Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Unity is adjusting its naming convention for future versions of the software and rolling out public access to its generative AI tools.

Today at Unite 2023 in Amsterdam, Unity unveiled new details on what it is now calling Unity 6—the next version of the game engine software that will be available in 2024. Starting with this version, Unity is shifting to a number-based naming convention, moving away from the "LTS" (Long Term Support) naming format, which also listed the year that version of the software was developed in.

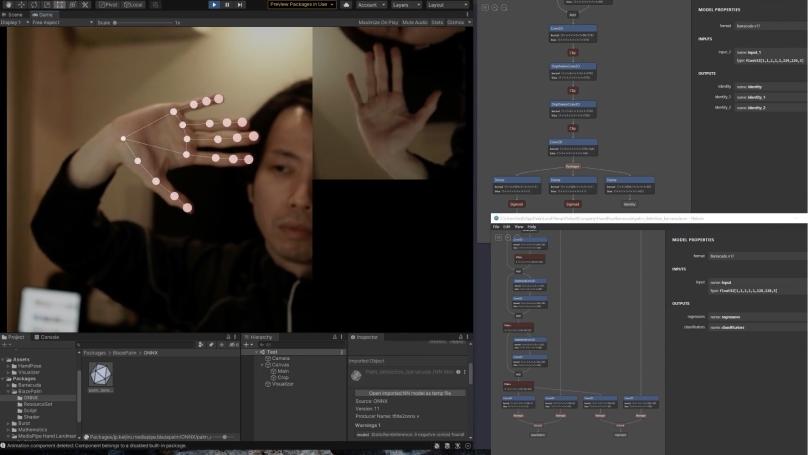

Unity 6 will contain a number of software and quality-of-life updates like the debut of Unity Cloud. Most notably it will include the early access rollout of Unity's two major generative AI tools: Unity Muse and Unity Sentis. Muse is an AI content creation tool that allows developers to create assets and animations "faster, without interrupting their workflows." Unity Sentis is a runtime inference engine that allows developers to integrate neural networks in their game "on any platform."

Developers are likely to be keenly interested in what benefits Unity 6 has to offer since this will be the first version of the software that will charge high-earning developers a fee based on either "initial engagements" by players or a percentage of their revenue, whichever is lower. The structure of this fee program was introduced after an initial install-based Runtime Fee was roundly rejected by the developer community.

Unity Create president Marc Whitten—who both made the case for the Runtime Fee and was the public face of Unity's apology over its rollout—explained to Game Developer that the move to a number-based naming system is meant to communicate to developers precisely which version of Unity they are operating on, and which versions of the software will require developers to pay the revenue fee.

It's Unity's first step into a world where it will be gathering post-launch revenue from developers—and its first opportunity to win back long-eroding trust.

(Our conversation with Whitten took place before Unity revealed to shareholders that it expects to restructure its business in the coming years, with layoffs being "likely," and that its new version of the Runtime Fee will not deliver strong returns in 2024).

Whitten told Game Developer that the company is focused on making Unity 6 "the best version of Unity that's ever existed"—a claim that will certainly be tested since, as he noted, this version will be the one that has "a different business model associated with it." He made additional comments that indicated the Unity LTS naming convention may have been causing some communication difficulties for some time.

"Frankly I never liked the yearly naming model, because it's always this weird thing where the LTS came out [in a different year] than the one it was named for," he said. He said the new naming system should be more "consistent and clean."

Developers used to operating on the experimental Tech Stream of Unity should still expect some form of that model to be accessible in the years ahead. Whitten implied that some updates to that process may be revealed in its Unite Create roadmap session, but declined to share specifics on our call.

We were interested in prodding Whitten on one topic we heard about from developers during the Runtime Fee debacle—which is that some developers were beginning to experience a lack of stability on LTS versions of Unity, even though the company promised it would be the most stable version of the software. The worry was that Unity had become so stretched thin (and so overinvested in higher-earning services) that it was letting the LTS stagnate.

Whitten responded to that query by saying the company will be "massively focused" on stability and performance of Unity 6, and that as before, it intends to continue making bugfixes for older LTS-named versions of Unity even as it moves ahead.

He did inform us that according to Unity's metrics, LTS stability has been "up" year-over-year for the last several years. "That doesn't mean that there aren't bugs that shouldn't be there, and we need to get them fixed."

Whitten said that when he's in various conversations with Unity developers, the most common feature requests he receives are ones asking to improve speed of iteration, performance, and stability. "I believe that has to be the fundamental core for us—that we are constantly making those metrics better."

Unlike Microsoft, which was very eager to tout the use of generative AI for content creation in its recent announcements, Whitten chose to spotlight more granular use-cases in what uses he saw for Unity Muse and Unity Sentis. He said that earlier in the year (when he declared that AI would be a "disruption" for the game industry) he felt most excited about developers using Unity Muse's natural language input that would let developers tell a chatbot what features they put in their game.

Here, he was more eager to talk about how these tools integrated into functions like Unity Texture, describing how developers could use Muse as a "multi-modal" input to quickly pull up a texture mix, experiment with it, try it on a model, and change it quickly using Muse-powered sliders.

Developers who have been wary about the data ownership issues with generative AI tools (that are laden with risks of copyright violation) should, in theory, feel secure using Muse and Sentis. "There's a real focus on making sure that there's an understanding of the data that builds the models," Whitten said. "Texture uses our data—data we have the rights to—and we created a synthetic dataset on top of that with variations so you can build from there."

Image via Unity

Said variations would hopefully ensure that say, your AI-generated textures don't look exactly the same as another developer's AI-generated textures.

Whitten did share some exciting use-cases for Sentis that he said he hadn't conceived of when early access to the technology rolled out earlier this year. "What's surprised me is people are using a lot of small and bespoke neural networks to try and drive different results," he said. The two examples he gave were from a virtual reality meditation app and in a test version of Pong.

In the VR meditation app, the developer was able to use a Sentis and a specific neural network to measure the user's breathing and offer corrections to better help them meditate, turning a Meta Quest headset into a headset with a "breathing sensor."

In the Pong example, he described how a developer used Blender to generate "a million frames" of what the game might look like with full ray tracing, and then made a version of the game that captured the data on ball and paddle positions and then used the neural network to generate frames that gave it the look of a fully ray-traced game. "What that means is there's no game objects," he said. "All of what you would think of in Unity for building that—they've actually replaced it at runtime with [a system] that takes the inputs and [runs] a neural network to create this thing."

The use cases Whitten described are genuinely interesting, but it's worth scrutinizing the kinds of generative AI topics he came prepared to discuss. In the last year, executives and boosters of the technology have crowed about how the technology might replace developers or lead to the creation of fully-responsive NPCs in games that could generate original dialogue and quests.

Whitten did refer to large language models that may help NPCs "come to life" (and pitched the idea of a game like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim where very NPC is "an individual AI agent," which frankly does not sound very fun) but his more modest description of Unity Sentis to developers appeared more aimed at exploring the use of improving existing tools and developing new tech possibilities.

Such language shifts from industry leaders are critical to sussing out what aspects of generative AI technology will be useful for the world of game development—and what elements will turn out to be just smoke and mirrors.

Unity's need to rebuild trust among game developers after the Runtime Fee fiasco will likely mean that any fruitless generative AI tools in Unity 6 will not be welcomed by developers as a worthwhile tradeoff for the newly-imposed fees.

Whitten closed his chat with us by saying the company is committed to listening to the Unity developer community—though he did note said community includes developers of all stripes, from those making hypercasual games to indie games on PC to manufacturers and VR meditation app makers. All of whom have different needs—and all of whom may have vastly different reactions to the new updates in Unity 6.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like