Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

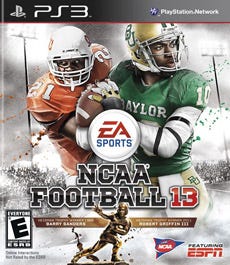

Rutgers professor and lawyer Greg Lastowka explains why he believes that EA should prevail in its case against Rutgers quarterback Ryan Hart, who's suing the company because his likeness has appeared in NCAA Football -- and the considers the broad implications of a loss or a win for Hart.

[Rutgers professor and lawyer Greg Lastowka explains why he believes that EA should prevail in its case against Rutgers quarterback Ryan Hart, who's suing the company because his likeness has appeared in NCAA Football -- and the considers the broad implications of a loss or a win for Hart.]

Ryan Hart is one of the most famous quarterbacks in the recent history of Rutgers football. He led the 2005 Scarlet Knights to the Insight Bowl, the first bowl game that Rutgers had played in decades.

Four years later, Hart took on another leading role, this time as the named plaintiff in a class action lawsuit against Electronic Arts. Hart's legal team claims that EA has infringed Hart's "right of publicity". Hart also claims EA infringed the rights of other college players by including their information and statistics in EA's college football games without authorization.

Specifically, Hart's complaint is about a nameless quarterback that appears on the Rutgers team in EA's 2004, 2005, and 2006 games. The player wears jersey number 13, is six feet and two inches tall, weighs 197 pounds, wears a wristband on his left wrist, and hails from Florida.

Not coincidentally, that is all true of Ryan Hart. Since the EA games additionally have allowed players to fill in names on team rosters, many people play the nameless Ryan Hart under the name Ryan Hart. Downloadable and accurate rosters of all the featured college teams are currently shared online.

Last fall, a federal district court dismissed Hart's case, explaining that the free speech rights of Electronic Arts trumped Hart's right of publicity claims. Hart appealed and now is arguing his case before a federal appellate court in Philadelphia. Along with several other professors, I submitted a brief to the court explaining why Hart should lose his appeal. Below, I'll explain why.

It's important to see, at the outset, that Hart has a good reason to be bothered by the money being made off his identity. The court that dismissed his case suggested he had been treated unfairly and stated it "appreciates the plight of college players." That plight is primarily about the way money works in college sports.

It's important to see, at the outset, that Hart has a good reason to be bothered by the money being made off his identity. The court that dismissed his case suggested he had been treated unfairly and stated it "appreciates the plight of college players." That plight is primarily about the way money works in college sports.

Ryan Hart was a star Rutgers player during an era when the university was building a new hundred million dollar stadium and negotiating a million-dollar-plus contract with the football team's coach. Universities don't spend money like that without anticipating some significant returns on their expenditures. Yet despite all the money flowing into Rutgers football, Ryan Hart was never paid a dime.

Indeed, Hart could not be paid, because the rules of the National Collegiate Athletics Association forced Hart to be an "amateur". The NCAA excludes any player who takes money from playing NCAA sports. The NCAA's President, Mark Emmert, recently explained that it is "grossly unacceptable and inappropriate to pay players".

Yet while the NCAA says this, its licensing agent, the Collegiate Licensing Company, rakes in over four billion dollars a year in revenues. Since 2005, the CLC has granted EA an exclusive license to make its NCAA football games. When EA includes NFL players in its games, the revenues are shared with those players. The NCAA, however, doesn't share its revenues with players like Hart.

Many people, myself included, think that Hart has been exploited. Undergraduate athletes are too often used and abused as free labor to build multi-million dollar entertainment and licensing empires. We can't shrug this off by thinking that college sports are training grounds for professional play, since it is extremely rare for NCAA players to turn pro. Take Ryan Hart, for example. After graduating from Rutgers, he tried out for the New York Giants, but he did not make the cut. Today, he works in the insurance industry. Even for many star players, this is the standard story.

Hart isn't the only former college athlete attacking the NCAA's game licensing practices. At the same time that Hart filed his suit, Sam Keller, another former NCAA football star, brought an almost identical lawsuit in California. An early ruling in Keller's case suggested that EA had indeed violated Keller's publicity rights by including his statistics and other information in its games. Keller's case is now consolidated with many similar cases by NCAA athletes complaining about the exploitation of their publicity rights. The main difference between these cases and Hart's cases is that the California cases rely on antitrust law and name the NCAA directly a named defendant.

My problem with all of these college sports and video game cases, however, is that they rely on the right of publicity, a new property right that threatens to constrain creative freedom in the games industry.

While the NCAA amateurism rules are a mess, the right of publicity that Hart and Keller are asserting is an additional mess that has little promise of straightening out the NCAA mess. Unlike most people, I am fairly familiar with the ins and outs of the right of publicity. The basic concept is simple. As the court in Hart's case said, "a celebrity has the right to capitalize on his persona" and can prohibit "the unauthorized use of that persona for commercial gain".

To take a simple example, if I sold a coffee mug bearing Ryan Hart's name and picture, Hart would have a claim for damages against me for exploiting his right of publicity. The damages would be a standard licensing fee, though for some celebrities those fees can amount to millions of dollars.

What's so bad about selling a coffee mug with a celebrity's picture? A century ago, the answer would have been "nothing". Before the rise of our celebrity-saturated 20th century, there was no right of publicity.

By the middle of the century, however, many courts had started to recognize a right of celebrities to capitalize on the commercial value of their names. And more often than not, these celebrities were sports celebrities. In the famous 1953 case of Haelan Laboratories v Topps Chewing Gum, a New York court stated that professional baseball players could prevent the sale of trading cards carrying their likenesses.

What changed in 1953 that justified the creation of a new right of publicity? Not much, actually. Usually, with intellectual property rights, the law tries to create incentives for some sort of creative production. We grant patents to encourage new inventions. We grant copyrights to encourage the production of new stories, music, and video games. But why should we grant publicity rights? Does anyone really believe that publicity rights are needed to create celebrities?

There is no commonly accepted theory that justifies the right of publicity. And for every question you ask about the right, you can find fifty different answers. While federal law grants most intellectual property rights, e.g. patents & copyrights, the right of publicity is a creature of state law. This means a different set of rules applies in every state. In some states, like Tennessee, the right of publicity can be perpetual. (No doubt the estate of Elvis Presley was happy about this.) In some states there are statutes that protect the right. In other states, judges created the law. So there is no right of publicity, to be precise. Instead, there are 50 different rights of publicity.

Today, many states -- California is one of the worst culprits -- have let publicity rights grow so large that they threaten artistic creativity. Indeed, celebrities have often sued companies simply for referring to them.

In one of the most famous publicity cases, game show hostess Vanna White sued Samsung for putting a blonde wig on a robot in a way that recalled her job turning letters. White claimed the robot evoked her identity and infringed her right of publicity. A federal court agreed.

Paris Hilton recently sued Hallmark for selling a card where a cartoon waitress exclaimed "That's Hot!" She prevailed when Hallmark tried to dismiss that case, and ultimately extracted a settlement. Even babies are marketable celebrities; Jay-Z and Beyonce have taken legal steps to ensure that their infant, Blue Ivy, can capitalize on her trademarked name. Does all of this really benefit society?

Too often, the right of publicity limits the freedom of creative artists. For instance, in the case of Doe v. McFarlane, a Missouri court found that Todd McFarlane, creator of the Spawn comic book series, had infringed on the publicity rights of Anthony Twistelli, a hockey player for the St. Louis Blues. McFarlane had not used Twistelli's likeness to sell comic books. Instead, he had simply named a minor character in his book "Tony Twist". For that unauthorized "exploitation" of Twistelli's publicity rights, a jury required McFarlane to pay fifteen million dollars in damages. On appeal, a court upheld the verdict. So how free is a comic book artist if he has to license the names of his characters?

In theory, publicity rights are supposed to be balanced by courts with protections for free speech. But as the McFarlane case and others demonstrate, this balancing too often favors celebrity rights over speech rights. Given the risk of infringement, it seems likely that artistic creators will simply censor themselves by limiting their creative options. If you don't have the resources of EA, do you really want to risk fighting and losing a lawsuit?

This is a particular problem with video games, given that courts have routinely equated games with coffee mugs. If you want the in-depth legal story, this article by Professors William Ford and Raizel Liebler is hot off the press and it does an excellent job of explaining how publicity rights relate to games.

The short story is that games, like comic books, have historically been treated as a second-class genre. However, the Supreme Court's recent decision in Brown v. EMA should have changed that understanding.

In that case, Justice Scalia said:

"Like the protected books, plays, and movies that preceded them, video games communicate ideas -- and even social messages -- through many familiar literary devices (such as characters, dialogue, plot, and music) and through features distinctive to the medium (such as the player's interaction with the virtual world). That suffices to confer First Amendment protection."

Like Professors Ford and Liebler, I believe that publicity rights in games are too broad today. Accordingly, I think the appellate court in the Hart case should choose a balancing test that favors free speech over publicity rights. The best test available is the "Rogers" balancing test, named after a case involving the celebrity Ginger Rogers.

The Rogers test has two steps. First, it asks if the use of the celebrity identity is "artistically relevant" to the work in question. (In Hart's case, the answer is clearly "yes"; the game is about the history of NCAA sports, and Hart played a role in that history.) The second step of the Rogers test asks if the reference to the celebrity is explicitly misleading. (In Hart's case, the answer is "no"; there is nothing misleading about the inclusion of Hart in the game.) If the Rogers test is applied to the Hart case, EA should prevail.

However, if another balancing test is used, the result in Hart could follow the result in the cases of Vanna White, Paris Hilton, Anthony Twistelli, and Sam Keller. As Ford and Liebler explain, allowing the right of publicity to control video game content could severely limit expressive freedoms.

However, if another balancing test is used, the result in Hart could follow the result in the cases of Vanna White, Paris Hilton, Anthony Twistelli, and Sam Keller. As Ford and Liebler explain, allowing the right of publicity to control video game content could severely limit expressive freedoms.

Historical war games might be required to seek licenses from the heirs of famous generals. Games that reference gangsters might need licenses from the families of the deceased criminals. And good luck with "newsgames" that offer commentary on contemporary celebrities.

In a world of licensed identities, only those game developers capable of paying licensing fees would be able to make games that refer to actual people of historical interest. Ironically, even though EA has benefited from its exclusive license to make NCAA football games, a ruling against EA might create further barriers to competition and allow EA and other companies to obtain exclusive rights to even broader swaths of the market for video games.

The Hart case is important. If our courts fail to curb the accelerating growth of publicity rights, licensing requirements will threaten creative freedoms. Ryan Hart has a valid reason to complain about his commercial exploitation. If the NCAA can be required to treat its players more fairly, we can solve that problem. But courts should not try to fix the NCAA by endorsing video game censorship.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like