Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

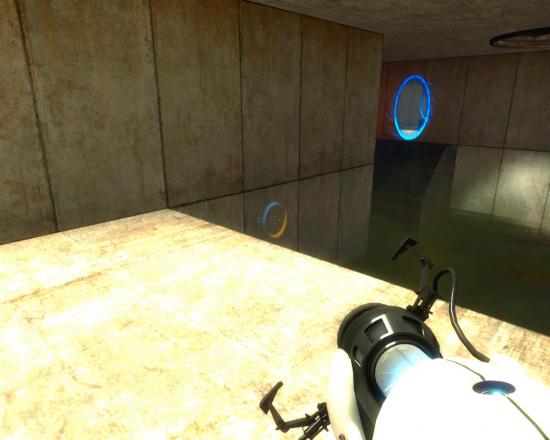

Kim Swift and Erik Wolpaw are the lead designer and lead writer of Valve's Portal, a game you may have heard of - and in this Gamasutra interview, they go into detail on the game's creation, director's commentary, and, uh, 'time to crate'.

Portal is one of the most charming success stories of 2007. The game's creativity and heart is matched by its high quality -- and that's all backed by a romantic story of a bunch of students improbably scooped up and allowed to let their vision blossom at a top-tier studio.

At GDC, Gamasutra had a chance to speak to Kim Swift and Erik Wolpaw, the game's lead designer and lead writer, shortly after the game won three major Game Developers Choice Awards - including Best Game Design, Innovation, and Game Of The Year.

Over the course of the conversation, the topics of how its unique narrative-linked design came about, the strengths of working at Valve, and even the possibility of Portal DS were discussed.

How do you feel after the awards? Did you expect that you were going to get that many?

Kim Swift: No, we definitely did not. We're pretty damn happy, I'd say.

Erik Wolpaw: Yeah, it's been kind of shocking. It's a shock. I don't think anybody really expects that they're going to win something like that.

KS: And the fact that it's game developers who are doing the voting and making the choice for the awards makes it all the more significant.

I thought it was interesting that a lot of the games in the innovation and downloadable categories were previous IGF or student showcase titles. Did you notice that?

KS: Yeah, I did. That's pretty cool. Being in a similar position, having Narbacular Drop become Portal... it's a wonderful thing to see, with people trying new things and being successful, and being able to put their ideas out there and accepted.

About your process... I was really impressed with the way that the narrative and the game design was well implemented. I'm wondering how you came to that.

KS: Well, we had a half an hour speech about that. (laughs)

EW: It was one of our goals. It was a goal that we had, to tightly integrate the gameplay and the story together, but it would be actually easier to do that in some ways because of all the constraints we were under. We were a small team, and we have all the resources at Valve at our disposal.

That helped, but a lot of people were busy releasing three products at once. Some of that was planned, and some of that was a way to creatively sidestep the restraints we had.

KS: A lot of it came out of the fact that we playtested our game every single week. We were watching people play the game and seeing how they reacted to certain situations, and tried to play up how they were feeling at the time with the dialogue and different turning points in the story. We definitely had our players and our customers in mind when we were making the game.

What really impressed me specifically about the story was the way that the two were really one and the same, kind of. There was no exposition, really. The way that you found out about the world was by things that were there. I was wondering if that was design-driven or writer-driven, or was it a combination of the two?

KS: I'd say a little from column A and a little from column B.

EW: The combination of the two. It goes back to the playtesting again. The playtesting helps test the gameplay, but at the end of the playtest, we'd also ask people to tell us the story back. "Tell us everything that you remember about the story."

If enough people weren't picking up on things, generally speaking, it was an indication to us that they just didn't care about it, which meant we should probably either cut it or in some cases where we didn't really want to let it go...

KS: Make it better.

EW: Well, it served us better usually to cut it. We generally found that if we added more of it, people just tuned out more. Usually, if they weren't interested enough to pay attention to it, it was better just to cut it. Although sometimes we would try and move it into the environment itself. In other words, instead of having somebody talk about it, or GLaDOS say something, we could just maybe offload it into the environment somewhere.

When I first got behind the world... up until the point, I was just playing the game, and then when that was there, it was like, "Oh, there's definitely a lot more here." Obviously in the game design, but also in terms of the emotions felt, it felt like things were revealed very carefully in a sophisticated way. I've been telling people that I feel like Portal is one of the more sophisticated narrative-driven games, even though it's hard to call it that, really, because it's just actually well-realized.

KS: Thank you! (laughs)

EW: That's a nice thing to say.

KS: It definitely has a lot to do with process and the fact that we sat down to watch people play our game. It's really incredible, how much information you can get just from watching someone play your game that hasn't played it before.

Seeing what they think about the game and watching the expressions on their face, you can tell if they're happy with what they're feeling, or if they're bored or if they're sad. We were always very deliberately watching our players to see how we could make the experience better for them.

It struck me. Obviously we had the postmortem in the magazine. I was wondering -- why don't other people do it this way? I mean, I'm sure other people can't afford to take the time that you're afforded by being with Valve, but that kind of collaborative, iterative process that intertwines every element seems like a good way to go, but a lot of people seem to do every part of the game separately and then merging.

KS: To be perfectly honest, I think it would save people time. Like I said, you know if the player's unhappy, so if you think you've got a really great idea for some piece of exposition or gameplay, the faster you get it in the game and start exposing it to people, the faster you realize whether it was a good idea or a bad idea, and whether you should abandon it as soon as possible or keep improving.

EW: I'm just speculating, but there's a psychological component to it. Valve's, for lack of a better term, corporate culture is "Playtest, playtest, playtest." Portal was being playtested in the first week. But when you're working on some sort of creative project, your natural inclination is to not want to show anyone until it's in a state that you think you can be proud of.

But at Valve, we're putting you out there, and you're going to fall, fail, fail. You'll have little successes and little failures, and until you get used to the process, it's a little bit scary and painful. But it's really worth it.

KS: Yeah, we definitely start by showing players very unpolished stuff. For instance, in the levels, once we all sit down together and decide what a level's going to look like, we try to build it as fast as possible, and in two to five days we'll have it up and running.

We'll get someone to go through it for the first time, and you know, they're not pretty looking. They'll definitely need a lot of polish and care before we're ready to ship, but the sooner you start getting player feedback, the better off you're going to be.

How difficult was it adjusting to that process?

KS: Not hard at all. It was actually something... when we were working on Narbacular Drop, we wish we had known that that was actually a good idea. When we were working on Narbacular Drop, we playtested the game a few times, maybe a month before it was due.

We came up with a lot of things we didn't fix, and we just didn't have time to fix them. The sooner you start getting people to really know your games and start playing around with it, the sooner you'll find all those problems that because you're exposed to the game every day, you're not going to see them.

Do you think it was easier to adjust to it because you came straight out of school? I was just wondering that, because it seems like someone who was entrenched in, "All right, I'm going to wait until it's nice to show it to people," might have a hard time.

KS: I don't know if it necessarily made it easier for us to adjust to it. From our standpoint, we want to make the best player experience we possibly can. This seemed to work really, really well for us to figure out what we've done right, and what we've done wrong. It keeps you really objective, too, which is great.

When the writing and design was happening, did you intend to do something new?

EW: No, it wasn't like, "want to do something new." We knew the mechanic was going to be pushed. Even though the portal concept was sort of out there, even in -- I hate to say it -- Prey or whatever, there were games that had it, but we knew that we were going to push it as far as we'd think we could push it, and really focus on that particular mechanic.

In terms of the writing, the only thing was that -- and I wasn't sure if we were going to pull it off -- I kind of wanted the player to not have this nemesis that you eventually meet and then destroy.

I wanted you to actually see you progressively breaking the evil villain character down, and actually give you what I thought would be the satisfying experience of seeing your actions really cause the villain some emotional pain. And we wanted it to be funny, too, so that was a goal.

KS: There's something inherently kind of humorous in playing around with portals and bouncing through these objects. The fact that Erik is really great at writing humor... I think it just played really well together.

I don't know if it was intentional, but obviously GLaDOS is also a sympathetic character. It's like, you're breaking her heart, but she was fun, you know?

EW: Yeah.

KS: She still loves you! (laughs)

It is very strange to say, but it had more emotional impact than some other things that really try to be epic and sweeping, and narratives that are all about revenge and you have to kill someone because they killed your father.

EW: Yeah. It's always more satisfying for me, personally, when I feel like I can sort of understand the villain in a book or movie and empathize with them a bit. It makes their villainy a lot more tragic.

KS: And human.

EW: And human, yeah. That was the one big rule for writing GLaDOS -- just write her as if she was a person going through a robot "oh my nuts and bolts" sort of thing.

KS: What was nice about the progression was that she got more and more human toward the end of the game.

EW: Yeah, we wanted her to keep getting more and more human until by the end, when the morality core comes off, [voice-over actress] Ellen [McLain] switched to a different voice.

KS: She's our voice actress.

EW: The other thing was we loved Ellen so much and we did a lot of recording with her, so that helped evolve GLaDOS. It was like, "Oh man, I don't want Ellen to say this. Ellen is super-likeable. We should write for that."

It's something you don't always get in games. Because we only have one big character in the game and one big speaking part... a lot of games, you go in with the voice actors, and you have one session with them.

You don't get to do a lot of prep work, so you just do the best you can. But with GLaDOS, over the development cycle, we were actually able to write to the strengths of the actor, which is something you don't always have in the game world.

I would say you usually don't have it.

EW: Yeah.

You may not have been directly attempting to advance narrative and gameplay integration, but I think that's what happened. I would call BioShock and Portal the two games that have pushed it forward by at least trying something that's different. Portal isn't exactly interactive narrative, per se, but it feels like it. Even though the narrative is on rails, the things that you do, she'll still comment on them, like when you knock down the security cameras or things like that. It gives you the feeling like you're affecting it.

EW: We hoped to do that. We had this theory that games tell two stories. There's the "story story" which is the cutscenes and the dialogue, and the "gameplay story" which is the story that's described by the actions you take in the game world. The theory was that the closer you could bring those two stories together, the more satisfying the game would be.

I spent years and years reviewing games, and that's something that always bothered me in games, where the delta between the two stories was real high. I promised myself someday that if I ever got the chance, I'd try to make a game where that delta was almost zero. It was a conscious decision that we wanted to try and keep that world.

KS: It takes you out of the experience, really. You're doing one thing, then all of a sudden the story is telling you, "No, no. You actually did this other thing." "But no, I just did the... all right, fine. You're right, then." I agree with Erik that the closer the gameplay interacts with the story, the more impact it has with players.

Just as an aside, I found it humorous that you're carrying cubes around a lot and it may have had quite a quick "time-to-crate."

EW: Yeah. The crates were in there before I started, so we just tried to make the best of it. It was like, if we were going to have to have crates, they would be the best crates ever.

KS: I guess it would be like a minute and five seconds, in time-to-crate. We trap you in that first room for a minute! (laughs)

EW: It's relatively long. There's an artificial trapping, so we could boost that time-to-crate up. We just call them cubes, though. We never call them crates. It was kind of saddled with it. But then again, it was another constraint, and we tried to make the best of it.

It worked well. You got to destroy the dearest one.

EW: Yeah. It worked out okay in the end.

I had the impression that one of the overarching themes was simplicity, like keeping everything not bare-minimum, but to the essentials, so it never felt superfluous. There was nothing around that really wasn't necessary. Was that something you were going for?

EW: It comes out of playtesting, again. It was the rule we had -- that if enough playtesters couldn't tell us what was going on, it was just too complicated. It wasn't them. It was us. It's our fault that we weren't delivering...

KS: ...entertainment.

EW: Yeah, we're not entertaining. If somebody isn't interested enough to pay attention, then it's definitely not entertaining.

KS: I think there's something to be said for letting players fill in the gaps for what they think they're experiencing, as well. It makes it a lot more fun to have someone dictate to you exactly what the story is going to amount to.

I agree. It gives players credit for having brains, which games often don't do. They're like, "And now you will do this! This thing happened, and here's the backstory." But in this case, I hadn't even really played Half-Life that much, so it still worked for me, without knowing who Aperture Science was.

One thing that I liked, and I don't know if this is intentional, since I didn't listen to all the commentary, was that in the first room, or really early on, you can see the offices. And when I saw that, I was like, "Man, I'd like to get up there." And then at the end, I'm looking out of there.

KS: Yeah, that was totally intentional. Going back to playtest again, we always had comments from players like, "I want to go in that room!" So towards the end of the game when you finally break out, we were like, "All right, we're going to let players see those rooms now." It was definitely fun for us to give that to our players.

Would you say that the design is more designer-driven or playtest-driven? Or is it kind of the same thing?

KS: I think it's one and the same, honestly. It's going back to trying to make the best player experience that you possibly can. At some point, there needs to be inspiration for you to get started and put your ideas out there, but like I said, it's just really, really healthy to stay objective and watch your game be played, because then you'll know if your ideas were good or not.

EW: I totally agree.

What about the lack of speech for the protagonist? Was that completely intentional, or was that just a byproduct of this?

KS: We wanted to keep the Half-Life 2...

EW: Yeah, once we were going to tie it into the Half-Life universe, one of the conventions of the Half-Life games is that the lead character doesn't talk. But the general atmosphere of Portal made it so that it sort of made sense. The main character wouldn't ever need to say anything.

KS: Unless she wanted to talk to herself.

EW: Yeah, she'd be more or less talking to herself. It was a conscious decision, but we made that early on, and it was never anything that we agonized over too much.

I was expecting her to either start talking to herself or have hallucinations about the companion cube talking to her, or something, because there kept being references to it.

EW: That was a debate we had. At some point, we'd had the companion cube saying something, but eventually, we just decided that it was stronger that it was hinted at, and it never actually said anything.

KS: Though you do see it at the very last FMV sequence at the end of the game. There is a companion cube.

EW: Yeah, he's there. Silent.

Do you think this kind of level of narrative could be achieved with a protagonist that speaks? Is it possible for the player to relate to that character?

KS: I have no opinion.

EW: I think it could. The less simple you make it, the more you risk increasing that delta between two stories, which is a harder problem. We optimized for keeping that delta low, and one of the ways we did it was by keeping the protagonist silent.

That was the only thing where I was like, "I wonder what would happen if they tried this?" It was already advancing things, so I was wishing that you could figure out how to do that, too.

EW: It may very well have worked, but like we said, it was one of the things we decided on early on, and we never saw any need to worry about it.

I didn't mean necessarily for Portal.

KS: I don't see why not.

EW: Oh yeah, you could make it work. I can't imagine why you couldn't. I'm trying now to think of a game with a non-silent protagonist that works really well.

That's the thing.

EW: For shooters -- Portal's got that shooter viewpoint -- I tend to prefer games where I don't...the main character isn't speaking. Part of it is just a practical thing.

KS: It's distracting.

EW: Well, it's distracting, but also because I can't see the character, sometimes it's confusing to me who's talking.

KS: Yeah. "Was that a dude over there, or was that my character?"

EW: In Portal maybe it wouldn't have been as big of a deal.

KS: There aren't any other characters.

EW: But still, who knows.

Did you play King Kong? It's actually pretty good.

EW: No. But I did play the demo.

You should play it. It's all right. It's a good realization of what, in my opinion, all those Sega CD FMV people were trying to do back in the day with movies.

EW: So is it first-person?

It's first-person, and he talks sometimes. You can tell just because of the way they do the sound phasing and stuff. It sounds like it's coming from here, whereas all the other characters sound like they're coming from over there.

KS: Interesting.

EW: You could definitely make a game where you do that. The Half-Life games, and Portal especially, again, the main character is just a player surrogate. It's sort of a cipher. It's a complete blank slate you impose your own viewpoint on.

The two hour total playtime, was that a target, or was that just a result of how much you felt you wanted to put in?

KS: It was pretty organic. We didn't really have, "Oh, we need to hit two or four hours." The length of the game mainly came out of our playtesting. Actually, the ironic thing was that the better we tuned our game, the shorter the game got. (laughs)

It was kind of sad for a little bit, but it gave us enough time to give us a good story arc and get to know GLaDOS, and weave the game with a sense of accomplishment and learn this new tool. We thought it was a good stopping point.

How has the reaction been to the length, from your perspective? I thought it was good.

KS: We get mixed reactions. Some people are like, "Oh my god, what are you doing?" and other people are pretty appreciative, especially in the game industry, I think.

EW: Yeah, or in adults. They're constantly referring at Valve to people who really think a lot about games and play games, and many of my adult friends never, ever finish games anymore. Like, they don't finish them. We just thought it would be nice to have a game where, if you play it, you probably will finish it, unless you just don't like it.

In direct opposition to your mixed feelings about how people are reacting, I'm surprised at just how positive the reaction has been, or what a non-issue, in a lot of cases, it's been. At two hours, I think a lot of players are more dedicated to it. In Steam stats, it's more like three and a half. Regardless, though, it's still short.

Although it seems to be a trend. In Call of Duty 4, the single-player is awesome, but I think it took me five and a half hours or something. So it's not super-long either. That seems to be the trend. BioShock was pretty long, but it almost seems like a throwback, in how long it was.

Yeah. I have finished Portal and Call of Duty 4, but not BioShock, even though BioShock is awesome.

EW: That's the thing. There's a practical constraint on time for people who aren't 14 years old. You just can't spend that much time playing a game, so is it a good thing to have games that people eventually just get sick of before the end, or run out of time? A lot of games I would like to come back to, but there's this barrier of reentry, in which I don't remember what the hell I was doing a month ago.

I'm wondering how you would... I heard the possibility of expansion or something like that. How could you keep going in the Portal world?

EW: There's other avenues to explore. We haven't announced anything yet. We're definitely thinking about what comes next, but we can't really talk about it at this point.

Okay. Well, I'm not trying to get secrets out of you.

EW: That's all right. It's your job.

Well, not necessarily. I'm just trying to think... since GLaDOS is dead and stuff.

KS: Well, the title of the song is "Still Alive."

EW: Yeah, she might still be alive.

That's true. So it's something you actually want to revisit, instead of something different?

EW: We like the world of Aperture Science, and we'd like to revisit the world of Aperture Science in some form, whether it's GLaDOS or Chell or something else. But Aperture Science seems like a rich environment for this game to take place in.

Do you have any plans or hopes to do something beyond, or other than, that?

KS: You mean like work on other games at some point? Well, obviously. There's only so many sequels we can make.

EW: The good thing at Valve is that everybody's got their hand in different things. I don't know how many projects Valve has going on right now, but it's a fair amount. You can bounce around and help out here and there, which helps alleviate the grind you get into of doing one thing over and over again. You can spread yourself out a little bit.

Since the process is different... someone made a comment at DICE a little while ago that all of the biggest blockbusters of this year, and in fact through the 2000s, were delayed or took a long time. Do you agree? What do you think that says about what people are doing?

KS: I think that means that they care about their players, right? You don't want to send something out the door that you don't have faith and confidence in. It's not a great thing to do.

EW: Before I worked in the game industry, I was a database application programmer. It was exactly the same thing. No project that we ever worked on shipped on time, so it may just be a software thing. I know there's lots of theories about it.

Movies seem to come out and be produced more or less on time. When a movie is delayed significantly, it's big news. I think it may be a software thing, and something to do with software.

Games do come out of that, it's just that those aren't the ones that are awesome a lot of the time.

EW: Putting extra time into something... I was going to say "makes it better," but that isn't actually true either.

KS: Well, it's more like, "making sure that you're ready."

EW: Did Call of Duty 4 come out on time? Was that delayed? When people don't announce dates, it's hard to tell.

I think that was probably Call of Duty 3, originally, but Activision was like, "We need a Call of Duty right now."

EW: So what we need to do is less of that. "We're not coming out until we're ready."

I think they do that for investors. With the movie example, it's because there's a much more established process, and in games, everyone's doing stuff in their own way, and the tools aren't integrated or the same across the board. There's so much noise that has to be clipped out first.

EW: I think so, yeah. All those factor into it. But again, it's like the database applications. Nobody seemed to be able to deliver those on time. I don't have smart ideas about it, except that...

KS: To not announce it until the last minute?

EW: It's endemic in any software undertaking. There's something about writing software that causes delays.

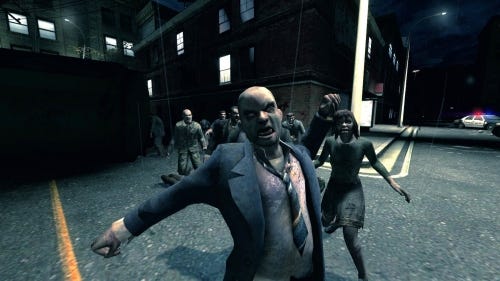

Turtle Rock and Valve's upcoming zombie-focused co-op FPS Left 4 Dead

I'm curious to know -- this is also tangential -- how did Mike Patton get involved with Portal?

EW: He does the zombie noises for Left 4 Dead, and he had recorded like a two-and-a-half minute demo for us. It wasn't like we were auditioning him. We just wanted to know what he would sound like. We had Ellen originally do the anger sphere, but she was just too nice, and couldn't quite pull it off.

I was panicking at the last minute, and just happened to be doing some of the Left 4 Dead stuff, listening to the Mike Patton voice, and I was like, "Oh, we should use this!" So then we had to go through a little bit of union stuff, and we were eventually able to buy it and put it into the game. I don't think he even knows.

KS: Yeah, he knows.

EW: Does he? Okay.

He probably played it.

EW: I don't know about that.

Really? He does play games.

EW: He may have played it, then.

With Mr. Bungle, he used to do Super Mario Bros. stuff.

EW: Oh wow. He may have actually played it then. He was excited about Left 4 Dead.

I think that's why he's doing more voice acting now. He's the protagonist in Bionic Commando.

EW: Oh, that's right. He's got a good voice. If you need somebody to make monster sounds, he should be your go-to guy. He's just a savant at that stuff.

Not that you would ever do it, because it's not really Valve's MO, but do you think Portal could work on a handheld, like on the DS?

KS: That could be cool.

EW: Somebody made a Flash game that was pretty clever 2D implementation of it. Yeah, I think it could. I'd love to attempt a DS version, but I don't even know what the process would be to get that going. I guess we could ask Gabe. I think it would be neat. People would like that on the DS.

KS: I know I use my DS all the time.

I'm pretty sure that Source is not running on the DS right now.

EW: No. I don't think I'm giving anything away by saying that it is not.

What do you think about -- and I know this is a business-y question -- download versus retail-type stuff right now? Obviously Portal came out for both. I played it on my 360, but I don't know if people played it more on one than the other, or which you think is the better delivery platform.

KS: I think to each their own. Me personally, if I'm buying a game on the PC, I want to download it through a service like Steam. It just makes my life easier. If I'm sitting around one afternoon and I'm like, "Oh, I'd like to play such-and-such game," I can just go and download it real quick, as opposed to, "Oh, I've got to get dressed and go to the store." It's nice.

EW: From a business standpoint, I'm not sure which is better, but personally, I just want to download games, and not have any box or physical media that I have to store somewhere.

I've been complaining recently about the retail market and how all publishers and developers by extension seem to be afraid of GameStop and kind of kowtow to them and let them make decisions, when they're making way more money off of games than anyone in the industry.

EW: I'm not even aware of the...

The used game market.

EW: Oh, the used game market.

Yeah. They're the only people who make money on that thing. It was like the plurality -- not the majority -- of their business this year.

EW: Really? I didn't know that.

Oh yeah. There's some graphs and stats out there.

EW: Because I've never bought a used game from GameStop, because they're always four dollars less than the full-priced game. I'd buy one off of eBay or something.

KS: I'd buy them if they were significantly less.

EW: Well, someday. Like 20 years later you can get a Super Nintendo game for five bucks or something, but usually used game-wise, I just go through eBay. But that's interesting to know, that they're making so much money now on used games.

You have a good job, is the thing. A lot of people don't, so that four dollars is like, "Oh, why would I get the one that's four dollars more?" When it's a difference of four dollars, GameStop is making like forty percent more.

EW: That seems like a big markup. My big thing with new versus used was whenever I'd go into GameStop, it always surprises me that the used prices aren't significantly less than they are. Although it's one of those things... it's also the prejudice that I have of "it's used." But with games, it really isn't any different if it's used.

KS: Well, I guess it could be scratched or something.

EW: But that's the difference between working and not working. I guess just to make GameStop case, it's not like used underpants or something. It's just as good.

KS: (laughs) That was non-sequitur.

EW: Well, you wouldn't want used underpants or gently-worn underpants.

If you washed them?

EW: Yeah. That's why I do buy games from GameStop. It's convenient.

So how did you get involved with Valve? How long have you been there?

EW: A little bit more than three years now. I had worked at Double Fine, then I left Double Fine, and moved back east, and I was just doing freelance writing. Honestly, it was just like one day I got an e-mail from Gabe saying, would I want to come down to work at Valve? So I came down and talked with him.

It seems like they do a fair bit of outreach and looking around for people. Is that your perception?

KS: Well, yeah. The fact that the team, obviously with the exception of Wolpaw, were assembled not that long ago, and they picked us up at a job fair. There was a general...

Valve is always looking at the modding community to see the new and interesting ideas people are making. The Counter-Strike guys came out of the modding community, and the Team Fortress guys with Day of Defeat. It's all people in the modding community.

A lot of people talk about how it would be great if you could hand-pick the people to work on a specific game, like you do in the film industry. Like, "I want to get Steven Spielberg to direct, and so-and-so to star." It seems like maybe Valve is almost trying to do that, by not necessarily finding established people, but finding new people that are good.

EW: Except once you get there, then you stay. It's not like teams come together and then break apart again after the project. It's somewhere in the middle. Valve does aggressively recruit. I think game companies in general do that a lot, but Valve seems to generally be more aggressive about it. People talk in Valve a lot about who's out there and who we should hire and who we want to work with.

Do the teams generally stay as they are, or is there flow between them?

KS: They usually shuffle around right after a project ships. People want to go do something else for a little while, and some people want to try something new. There definitely is an ebb and flow to things.

EW: Yeah. Generally, you work on what you're interested in working on, and by the end of the project, a lot of times, everybody comes together. We pull people in at the very end -- some of the super-high level artists give us an art pass through Portal. There's always people jumping on at the end, but yeah, people sort of shuffle around and work on what they're interested in.

How did the idea for the developer's commentary come about?

KS: Well, that was something that was done in Lost Coast.

EW: I don't know who thought it up, but Gabe maybe decided to put it in there. It was popular in Lost Coast, so we've done it in every product since then. I'm assuming it will just keep going.

KS: Yeah, we've gotten lots of positive feedback about putting in developer commentary, so I can't imagine we'd stop.

EW: Yeah, I don't think we're going to stop. Hopefully it'll get better. There's a lot of features we'd like to add, sort of interactive visual displays and stuff that'll actually show you what levels looked like earlier.

Concept art and things?

EW: Yeah.

I think it's pretty good, not just as something for people who are interested, but similar to director's commentary for movies, kind of. Have you gotten any feedback from aspiring developers?

KS: Yeah, we've gotten a few e-mails from people saying that the process was really interesting and they learned quite a few things.

EW: Yeah, and one of the goals of it is that even though it's commentary, to try and make it a little bit focused. Instead of having four of us sit in a room and ramble about what we think about the game, we try and actually make each little commentary node have something to say -- something interesting or some point to make about the game or the design.

KS: It's actually quite a good postmortem for us, too, where we can sit around and try and reminisce about "Well, I've worked in this area."

EW: Well, it's not actually a postmortem, because it's coming together in the crazy last four weeks before we ship.

KS: Well, we do have to think about it, though. (laughs)

It's maybe an end-mortem. The only design weirdness -- and I don't know if it's design or implementation or what -- that I found was whenever I would die in the water, I wouldn't know what was going on. Sometimes the portal gun would be lying there, and I could look around and stuff, but I couldn't move and wasn't quite dead yet.

KS: Yeah, part of that came about because... we used to have ragdolls, so whenever you would die, your player would ragdoll, so you could obviously tell you were dead.

It's something we took out of the game at the last minute, because our ragdoll wasn't acting properly, and would pose in odd positions and made us uncomfortable, so we took it out, because we didn't like how it was looking. We didn't get a chance to put in a really good signifier that you were dead.

Also, I didn't know what I could do, because I had some movement ability still.

KS: Well, we wanted you to be able to look around while you were dead, to see what killed you. In some cases, the fact that you've got a free mouselook bound to where your corpse is really nice, especially if you got hit by an energy ball. We tried to focus the camera a bit on the energy ball, and it didn't work out so well.

It took me a while to realize I had to do something if I wanted to be alive again, unless I wanted to wait more.

KS: That's actually a Half-Life convention, that you have to click or press a key to come forward. It's something we had too.

That was something I should've known already!

EW: No, again, it's playtesting. We failed you.

KS: It's our fault. (laughs)

I wanted to ask what other games you found good or interesting, either from a design or writing standpoint in recent times.

KS: It's been awhile, but Katamari Damacy I thought was a really, really interesting design. Portal sort of has a similar feel to it. We've got one game mechanic, and one way of interacting with the world. You just get practice at it and get more and more abilities as time progresses with the one game mechanic.

EW: Writing? Well, no. Plus, I'm totally obsessed over the last week with Patapon. Have you played that?

I have not.

EW: It's for PSP. It's amazing.

KS: It's fun to watch you play, actually.

EW: It's incredibly charming, and it's a super-clever hybrid of a rhythm game and an RPG and a strategy game. I can't stop thinking about it.

KS: And the art style is really cool.

EW: Yeah, the art style is really neat, and it just all completely works together in this little package. It's cute, but really, really deep. That's my big game of the moment.

I'll definitely play it. I've been looking at it and thinking about it.

EW: You should make the plunge, because it's awesome.

KS: I'm actually considering buying a PSP because of the game.

I do own a PSP. I don't own a PS3.

EW: Yeah, I don't own a PS3 either.

I only know one person who has one.

EW: A PS3? Yeah, we have a few people at work, but for the most part... although there are games coming out now that I'd like to play. I would like to play Drake's Fortune. So it's like if there are one or two more games that come out and I really want to play at home on the PS3, I think that's going to drive me over the edge.

KS: Ratchet & Clank, maybe.

EW: Yeah, I want to play Ratchet & Clank. I really love Ratchet & Clank games, but...

It's not necessarily worth buying a PS3 over.

EW: I just haven't finished... I've got a backlog of Ratchet & Clank games on the PS2 and the PSP, and there's a new PSP Ratchet & Clank coming out soonish, I think. I need to finish those before I buy a PS3 for it.

Narrative-wise?

EW: Dialogue-wise, any game Planet Moon has made, those guys are incredibly funny writers. They have a really good... they're the only team I know who brings the actors in all together in the studio, so they play off each other.

I think it helps a lot of their comedy. And Tim's games. I had a chance to see Brutal Legend about a month ago. They're working on that, and it's awesome. That's going to be great.

Concept art for Tim Schafer's upcoming Brutal Legend

They actually do that in Japan more. They bring all the voice actors in the same place. I think it's a really good idea, but obviously it's hard to schedule.

EW: It's hard to schedule, and I think there's some practical problems with it, too. I'd still like to try it someday.

You should. What do you think of the narrative in Call of Duty 4? I think in terms of myself, personally, in terms of the big-budget blockbuster-type game, I never felt like it was stupid or fake.

EW: No, Call of Duty 4, actually... I don't know why it wasn't nominated for best writing at the GDC. Yeah, Call of Duty 4 has set the bar on military-themed shooters, because I've never been interested in the story in a military-themed shooter. A lot of the Splinter Cell games, I can't button through the talky parts fast enough.

But Call of Duty 4 had arguably -- since Half-Life 1 -- it had the most awesome...the opening train ride scene was just great. And I don't want to spoil things, but all the twists in general... it was really great. And it didn't overstay its welcome, and even its gimmicky levels, like the...

The Ghillie Suit?

EW: The Ghillie Suit level is awesome. The one where you're doing the bombing run through the... I don't even know what they call that vision. Spy cam vision, or something? It's super-duper realistic, and in a way I had never really experienced before in a game. And it's a great game.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like