Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Tristan Donovan presents the latest of the interviews which formed his book Replay; this revealing installment is with Ray Kassar, the executive who took Atari off of Nolan Bushnell's hands and shepherded it through the boom years.

[In the writing of his history of the video game industry, Replay, author Tristan Donovan conducted a series of important interviews which were only briefly excerpted in the text. Gamasutra is happy to here present the full text of his interview with 2600-era Atari exec Ray Kassar.]

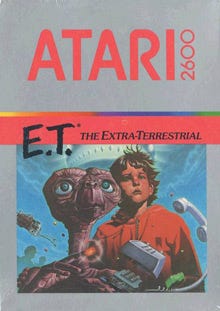

A reluctant recruit from the textiles industry, Ray Kassar took charge of Atari in the late 1970s and led it to its height. But while he turned the scrappy but pioneering game firm into one of the world's largest companies and got millions to buy VCS 2600s, his legacy is tempered by Atari's spectacular collapse, the infamous E.T. disaster, and his description of Atari game designers as "high-strung prima donnas".

In this interview, Kassar explains why his reputation as an enemy of game designers is underserved and why Atari needed him.

You had been working in the textiles industry prior to Atari, so how did you end up being offered the Atari job, and what was your reaction to the offer?

Ray Kassar: The Atari job was offered to me from a recommendation of a friend who was working at Warner Communications. My reaction was that I had no interest at all in what he was offering.

If you weren't really interested, why did you accept it?

RK: My friend insisted that I meet with Manny Gerard, who was one of the presidents of Warner. And, after four hours of talk, I said I would only take it under certain conditions. They agreed to all my conditions. I said I'd only go for a couple of weeks.

What was your opinion of video games at the time? Had you played them before?

RK: I really didn't have any opinion about video games. I had not played video games before.

Manny told me you were hired to try and bring some much-needed management discipline to Atari. How in need of proper management was the company at the time you joined?

RK: The company had no infrastructure. There was no chief financial officer; there was no manufacturing person, no human resources. There was nothing. The company was totally dysfunctional.

Did you know it was that bad when you agreed to go in?

RK: No. I had no idea.

Must have been a bit of a shock, then...

RK: That's to say the least. To give you an example, when I arrived there on the first day, I was dressed in a business suit and a tie and I met Nolan Bushnell. He had a T-shirt on. The T-shirt said: "I love to fuck." That was my introduction to Atari.

One of the legends about Atari is that Nolan Bushnell offered you a cannabis joint at a management meeting shortly after you joined the company. What was your reaction to that, and how did you deal with the wider culture of drug use at Atari?

RK: Yes, this is true. I told Bushnell that I was busy. I got up and left the meeting... It was unbelievable. Dealing with the drug problem was an ongoing challenge. You know, we did the best we could, but it was a tough problem: we had 12,000 people at one point.

Do you think it was a problem particular to Atari?

RK: No, no. It was California: everybody smoked pot. It was not an endemic problem, it didn't -- in my opinion -- affect anybody's work. But it was a bit of a problem and every company had that problem.

How was the 2600 console performing at the time when you joined Atari in February 1978? From what I can tell its success was far from guaranteed at the time.

How was the 2600 console performing at the time when you joined Atari in February 1978? From what I can tell its success was far from guaranteed at the time.

RK: The 2600 was selling but not in any great volume. The problem was quality, which was terrible. The return rate was excessively high.

The quality of the machines, or the games, or something else?

RK: It was the hardware.

For Christmas 1978 you decided Atari should throw everything it had at making the 2600 a success. How much of a "do-or-die" situation was that Christmas for Atari?

RK: The key decision we made was to advertise the product and, with strong follow-up by the sales reps, it wasn't a do-or-die situation. And I had the full support of Warner on this.

Nolan felt Atari should give up on the 2600 and said so at a Warner board meeting just before Christmas 1978. Why did you feel he was wrong?

RK: I had a strong belief in the product, and I just focused on fixing all the problems.

Nolan left Atari very soon after that meeting in what seemed a fairly mutual parting of ways. Why did he need to go?

RK: I couldn't have accomplished what I did with Nolan in the picture. Atari couldn't have two bosses. Well, two people can't run a company. I mean, one person has to have the final responsibility. Nolan would say one thing and I would say another thing. How do you resolve that? Either they're going to have faith in him or me. You have to have either him or me.

Why did you stay? You said you only came for a couple of weeks originally.

RK: I came out there very reluctantly. I mean, I live in New York, I love New York; I had no interest in living in California.

So was it a relief to have Nolan out of the way?

RK: Yes.

From Christmas 1979 until the summer of 1982, Atari grew at a massive rate. How hard was it to manage what was claimed to be the fastest growing company in U.S. history, at that point?

RK: It was very challenging, and at the time my life was consumed with making Atari successful. We all put in lots and lots of hours.

During that time, there was disquiet among Atari's game designers about the lack of public credit they got, and you told Fortune magazine that these disgruntled employees were "high-strung prima donnas".

It's also claimed that you said they shouldn't be treated any differently to the towel designers you used to work with. What was behind your thinking, and do you think that was a mistake in retrospect?

RK: I doubt that I ever compared our designers to towel designers. In retrospect, it was probably a mistake to call our designers "high-strung prima donnas". Actually, when I said that, it was an off-the-record comment that unfortunately got on the record.

But, you know, I had great respect for the designers. There's no mistake about that. So that is a totally blown-up image of me by engineers who really hated the fact that I wasn't an engineer and that I came from New York.

Not being American myself, is there quite a difference in style between people from the East Coast and West Coast?

RK: Well, yes. I mean, we're all more serious in the East. You have a job and you do it the best you can and, you know, it's not a playground. In California at that time, things were very casual. They still are. That's okay; that wasn't a problem for me. It was just that somebody had to be the grown-up. They were a bunch of kids playing games.

So why did you think they were high-strung prima donnas?

RK: Well it's the nature of programmers. They're like artists. I remember once this particularly very bright programmer came to see me and I spent five hours with him because he was so critical, crucial. He was reading poetry to me. It was, you know, a little... off the wall. But he was a great programmer, and that's all I cared about. He'd come in at midnight and work until seven in the morning. And go home and sleep and come back at four in the afternoon. I didn't care as long as he produced.

Was he reading his own poetry?

RK: His own poetry. And, you know, he said, "We've had the wrong impression of you, you really do care." I did a lot of things like that, that really nobody knows. I mean I really did all I could to encourage the programmers, to coddle them, to share the love, cheer them up, inspire them, you name it. I mean without the games, we wouldn't have had a business. So they had a lot of respect. They were left alone, they did what they pleased. As long as they produced, it was fine by me.

One of the people who left was Al Alcorn, who went after you stopped work on his hologram console project, the Cosmos. Why did you shut that down?

One of the people who left was Al Alcorn, who went after you stopped work on his hologram console project, the Cosmos. Why did you shut that down?

RK: The program was costly and we really weren't making any progress. I felt it was really distracting us from our main, core business.

Was it a big loss having someone like Al go? He was the last of the original Atari team.

RK: Alcorn was a very nice guy. I got along very well with him, but he just wanted to leave. You know, it was a different company that I was forming.

He wanted to play and I had no time to play, I had so many problems to resolve. [Laughs] But he was a good guy, I liked Alcorn.

Atari's home computer division seemed to get treated as a Cinderella operation. Did it lose out because of Atari's fast growth, or were you avoiding anything that could harm the sales of the 2600?

RK: The computer division was up against tough competition. We decided that it would be better to focus on our video games.

The 2600 also faced competition from Mattel's Intellivision and, later, the ColecoVision. How much of threat were these systems?

RK: Mattel was a tougher competitor, but it wasn't a serious competitor.

How did the 2600 perform outside the U.S., particularly in Europe and Japan?

RK: The 2600 did very well in Europe. It didn't do so well in Japan for obvious reasons; you know, the Japanese have their own video game history. In Europe there were good sales, but nothing like the U.S.

The successor to the 2600, the Atari 5200, performed poorly at retail. What mistakes were made?

RK: The 5200 lacked the technology improvements that the market was looking for. I think that was the basic problem.

Let's move onto the crash that hit the industry. Atari's E.T. game has become a symbol of the U.S. game industry's collapse at that time. As I understand it Steve Ross, Warner's chairman, forced you to rush the development and produce too many copies. Is that correct?

RK: Yes, it's correct that Ross forced me to make E.T. I remember, he called me and said, "I've guaranteed Spielberg $25 million to work on this project." I said, "Steve, we've never guaranteed anybody any money, why would you want to guarantee $25 million? First of all, I think it's going to be impossible to produce a real big hit because it's not an action story."

But he overruled me. The other problem was we didn't have enough lead time to get the chips, the semi-conductor chips. This was in August. He wanted it for Christmas. Normally, you know, we had a six-month lead time.

It was reported that so many copies of E.T. were unsold or returned that the cartridges were eventually dumped in a New Mexico landfill. Do you know if that's the case?

RK: Well, we made about 5 million copies, almost 5 million copies of E.T. Most of them were returned. I told Steve it was ridiculous to make so many because I really didn't think it was going to be a big seller, but I remember he got very annoyed. He said: "No, no, that's what we have to do."

So we made almost 5 million, most of them were returned, came back from the retailers. I never heard about the New Mexico dumping. [Ed. note: Kassar had left Atari by the time the company dumped its excess/damaged/returned stock, including E.T. cartridges, in the landfill.]

Atari's fourth quarter 1982 results were below analyst growth expectations, and prompted a collapse in share price that really marked the start of the U.S. game industry crash. What caused these disappointing results?

Atari's fourth quarter 1982 results were below analyst growth expectations, and prompted a collapse in share price that really marked the start of the U.S. game industry crash. What caused these disappointing results?

RK: The fourth quarter reflected the returns that were beginning to come in on our E.T. product. That was the problem.

You left Atari in July 1983. Did you resign or were you fired?

RK: I was fired. Of course, the papers said that I resigned, but I was fired. Manny called me to come to New York. He was the one who fired me, not Steve, because Steve could never confront anyone for firing.

What was the reason he gave for firing you?

RK: Because they tried to blame me for the E.T. fiasco. Somebody had to be the fall guy and it wasn't going to be Steve; he was the chairman of Warner. I was just chairman of one of their subsidiaries. So you know, somebody had to be the fall guy and it was me.

Incidentally, before this happened I offered to resign, because I had sensed Steve was very unhappy with me. I said, "Steve, if you want me to leave I'd be very happy to leave. It's been a great run, you know, I have no regrets and I'm just sorry we don't agree on things." But, you know, he couldn't face up to tell me, "Yes I would really like that."

After being fired I went to London for a week, came back and Manny called me. He said, "Steve would like you to come back for another three months because we haven't found a replacement for you yet." I said, "Manny, you've got to be kidding. You mean, you fired me, and didn't have a replacement? And now you want me to come back and stay there another three months? You've got to be crazy. Of course not."

Did you feel it was a relief to leave Atari?

RK: I did feel relieved, in a sense. But it was a great experience and I had a wonderful time. It was one of the best periods of my life, so I have no regrets at all. I only have really fond memories, we had a terrific bunch of guys, we accomplished a lot.

In a lot of the stories of Atari's history you get painted as the corporate guy who came along, changed the company culture and then it went down the pan. Does that bother you?

RK: Well, of course it bothers me, because it's not true! E.T. was the beginning of the end. It was something we all were against. It wasn't just me. We were all against it. The programmers thought I was crazy. They said, "We can't produce a game in two to three months! It's crazy." So we rushed. It was a fiasco.

What I did was turn Atari into a business. When I got there, it was kind of a playground, a bunch of engineers who loved to play games. It wasn't about the business, the quality of the product, the returns, the advertising, the marketing, none of those things. So they say what they will, it really doesn't bother me too much, because I know it's not true and anyone with common sense, if you thought about it for two seconds, would realize what I did. So there you are.

I like Bushnell, you know. I have nothing against him personally. He's a charming guy, very bright guy, very capable and, after all, he started the whole thing; I didn't. When I got there it was a mess and they were losing money. When I got there the company was doing about $75 million a year, losing about $15 million. Within three years we were $3 billion in sales, and we were the fastest-growing company in the world at that time. So that's not too bad.

That's big. Not many people can say that...

RK: No. [Laughs] But I do give Nolan a lot of credit because he was the founder and I do respect that. I think I did him a very big favor because he would have destroyed himself. Warner wouldn't have put up with it [as it was].

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like