The state of educational games in the _ Minecraft_ era

Minecraft, Kerbal Space, and even Civilization all have instructional spin-off versions. But do educators know how to integrate games into the classroom? We got the takes of some educational game devs.

I've heard time and again that educational games are either terrible, uninspired flashcard drivel or endless rehashes of the likes of Oregon Trail, Carmen San Diego, Math Blaster, and Lunar Lander. Yet some of the most-played games in the world are made for the classroom and other learning environments. Still, the stereotype persists that educational game development is some sort of game industry backwater.

Fans and developers of mainstream games — along with games-illiterate educators — are full of suggestions for how to "fix" educational games. But they seldom get to the root of the issue. And moreover, educational games are much more diverse than they typically get credit for.

To gather some insights into what educational games are now, what they should aspire to be in the future, and how effective (or in some cases ineffective) they can be in practice, we reached out to a few leading educational game developers.

Changing perspectives

Filament Games has released a Webby award winning series of science education games with the Smithsonian Institute, and has been the designer behind several of the games released by iCivics, a nonprofit digital education company founded by Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor to teach civics to students in grades 4-12.. Filament co-founder and chief creative officer Dan Norton "When we started the company about a decade or so ago," says Norton, "we were still in a spot where there's lots of concern and worry about whether games were a waste of time, or perhaps they were murder indoctrination devices."

Arrows show the forces affecting your spacecraft in KerbalEDU

That's shifted, but for companies like Filament, SimCity EDU developer GlassLab Games, and KerbalEDU (as well as MinecraftEDU, before Microsoft took over) developer TeacherGaming the evangelizing process is still very much underway. "I would say that right now, the real barrier is that the first thing schools and teachers identify as the main value of games is engagement," says Norton. They get students excited before the 'real' learning begins, and they're siloed off from the rest of the students' activities that day.

"I think that's such a huge waste of the classroom space," says John Krajewski, creative director of Strange Loop Games, "because really, it's a game designer's dream space."

Games can teach systems and relationships in a more interactive and organic way than textbooks. "I think the real value of games is to be able to provide these intermediate identities that ask you to become someone else," says Norton. A game like SimCity or Civilization or Eco can make a student a key stakeholder in a simulation of the system that they need to learn and understand as part of their education.

Learn physiology with Filament Games' Dr. Guts

Learn physiology with Filament Games' Dr. Guts

As part of this shift, research into the efficacy of learning games is moving from questions related to "can games convey important information?" to "what is a good learning game versus a bad learning game?" and "what makes a game succeed in one environment but fail in another?"

Why not just Google It?

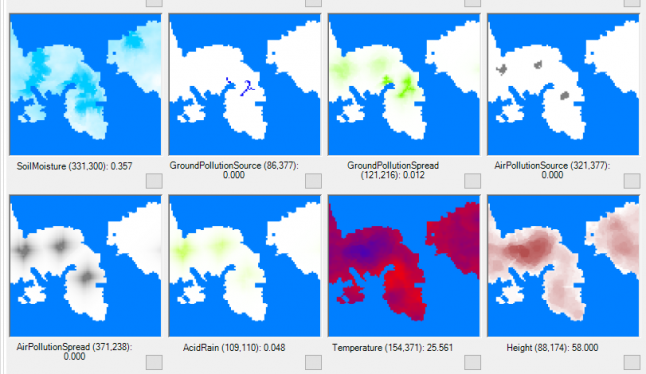

In upcoming ecology-themed online survival game Eco, Strange Loop Games has been granted the freedom to explore what an educational game could be. Krajewski, who worked as Lead AI Programmer for Pandemic prior to founding the company in 2008, says that they're aiming for Eco to present a better way to do educational games. In particular, he wants Eco to show how valuable it can be to create context. He argues that the existing educational system — and by extension most of the educational games that support it — is built around knowledge, which he believes is outdated. "You can Google any knowledge you need," he says.

Strange Loop Games' Eco

Instead, Krajewski says education should be about creating context that shows people how and why knowledge is useful. "I think that's something that's really missing in school a lot of times," he continues. "Like I think back to how math was taught: here's an equation, memorize this quadratic formula, then you plug and chug the numbers and get the answer. People can do it, but by the end of the class they hate math." Krajewski believes people develop math phobia because they have no context, and no reason to care. Worse, he argues, games that are made to reinforce this style of learning — to memorize facts or gain specific fact-based knowledge — can have the effect of "de-educating."

Strange Loop Games' Eco

Strange Loop Games' Eco

"[Schools] were designed in the industrial era to create workers and people who could just churn out things," he says. "Whereas we need something much more entrepreneurial and more collaboration-focused, leadership-focused, social-focused." Eco is about showing that games not only can do that but also do it way better than traditional education.

Harder than you know

Norton of Filament Games says that designing games for education is continues to be very challenging. In some cases, it can even prove harder than commercial game design.

While most game designers can focus on making whatever decisions provide the best player engagement, an educational game designer must always consider a set of pre-determined learning objectives as they strive to maximize player engagement. They can shift genres and mechanics at will, provided they stay within budget and scheduling constraints. But "a learning game has to be about the thing it was intended to be about," he explains. Norton finds it extremely satisfying to face that challenge project after project — to search for ways to teach players about, say, cancer treatment devices or physiology or different states of matter, or whatever else, without resorting to flash cards and big information dumps.

Filament Games' Webby Award honoree Morphy

The way it generally works is that the developer and the client — either a funding body that issues grants or the specific group or organization that will use the game — agree on a high-level goal for the game. It's essentially about deciding what change they want to see in the players, or put another way, what they want to be different once the game is finished. Sometimes there'll be strict learning objectives to meet, such as when the game needs to fit into an existing curriculum, but other times there's more flexibility and the game need only fit a broader educational theme.

Collaboration is key

Norton and Krajewski both emphasize that good educational game design — whether for the classroom or elsewhere — needs rich internal feedback loops and collaborative systems that get players talking to each other and working together to solve problems. These are also hallmarks of good entertainment game design, but here they differ in two key ways: the relevance of systems to the real world and the nature of the feedback.

Getting good at Call of Duty or League of Legends doesn't translate into useful real-world knowledge; the systems they teach aren't applicable outside of games. They also have very high skill ceilings. Unlike entertainment games, which typically attempt to separate players of different skill levels (and still wind up having new players learn by dying constantly), educational games must cater simultaneously to players of wildly varied skill levels.

Norton argues that it doesn't work to simply take a system from a popular role-playing game, shooter, or MOBA and apply it to educational material, because people who don't normally play these kinds of games tend to have a much lower tolerance for failure.

iCivics

Educational games don't need to be strictly accurate, either. Consider a game about history, like the upcoming CivilizationEDU spin-off of Civilization V, and Energy City, which is about developing different types of energy to support a city as it grows. Neither reflects reality. Both use made up data. Both "lie" about the details in their simulation. But both have great educational value. The former encourages the player to consider how things like technology, culture, and war shape history, and to develop an interest in key historical figures and societies. The latter drives the player toward an understanding that energy technologies change over time and that cities can produce and use energy in different or better ways.

What's really important is that the feedback loops and collaborative systems focus in on the big picture — the how and why, not the what and when, because the knowledge that educational game developers (and increasingly educational institutions) want players to gain is in context rather than facts. Then maybe the players will be motivated to go learn the facts themselves.

Energy CIty

Energy CIty

"Learning game design is a sort of celebration of the idea that it's wonderful to learn new things," says Norton. "The act of learning is an intrinsically pleasurable, worthwhile endeavor. So if we can get people to knock down their barriers in their own heads about what's worth knowing and what's not worth knowing and get them to be open to new aspects of the world, that's a huge victory."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)