Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Many games are set in warzones -- but what do the developers who live through violence produce? In this feature, Gamasutra speaks to developers in regions that are tumultuous to find out what they want to create and why.

What's it like to create games in a warzone? We're talking about the same kind of environments mimicked in our most violent shooters and open-world adventures, video games that often ignore the real people traumatized by the bloodshed, and the near-constant state of anxiety their lives have become?

Gamasutra talked with several developers in countries torn by war or trying to rebuild after a revolution, seeking to learn about the struggles of trying to make games while there's an insurrection mounting and the cracking sound of gunfire outside.

We wanted to know how the violence around them -- which for some has lasted for decades now -- has affected their local game development community, how they make games, and what kind of games they want to create.

For Syria, the Arab Spring that transformed the Middle East and North Africa last year has stretched into several bloody seasons. The government's attempts to quell an ongoing uprising have left thousands dead, and there's no end to the violence yet in sight.

Following news coming out of Syria, where atrocities by its military and security forces raise the death toll every week, it's difficult to keep track of the horrors: protestors killed on the streets by snipers and tanks, neighborhoods shelled by artillery fire, ceasefire promises ignored, whole families executed, and massacre after massacre after massacre.

Game developer Radwan Kasmiya recently closed his game studio AfkarMedia in the country's capital Damascus, where the fighting is currently at its fiercest as rebels attempt to liberate the city. He's now devoting his time to another company he helped co-found, Falafel Games in Hong Kong, where he's still producing titles for Middle Eastern players.

He started his move to China in early 2011 as protests began to break out across the region, seeing opportunities in Asia and sensing a building tension in his own country. "I knew that something was going to happen," says the developer. "The problem is that my market is in the Middle East, so I have to be near my market, my audience, the gamers."

Syria's troubles gradually made operating a game company there seem impossible -- global sanctions and the country's instability scared away investors, and security forces targeted AfkarMedia, raiding the Damascus studio and arresting one of its workers. Kasmiya ended up having to close the office after a government order to evacuate the area.

Syria's army shelling buildings, battling rebels in Damascus

His team started to work from home, which was fine for a while because their neighborhoods were relatively safe. The escalating conflict and other issues, like the government cutting off online access, became too much, though: "Our internet connections became unstable. We couldn't speak or connect to each other. So, it went from bad to worse."

So Kasmiya made the decision to shut down the studio and focus on Falafel Games. He spent a year and a half traveling back and forth between Hong Kong and Syria for business, but the intensifying violence, which the Red Cross now says has spiraled into an all-out civil war, eventually made visiting there too risky.

Kasmiya says other developers have also fled Syria to escape the conflict, finding work at CG companies in less tumultuous Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, if not in Europe and the United States. It's unclear if they'll return once the country is at peace again.

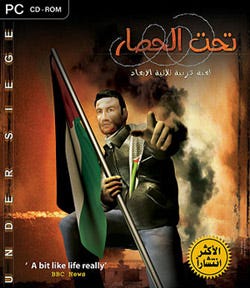

Despite the distance he's put between himself and his old home, Kasmiya is hesitant to put out a game commenting on the chaos he's left behind. It's surprising, as he's never been accused of shying away from controversial regional topics for his games before -- his most well-known works are Under Ash and Under Siege, locally popular first-person shooters in which players take on the role of Palestinians fighting against Israeli soldiers.

Despite the distance he's put between himself and his old home, Kasmiya is hesitant to put out a game commenting on the chaos he's left behind. It's surprising, as he's never been accused of shying away from controversial regional topics for his games before -- his most well-known works are Under Ash and Under Siege, locally popular first-person shooters in which players take on the role of Palestinians fighting against Israeli soldiers.

Half-Palestinian and half-Syrian, Kasmiya has always sought to release games that serve as "cultural social tools" (though others prefer to call his works propaganda). He has an idea, a prototype, for a game about the events that have wracked his country and the Middle East, but he isn't willing to do anything with it yet.

"I don't think it's safe," says the developer. "Because I'm still trying to go back and forth to Syria, and I still have family there. I'm not going to jeopardize anything. ... I can't practice my freedom of making art or releasing my own creations. I always have to consider these other things. We are not free. I am not free."

The fighting in Syria has spilled over the country's borders, sending errant mortar fire and sectarian clashes into its neighbor Lebanon in recent months, along with tens of thousands of refugees.

Skirmishes in Lebanon between militant supporters and opponents of the Syrian regime have left dozens dead and hundreds wounded.

While the country's capital is far from the Syrian border, the violence has managed to seep past Northern Lebanon and into Beirut. That's where six-month-old start-up Game Cooks is trying to establish itself as a mobile game studio creating titles for both Middle Eastern and international audiences.

But it's hard for the team to concentrate on that goal at times due to the conflict. "You're always distracted by the news," says Game Cooks head Lebnan Nader. "If you hear a bomb going off nearby, you want to hear about it, you want to see the news. You just waste time away from what you really need to be doing, developing a game."

He's speaking from experience -- Nader and his co-workers have been unable to even leave their office in the past after hearing gunfire and grenades going off nearby. "If that's going on, you're not able to work anymore. People aren't trying to kidnap us, but if it happens on the next street, it gives you a bad vibe, and it kind of cuts you off of your creativity and development."

Sectarian fighting in Lebanon a couple of months ago

Lebanon and its ruling political party Hezbollah (declared a terrorist group by the U.S.) are no stranger to violence. Even before the Arab Spring, Lebanon spent the past decade trading rocket fire for airstrikes and an invasion from Israel, wresting itself from a Syrian occupation, and almost falling into another civil war in 2007.

"You had ups and downs," explains Nader. "Now we're down, I guess. You had summers where you thought about nothing except going to nightclubs, and you had summers where you had to stay home because there's a war outside."

He says that instability has had a damaging effect on the culture and Lebanon's progress as a modern nation: "A lot of the youth here in the country, they follow politics and they follow those ideas. Very, very few concentrate actually on technology. So, this affects overall the passion for developing anything related to tech."

Nader contrasts that environment with San Francisco, where there's a rich tech-focused community. "If you need anything, they can help you. If you want to share ideas, they're there for you. Whereas if you're in Beirut, it doesn't exist. Nobody talks about [technology], or very, very few people. You don't feel like you'll get help with just anything you need."

Lebanon's underdeveloped infrastructure is unavoidable; slow internet connections are a constant annoyance for Game Cooks -- Nader recounts how when the company first opened, his team would spend more than a day trying to download software development kits and libraries for iPhone and Android, and their connections often cut off.

Game Cooks has been able to overcome all those challenges, though, and has just put out its first game, Run for Peace. It's an arcade-stye iPhone and iPad running game, in which players sprint across Middle Eastern countries (e.g. Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Iran, etc.) to spread a message of peace while avoiding missiles, radioactive boxes, and other hazards.

Game Cooks' Run for Peace

The studio is cautious to avoid referencing anything related to Hezbollah or specific politics or religions in the game -- making the wrong references upsets different groups. "We really do not want to draw the attention of [extremists], believe me," says Nader. "We try our best to remain as low profile as possible. ... We want to focus on the fun part of the game and on the good cause of the game."

He continues, "Everybody on the team just wanted to develop something for peace. We were pushing to develop something for peace because this is what we need to do. If all the Arabic players are somehow playing this game and having fun, and without noticing they are playing this game for peace, then this is a good added value."

On the other side of the world, El Salvador is another country where violence on the streets has become common, and hundreds are killed every month.

While most of the casualties are the by-products of turf wars between rival gangs, instead of the military or sectarian conflicts devastating the Middle East, the results, seen in the busy morgues, are the same.

The small Latin American country has one of the highest murder rates in the world, but it's the savagery of those killings that has shocked many: victims tortured and raped before they're executed, corpses found mutilated and sometimes beheaded.

Not too long ago, one gang intercepted a pair of city buses, setting fire to one and killing around a dozen trapped inside, just to send a message to authorities cracking down on crime.

It's a drastically different environment compared to North America or Europe, says Sergio Rosa, creative director for The Domaginarium and one of the few game developers in El Salvador.

He points out that there's no game development culture, either in El Salvador or its neighboring, equally violent countries Honduras and Guatemala (the three make up what some call a "triangle of death" in the region).

Screenshot from an early build of The Domaginarium's Enola

There are few opportunities for indie developers to find local support and develop their craft as a result. It's not like, say, Sweden, with its rich demoscene history and budding game industry -- it's improbable that El Salvador will produce anything like Minecraft anytime soon.

And even if it did, someone like Minecraft creator Markus "Notch" Persson would presumably not want to stay in the country for long. Kidnappings have been on the decline in El Salvador in recent years, but the Swedish game maker would still be an obvious abduction target and would likely be held for a large ransom.

"He's very open about [Minecraft's sales]," notes Rosa. "Here you have to keep a low profile. You can't let everyone know you are one of the richest people in the country, unless you have a lot of security guards." He advises against talking to the media about any big successes that could attract the attention of local criminals.

Rosa also doesn't think creating a game about the gang violence that's become so prevalent in El Salvador would be wise, either. "I wouldn't want to mess with that. The gangs can be very sensitive," he says. Indeed, it was just three years ago when photojournalist and filmmaker Christian Poveda was gunned down after releasing La Vida Loca, a documentary about the country's gangs.

Trailer for La Vida Loca (NSFW: graphic video, partial nudity, language)

However, Rosa is making a game that's definitely born from the violence he's seen in El Salvador, a horror/adventure title that's more about reprehending the barbarism that people are capable of, instead of glorifying or rewarding it. His studio's game, Enola, has players tracking a serial killer that tortures his victims.

"[With some of the violence here], everyone in this country goes, 'It takes a really sick person to do that,'" comments the developer. "When people are found inside plastic bags without their heads or limbs, everyone says, 'It takes a really sick person because it wasn't enough to kill someone. The killer wanted to show us how brutal he was.'

"So I came up with this idea of having brutal games, but not in the sense of you are the tough guy beating up everyone, rather you are the innocent guy seeing other guys doing all this bad stuff. From that change of perspective gameplay-wise, the way you react to the world will hopefully be different."

Rosa adds that having a human serve as the antagonist in the game, rather than undead creatures or aliens, is crucial for creating the terrifying experience he has in mind. "People can do very bad things, and you can see that in many places, including El Salvador," he says. "That's more scary, at least to me, than having a 10-foot monster chasing you."

A year and a half has past since Egyptians took to the streets to protest and oust long-ruling president Hosni Mubarak and his government. Though the country's Arab Spring wasn't nearly as bloody as Syria's or Libya's, hundreds of demonstrators were killed during its revolution, mostly in violent clashes with the police and pro-Mubarak forces.

Based in Egypt's second largest city Alexandria, developer Nezal Entertainment was right in the thick of those protests; many of its employees even joined the marches in Cairo's Tahrir Square that helped end Mubarak's 30-year-reign and bring significant reforms to the country's government.

Now that Egypt has a newly elected head of state, Nezal's Mohamed Sanad is confident that the country is entering a new era, and is excited about the growing game industry in the region.

He says several online/social game start-ups have opened since the revolution, and entrepreneurs haven't been afraid to back Egyptian tech companies. "We hope for a new future, so they've decided to invest here."

Sanad also says the studio has been eager to create a game about the events that changed its nation -- the team felt that making a game about anything else didn't seem right.

"The whole country had nothing to talk about but the revolution, what happened to the president, what is going on with the politics, and so on," he explains. "We saw it wasn't appropriate to start just a funny game or something like that right now. Maybe the market is not ready for that kind of thing."

Nezal's Crowds: Voices of Tahrir

So the company released Crowds: Voices of Tahrir, a rhythm title for social platforms. The game has players pushing a group of marching Egyptian citizens toward Tahrir Square as they wave flags and yell out the same chants that were heard during the actual protests. Along the way, they're met by obstacles like tear gas and baton-swinging security forces.

Many other game makers have had similar ideas -- just a couple of weeks ago, hundreds of developers gathered in Cairo, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia to create over 40 projects around the theme of freedom at a region-wide game jam.

Because Nezal is living in a post-revolutionary state, Sanad says there isn't any fear of reprisal over the critical content in the studio's game -- a liberty not yet enjoyed by developers in Middle Eastern countries still in flux.

"We have a new government, a new president," says the developer. "The old regime is not here anymore. We do not have those concerns like we had [before]. Things are better now. We have more freedom, so it's okay."

That's not to say everything is perfect in Egypt now, as the country is still mired in a power struggle between the military and dominant political parties. For Sanad, who remembers the rampant corruption, police brutality, and censorship under Mubarak's decades-long rule, though, there's a lot to be optimistic about. "It can't be worse [than] before. Never."

There's also hope in the voices of the other game developers profiled here, despite the wars -- waged by gangs or armies -- playing out in their neighborhoods instead of just on their computer screens.

In El Salvador, where gang violence has been a fixture for two decades now, Sergio Rosa observes that the murder rate has fallen dramatically after a truce declared between the country's biggest gangs earlier this year. He's unsure how long that ceasefire will last, but even if it the violence ramps up again, he emphasizes that there's more to El Salvador than just its crime.

"I don't want people to think this is a horrible place, that I hate this place," says Rosa, before calling attention to the country's beautiful attractions, like its beaches and Mayan ruins. "We have good things, we have bad things, just like every other country in the world."

And though the fighting in Syria is now at its worst in months, Radwan Kasmiya anticipates that the country and others in the Middle East North Africa region could see a change similar to Egypt's.

Egyptians in Tahrir Square waving Syria's flag in solidarity (photo by Al Hussainy Mohamed)

"We've been living under several types of dictatorships and lack of free speech," says Kasmiya. "I think the new generations -- and I am glad to consider myself among them -- we are saying enough is enough. We are trying to build our future, our own future."

He continues, "With the Syrian revolution, now it's violent and bloody and you can see all this tragedy, but if the cost of this will create a new, free country, not only Syria, free countries in the Middle East, I think that's a price we have to pay."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like