The Designer's Notebook: Employees Leaving? Deal With It!

Are perfectly good employees leaving your projects at the worst possible times? Veteran designer Ernest Adams has no sympathy for you, and he'll tell you why in the latest installment of his monthly "The Designer's Notebook" column.

I’m on an Internet mailing list that happens to include a lot of managers in the game industry. About every two years or so, a discussion flares up in which a whole bunch of the people on the list start complaining about employees who leave in the middle of a project, and what evil scum recruiters are for luring them away.

You know what? I’ve got no sympathy at all. I’ve been a manager, and I’ve also been a worker bee. I’ve seen this situation from both sides. If you don’t want employees to leave, there’s a simple solution: create a job environment in which they don’t want to leave.

Let’s look at some of the reasons that employees leave voluntarily.

They Think You’re a Jerk

If that’s the problem, it’s your fault, not theirs. Maybe you are a jerk. There are a heck of a lot of obnoxious managers in the world. Trouble is, most jerks either don’t know it or don’t care. If you’re not willing to change your behavior to keep your employees, then obviously your attitude is more important to you than having them on staff. As the manager, that decision is yours to make, but you’ve got no grounds for complaint if they leave.

You’re Working Them Too Hard

This reminds me of Robert Heinlein’s observation (expressed in his “Notebooks of Lazarus Long”) that no state has an inherent right to survive through the use of conscript troops and in the long run no state ever has. I would paraphrase that to say that no company has an inherent right to survive through the use of unpaid overtime. People will work extraordinarily hard for a company if the conditions are right. They’ll do it for one or more of four reasons.

The first three are: because they love the work itself; because they love the company or their co-workers; because the rewards justify the effort. If any of those three are true, you don’t have to worry so long as you maintain the conditions that engender that dedication, and you make sure they receive the rewards they expect. Fail to do so and you have only yourself to blame (you’re management, remember – it’s your company to screw up).

The fourth reason people will work extraordinarily hard is because they have no alternative: you’re demanding it of them, they have nowhere else to go, and they can’t afford to quit. Too many companies rely on that. If having nowhere else to go is the only reason overworked people are staying, then you can bet they’ll leave when the chance arises – and again, you’ll have nobody to blame but yourself.

Personal Reasons That Have Nothing To Do with You, the Work, or the Company

There’s nothing you can do here, and no point in complaining about it. If an employee needs to move to care for an elderly relative, or if he has decided to exchange the corporate world for life on a commune, the best you can do is wish him bon voyage. Any effort to keep him will only be temporary and you can be sure he won’t be as productive anyway. Negotiate a reasonable transition with goodwill and start looking for a replacement.

They Got a Better Offer Somewhere Else

Here you legitimately have something to be concerned about, especially if someone with a lot of money sets up an attractive new company in your area. For example, Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson is building a new studio, Wingnut Interactive, in New Zealand. The other studios in the area are undoubtedly looking hard at this: the talent pool in New Zealand isn’t that large yet and developers will probably feel that there is a lot of prestige to be had in working for Peter Jackson, and possibly more money as well.

However, just because your employees might get a better offer somewhere else doesn’t make them evil if they’re tempted by one. It’s called capitalism. Your employees are selling you a product, their labor. They only have a fixed amount to sell – unlike building widgets, they can’t increase their output and sell more of it to make more money. Their only option is to sell their labor for the highest price they can get, and if they can get a better price from another buyer, they’re perfectly entitled to do so. About all you can do here is to create the best-paid, most rewarding work environment you can, and let your employees know that if they’re thinking about leaving for more money, you’d like the opportunity to make them a counter-offer, and you won’t hold it against them for looking.

So what about loyalty? Well, free-market capitalism doesn’t assign much value to loyalty. Deliberately choosing to stay with you for sentimental reasons when there’s a better job elsewhere is irrational and therefore unquantifiable. Now, an employee who flits from company to company, always in search of a higher salary, is going to raise eyebrows; employers naturally want to hire somebody they can count on for a while. But employee loyalty is a privilege, not a right. It has to be earned by giving respect and good treatment. Any manager who expects an employee to feel loyal right from her first day on the job is a fool.

Furthermore, loyalty has to go both ways, and frankly, it seldom does. Companies want loyal employees who will stay with them through thick and thin, but those same companies want the freedom to lay people off on a moment’s notice when times get tough. Some of this is covered by labor legislation, of course: California, where I have spent most of my career, is a so-called “right-to-work” state in which either side can terminate an employment relationship without notice and for any reason or no reason at all. Other states have different rules, and Europe is another matter entirely, as many nations there have strongly pro-employee laws on the books. But the bottom line is that you don’t get employee loyalty by hoping for it or demanding it; you get it by building it, just as you do with customer loyalty.

Now let’s talk about recruiters. Recruiters are like lawyers – people say they hate them, right up until they need one. But when you need one, you want the best one you can get. Complaining about recruiters is hypocritical, unless you’re prepared to swear that you’ll never, ever use one – and any development company that makes that assertion must not expect to grow much. Big development teams always need recruiters at times. A team can rarely afford to take their time over hiring new staff, because when the project gets the green light, they usually need bodies on it ASAP. I’ve never yet seen a game job ad that said, “starting in three months’ time.” Unlike HR departments – whose primary role is managing the company’s relationship with existing personnel, not hiring – recruiters have the connections to supply those candidates quickly.

There are, of course, exceptions. A few large companies manage to get along without recruiters, if they’re farsighted enough to plan their growth well in advance. Some even have recruiters on staff. But most development houses don’t have that luxury; they literally don’t know until the deal is signed whether they need people or not, and they simply don’t have the network of contacts that a recruiter does.

It’s true that some recruiters use underhand tactics. Bad recruiters misrepresent potential candidates to their clients, saying the candidate is more qualified than he really is; they misrepresent the employer to the candidate, saying the job is perfect for him when it isn’t. A few recruiters also try to get hold of internal company phone lists, or cold-call people trolling for names while claiming to be employees inside the company. At one place I worked, a recruiter called around saying that he was in HR, and giving a 3-digit extension when asked for one. My company only had 4-digit extensions. In another case, a recruiter told me an employer was “very anxious” to meet me while at the same time telling them that I was “very anxious” to meet them. Neither was true; I went to the interview, the hiring manager and I had a nice chat about the early days of RPGs, and off I went.

There’s no question that this kind of behavior is sleazy… but it’s also a mark of desperation, and I’m convinced that it’s atypical. If a recruiter is to stay in business, she has to make placements, and she doesn’t see a dime until the candidate has been through the employer’s interview process. In the long run there’s no upside to sending inappropriate candidates along; it’s a waste of time, and pretty soon the employer won’t be hiring that recruiter any longer. Also, the industry is small enough that word will get around. Even companies that are in competition will warn each other off a bad recruiter.

The bottom line is that if there were no need for recruiters, they wouldn’t exist. They exist for a very good reason: finding qualified candidates is a long, tedious process and one that many HR departments aren’t equipped to handle when there’s a sudden demand for 35 highly-skilled, highly-specialized people in a wide variety of job roles.

The alternative is the way Hollywood does it: unions. A production company calls up the unions and says “I need fifteen carpenters and half a dozen electricians for the next six weeks.” The people work in short spurts, get paid staggering amounts of money for it during that period, and eat beans the rest of the time. They live by the clock, earning time-and-a-half and double overtime when their contract requires it. This is part of why movies cost so much to make – amounts that we in the game industry cannot possibly afford to pay.

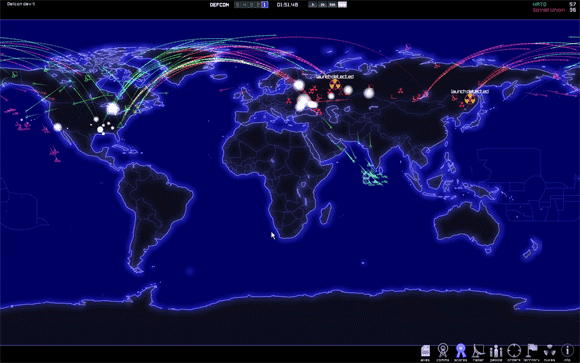

Trust me, unions are a direction we don’t want to go. Too much of game development has turned into a boring grind as it is, without adding union contracts and rules and strikes and all the rest of it to the mix. We’re here for fun and creativity; game development isn’t an assembly line. Also, unions and small-scale entrepreneurship, which is the game industry’s best hope for future innovation, don’t go well together. If every developer had to pay union scale, there would be no Introversion Software, no Darwinia or Defcon, no Independent Games Festival.

Although it sounds strange, most developers want and need the freedom to work for substandard wages when they have to… because most of us would rather be doing this, even for less money, than just about anything else. If the only jobs were high-paying ones, there would be a lot fewer of them around.

So don’t dismiss recruiters out of hand. They’re better than the alternative and they perform an important service that keeps the wheels of game development greased, moving people to where they are needed. And if that means some other company loses those employees’ services… well, that’s why it’s called competition. Employees leaving isn’t really that much different from customers leaving – in the end it’s all supply and demand, and whining about it, or trying to keep your employees in the dark, won’t help. Keep them happy and well-paid, and you’ll get that loyalty and productivity you want. It’s your company: deal with it.

Independent games such as Introversion's Defcon may cease to exist if game development switches to a Hollywood-inspired union model.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like