Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Throw Nothing Away: Lessons from the Making of Steel Rats

Tate Multimedia's Michal Azarewicz writes about letting your experiences drive your design, iterating on your own passions and talents, and leaving no idea behind in the new motorbike combat racer Steel Rats.

If you’ve never seen development of a game through to completion before, I think it may be easy to look at the great games that get released and assume they’re born with a clear direction in mind. Even the way we talk about games after they launch can fall into this trap: “It’s Metroid + Dark Souls + Clash Royale + The Sims -- an instant recipe for success.”

Plenty of games can be described with such a formula, and I don’t doubt that some of them actually start with that formula already in mind. But for most of us, it can be risky to try to develop with an end result in mind too far out.

We’ve always tried to do the opposite at Tate Multimedia. From inception to production to launch, our aim is typically to create a recipe for how we want a project to start, not how we want it to finish. From the outset, we focus on the things we want to accomplish, making sure not to abandon those goals, ideas, or the work we’ve already put in as a team along the way. This is a philosophy we continued in making our newest game, the “retro-dieselpunk + motorbike combat + action platformer” Steel Rats, and I’d like to share with you a few ways it influenced our development process.

Discovering Your Direction

As a team, we’ve always been drawn to the kind of fun gameplay that can emerge from realistic in-game physics systems, like in our original Urban Trial series, which sold over a million units. So even before we knew what kind or genre of game Steel Rats would become, we had some sense of the things we wanted to play with, as well as the added ambition of taking those core ideas even deeper than we’d done previously.

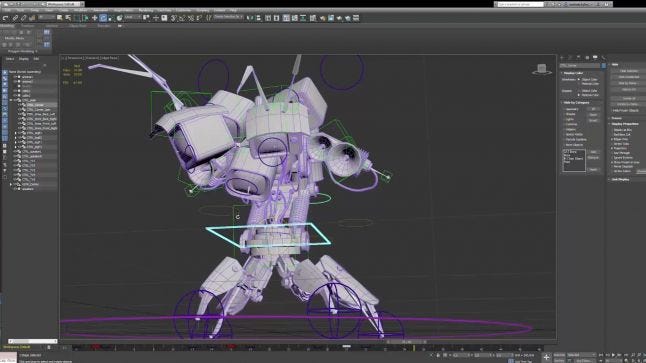

Finding this direction isn’t always as cut and dry as adding one genre to another. Sometimes big discoveries happen when you’re thinking creatively about a past mechanic or asset. We’d worked for years fine-tuning the action and movement of stunt bikes, and it wasn’t until someone thought “what if the bikes could move vertically up and down surfaces?” that the idea of a steampunk-style wheelsaw started to crystallize. It didn’t solve everything all at once, but that one design detail became a rally point from which to think about the game as a whole.

We didn’t stop there either. Even after settling on the mechanic, we kept asking “can we push this idea further?” We started thinking about games like Carmageddon and Twisted Metal where vehicle combat is key, and so the wheelsaw grew to take on three functions: going vertically, speeding up and fighting.

By focusing on what we do best, evolving constantly on the work and knowledge we’ve built to grow into new areas, we’re able to go bigger as a studio each time we start work on a new game without having to worry so much about the competition or data analytics.

Committing to Your Vision

Not leaving ideas on the table carries on past brainstorming into the everyday grind of development, too, as you make sure the concept you’re delivering is a complete experience. We began work on Steel Rats with a short set of priorities: side-scrolling gameplay with a great feel and visuals more realistically detailed than players might expect from a 2.5D game arcade action game.

At that stage, we weren’t really thinking about seizing on the current big game genre or minimizing our risk by making something safe according to the current market. The goal was simply to hone in on something unique to our strengths as a studio. That process isn’t always cost-effective, but we think it’s worth it if you can afford it.

And it isn’t always a simple net loss of resources to invest in your capabilities and toolsets as a studio. Our work on Steel Rats’ bike physics technology, for example, led to us receiving a state grant from the Polish GameINN program worth nearly half a million Euros. Refining the things you’re good at could clinch a contract down the road. There are opportunities out there to capitalize on your collective skills if you keep your head up.

One of the things we did wrong early on in developing Steel Rats was using kinematic movement to drive enemies’ navigation. It was easier to set them up, but the response when hitting them with the bike was very poor. It was late in development when we came to agree this wasn’t good enough, so we went back and implemented physical parameters to drive the AI’s navigation. It was a risky move that wasn’t guaranteed to pay off, but in our minds, the priority was making sure we were sticking to our plan and fully realizing our original ideas.

Now your experiences may vary, and I don’t want to encourage anyone to jeopardize time and money trying to make something work in futility. But it’s also true that just because an idea doesn’t work the first time, doesn’t mean it may never be viable. I can’t think of any major idea that ultimately went unused in Steel Rats, and that’s a good feeling. We committed to the things we wanted to accomplish as a team, and that gives us even more to work with on our next project.

Growing Your Audience

This idea of iterating on and leveraging what you’ve built goes beyond development to marketing and outreach, too. Every time you put out a new game (small feat, I know), you’re not just putting it out into a void. Each release offers the opportunity to build on the brand you’ve already established as a developer with players, press and influencers around the world.

Early on as a studio, we made an effort, simply by necessity to survive, to expand our outreach to regions beyond the United States and Europe. One of the benefits for us was the near-complete separation of these territories from markets in Asia and Latin America in terms of release schedules and communication of consumer information. So we took our time with the flexibility that afforded us. We made careful choices to maximize our investments in each market, lining up publishers that knew how to sell games in their respectives territories while putting time into conferences like China Joy and TGS where you can meet players firsthand.

That effort ultimately paid off in more than one way. About a third of all sales for Urban Trial Freestyle came from Japan. This on its own was invaluable, allowing us to continue making new games. But beyond that, we now had an audience in Japan that knew who we were. So as we prepared for the launch of Steel Rats, we made sure to leverage that built-in leg-up with a physical media release in Japan that the rest of the world didn’t see. That can be a pricey move for an indie game nowadays, but our past successes in the region simply lowered the risk factor for us.

And that’s fitting for a game created with the philosophy that everything that’s come before should be carried forward and built upon further. Your game may end up being a combination of a lot of things when it’s finally out, but often far more important is the formula you choose to start with, not the one you end with.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like