but approached with sensitivity. It is not the intention of this article to put a negative light on those that have neglected video game artifacts. The intention of this article is to also shed light on the state of video game preservation, and the attempts being made to preserve all aspects of video gaming for the future.

Some of the answers received for this article revealed a troubling reality, but the questionnaire allowed some industry professionals to explain how they went into a "rescue mode" of sorts, tracking down boxes of old software and hardware in the most unlikely locations to bring an older game back to a new audience via a console, handheld or online service.

The overall question asked was: how important is it for game developers and publishers to preserve their video games for future audiences?

This question was posed to video game developers and publishers in Europe, Japan, and North America for this article. 61 developers and publishers were contacted, and 14 responded.

Microsoft Game Studios, Nintendo of America, and Sony Computer Entertainment of America were the video game console manufacturers that responded.

The video game developers and publishers that responded were: Capcom, Digital Leisure, Gearbox Software, Intellivision Productions, Irem Software Engineering, Jaleco, Mitchell Corporation, Namco Bandai Games, Sega, Taito, and Throwback Entertainment. Many of these companies also produced coin-op arcade games and some were previously involved in game console manufacturing.

Their complete answers and statements will be presented in their entirety at the end of this article's final installment. A summarization of their comments revealed how they are taking steps to preserve their video gaming legacies, while others told stories of both loss and rescue.

Irem Software Engineering revealed that it has no intact source code from the 1980s, but still maintain ROMs for almost all of their games. Irem expressed concern that the hardware that helps maintain these ROMs will soon break down, fearing the parts and human engineering used to maintain them will soon be obsolete.

Taito revealed that some of the promotional materials associated with its games have been lost. It did reveal that it protects its game media based on internal policies and ISO standards. In certain cases Taito has transferred old console game data to reliable and secure media, while preserving hardware, ROMs and printed circuit boards for its arcade games. Taito considers the release of many of its older games on mobile platforms and console compilations such as "Taito Legends" to be an important form of protection.

Digital Leisure revealed that the original source code for Dragon's Lair and Mad Dog McCree was either lost or could not be accessed due to the media it was stored on. Digital Leisure would end up working with outside personnel and fans to re-create an authentic arcade version of these games for new platform re-releases. Digital Leisure also expressed their frustrations of being unable to acquire the rights to re-release older laserdisc games to new platforms, due to the fact that the original source material for certain laserdisc games no longer exists.

Throwback Entertainment disclosed its "logistical nightmare" of managing the acquisition of 280 different game titles they acquired from an auction of Acclaim Entertainment properties. Throwback's plan is to build a data center utilizing computers, networking systems and external drives acquired through eBay auctions to rescue source code. This source code had accumulated over a 25-year period at the now defunct Acclaim Entertainment offices formerly based in Glen Cove, New York.

Keith Robinson of Intellivision Productions recalls saving Intellivision source code. Mattel, its former corporate parent, had auctioned off 8-inch floppy disk drives that were essential in reading Intellivision game source code saved on floppy disks. Robinson would be forced to track down the company that had purchased the drives from Mattel at auction, and then call the drive manufacturer to obtain a correct jumper setting to get the drives functional once again.

The Intellivision game source code was finally transferred from floppy disk to a new storage format -- essentially rescued from obsolescence. A compilation of these games was recently released for the Nintendo DS in October of 2010, and can also be downloaded on the iPhone, iPad, and Microsoft's Game Room.

Console manufacturers Microsoft, Nintendo and Sony also shared their insights on game preservation.

Microsoft maintains special departments that are responsible for storing all gaming material in onsite and offsite locations. Microsoft currently has plans to transfer games made prior to the year 2000 from older media to new reliable storage platforms as part of its BCDR (Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery) program.

Nintendo highlighted its series of "Iwata Asks" features found on its website, and how original game design documents have inspired Nintendo designers throughout the years.

One "Iwata Asks" interview highlights how original NES design documents created in 1985 for The Legend of Zelda are continuously used as specification reference when Nintendo develops new installments in the Zelda series. Nintendo also highlighted the importance of its Wii Virtual Console service in preserving and reintroducing older game titles to new audiences.

Sony Computer Entertainment of America discussed the importance of the PlayStation Network and Home Arcade and how they're "extending the lifecycle" of older games. Sony disclosed that archiving externally developed titles "varied depending on contracts" as well as regions. Sony revealed the challenges that exist concerning the recovery of source code that requires specific obsolescent or unavailable hardware. According to Sony, BIOS expiration or revisions may pose significant problems with long-term storage of PC hardware and development tools.

Some companies that we approached for this article were understandably not willing to come forth to discuss the subject of video game preservation. Some cited company policy in discussing development matters, while some had no video game artifacts at all.

One such company contacted was an electronics manufacturer that once previously produced video game consoles and software. The company conducted a search for all available video game artifacts in its overseas corporate archive for the purpose of this article.

A stunning reply was given: no video game material such as hardware, software, or source code could be found in its official corporate archive. The company would eventually decline to participate in this article entirely, but did promise to further investigate why its historic video game legacy could not be found in its own internal archive.

Sadly, the tragic fact remains that a lot of video game artifacts were either dumped in trash bins, or abandoned altogether.

Stories of development teams arriving at their offices to find the front doors locked and their employer bankrupt are not at all uncommon. Depending on the organization of a developer or publisher, the management may not comprehend what is contained on storage media, or within filing cabinets, binders, and desk drawers when employees are let go. What does a video game company do with its game design material when its offices are closed or sold to another company?

There are unconfirmed reports of Japanese developers closing their North American divisions in the late nineties and leaving their old arcade games and office filing cabinets in storage units. Their corporate parent in Japan would eventually abandon these storage units.

One such company that made headlines for dumping game development material in the trash was Atari Corporation (not to be confused with the present-day Atari Incorporated, Atari Interactive, or Atari Europe SASU).

The following two incidents have nothing to do with old cartridges and hardware being buried in a desert landfill in 1983.

Atari Corporation would sell filing cabinets filled with game source code, production documents and marketing diagrams to bewildered buyers at its warehouses throughout 1984 and 1985. These rapid-fire office furniture clearance sales were done by the order of the Tramiel family, who had taken over Atari in 1984, laying off thousands of employees and selling off mountains of Atari office equipment to raise cash.

Patty Ansuini, vice-president of A.P. Construction in San Jose, California had heard that office equipment was being sold off at an Atari warehouse in nearby Santa Clara. According to a San Jose Mercury News article, Ansuini purchased a locked two-drawer filing cabinet for $125 from an Atari warehouse and was told she could keep its contents. What Ansuini didn't realize at the time of her purchase was that the filing cabinet was from an Atari game engineering office.

Ansuini brought the Atari filing cabinet back to the construction company office, and would hire a locksmith with a spare set of keys to get the cabinet open.

Once opened, Ansuini and her husband were shocked to discover cardboard file folders containing source code for 84 different games published on the Atari 2600, including Pac-Man, Ms. Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Centipede and Pole Position, as well as a word processing program. The filing cabinet even contained source code for Atari 2600 game prototypes that had not been published at the time. These prototypes included games based on the "Dukes of Hazard" TV series and the "Gremlins" motion picture.

Renowned game designer and former Atari programmer Chris Crawford remembers the contents of the cabinet Ansuini had acquired to this day. The reporter writing the San Jose Mercury News article in 1984 contacted Crawford to ask for help in identifying the cabinet contents.

Crawford recalls its exact location where Atari kept the cabinet for this article: The second floor of 1272 Borregas Avenue in Sunnyvale, California, then home of Atari Corporation VCS/2600 engineering. "I remember the secretarial station there right next to the Department Chairman's office in the corner; the filing cabinet was right behind her desk against the wall."

He clarifies what each element for one Atari 2600 game consisted of in the filing cabinet that Ansuini had purchased: "It would consist of three components for each game: the printed source code, amounting to a few dozen pages of striped computer paper; an 8-inch floppy disk containing the source and object code; and an EEPROM mounted on a PC board containing the final object code in a runnable format. Each programmer was required to deliver these to the VCS secretary as part of the final work on the game."

Ansuini made the prompt decision to return all of the game components to Atari Corporation. She made several phone calls to Atari headquarters and left messages with its head of security. She even tried getting a hold of then Atari president Sam Tramiel. No one returned her calls, but she was advised to call back.

Finally, the same San Jose Mercury News reporter that had contacted Crawford got a hold of James L. Copland, then VP of marketing at Atari Corporation. Copland sent over three Atari employees to Ansuini's construction company office to retrieve the Atari 2600 game source code contents for all 86 games. "It's a very sloppy way to unload furniture," Copland remarked to the reporter.

Atari Corporation's method of "unloading furniture" would continue at its warehouses and word quickly spread around the area. Cort Allen of Plesanton, California was another customer of the Atari warehouse sale. While Ansuini had purchased one filing cabinet filled with VCS/2600 source code, Allen purchased forty-four filing cabinets from Atari. The filing cabinets Allen purchased did not contain any Atari source code. What Allen found inside the cabinets would nonetheless turn out to be an astounding discovery.

Allen was in need of an integrated circuit tester for his business, Quest Consulting. He had heard from an Atari employee that the company was selling them at one of its warehouses located on Sycamore Drive in Milpitas, California. Allen made his way over to the Atari warehouse and would purchase a Megatest Q8000 Test System, used for testing PROMs (Programmable Read Only Memory). He recalls a chaotic scene from that day:

"I saw boxes of new, unsold games, many arcade game consoles, furniture, file cabinets, office equipment, supplies, and such. There were large 18-wheelers pulling into the loading docks hastily filled with contents from other Atari buildings in the area."

A few days later Allen would be informed of yet another sale where Atari was selling filing cabinets for $2.00 a piece. A friend of Allen's, who shared office space with him, purchased four of these cabinets and brought them into his office.

Allen looked inside the cabinets that his friend had purchased, discovered Atari documents, and decided to travel to the Atari warehouse where another chaotic scene was unfolding.

Allen didn't want the cabinets; instead he wanted what was inside the cabinets. It may have been business as usual at Atari, but as Allen recalls the scene, one could describe it as tragic.

Atari's history was once again being unloaded from offices by wheelbarrows and literally being thrown out into garbage dumpsters outside.

Allen asked an Atari employee on the warehouse loading dock if he could purchase the forty-four remaining wooden file cabinets. The Atari employee agreed with a $2.00 price for each cabinet, but innocently insisted that the contents of each cabinet be dumped in the trash. This would allow Allen to haul them home at a lighter weight. Allen was very careful to ask the Atari employee if he could keep the documents inside the cabinets. The bewildered Atari employee agreed and the sale was completed. Allen would haul 350 pounds of wooden Atari filing cabinets back to his home.

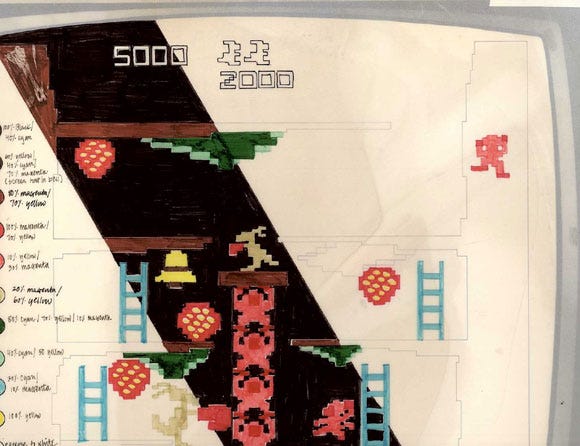

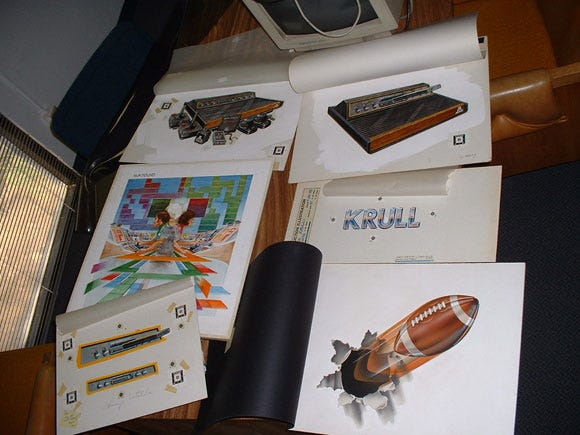

Inside the cabinets Allen discovered a treasure trove of watercolor frame design diagrams for various Atari published games including Namco's Pole Position and Dig Dug. Design diagrams for Atari's own in-house games were also found, including graphics and artwork for Atari Basketball and Golf.

Design graphics and artwork also appeared for a mysterious console called the "Kee Games Video Game System". Marketing tie-in materials with Sears department stores were uncovered. Carton and instruction manual proofs for the French, German, Spanish, and Italian language versions of select Atari games were also kept in the cabinets.

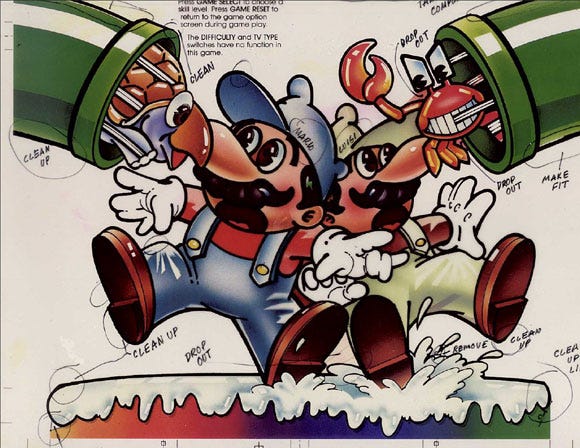

One of the more fascinating pieces found in one of the cabinets was Atari Corporation's own interpretation of games they had licensed from Nintendo at that time. Mario and Luigi character artwork intended for Atari's cartridge box and manual artwork was found with department notations.

In all, 2000 different pieces were contained within the cabinets from Atari Corporation's 1981-1983 history. In 2007 Sotheby's estimated that the documents were worth between $150,000 to $250,000. An auction was held in June of that year, and the contents were included in a sale titled "Fine Books and Manuscripts Including Americana". A detailed description of the contents can still be found on the Sotheby's website.

The items failed to sell at the Sotheby's auction in New York City, and Allen paid for them to be shipped back to his home. He still holds on to all contents of the cabinets, hoping to find a buyer and planning to put forth any proceeds of a sale towards the college loans burdening his two children.

"As I thought at the time I purchased them, the documentation I now have contains a snapshot into the history of Atari. It is a historical archive of many of the thought processes that went into the design of their games. You see the hand drawings the creative designer had as he drew up the characters. I bought the documents at the time to preserve this history, and because these were the "original" documents, only one set ever existed, and these were that set. I also felt that many of the original artwork might someday be valuable.

"Any one of these reasons was enough for me to purchase the cabinets and I have stored these documents for over 25 years now. I would like to see all the documents stay together. I would hope that someone will go through each of the 161 'packets' and produce a small history of the development and design of each Atari product."

That said, Allen is still trying to decide whether or not to break up the pieces from the documents or keep it all together as a collection.

"I enjoy looking through the documents and always enjoy what I see. However, I really am not the person who should be owning these; they belong to history. Yes, I am very willing to put these items up for sale. They need to be placed into some archive someplace. As with anything, the value is what someone feels it is worth. I often get offers from collectors for some of the original artwork."

On a side note, Allen's friend eventually threw away his four cabinets of Atari documents years later.

Collectors see a value in preserving video game development materials acquired from companies. Current game developers and publishers see a financial incentive in bringing these older games to compilation releases and online game subscription services. Developers of these releases look closer at contents including source code and can find technical value that saves them both time and money. In presenting older games utilizing emulation, the original game source code itself is important for a developer to examine the ins and outs of the original hardware it was designed for.

Jeff Vavasour, a well-known video game producer and programmer, has credits that include lead programmer on such console compilations as Midway Arcade Treasures and Atari Anthology. His contributions to programming can be played on countless video game compilations of classic titles developed by Digital Eclipse (now known as Backbone Entertainment).

Vavasour's own company, Code Mystics Inc., recently developed Atari Greatest Hits Volume 1 and Dragon's Lair for the Nintendo DS. Vavasour explains the importance of utilizing source code from an arcade game in which the hardware may have been designed to run only one game.

"Having the source code can be tremendously useful even in emulation when it comes to debugging. When something is not working the way it's supposed to, understanding the context of what the game is trying to do to the hardware is a big part of diagnosing the problem. Even poorly commented source code still has function names and variable names that can shed some light on what's going on.

"Beyond that, there's the need to reverse engineer certain state information. For example, in modern emulation packages, we need to know things about the game's current state such as whose turn it is, whether the game is over, etc. in order to change controller behavior in accordance with a modern console's controller standards.

"(e.g. an arcade game might've had people taking turns on a single controller, but the console has a separate controller per player; and player 1's controller shouldn't influence the game during player 2's turn.)

"We can figure out this stuff without source code, but it can be very tedious to locate the information that way. Having the source code shows us exactly how (and often precisely where) that information is stored in the arcade game's memory."

Scott Hawkins, founder of G1M2, is a developer that brought a number of Sega Dreamcast games to online game service GameTap utilizing its own in-house developed emulator.

Scott Hawkins, founder of G1M2, is a developer that brought a number of Sega Dreamcast games to online game service GameTap utilizing its own in-house developed emulator.

G1M2 also developed Data East Arcade Classics for the Wii, and the PS2 compilations of SNK Playmore's Art of Fighting Anthology and Fatal Fury Battle Archives. Hawkins explained how source code saved the day for a publisher when one classic game needed to have artwork removed in order for it to be re-released.

"One interesting example was when we were bringing an existing action sports game to a new platform. The game included a lot of in-game content featuring licensed brands and artwork. Unfortunately, the licenses had expired, so the banners, logos, and other previously licensed items needed to be removed or swapped out.

"Luckily for that project, we had access to source code and it was relatively easy to replace the licensed content with generic non-licensed items. If we did not have access to source code, the publisher would have had to pay to re-license the content so that it could still be in the game, we would have had to hack the items out of the game without access to source code, or the game would not have been able to be re-released for a new opportunity.

"Swapping out music or certain art items can be easy, but changing character models or other major game features can become a showstopper without access to source code," says Hawkins.

Having no source code almost proved to be a showstopper for Hawkins when a company he previously co-founded known as CodeFire was developing Sega Smash Pack for the Game Boy Advance in 2001. Sega Smash Pack was a compilation that contained Golden Axe, Ecco The Dolphin, and Sonic Spinball, released in 2002.

Hawkins and his team had little or no access to source code for any of the games during its 2001 development timeframe. They were forced to recreate Golden Axe from scratch with a utility that compiled all of the in-game art assets. The source code for Ecco the Dolphin was located at an external developer that had adequately backed up the project. Hawkins retells a story about locating the source code for Sonic Spinball, which ended up being found in an unlikely location:

"Sonic Spinball had been developed by an internal team at Sega called Sega Technical Institute (STI), but the computers that had the backed up source code were no longer at the office and no one appeared to have a copy of the archive. I started asking people within the company, people that had worked on the project, but were no longer with the company, and other people that had been in that department whether or not they had worked on the game.

"The lead designer of Sonic Spinball replied to me that he had a copy of the original design document for the game. I told him that was cool, but it would not help me with porting the game to a new platform.

About two weeks later, I received a very interesting call. The former director of technology for the group called me up and said, 'I have good news, bad news, and strange news. The strange news is that you asked me a couple of weeks ago if I had a copy of the source code for Sonic Spinball, and while cleaning out my garage this weekend, I came across a box labeled 'Sonic Spinball'. The good news is that it may have the source code in it. The bad news is that the disc is a magneto-optical disc and I have no way of confirming the exact contents of the disc.'

"I sent our project coordinator over to pick up the magneto-optical disc, we gave it to our creative services group (which still had a magneto-optical drive at the time), and luckily for us -- it had the source code we were looking for! This story had a happy ending -- as the source code worked great for us and we shipped Sega Smash Pack for the GBA with all three games included in the product (and we did not have to recreate Sonic Spinball from scratch)."

Hawkins would go on to deliver the original Sonic Spinball source code from the magnetic optic disc to Sega, (along with a backup of the source code and assets for the GBA version) after the project was completed.

Sega of America revealed in a corporate blog entry that it does maintain a storage room with game archive cabinets in its San Francisco headquarters. Blog readers were quick to point out that upon examination of the game archive images posted on the Sega blog, many unreleased Dreamcast titles were found including Dee Dee Planet, Far Nation, Propeller Arena, and Real Race.

Many development and publishing contracts have a milestone in which all materials are backed up. The Sonic Spinball story brings up one important but simple action that developers and publishers could act on to save source code that was once thought to be lost.

That simple action consists of developers and publishers re-establishing contact with one another to recover source code, and all project assets for video game titles that were published years ago. For example, does a publisher in the United States, Europe, or even Brazil have source code to a game that was lost by its original developers?

This has been a common occurrence within the motion picture industry when original film negatives and sound elements are remastered for DVD, Blu-ray, or TV broadcast. Film elements that were once thought to be lost have been rediscovered in overseas vaults once utilized for foreign distribution.

A present-day check-in between video game developer, publisher, and production team members could uncover material that could be returned to its copyright owner, thus ensuring its security for future use.

Hawkins and Vavasour also emphasized that the emulators used to bring older games to new consoles and online game subscription services is source code itself, and should also be backed up.

"We back up and preserve our source code and project elements -- as it makes it easier for us to bring out technology to other platforms. Depending on the target platform, we may re-write an emulator completely from scratch, but it is much easier to port our existing emulation technology instead of re-inventing the wheel.

"It can be helpful to take the lessons you have learned from a project and start from a new beginning -- but either way, it is important to save the source code and keep it safe for future opportunities," says Hawkins.

Vavasour mentions his own emulators adding, "The emulator is source code too, and is subject to the same digital obsolescence as the original game's source code. You have to keep copying to newer media and adapting the code to new target machines as they arise.

"My first emulators were designed to run in MS-DOS 4.x, written in the Tandy Deskmate editor, assembled using Microsoft's Macro Assembler 5.11, and stored on 5 1/4" floppies. Basically, it's useless dead code now that would either have to be ported, or the MS-DOS 4.x environment itself would have to be emulated just to get the emulator working."

Maintaining original coin-operated arcade games, console hardware and software is essential for some developers to pinpoint the speed and overall authenticity of a game when re-releasing it on a new console compilation or online game subscription service.

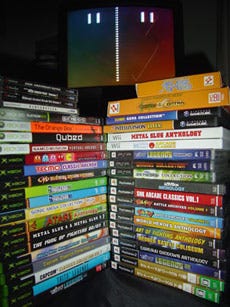

Terminal Reality is a developer responsible for re-releasing classic SNK games through such compilations as Metal Slug Anthology and SNK Arcade Classics for the Nintendo Wii, Sony PlayStation 2, and PSP. Although the company had access to source code for most of the SNK games, Mark Randel, CEO and lead technologist of Terminal Reality, explained that the developers tracked down the originals to authenticate what they were releasing for all three consoles.

"When we were searching for old SNK ROM cartridges, we would constantly monitor eBay for a game we were working on to pop up. We had some very good luck during the production of Metal Slug as most of the games popped up for auction before release -- although we couldn't actually afford an original copy of Metal Slug 1."

Terminal Reality found as many old ROM cartridges as possible and bought actual arcade cabinets to put them in.

"After many late-night play sessions, you'll just know when your version isn't close enough to the original. We broke many joysticks doing this. Because we're talking about classic and adored games, much of the QA staff were extremely hardcore, old school players. They know pixel glitch and slowdown that just has to be in there to accomplish authenticity!" Randel says.

Authenticity also means having access to materials that helped bring games to market, from print and TV advertisements, down to the logo of the game title. These materials not only can be utilized to help a developer acquaint themselves with what the original developer and publisher had intended for the game, but can help inspire updated concepts for a re-release. For players they have been an added incentive to playing a classic video game as Hawkins explains:

"Classic production assets are very valuable -- as they can be used for in-game rewards, marketing promotions, and other UI elements. When we did Data East Arcade Classics for Wii, we allowed gamers to unlock classic arcade artwork, flyers, bezels, and marquees. We felt this was a nice way to reward the players for completing certain goals and it also helped to add extra replay value."

The question that remains is where do all of the elements that make up a game be stored securely and kept safe?

Natural disasters and elements have played a role in destroying video game history. An examination of this history does reveal at least one major video game developer, Konami, did lose valuable development material in a major earthquake.

Part Two of Where Games Go To Sleep examines what happened to Konami and its game development divisions when it was caught in the midst of one of the world's worst natural disasters. Video game museums worldwide also reveal what steps they are taking in saving important video game artifacts from garbage landfills and the threat of data obsolescence.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like