Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How do two teens briefly become some of the best known independent developers in their country? This is the story of ANMA, a fruitful collaboration between two Dutch students, creating memorable games for the MSX computer in the '90s.

[How do two teens briefly become some of the best known independent developers in their country? This is the story of ANMA, a fruitful collaboration between two Dutch students, creating memorable games for the MSX computer in the '90s.]

From time to time the idea of a universal video game platform is still discussed in bars, college dorms, and playgrounds. What innovation might be birthed if Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft decided it would be more lucrative to work in unison than in rivalry? A standardized development format would benefit developers by eliminating cross-platform development costs, while the confusion of what game works with what hardware would be eliminated for the consumer.

It's by no means a new thought. In 1982 a 26-year-old Kazuhiko Nishi, then vice president of Microsoft Japan and director of ASCII Corporation, originated the idea to introduce a standardized computing format. Nishi wanted to replicate the standard that videocassette recorders established with VHS in the computer market, hoping that the platform would become as ubiquitous as television or telephones.

The MSX ("Machines with Software eXchangeability") was the result of his thinking, a universal development platform for which any piece of hardware or software with the MSX logo on it would be compatible with MSX-branded products from other companies.

Despite finding considerable success with five million sales worldwide and launching series as long running as Metal Gear and Bomberman, the MSX failed in its intended mission. By the time the MSX was introduced to America, the Commodore 64 was too firmly established in the public's imagination and households to allow room for a computing hardware standard to take root.

But not before the vision had inspired a young generation of game makers with dreams of making a game that could run on any computer anywhere in the world.

Andre Ligthart and Martijn Maatjens were two such boys. Both aged 15, they were the only youngsters in the small village of Hoogkarspel in North Holland to own an MSX, a fact that brought about their friendship. After two years of hanging out, playing games at each others' houses, Maatjens, a budding composer, suggested that the pair try to make a game demo of their own for the system.

Within four years the pair would have seen their games spread across the Netherlands and into Japan, propelling the young boys to fame within one of the most vibrant and creative indie communities in gaming's short history.

"Between 1984 and 1989 the MSX was a relative mainstream home computer in the Netherlands," explains Ligthart. "It was something of an anomaly as, in the rest of Europe, the MSX wasn't that popular, and in America it was almost unheard of. We started making demos for the system at the end of its lifecycle. At that time, the most professional Dutch software makers already quit the business due to lack of the MSX's popularity."

Inspired by the semi-professional game developers working on the MSX rival Amiga, the pair set-up their own studio, contracting their names together, Andre lending the "AN" and Martijin the "MA" to form the company name: ANMA. In 1989, working out of their parents' homes, work began on what, two years later, would become ANMA's first release, Squeek.

Ligthart handled programming, writing a bespoke program, ANMA's RED (standing for "Recorder and Editor") and custom build interface for Maatjens to connect with a music keyboard for real time music recording. Both boys worked on the graphics, the one aspect of the studio's output in which Ligthart believes they "underperformed."

"The in game graphics were created by Andre and me," explains Maatjens. "We tried to split the work evenly between us. At that time we were looking for someone who could do graphics (in-game, as well as box covers). But we never really found any talented people we wanted to work with."

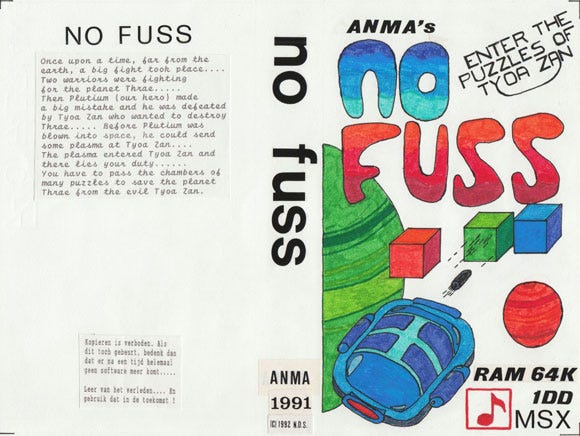

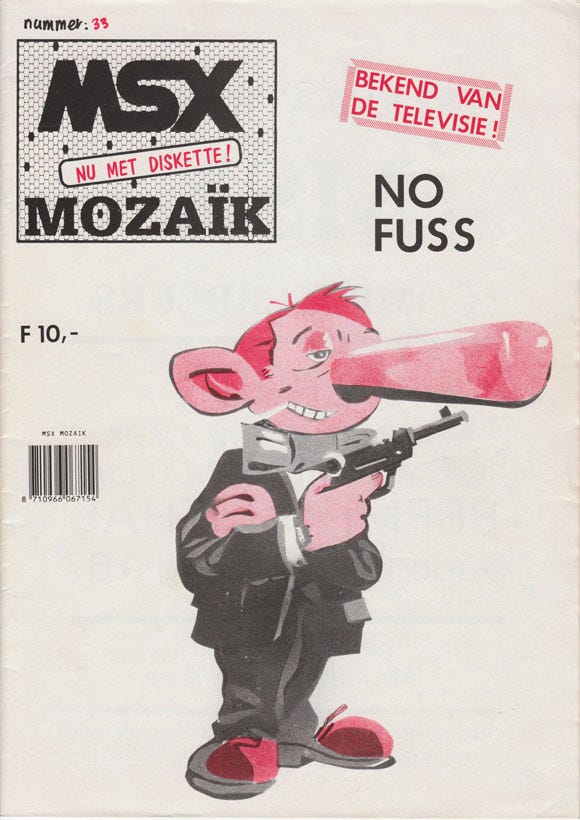

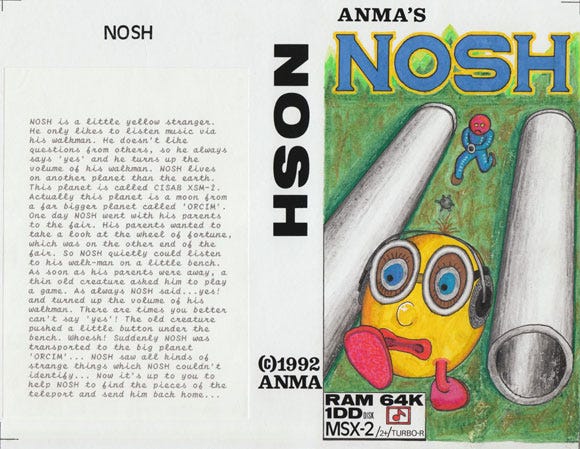

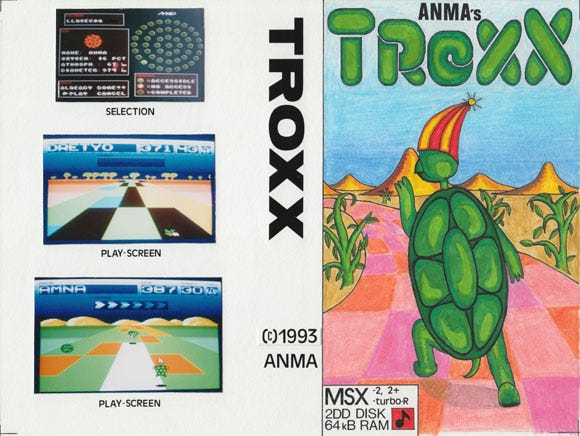

ANMA's games are famous within the MSX scene for their lo-fi indie-esque box art. Hand drawn with pencil and crayon, the artwork is equally revered and ridiculed today.

"We both pitched in on artwork duties," explains Maatjens. "We alternated the box art work from game to game between each other. For one game Andre would draw the front cover, while the next time I did. We also created the instruction booklets for our games by hand.

"It was really a subsidized effort because we took material from our school (where my father was a teacher) to create the booklets. That was lots of fun and at the same time something that just had to be done. We were not much of graphical artists so we were not particularly proud of those box covers."

However, the pair is proud of the game design and programming of their games, which are considered to be among the strongest semi-professional releases for the system.

"I was inspired by programming on the MSX," says Ligthart. "On one hand, because I could challenge myself and express my creativity. On the other hand, I wanted to be technically the best. At that time there were many very cool releases from Japan, especially the Konami games.

"But there were only a few professional Dutch software makers. We were semi-professional, because it started as a hobby and we have never worked full time on our projects. We strived to reach the Japan-like quality. Also, we wanted to build a 'cool' image within the MSX scene, just like many groups did on many other systems."

"The MSX system is a typical system technically as there are so many restrictions in what a programmer can do," he says. "By knowing all ins and outs of all the internal systems/processors a programmer can 'tweak' the system to make the impossible possible.

"That was personally a challenge for me. I started with MSX-BASIC when I was 14 years old. To master programming in machine code was a big hurdle, because it is much more elaborate and difficult than MSX-BASIC.

"The first machine code routine was just to move a sprite from left to right on the screen. I thought that I made an error, because when I started the routine, the sprite was already on the right side. A few moments later, I realized that the routine had executed so quickly that I could not see the sprite moving! That moment I released the potential of machine code programming. It was a special moment for me, after which my creativity started working to imagine what I could make with such a fast language. Today we laugh about that speed, of course..."

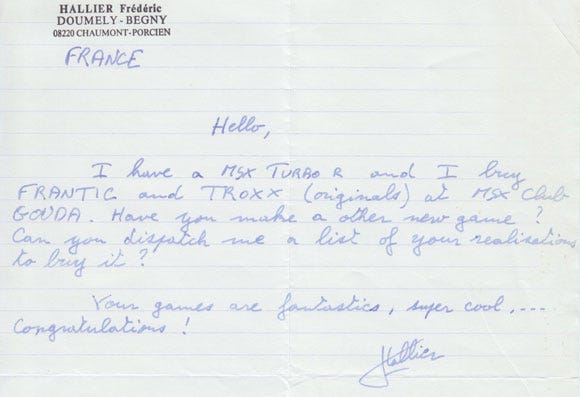

Between 1991 and 1993 ANMA released five games: Squeek (1991), No Fuss (1991), Nosh (1992), Frantic (1992), and Troxx (1993). The pair traveled to computer fairs around the Netherlands selling their games. "We would have mini-crunches as we tried to get a game finished before the next big event," explains Martijin. "We were extremely busy the last few days before the fair to get everything done and make the game error-free so it would be in a state where we could release the game and sell it. Most of the time we didn't plan too well, and spent the last few weeks working overtime a lot to get the game finished."

"We did everything ourselves," explains Maatjens. "We even travelled by train to Amsterdam to buy empty video cases to put our games in from some shady guy. And we copied the artwork for the boxes ourselves. Most of the time the day before the fair we had to put the disks in sleeves, put stickers on them so they would stay in the empty video cases, put a color copy in the sleeve of the video case and slip in the instructions. We'd even rope our parents in to help."

Of course, not everything always went to plan. "One time we discovered a fatal bug in a game while we were at a fair, selling copies," he says. "We tried to fix the bug there and recreate the disks on site. Boy, that was some shitty situation! We probably sold lots of games that day that were faulty…. But we had our contact address always in the booklet and in the game so people could contact us and get a working copy."

For the pair's second title, No Fuss, ANMA even offered a prize incentive to the first player who could prove they beat the game. "In the instruction manual we promised to bring the first player who could prove they completed the game a big pie. A few weeks later we received a postcard from a player with the correct code, so we went out and bought this pie and drove it to his house. A journalist from an MSX magazine came along and took a photo of us presenting it to him."

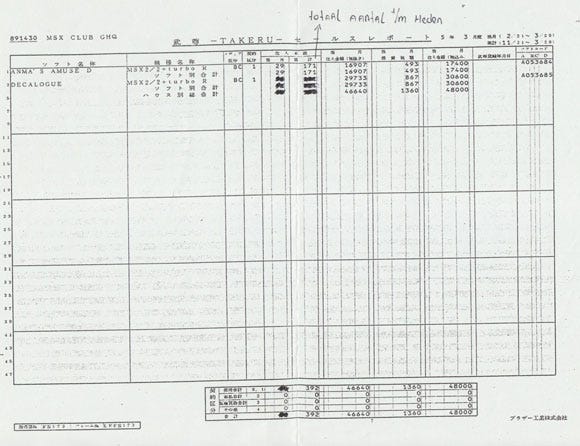

Takeru monthly statement

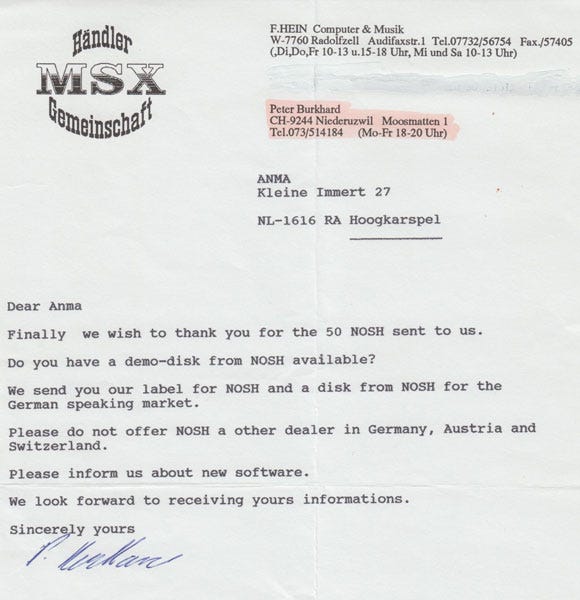

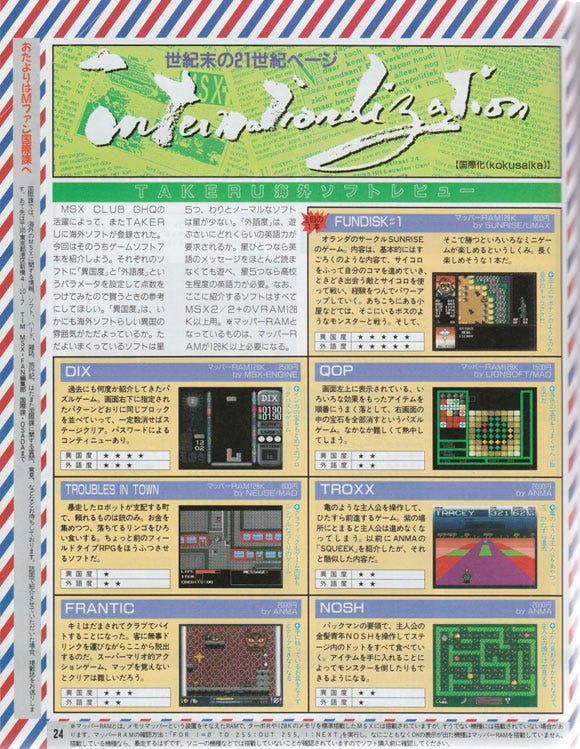

Soon enough, word of ANMA's games had spread across the Netherlands and, even though the MSX scene was fading, the pair attracted interest from publishers wanting to distribute their games across the country, and even overseas. "Several dealers approached us and sold our games in the bigger MSX clubs and through specialist magazines," says Ligthart.

"In the beginning we had trouble selling our games. From our third game onwards, things changed. We became popular and very well known in the scene, partly because of our demos, which were released on many MSX club disks (which were sent to all members of that particular MSX club) and because more MSX magazines were writing about our products. From that time onwards, people called us out of the blue, or spoke to us on the big MSX fairs. So we did not really invest a lot of time in marketing or public relations. We just became a well-established software producer because of the products we made."

One distributor had in-roads to Japan and in 1992 ANMA's games began to be shipped to Tokyo and sold in MSX vending machines across the country, something the boys never thought would have been possible when they first started making games. "The vending machines were run by a company called Takeru," says Ligthart. "Buyers would put the money in and in return receive a piece of low-budget software on a 3.5-inch diskette and a manual which was printed directly."

While many of the professional MSX developers had long left the system for dead, by 1992 the machine still enjoyed a vibrant indie scene across the Netherlands. "I don't know exactly, but somehow MSX kept a very loyal fanbase," explains Ligthart. "I think it was partly due to the relative accessibility of the system. For example, there was a very good BASIC programming language built in, so an amateur could do some interesting programming.

"I think some people were 'attached' to the system and believed in a long-term survival, even though the facts were plainly different. At that time a PC was not so attractive (no music, and 'green' monitors, no 'smooth' games)." The result was a scene of MSX indies, with all the alliances and rivals that go along with it.

"In our demos, we made comments about a lot of our rivals," says Ligthart. "They were both competitors and our 'MSX-friends', so sometimes we made nice comments and sometimes we made quite rough comments about them, because of the competitive element.

"We'd all meet up during the MSX fairs and sometimes between. We also participated in a more local MSX club/fair. We regularly made a special 'MSX Quiz' with questions about the MSX scene and about technical MSX stuff. The winner of the quiz got home with a little prize.

"I had some contact with a few fellow programmers; we sometimes brainstormed or asked questions to each other. But mostly people contacted us (when we peaked in popularity) because they wanted something done, like an article or a release of one of our demos."

Thanks to ANMA's rise in popularity, the boys were regularly featured in MSX magazines. "There was one interview with MSX Engine Magazine I remember," says Ligthart. "The interviewers came to our place. At that time our popularity had peaked and we were very aware about how everyone viewed us. So we answered the questions in a very arrogant manner (in a 'we are the best' and 'ANMA rules' manner). That interview is both cute (because of our age) and embarrassing at the same time…"

However, by 1993, the pair's enthusiasm for creating games was waning. "We were kind of fed up with it," explains Maatjens. "Especially with the last game which is, in my eyes, our most inferior product released. Troxx was was really only done for the money, and we didn't have much fun creating it. So I guess that's why we stopped."

"Yes, that's it," agrees Ligthart. "Also, we could see the MSX slowly fading away in terms of popularity. So we knew that sales could never increase, even if we would make the best game ever. So the potential to grow was not there anymore. We considered moving to a different system, but we would have needed to invest a lot of time to learn a new system, especially as coder."

The pair made enough money from their releases to, as Ligthart puts it, "buy a nice video recorder, a PC, and some other stuff," but sales weren't high enough to mean the two boys could make their hobby their full time vocation.

Both drifted into IT jobs at firms in the Netherlands, losing contact till 2000, when a group of old MSX developers approached Ligthart to encourage them to re-release some of their old titles on the Game Boy Color, whose 8-bit Z80 processor was very similar to that of the MSX. While the Game Boy project stalled, No Fuss may yet resurface, as a friend of Ligthart is currently porting it to iOS.

But in the main, the ANMA dream is consigned to history, the project the product of a set of unique hardware circumstances, and the passion and hard work of two two schoolboys. "I loved that time," says Maatjens. "We had no worries and we were free to be very creative. This interview has brought back so many memories, and reestablished contact between Andre and myself. I still like video games and play them on a routine basis. I sometimes even have played some of our own games on an emulator, just to reminisce."

"Like Martjin, I look back to that time very positively," says Ligthart. "Nowadays I rarely play video games, but about once a year I boot up some MSX titles (including our titles) to enjoy the nostalgia. I have a daughter now (one year old), but when she's ready for it, I will introduce video games to her. Maybe I'll start with my own."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like