Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

The Audacity of Scope

"...judging by the last few major entries in the franchise, it would seem like the realities of the games business have finally caught up with the Japanese company that, for the longest time, seemed to almost never compromise on quality."

(Note: This post was originally written for http://odiousrepeater.wordpress.com. I'm reposting it here since earlier this week Nintendo announced their new WiiU Zelda game. I made some comments and predictions in the article below that should be evaluated in light of the new game's announcement. Indeed, Producer Eiji Aonuma made some comments about the traditional structure of Zelda games that pretty much acknowledge my observations about the design of earlier Zelda games. Maybe someone can translate the post for him and see if he can agree to the rest too.)

---

I’ve always loved the Zelda franchise. In so many ways I consider most entries in the series to represent absolute master classes of proper game design, and the Zelda formula has inspired not only the obvious homages like Darksiders, but also less immediately similar works like Resident Evil and Nintendo’s own Metroid (and by extension the so-called Metroidvania games from Konami). Though I haven’t played all of the Zeldas – especially some of the portable versions have eluded me – I’ve played enough of them to feel like I’m well-informed about the franchise and its evolution. Indeed, on some level I’ve always considered the quality of the Zelda games, alongside the high-profile Mario ones, to be a sort of measurement tool not only for the state of our industry, but even more so the state of Nintendo. And judging by the last few major entries in the franchise, it would seem like the realities of the games business have finally caught up with the Japanese company that, for the longest time, seemed to almost never compromise on quality.

Last year I read this article, filled with supposedly believable rumors about the next big WiiU Zelda game. Some choice quotes include:

“They got hundreds of people working on the new Wii U Zelda game”

“It’ll end up being the most expensive game they’ve made to date”

“…about the same amount of dungeons as previous Zelda games, but these will be vastly bigger in scope and will be totally different from each other”.

Some of this may end up being true. Indeed, maybe all of it is. Why not assume that the entire article is completely spot-on and prophetic at the same time (that is to say, that nothing will change during the course of the game’s development). That still leaves a lot of open questions about the production and marketability of this game.

It’s become an accepted fact even among non-developers that the costs of development are on the rise, and that they’ve indeed reached a point of vastly diminishing returns on many fronts (just this week or so, both Atari and THQ went more or less bye-bye). There’s a lot of nuance to consider here, though, which most people on the consumer side don’t know about. For example, there’s not really any correlation between the “size” of a game and how much it costs. There’s not really any correlation between play-time and cost either. The picture is a bit more complex than that. The absolutely simplest way to look at things, though it’s still not perfect, is to think about development costs in terms of manpower. Nothing ends up costing nearly as much on a game development project as the salaries of the staff, and the more ambitious the product, the more staff (and development time) are generally thrown at it.

Now, if your game is meant to make money, a good way to ensure a good return on investment is to establish what kind of features and content the game is meant to contain, and then to look at the best way to tick those boxes while keeping the manpower costs as low as possible. This is a bit tricky, of course. Let’s say your game is meant to last for 300 hours. That’s an easy box to tick for just one programmer; one can make a version of Pac Man that is so slow that getting to the end takes 300 hours – job done. Sadly, basically nobody would want to play that game, so there have to be more parameters added to the mix. Let’s say that the pacing is sped up so that the game appeals to everyone. That’s great, except that they now will be able to get through your 300 hours of content in just, say, 3 hours. So to balance that, you now have to add more reasons to keep playing, like new mechanics that keep the game fresh as you progress through the levels, new level layouts to stave off boredom and fatigue, multiplayer features, and so on. Of course, for each new parameter that is added, it becomes increasingly difficult to make the game happen without throwing massive amounts of money at it – thus increasing the likelihood that the project isn’t going to make its investment back. And to add some icing on the cake, the market has become increasingly sensitive to production values. While making a puzzle game may have meant great return-on-investment back in the days when Tetris was priced the same as Final Fantasy, those kinds of games are now expected to cost next to nothing to download to one’s mobile phone.

If it’s not already obvious how this all connects to the Zelda franchise, and the future WiiU Zelda, let me spell it out: the classic Zelda formula is horribly unforgiving and inflexible from a production standpoint. Many would argue that A Link to the Past for the SNES is the benchmark gold standard of the franchise, so let’s look at what Nintendo chose to put in the game when cost was much less of an issue than it is today. A Link to the Past features a massive amount of play time, beautiful pacing, very little repetition (granted, this is subjective), two separate interlinked overworlds, masses of different enemies, unique events, bosses everywhere and very, very little collection/fetch-questing. If we were to draw a line between this game and the latest one, Skyward Sword, we can more or less see how with each new Zelda, Nintendo have tried to stick as close as possible to the Zelda experience, while at the same time keeping the relative development costs as low as possible.

Skyward Sword's map; a bit on the barren side, but quite flexible on the other hand

Skyward Sword's map; a bit on the barren side, but quite flexible on the other hand

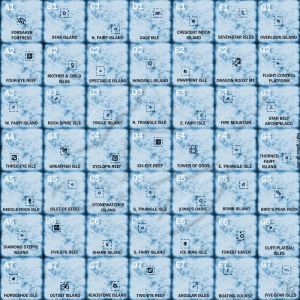

Let’s start by looking at the handling of level design in the Zelda games. Since the SNES game there has been a marked increase in fetch/collection quests and time spent traversing the surface of the game world. Furthermore, the overworlds in many Zelda games have become increasingly modular – The Wind Waker and Skyward Sword should immediately spring to mind. The reason for both of these changes is that Nintendo are trying to get as much play time out of their overworlds as possible, while at the same time being more flexible in pacing and content structure. The Wind Waker had the player sailing from island to island. Skyward Sword had the player flying between islands that were suspended in the sky, or through portals to the world below the clouds. Both setups allow the development team the luxury to simply add to or cut scope from the overworld without it being quite so obvious. If, on the other hand, they would have insisted on carving out a static piece of land for the overworld’s creation, that land mass would have to be painfully redesigned as the scope of the game changed throughout production, or risk feeling very barren (I’m looking at you, Twilight Princess). It could in theory also have ended up too packed with stuff on too small a surface, but that’s very unlikely – people usually underestimate workload, rather than overestimate. Additionally, Skyward Sword feels absolutely no shame in repeatedly using its dungeons and/or the surrounding areas for new purposes as the player progresses through the game. While I’m not averse to revisiting old areas in principle, in the case of Zelda this is quite obviously a cost-cutting exercise – especially when it’s mandatory and not simply about finding secret treasures or other optional content. Adding new game logic and scripting is much, much cheaper than creating totally new areas, so that’s what Nintendo have chosen to do. Not a bad idea – but less close to the Zelda formula established in A Link to the Past than they themselves would have liked, I’m sure.

They didn't even try to hide how modular the map was in The Wind Waker

They didn't even try to hide how modular the map was in The Wind Waker

Another part of the formula where Nintendo have been cutting back is the area of enemies. Skyward Sword especially was a great example of highly MMO-influenced content design, with base enemies being reused in various forms, sporting slight differences in aesthetics and functionality. It’s, again, understandable; once you’ve created a combat system as comparatively advanced as the one in this game you’ll want to be able to reuse it as much as possible. Tweak a few hitpoints of the Moblin and/or give him an electrified sword and bam – a “new” enemy derived from the first, very pricey, one.

We're different from each other, and that other guy too!

We're different from each other, and that other guy too!

I'm nothing like those other guys!

I'm nothing like those other guys!

And then there are the bosses, which are notorious for being one of the most expensive types of content to make in most games, and perhaps especially in these types of games. It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone that The Wind Waker had the player fight the same bosses again towards the end of the game, while Skyward Sword had a very small number that they recycled much in the same way as the normal enemies.

Hey! Think you can beat me? Like... 4 times?

Hey! Think you can beat me? Like... 4 times?

Finally there’s the whole upgrade system, which is very MMO-like in its nature, what with the tiered resources and collecting involved. On top of that, there are plenty of money sinks in the game, and a clear scarcity of cash, which slows the pacing down quite a bit for those who want to power Link up to the max.

All of these design decisions are direct consequences of the financial realities of maintaining the Zelda formula. We can argue the benefits of collection quests and grinding, but just by looking at how Nintendo’s worked in the past I feel confident in assuming that they would rather have their games contain every single feature idea they could come up with, and have all the content be as contextually appropriate and unique as possible. But that’s simply just not feasible as the cost of content is increasing. And although the kinds of sales figures that Nintendo have been seeing from the Zelda franchise have consistently been high, absolute numbers don’t count for nearly as much as relative numbers. If throwing twice as much money on a game doesn’t earn you twice as much back, you’ve generally made a suboptimal investment.

So even if this work-in-progress HD Zelda game does end up being the most massive endeavor in Nintendo’s history, even if it is unparalleled in size, scope and outright quality, then it will end up being a major departure from where this franchise has been going lately, and will more likely than not represent a relative dollar-for-dollar loss for Nintendo. The only reason I could imagine the Japanese giant making a prohibitively expensive game like that, considering the very prudent design and production methodologies they’ve used lately, is that they simply want to get more WiiU consoles into people’s homes, even if they have to do so at a relative loss. While that would of course be a somewhat good thing, it would still be less than ideal, and just this week they announced that they would be re-releasing The Wind Waker on WiiU – to hold fans over while waiting for the newer Zelda. Who wants to bet that whatever engine ends up powering the WiiU version of Wind Waker will be derived from the one they’re developing from the newer game?

Early footage of the HD version of The Wind Waker

Early footage of the HD version of The Wind Waker

Finally, though this post focuses on Nintendo, it’s not really meant to comment on them so much as to use them as an example of the relationship between market realities and game design. If we keep these same return-on-investment-goggles firmly attached to our faces and gaze elsewhere, we’ll see that other Nintendo games are also fighting the battle between scope and cost. The Super Mario Galaxy games, for example, are very modular in their design, and much of the content of Galaxy 2 was no doubt conceived for the first game. Far be it from me to pretend to know what Nintendo is thinking, but I smell a time-to-market mentality, which used to be all but unheard-of among Nintendo games. As for the rest of the industry, they have been padding their games much less gracefully than Nintendo for even longer. There is experience point grinding and similar sorts of systemic content in genres that historically never featured such things, and the entire Achievement system that so many platforms and games use is (among other things) a way of artificially squeezing more playtime out of the same amount of content.

Is all of this, then, a bad thing? No, not in any absolute, general sense, I think. What it is, though, is a confirmation of how we, the consumers I mean, are still regarded as children, at least as far as our spending patterns are concerned. A friend of mine quite eloquently said that when you’re a kid, you have no money, but you have plenty of time and energy. As you get older, you get less time, though you now have money and energy. When you’re older still, you have money and time, but less energy. The industry’s desire to pump out gaming experiences that above all feature tens of hours of gameplay, caters to those of us who think that entertainment-hours-per-dollar, is more important than the quality and variety of said entertainment. I would personally quite gladly play a shorter Zelda that’s constantly pulling new tricks out of its hat, and never compromises on pacing or the quality of its content, but that just doesn’t seem part of the formula, and I’m not sure Nintendo would ever risk toying with it. What if the kids started thinking that Zelda games were a bad investment?

It’s a bit of a shame. Not because I’m so naïve as to think that a formula conceived and perfected in the business and development environment of 20 years ago would ever be able to scale with all the changes our industry has seen over the years. No, I just wish the formula would have grown up alongside us, and that instead of desperately padding their content, Nintendo would simply accept quality and variety as the baselines of the franchise, rather than trying to make sure the games feature a set number of hours of playtime. Because when it’s all said and done, the water cooler conversations and rave reviews that Zelda games have elicited through the years have always been about quality dungeon design, clever puzzles, awesome boss fights and other similar highlights.

Nobody remembers the time stamps on their save files.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like