What's your style as a creative leader?

This three-part series will cover three aspects of creative leadership, i.e. that messy head-space where lead designer meets producer, starting with creative direction as internal pitching.

Written by Tanya X. Short, the Captain of Kitfox Games, a small independent games studio in Montreal currently working on Boyfriend Dungeon and BadCupid.

This is the 2nd part of a series. Click here to read part 1, introducing the idea of creative management practice as learning how to pitch to your team.

“How can I improve as a creative director?”

I used to hate the idea of practicing creative direction or management, because whenever I started wondering how I could improve, it seemed like I was threading a needle between two bad places: micromanagement and lack of direction.

And I do think it’s helpful to get a general, high-level idea of your current effectiveness, by asking questions like:

How many other humans understand why I’m making this?

Does my team seem excited and challenged?

Is my team’s personal expertise showcased in the project?

Does every team member understand and support the project goal’s?

But the binary thinking of “good” versus “bad” direction is not particularly helpful, and can actually create a lot of insecurity and neuroticism.

Style Strengths

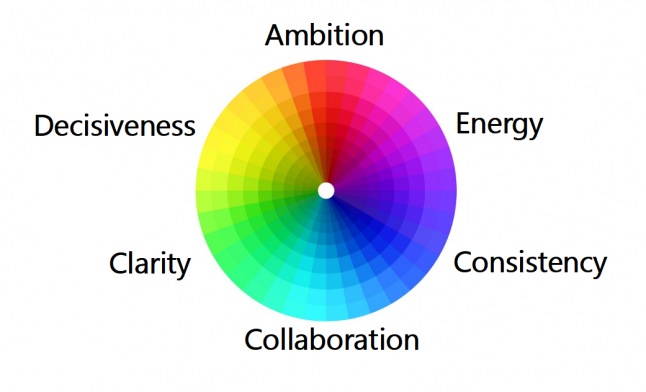

We’re all more complex than a simple binary, and with a little bit of introspection, we can dive deeper into the details of what makes our personal creative direction more or less effective, so a more representative spectrum of analysis would look more like this:

With each Kitfox project, I’ve learned a bit more about creative leadership, and it’s shown in improved results for each game, with a progressively tighter, more focused and interesting player experience.

From Shattered Planet, I learned the importance of answering why and for whom a game needed to exist. (I.e. for this project, I had no idea) It was called “a very good roguelike” in The New Yorker, which I’m proud of, but left us wanting to make a game with more purpose.

From Moon Hunters, I learned the importance of strategic design delegation, and that my personal values could resonate with the team & the game audience. It won many awards, was on the cover of at least 1 magazine, and continues to sell well, but with a core team shift and multiple project management mistakes, my main pride in the project continues to be that underneath it all, it reflects things I believe and continue to be fascinated by.

From The Shrouded Isle, well, I wasn’t the creative director, but from Jongwoo and Erica, I experienced first-hand the power of a truly distinctive art style and boldly ludo-narrative-congruent play experience. It was our first Eurogamer “Recommended” review, with a two-page spread in Edgemagazine.

And of course I continue to pour my heart and mind into Boyfriend Dungeon, which is our highest-potential game yet, but I’m not going to jinx it by getting ahead of myself. Ahem.

My point is that over each game, I discovered an aspect of myself that I could work on, in order to improve the results (or, the likely results) from my team.

Self-Improvement

Since our ultimate goal is to make better, more efficient, (etc) games, it’s tempting to focus on goals like:

higher game quality

better team work ethic

stronger innovation

better-defined scope

But ultimately, those things aren’t in your direct control. As a leader, your primary goal is to create a stronger team, who creates better results, and all you really have control over is yourself.

So, after thinking long and hard about what I look up to in leaders I’ve had in the past, these are the top 6 style strengths I try to work on as a creative leader, with varying levels of success:

Brief explanation of my thinking for each:

Brief explanation of my thinking for each:

Ambition: the drive and vision to demand the appropriate output from each team member. It can be tempting to scold your team over the quality of the project, when really it’s possible you should scold yourself over not having the appropriate Ambition. With each game Kitfox makes, I try to raise our collective level of ambition for the project, as art and as a product.

Energy: a positive attitude that can make work as a team exciting, enjoyable, and optimistic. It can be tempting to worry about your team’s work ethic, but you can’t control that — you CAN control what emotional impact you have on them, when you are nearby.

Consistency: self-control and discipline in communication over time, which wastes less of the team’s time changing directions. Obviously direction should solidify and cohere over time, but ideally it wouldn’t wander or backtrack too often. It’s more productive to work on my consistency, rather than try to increase my level of control.

Collaboration: an ability to work well with the different team personalities, and together create something we couldn’t alone. It’s something I can work on within myself, rather than feel helpless when there’s a lack of creativity or fresh ideas coming from the team.

Clarity: communicating with utmost accuracy and efficacy, at its extreme as if the team could read my mind.

Decisiveness: a tool that supports higher clarity and energy, since team members don’t have to be blocked by me. In an ideal world, I wouldn’t agonize for days over something unless that time was truly warranted.

Example self-analysis: By my nature, I’m fairly high in energy and decisiveness, but those two naturally undermine my consistency and clarity sometimes, since I get so excited about something I change direction and disrupt everything on a whim. And it can be difficult to be extremely visionary-level ambitious when really, it’s more comfortable to be supportive and let people (to some degree) define their own “best”. I’m honestly often too tempted by novelty, so I often need to buckle down with discipline to see things through to the end.

“[…] rather than worrying about “too much” vs. “not enough” creative direction, you should examine the kind of direction you’re giving, and why.”

Anyway, feel free to make up your own spectrum with your own style strengths. Maybe these don’t speak to you, or you just want to strive for 4, or you have 10 you admire. According to some studies on the topic, the core 6 skills a manager should develop are self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skill, but I felt those were too vague to me, and also didn’t capture the creative side of my job.

The point is to have a rubric by which to examine your decisions and behaviours, to improve yourself towards your own ideal creative leader. Go for it — be honest about how you want to grow!

The point is that rather than worrying about “too much” vs. “not enough” creative direction, you should examine the kind of direction you’re giving, and why. By knowing your own tendencies, strengths, and temptations, you can better-assess where there might be gaps in how you lead your team.

Styles and Style-Switching

As found in studies of management, effective leaders change between different styles, depending on the situation and what the team needs. Sometimes you need to be more ambitious; sometimes you need to be more collaborative.

You can read a full analysis by the Harvard Business Review here of 6 major style types (coercive, authoritative, affiliative, democratic, pacesetting, and coaching), which comes with a description of each one’s strengths and weaknesses.

These are mostly defined by the types of approach taken —for example, an ‘authoritative’ leader “states the overall goal but gives people the freedom to choose their own means”, while a ‘pacesetting’ leader “sets high performance standards and exemplifies them”. (Surprise! Although it sounds appealing, pacesetting leadership styles end up being almost as bad for culture as coercive leadership styles. Definitely read up on it if you’re curious.)

However, I find this approach less helpful because it has too many variables. If every style is potentially useful, and each one has its own emotional intelligence challenges when practiced, that ends up being 60+ different reasons (or excuses) why my approach failed or succeeded in this or that context, which is a bit overwhelming. But hey maybe it’ll help you, and I find it an interesting thought-experiment to try every few months, so I thought I’d mention it.

Questions to Ask

It’s helpful to come up with questions you can ask yourself about each style strength, which then help you assess your specific behaviours over the past weeks or months or years. For these 6 I’ve chosen, for example:

Ambition: Do I ask too much (or too little) of my team’s skills and experience? Is my feedback style helping the team feel challenged and give a clear route to improve? Is the work I am giving my team making the most of their talents? Is the team learning from this project?

Energy: How am I improving the positive energy of the team? What have I done to make our team a more pleasant, productive work experience? What can I do to energize each team member?

Consistency: How much have I been willing to stick to a difficult direction, even when it wasn’t easy or obvious? Conversely, how often have I deviated from my previously stated direction without good justification? How well have I followed my own direction?

Collaboration: Do I understand and empower each of their individual strengths and talents? Have I allowed room for others to take ownership of the game where they can? Do I facilitate team members working together directly without my involvement? Do I truly welcome feedback from every team member, and provide enough avenues and opportunities to receive it in a sincere way?

Clarity: How well do I communicate the project goals, especially for team members with different preferred learning styles or mediums? How well do I understand my own direction and goals, and can express them to others? How well do I prevent or clarify misunderstandings and facilitate the team to self-identify murky or vague areas in my direction?

Decisiveness: Is there any way I can make my decisions faster without endangering the company or project? Do I spend time on decisions proportionate to their ultimate importance, or do I let fear, insecurity, or ego stop me from making decisions as quickly as I can? Do I truly value my team-mates’ time and efficiency, and if so, how well do I communicate that with my behaviour?

Each strength has its own challenge as a creative leader, and any can potentially be dangerous if used in excess, without being moderated by common sense, and/or the other style strengths.

Summary

We all want to be better, but we all have different weaknesses to work on. The important thing is to focus on tangible aspects of your leadership style that can better guide your team, rather than worry about “micro-management” or “lack of direction” (which are problems, but too high-level, kind of like if a doctor tried to diagnose a patient with “something hurts” as the only reported symptom).

In the 3rd and final part of this article series, I’ll give some advice on giving compelling directions (if you’re impatient, just go read Leading Teams by J. Richard Hackman, which will be my primary source), and share a few tips on how to work on each of the 6 style strengths.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)