Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

25 years ago, NEC released the video game system that fell first in the 16-bit console wars -- but what an interesting failure it was. The history of the TurboGrafx-16 as told by those who were there.

The TurboGrafx-16.

If you mention the system to hardcore retro game fans, they'll know it -- but these days, 25 years on from its launch, it's barely even a footnote in the histories of the console wars. People still talk about the knock-down, drag-out battle between Nintendo and Sega. But NEC…

NEC made video games?

Now best known as a provider of network infrastructure, the Japanese giant was once a consumer electronics and personal computing force. While Sega and Nintendo battled for supremacy with the Genesis and the Super Nintendo, NEC provided a third option -- one that was smaller and sleeker and, in the West, almost totally ignored. By now, it's just about been forgotten.

Just about.

The TurboGrafx-16 went on sale in the U.S. in August of 1989. By the middle of 1994, it had been discontinued. I've spent weeks interviewing people who were there at the time, major players and minor, each of whom had a connection to the system.

They speak of a console that performed great in Japan. With a strong software lineup and an eye-catching design, it was assumed it would be a "slam dunk" in the West. But with a team that didn't understand the video game market, and major tactical mistakes, the TurboGrafx never even got off the ground. Its fans were passionate, but they were few in number, and Japanese management lost faith in the console, choking off support years before finally withdrawing it from sale.

This is the story of the TurboGrafx-16.

Just like in the United States, Nintendo was all-conquering in Japan's 8-bit era. As with the NES, hits like Super Mario Bros. meant that its Family Computer, or Famicom, reigned. But the system had been introduced to the Japanese market in 1983. Its technology was creaky. Even as it ascended to the heights of global popularity, some developers were beginning to worry.

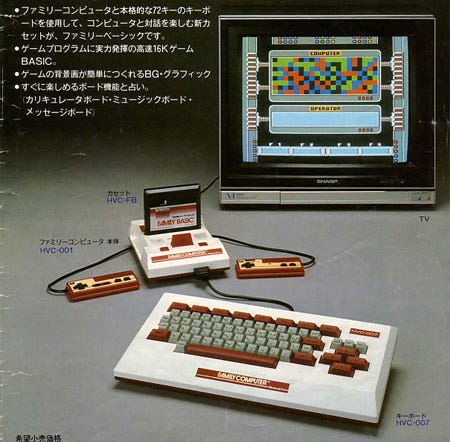

One company did more than worry about it. Hudson Soft, the first third party publisher for the Famicom and developer of the Family BASIC programming software and keyboard set that Nintendo released in Japan, turned its hand towards creating a new generation of NES.

Family BASIC

Family BASIC

"They were worried that the Family Computer was starting to go a little bit stale," says Rich O'Keefe, an engineer who worked at NEC in the U.S. on the TurboGrafx's development tools and developer relations.

Hudson was an unusual, experimental company that tried a lot of different things in the 1980s. Based in Sapporo, on Japan's northernmost island of Hokkaido, it was founded by the Kudo brothers, Yuji and Hiroshi.

Despite its early successes, Hudson wasn't as buttoned-down as many Japanese companies. "These guys are not the straightforward Japanese business types as you would think," says O'Keefe, a veteran of the 1980s Japanese game industry. He traveled to Japan to pow-wow with Hudson staff on technical issues prior to the TurboGrafx's U.S. release, after joining NEC. After he quickly showed that he understood the tech, one of the Hudson founders took him fishing -- in the December snow. "Hudson's a pretty unusual company," O'Keefe observes.

"They made a few mistakes, but basically they really did things that were always different, strange, weird, wonderful, wild. It was a real game company as opposed to a marketing company," says John Greiner, Hudson Soft's first American employee.

The Family BASIC relationship is "why they thought they could get away with designing Nintendo's next video game system," O'Keefe says. Problem was, Nintendo wasn't interested in Hudson's design, and the company wasn't large enough to manufacture a console on its own -- just engineer one.

Undaunted, Hudson approached Sega and other companies with its console. It finally found a buyer in 1980s home electronics giant NEC. The two had an existing relationship, because Hudson had built productivity software for the company's PCs.

"NEC said, 'Well, we're looking for a way to get in with kids, so we'll call this thing "heart of the computer," or the PC Engine,'" says John Brandstetter, who worked on the TurboGrafx in the U.S. "I think they got talked into this deal by Hudson Soft, and then it looked like a good market to them because they saw how much money Nintendo was making," O'Keefe says.

But the PC Engine's origins made it unusual in the marketplace: designed by Hudson and manufactured and marketed by NEC, it had two masters -- and distributed decision-making. Both companies supported it as first party software studios, though Hudson was more a force for original software, while NEC frequently released ports of games from other platforms.

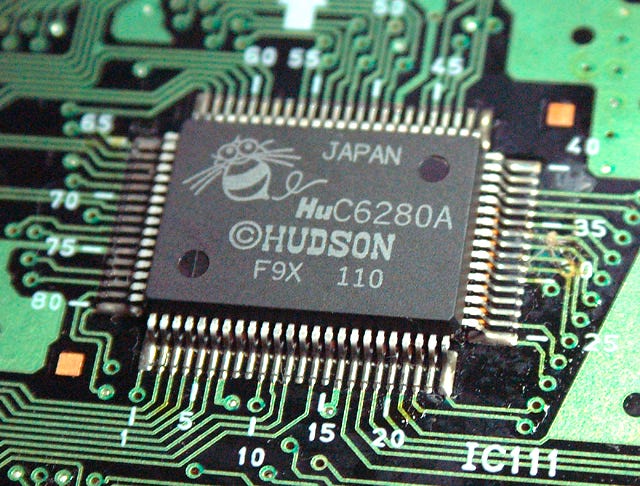

The Hudson-designed PC Engine CPU, a derivative of the NES' processor.

The Hudson-designed PC Engine CPU, a derivative of the NES' processor.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

The business relationship between the companies was unusual, too. Hudson got a royalty for every PC Engine manufactured, since it designed the CPU and GPU that powered the system; it also got a royalty on each and every game sold in the PC Engine's HuCARD cartridge format, which it also designed. The games were manufactured in Japan by Mitsubishi on behalf of Hudson, while NEC handled hardware production, and made its profits from selling systems.

A Hudson HuCARD, PC Engine's sleek cartridge format.

A Hudson HuCARD, PC Engine's sleek cartridge format.

The size of a credit card, It was retained for the TurboGrafx-16.

Photo credit: Bryan Ochalla

In October 1987, NEC launched the PC Engine in Japan. The system was an instant success; according to Steven Kent's book The Ultimate History of Video Games, the PC Engine outsold Nintendo's Famicom in 1988. Once the company was sure it had a hit on its hands, it decided to launch the system in the U.S. But it needed a team to do it.

It wasn't just NEC that needed to staff up to sell the PC Engine to Americans. In 1988, Hudson began to put together a team to help it market the PC Engine in the West.

In January of '88, Hudson co-founder Yuji Kudo hired John Greiner, an American who was traveling in Sapporo after college, to act as a liaison and product manager, and also recruited bilingual Japanese staff to handle other duties. The company needed English-speakers to interface with NEC, interpret for its staff, choose the games to send West, and localize them.

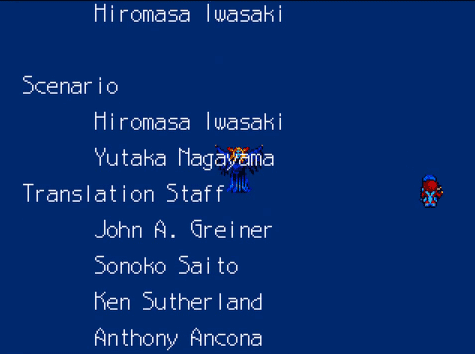

"They had no foreigners, they had very little English skill, so they needed somebody to help them," Greiner recalls. "Hudson created this international division because when NEC brought the system over to the United States, they needed expertise of Hudson Soft to market the software, and they needed to translate the text," says Sonoko Saito, who was hired to translate games and interpret for meetings between NEC and Hudson Soft.

The credits for the U.S. version of Ys Book I & II. In Japan, at Hudson Soft, Saito translated the text and Greiner polished it.

The credits for the U.S. version of Ys Book I & II. In Japan, at Hudson Soft, Saito translated the text and Greiner polished it.

NEC Japan had directed its U.S. branch to sell the PC Engine, so in Chicago, NEC Technologies boss Keith Schaefer put together a launch team. Schaefer, along with Ken Wirt and Bob Faber, had joined the company after having fled Atari's home computer division. "At the time we went to NEC, we didn't have any idea about doing video game stuff anymore," Wirt says.

Under Schaefer's direction, Wirt shifted gears from NEC's PC business to become the general manager of the TurboGrafx unit, with Faber working on the project too. As Wirt has it, "it just turned out they had these three guys who knew a lot about the video game business -- they were already working for them!"

The problem: The Atari team had worked in the company's home computer division, which mostly sold hardware; its game business was based on ports of arcade games that were already successful. The management team's expertise in the home console market was very limited. "They needed the software expertise. They were not software people," Greiner remembers.

I asked Carol Balkcom about NEC's strategy for the TurboGrafx. After conversing for awhile, I began to get the idea. I asked her, "The people at the company were not generally very well versed in the game business, in other words?"

"That's a very good way to put it," she replied.

The team did, however, have a bead on consumer marketing. Wirt and his team began to put together plans to launch the PC Engine in the U.S., and that included focus testing the system and its games with U.S. consumers. "The good news was we had a product that had already been introduced in Japan. So we were able to test that in the United States," he says.

Initial results were mixed, but promising: "People liked the gameplay, it was very fast, and it was the first system with 16-bit graphics," Wirt says. "But there was not a lot of enthusiasm for the name. People thought it was confusing."

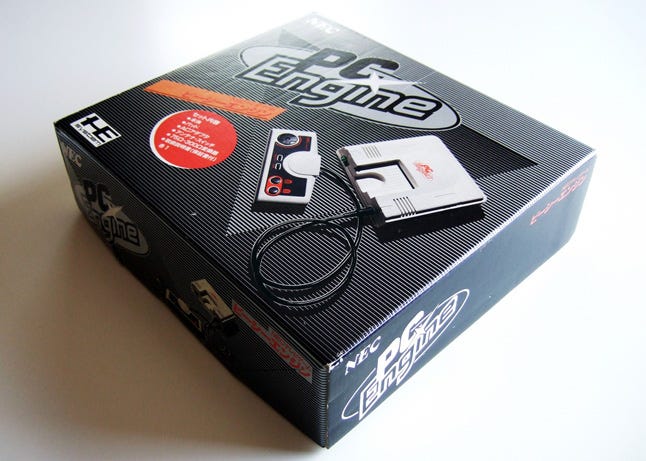

The PC Engine box. Take note of the control pad, and compare to the TurboGrafx-16 on the next page.

The PC Engine box. Take note of the control pad, and compare to the TurboGrafx-16 on the next page.

Photo credit: Bryan Ochalla

The company made the decision to redesign the PC Engine's casing for its introduction to the U.S. Compared to other consoles of the era, the PC Engine was tiny, thanks to its well-engineered internals and the credit card sized HuCARD format. However, "there was a feeling" that American consumers wanted something bigger -- and something more futuristic, Wirt says.

"We did a bunch of research around the name and we decided we had to change the name and the industrial design," Wirt says. The name was a simple change: "TurboGrafx" to refer to the system's speed and the strength of its visuals, which were clearer and much more colorful than earlier systems; "16" to refer to its 16-bit GPU, as "16-bit" was the keyword for that console generation. (Accessories became "Turbo" everything: TurboPad, TurboTap, TurboStick, and the HuCARD now the "TurboChip.")

"The marketing and advertising company came up with some sketches, and they conducted focus groups," says Carol Balkcom, who was part of NEC's launch team. Once the externals were designed, engineering began: "it takes time to do a redesign and a re-layout of stuff," says O'Keefe. "Plastic's not exactly a quick-turnaround item, especially if you're changing the design every so often."

The redesign of the hardware dragged on. O'Keefe says that the company wasted months trying to create a rubber-textured cover for the console's rear expansion port -- work which was abandoned when a usable solution could not be created. "It would have been nicer to have the same form factor as the Japanese. It would have cured a lot of problems, issues," O'Keefe says.

Hudson Soft wasn't thrilled with the look NEC selected, either. "They wanted to make it look like something you'd find on your stereo rack, where we prefered the small intimacy of the PC Engine," says Greiner. But NEC, he says, had its eyes on pushing its way into American living rooms, and wanted a different aesthetic. "They were marketing experts in The States, and they chose the look and the feel that they wanted."

Another former NEC staffer, who came on much later in the system's lifespan, has a different take: "Their idea was a dumb American stereotype: Bigger is better. That's all it is," says John Brandstetter, who joined NEC in 1991. O'Keefe (who worked for Atari in Japan prior to NEC) chalks the redesign up to "Atari mind-think," comparing it to the disastrous Atari 5200, which the company's marketers felt needed to be physically larger than its hit 2600 console to be successful (which it wasn't.)

"They wanted this to be big. They wanted to get into the living room, and this was a great opportunity to do so. They had already done so in Japan," says Greiner. The PC Engine's success made NEC complacent; the size of the opportunity masked its dangers.

The U.S. version of the PC Engine: The TurboGrafx-16.

The U.S. version of the PC Engine: The TurboGrafx-16.

Photo credit: Evan Amos

While NEC was handling the hardware side, Hudson worked on software. Having designed the console, the company produced a huge number of games for it, which it began to localize. In fact, Hudson titles dominated the system's lineup in the U.S., even more so than in Japan.

The PC Engine had plenty of Japanese support; with a U.S. launch imminent, it was time to get Western publishers and developers on board with the TurboGrafx-16. Hudson, naturally, created the development tools for the platform -- which were ported from NEC's Japan-only PC-98 format to the Western standard, MS-DOS, under O'Keefe's watch.

Hudson staff flew from Sapporo to Monterey, California, to throw a two-day developers conference that covered everything from the financials of producing games for the system to how to develop for the TurboGrafx-16, and its upcoming CD-ROM add-on, which had launched in Japan in 1988.

"We invited, I'd like to say, 25 to 30 of the top publishers at the time. And spent, I think it was about a two-day event. So we hosted them and just had a coming-of-mind of how we were going to roll the system out, what kind of games we were looking for, how we run the business," says Greiner. Hudson controlled game production, thanks to its deal with NEC.

At the conference, Hudson didn't generate much publisher interest in the TurboGrafx. But it did succeed in alienating Electronic Arts.

"Basically, there was a kind of weeding-out of developers who could actually participate in development of the first round of CD-ROM games," Greiner says. "We wanted the kind of emphatic push that we would get from somebody who really knew how to use that kind of space -- in other words, really great game developers."

In a meeting, Hudson staffers asked EA's team if it was up to the task of developing great CD-ROM games -- "we didn't think EA was that at the time, obviously, or otherwise we wouldn't have to ask them so deeply," says Greiner. "EA took offense to that -- they kind of walked out of the meeting and said, 'How dare you question us?'"

Neither Hudson nor NEC was able to convince third-party publishers to work with them in the West prior to launch. In Japan, it was a different story -- Namco was an early supporter of the system, and many smaller companies hopped from NEC's dominant PC-98 over to the console space. Yet NEC published their games in the West. "NEC decided to create a brand new business in the United States and do it all -- to distribute the hardware and the software," says Balkcom.

The delay in introducing the PC Engine to the U.S. wasn't just thanks to the hardware redesign or software localization. NEC was unsure about the viability of the PC Engine in the U.S., and began the expansion project late. "By the time I think they got into the game business, I think they were a little bit nervous, and I think they wanted to see how well they did in Japan," says O'Keefe.

If Japan had cold feet, it wasn't apparent at NEC in the U.S. The team had built up a head of steam with the project, and at that point, external reactions to the TurboGrafx-16 were promising, too: "the press reaction to it and the retailer reaction to it were very good. They thought we had good marketing, they thought the product was good, we had a big enough lineup of games," Wirt says.

Wirt told me that retailers were impressed by this commercial. Really.

Retailers were happy to have an alternative to Nintendo, which had a stranglehold on the video game market. Sega's 8-bit Master System had completely failed, and the company was an underdog rolling into the next generation; meanwhile, NEC had a reputation as a reliable consumer electronics company. "We got all the major retailers to carry the product," Wirt says.

If anything, NEC in Chicago was overconfident. "There was this hype they had built over the war that made everybody think this was going to be a slam dunk from the beginning," says Greiner. The PC Engine had been a proven success, and early signs for the TurboGrafx-16 were promising. NEC had big expectations.

Ironically, however, NEC Japan's caution about entering the U.S. market created only problems for the TurboGrafx-16. In truth, the delay in introducing the hardware in the West simply erased whatever advantage NEC had over its chief rival, Sega.

Sega's 16-bit system, the Mega Drive, launched in Japan in October 1988, a year after the PC Engine, but the U.S. version, called the Sega Genesis, arrived on shelves two weeks before the TurboGrafx-16, in August 1989 -- disastrous timing for NEC. Sega of America hadn't wasted time redesigning its console -- only minor cosmetic changes were made.

Keith Courage in Alpha Zones

Keith Courage in Alpha Zones

Sega's pack-in game was a conversion of proven arcade hit Altered Beast; NEC's pack-in was Keith Courage in Alpha Zones, a completely unknown Hudson home title. The hero, called Wataru in Japan, was renamed "Keith" in an attempt to butter up NEC boss Keith Schaefer.

"The pack-in should have been R-Type. If it was R-Type, it would have made a bigger splash," says Brandstetter. In fact, NEC could have had Irem's hit arcade shooter; Hudson's port was a launch title for the TurboGrafx-16. However, rather than catering to an arcade-playing core, NEC wanted a game that scored with both girls and boys in focus tests.

It made some sense -- but not to early adopters of expensive new consoles. The TurboGrafx-16 launched at $189. Adjusted for inflation to 2014 dollars, that's roughly $365.

Kato & Ken

Kato & Ken

The company's original choice had been a vaguely Super Mario-like platformer called Kato & Ken, but concerns over its scatological humor meant that it would miss the system's launch while Hudson re-developed the title.

After a lot of headaches, it was eventually bowdlerized and released as J.J. & Jeff well after launch. "We messed that game up by changing it so drastically," says Greiner. "I think they [parents] would have seen the humor in it. They worried about the wrong things, I think," says O'Keefe -- speaking not just about J.J & Jeff, but more generally about NEC's attitude.

"Worried," however, isn't the word to describe the mood at NEC in the U.S.

"The reality was, in terms of the graphics, the hardware, and the graphics that the hardware could produce, the TurboGrafx was superior to the Sega Genesis," Balkcom told me just weeks ago, reciting 25 year old talking points.

In truth, while the system's 16-bit GPU was speedy and offered excellent color depth, the TurboGrafx-16's main processor was 8-bit, and an evolution of the one in the NES. It was underpowered for the era.

Doug Snook, who worked at TurboGrafx-16 developer ICOM Simulations, talks of struggling with the TurboGrafx hardware: When developing Beyond Shadowgate, he says, "We ran into trouble with sprite drop-outs when the sword was extended, and more significantly we were forced by memory limitations to flip the character graphics horizontally for walking left and right."

Very soon after the console hit the market, however, it became apparent things were not going to plan: "the sales were kind of disappointing," says Wirt.

Though Nintendo steamrolled Sega in the 8-bit war, Sega's arcade success was tough to contend with in a fight based on graphics as much as gameplay. NEC was an upstart, and soon an underdog. The near-simultaneous launch -- "which we didn't know was going to happen till it got right pretty close," Wirt says -- was particularly damaging, given the circumstances.

But what really hurt the TurboGrafx-16, says Greiner, is the fact that NEC produced a huge number of consoles off the bat -- 750,000 units. (Brandstetter claims 735,000; Wirt called Greiner's estimate "probably a reasonable number." In 1991, Wirt told Computer Gaming World there were 750,000 TurboGrafx units in the U.S., but the article doesn't specify if these were simply produced, shipped to retail, or sold to consumers.)

"I think, as I said, the hype had a life of its own. And I think that it probably infected the thinking of management at NEC when they made that order: 'This is going to be big and we better be prepared. Let's make as much as the market needs so we're not caught short-handed,'" says Greiner.

Retailers, used to being starved by an arrogant Nintendo, asked for more hardware than they actually wanted. "That was their way. And we should have known that, right? That was our job to have known what that was going to do, and that we should have cut them back as well," Greiner says.

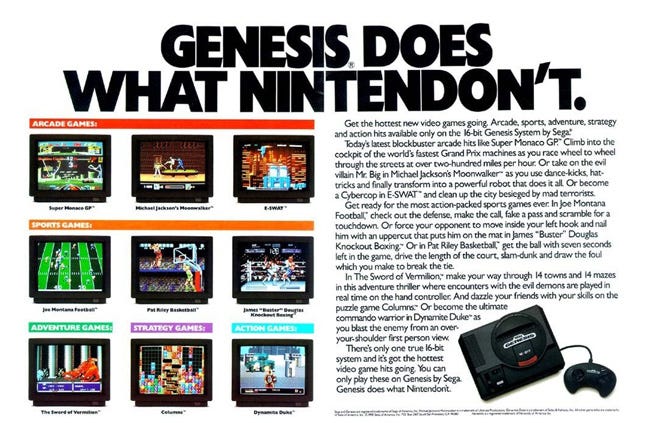

While both Sega and NEC started out with roughly the same amount of marketing money at launch -- $10 million for Sega, says this report; $10-15 million for NEC, according to the New York Times -- Sega's initial success meant that it soon felt comfortable investing more heavily in marketing. Its confrontational "Genesis does what Nintendon't" campaign is still remembered by all who were around at the time.

"It was really Sega that really had some great marketing that really trumped Nintendo at the time, if you remember. It was something that I think probably, more than anything else, is what got them into position to actually win," Greiner says.

Soon, Sega was trouncing NEC with marketing: "they outspent us probably 4-to-1 in marketing, or even higher -- I don't know, maybe 10-to-1," says Wirt. But NEC wasn't moving units, and had paid out an extraordinary amount of money to Hudson in royalties on its initial allotment of systems and games: "When they created 750,000 units, we were paid royalties on those 750,000 units. We were also paid royalties on each sale of each HuCARD. So Hudson did not hurt from the poor showing that they had against Sega," says Greiner.

NEC's Japanese management was hesitant to invest more money into the TurboGrafx-16 until it saw some return. It was also complacent. "To do some of the things we wanted to do, we needed support from Japan, from NEC corporate. And they didn't have a great understanding of why we were having problems, because they were doing quite well in Japan," says Wirt.

In Japan, Sega was never a force in the 16-bit war; the Mega Drive was a niche product. NEC had captured a lot of market share by launching the PC Engine early, and it had a better lineup of games for the market. Now, that situation was reversed in the U.S.

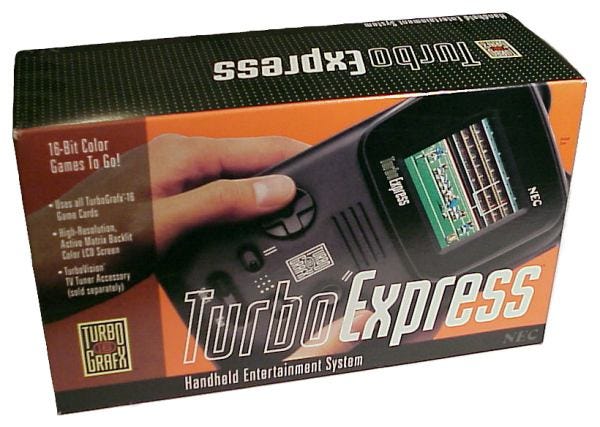

"They're all in Japan and they understand the Japanese market. They didn't see the problems we were having. They were kind of like, 'Give it more time, there's more titles coming, you're going to have these other products,'" says Wirt. NEC Japan expected the launch of the CD-ROM add-on and the TurboExpress handheld, which boasted a bright, color screen and used the same HuCARDs as the TurboGrafx, to make a splash.

However, it was quickly apparent that things were not going to plan: "let's say that after the first month, it was pretty clear," says Wirt. By Christmas 1989, says O'Keefe, it was obvious that "the sell-through just wasn't that good," and as soon as six months after the console shipped, it was "very apparent" how bad things were, Greiner says.

"I think they had some serious problems. ... I don't know what the market numbers were. Whatever they were, they were not good," says O'Keefe.

The problem wasn't just the software lineup, though it did contribute. Third parties were still making PC Engine games in Japan, but NEC couldn't attract publishers in the West. Only a few released games for the system. Those that did didn't tend to stick around.

"Basically, the economics were very difficult for publishers because the little HuCARDs -- they use a technology called chip-on-board," says Wirt. The minimum order was high and so was the cost of fabrication; the medium was "spectacular," says Wirt, thanks to the fact that it worked well for both portable and home games, but it just didn't work for publishers when taken in combination with the TurboGrafx's sluggish sales.

The economics were difficult for consumers, too. The system launched at the same price as the Sega Genesis, but its games were more expensive, broadly speaking. The most idiosyncratic thing about the PC Engine's design is the fact that it has only one controller port. Though it makes some sense given how small the system is, that feature was carried over to the much larger TurboGrafx. An adaptor was needed for two- to five-player play, adding unnecessary expense in the price-sensitive U.S. market.

And while NEC Japan thought the CD-ROM add-on would change the console's fortunes, NEC America began to get cold feet. "I think by that time, we were already pretty cautious because we knew it was going to be pretty expensive," says Wirt. Despite a fight to reduce its cost "below a normal kind of margin" for NEC, the add-on launched at $399 with no pack-in game.

16-bit rivals: The PC Engine HuCARD, as compared to Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo cartridges

16-bit rivals: The PC Engine HuCARD, as compared to Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo cartridges

NEC U.S. "knew it was expensive," says Wirt, so "we did not produce that many systems, and there wasn't that much software." In fact, evidence suggests the company shipped around 20,000 units of the TurboGrafx CD hardware in the U.S.

TurboGrafx CD launched at the end of 1989 with just two games available at retail: Fighting Street, a Hudson-developed port of Capcom's original Street Fighter, well before the series' explosive popularity, and Monster Lair, a solid but very obscure arcade shoot 'em-up. Neither was a showcase title.

A 1990 episode of Computer Chronicles, broadcast nationally on PBS. A segment on the TurboGrafx-CD begins at 17:26.

The CD-ROM unit does boost the system's capabilities drastically, and it was the first console to get such a unit by several years. But it had no reach in the U.S. "It was all new. TurboGrafx was new, the games were new, the notion of a CD-ROM was new, and because of that there was so much education of the market involved in order to make them choose TurboGrafx," says Balkcom.

"I mean, the hardware was decent enough, right? When we added the CD-ROM we should have been able to do a lot more with that. But, we didn't pursue it that much, because it just added too much cost to the game unit, I guess," O'Keefe says.

More CD-ROM titles didn't arrive until the back half of 1990, and the system's obscene cost didn't attract many takers. Even staunch PC Engine supporters that had U.S. presences ignored the TurboGrafx; NEC began to localize and publish CD games by Nihon Telenet -- despite the fact that the company had established a U.S. arm that same year and steadily released Sega Genesis games.

In fact, it was almost entirely up to NEC to support the TurboGrafx-16. With system sales failing to take off, companies were happy to let NEC take the risk. "In some cases they'd say, 'You know, we don't really want to publish ourselves. We'll license you our game. Why don't you publish it?' ... basically we were pretty much the only publisher as a result of that," Wirt says.

"The problem was, without a large installed base of the game systems, companies didn't want to take on the financial risk of development, publishing, and distribution. They were interested in licensing games to NEC to publish, only," says Balkcom. Sonoko Saito, who worked for Hudson Soft at the time, explains publishers' thinking: "It's much easier, and it's instant profits if they license the games to somebody else to publish, right?"

This created the perception in the West that only NEC supported the system, however. Magazines were full of ads for NES and Genesis games; NEC could only fill a few pages before things got too expensive. So NEC used advertising to try and kill two birds with one stone: "We tried to show the breadth of the games available, because that's one of the things that hurt us… we had a page spread that showed all the games coming out with the latest games highlighted," says Wirt.

There was another problem: the U.S. staff were not software people, as Greiner observed. They relied on NEC Japan to suggest games for the West, which O'Keefe said the company did with the best of intentions. Hudson also made its choices, and its titles continued to dominate the system's lineup. But NEC's U.S. staff were clueless about which games were good.

"As I recall, our decisions were informed in large part by the relationship between NEC Japan and the Japanese software companies," Balkcom said. The Atari crew's game expertise was pre-NES era, and it seems nobody at NEC knew much about contemporary arcade titles or player preferences at all.

"I think that the Americans [at NEC] underestimated the power of Sega in the market, because those arcade games were ported from success in Japan to success in the U.S.," Balkcom says.

Victor Ireland started out as a TurboGrafx fan and then a journalist. After developing a close relationship with NEC, he soon moved to become a TurboGrafx game publisher thanks to a mix of enthusiasm, frustration, and opportunity. His company, Working Designs, released its first two TurboGrafx-16 games in 1991.

"I became aware of so many cool games for PC Engine, and NEC was bringing over so many of the wrong games for the TurboGrafx," Ireland says. "The people in charge of picking what games to do were completely out of their element. A main producer was letting her little kids pick which games to bring over because she had no idea what she was looking at. It was absurd."

While Sega steadily released ports of its arcade hits and original console games, backed up by an increasing number of third parties, NEC struggled to select games for the West, and to get players interested in them: "we had a lot of education to do that Sega did not," Balkcom says.

Still, the system had some hits: Blazing Lazers, a 2D shooter developed by Hudson, was an early standout exclusive. Namco's macabre Splatterhouse courted controversy and looked very good doing it. Hudson Soft developed the first 5-player version of Bomberman for the PC Engine, and it "took on a life of its own" in the West, too, says Balkcom -- despite the expense of all those controllers.

Bonk's Adventure

Bonk's Adventure

And in 1990, the system's crowning glory, if ever it had one, arrived: Bonk's Adventure. This platformer, supplied by Hudson Soft, gave NEC a title to rally around and, arriving a year before Sonic the Hedgehog, was an early volley in the 16-bit mascot wars. Of any game for the TurboGrafx, it's the one people are most likely to have heard of. It gave the system an identity -- a face.

NEC didn't want to rely on Japanese games alone to sell the TurboGrafx-16. It contracted with ICOM Simulations, developers of the Shadowgate games, to create titles for both HuCARD and CD. It also hired Cinemaware, a darling of the 1980s PC scene, to convert its games to the TurboGrafx CD, as it was one of the only studios in the West that had cinematic ambitions for game development at the time.

NEC paid the two companies to convert their PC games -- such as Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective, and It Came from the Desert -- to the TurboGrafx CD. The problem was that the subject matter of the games was aimed at a PC audience that largely comprised adults. They were ignored by the console gamers of the time.

For his part, O'Keefe -- who oversaw developer support for NEC -- had trepidations about the U.S. developers that were selected, particularly in terms of their ability to use the CD-ROM system effectively: "I kept on trying to get them to start with something simpler so that they could get up to speed on the hardware to see if it was even doable. Because we had a lot of doubts on it. But they went ahead and did it anyway!"

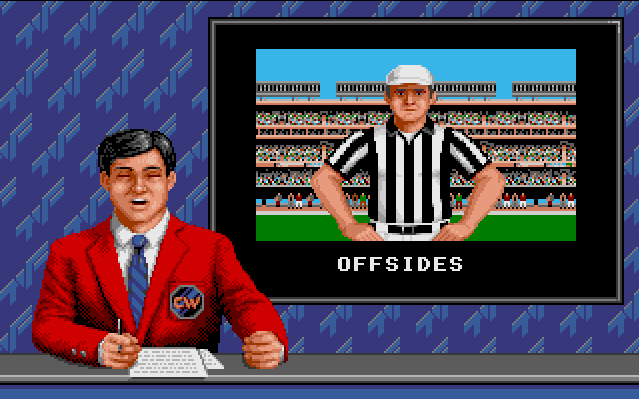

NEC continued to contract with Cinemaware and ICOM for ports and original titles; Cinemaware developed the system's TV Sports series of games -- which didn't have any player or league licenses. "NEC did not believe in licensing," Wirt says.

Cinemaware's TV Sports Football

Cinemaware's TV Sports Football

Faced with John Madden and Joe Montana's football games for the Genesis, sports fans didn't even have to a real choice to make. Says Wirt, "For $25,000 we could have licensed Pete Sampras and used him in a tennis game. And NEC said, 'No, we can't. We can't spend that $25,000 licensing Pete Sampras.'" Sampras went on to win the US Open in 1990 -- after NEC was forced to walk away from the deal.

The Cinemaware and ICOM deals were bad for NEC, but the team's lack of console expertise was to blame: "Six Japanese games would have done the TurboGrafx more good than two U.S. games, and the cost would have been about the same. It was just a completely losing strategy on NEC's part picking and marketing games," Ireland says. "NEC spent a lot of money from a development point, but some of the games are just not that interesting," says Brandstetter.

As 1990 wore on, there weren't many bright spots for NEC. Bonk's Adventure was an unqualified hit; and Hudson's port of Falcom's Ys Book I & II garnered major critical acclaim, including one 10 out of 10 score in EGM -- and it sold as well as a TurboGrafx CD-ROM game could be expected to, given the add-on's tiny install base.

NEC also introduced the TurboExpress in 1990 -- a handheld that both looked and acted like a Game Boy on steroids. It had a bright, beautiful color screen, and could play the same games as the TurboGrafx, thanks to the compactness of HuCARDS. Its drawbacks were significant, however: It cost $249, and gulped down AA batteries six at a time for just three hours of play. It was impressive technology, but not a hit. "That should have been a winner from day one. They just never marketed it right, I think," says O'Keefe.

NEC's warehouses were still bursting with TurboGrafx-16 systems, and with few unqualified hits, they weren't moving. Without marketing, without more hit games, and in the face of Sega's increasing success, they weren't going to. "There's not much you can do with a stockroom of hardware, but there's a lot you can do with marketing," says Greiner.

But NEC Japan wasn't interested in funding extensive new marketing efforts for the TurboGrafx-16, and nixed anything but business as usual. Balkcom says that the U.S. team, looking for a way to counter Sega's arcade advantage, even flirted with idea of creating a TurboGrafx-based arcade unit to showcase its games. It didn't happen.

"I think that by sometime in 1990, it was pretty clear that we weren't going to beat Sega. But we did think that we had an opportunity to be kind of a 'Porsche of video games.' It'd be more expensive, but better quality, and had the CD-ROM, the TurboExpress, and we could maybe live in a niche that would be a higher-end niche," says Wirt. O'Keefe agrees: "If they had just marketed it through Sharper Image or something like that -- decided to create a status symbol of it or something, market it in that way -- it might have hared a chance."

A clip from one of Ys Book I & II's CD-ROM powered cinema sequences, circa 1990.

A clip from one of Ys Book I & II's CD-ROM powered cinema sequences, circa 1990.

But by then, NEC wasn't interested in spending more money on the TurboGrafx. "There was a shining moment right around the time Bonk came out that it seemed like we might have an opportunity to occupy this higher-end niche, but then we just couldn't get the investment to make that happen. And as a result of that, I think by around the end of 1990, NEC was looking for a way out," Wirt says.

By then, Carol Balkcom had realized that things were unrecoverable. "It became fairly clear in the second year that we were not having the kind of success that NEC had hoped for," she says. "They thought that the business would be much larger than it was."

I asked O'Keefe if there was ever any post-launch optimism at NEC. His answer was simpler: "No." In fact, NEC was officially spooked, and for a good reason: "things that were going well in Japan started to go not-so-well in Japan," Wirt says.

The Japanese economy, which had been a miracle of the '80s, began to tank in 1990. Nintendo's Super Famicom was due at the end of that year, but "even before it came out, the PC Engine sales had started to go down in Japan because people were waiting," says Wirt.

NEC's resolve to compete began to waver. The company "was very enthusiastic about the games business in the beginning, because they'd done so well in Japan -- now, okay, weren't doing that well in in the U.S. and weren't doing that well in Japan," Wirt says.

A planned European launch turned into "too little, too late," says Wirt; you can still easily buy (borderline useless) new-in-box UK TurboGrafx units on eBay, even in 2014. No other European countries saw an official release of the system from NEC.

"We were a distant third and we tried very hard to make up that difference between Sega being the second and TurboGrafx being the third, and we just couldn't. We couldn't do it," Balkcom says.

It wasn't long before NEC wanted out of the U.S. console business.

The 750,000 unit buy-in is where Greiner puts most of the blame: "I think that put us in a position where we couldn't have the flexibility to stay on a marketing par with Sega or Nintendo at that time," he says. "That had the biggest effect of us losing the marketing battle." Too much money sunk into hardware left little money for promotion.

Balkcom says that the bosses' lack of game experience hurt things: "They came from electronics sales and marketing, but not from the game business… I think the company had enough resources. I just think we didn't know enough about the game business."

"They had VCR guys selling game systems and that stuff, and that's basically how the business was run. They never really took it seriously, and didn't push what they should have done, or get someone who really knew games in there in the get-go, and that's why a lot of things got chosen," Brandstetter says.

Says Balkcom: "You know, looking back, I'm sure we would all say, 'It was the games, stupid!'" The irony is that while the games were sitting there, in Japan, ready to be released, the people at NEC didn't know how to pick them: "if you know the PC Engine lineup, it makes no sense why the TurboGrafx failed," Brandstetter says.

"The biggest mistake, in my opinion, that we made, was that we did not have very many third party software companies. ... I don't know if it was NEC's idea or Hudson's idea, but we wanted to control both hardware and software," Saito says.

The TurboGrafx with CD-ROM add-on. Photo credit: Evan Amos

The TurboGrafx with CD-ROM add-on. Photo credit: Evan Amos

"If I'm looking at the TurboGrafx with the CD-ROM attachment and compare it versus the PC Engine with the CD-ROM attachment, which would you rather have?" - Rich O'Keefe

In a last-ditch effort at salvation -- and an ironic one, given the conversation Greiner had with Electronic Arts about developing for TurboGrafx -- NEC paid EA a pile of money for the John Madden license; Hudson Soft, in Japan, developed its own CD-ROM version of the game, released under the clunky title John Madden Duo CD Football.

"[A] stupid thing that we did is, we purchased the rights to sell the John Madden game from Electronic Arts, instead of asking them to publish from EA brand. Because if we had done that, they would market their games on their own, right? Then if we just buy the games and we sell it, then it's our responsibility to market the games and advertise it, and there are a lot of costs associated with that," says Saito.

"We paid a bunch of money for Madden, which was honestly stupid on our part, because EA didn't give a shit about us," Brandstetter says. "That was kind of a bad deal, but those were the kinds of deals that were made when NEC ran everything."

There aren't many warm feelings about NEC's management of the TurboGrafx to be had. "For me, the Keith Schaefer/Keith Courage thing is just a gift-wrapped package of the wrong-headed hubris that sank the TurboGrafx before it started. It's a perfect sign of everything that was wrong there from the very beginning," Ireland says.

"I would actually put it to the management of the American side of NEC at the time. And for the Japanese side to let them get away with it," O'Keefe says.

And NEC never did end up publishing that version of Madden -- though it did come out.

NEC soldiered on through 1991 with new game releases. From the outside, it looked like business as usual, even as Nintendo launched the Super Nintendo in the U.S. that August. But behind the scenes, the company began what Wirt calls "difficult negotiations" with Hudson Soft on an agreement to exit the U.S. console market.

The goal was to get away from the TurboGrafx without "disenfranchising the customers." Says Wirt, "NEC's a very honorable company," and its management didn't want to simply abandon the players who had invested in the TurboGrafx.

Wirt left NEC in the spring of 1991. "Negotiations started before I left, but it took a good long while after I left to reach a solution that was finally meaningful to both Hudson and NEC."

Unlike NEC, Hudson had profited from the TurboGrafx. "Well, the Hudson guys certainly made a ton of money off of the TurboGrafx. I don't know if anybody -- including NEC -- made as much money on the PC Engine or the TurboGrafx," O'Keefe says. As Greiner observed earlier, Hudson was paid a royalty on each console and HuCARD produced -- whether or not it sold.

The idea that took shape was to form a new company, ultimately called Turbo Technologies, to take over the business of selling the console and releasing games. Hudson would funnel its profits into running the U.S. TurboGrafx business.

"When it came time to extinguish the NEC brand, if you will, and Turbo Technologies took over, it was really a way to ease out of the relationship for NEC, and kind of have Hudson give back what they had made and try to guide the machine," Greiner says.

Turbo Technologies, Inc. -- or TTi, as it was widely known -- finally took over the TurboGrafx business in 1992. Headquartered in Los Angeles instead of the Chicago suburb that was home to NEC, it was run by Naoyuki Tsuji, a Hudson Soft staffer who moved from Japan to the U.S. to found the company.

Hudson had never been completely satisfied with how NEC was running the TurboGrafx business in the U.S. And though Hudson had a close relationship with NEC -- "Everyday, we were in contact with them. Every single day," says Greiner -- the company had mostly stayed hands-off, and acted in only an advisory role.

For example, when NEC decided to redesign the PC Engine's casing, says Greiner, "We definitely voiced our concern -- I remember that. But it wasn't our call." But dissatisfaction grew as the situation failed to improve.

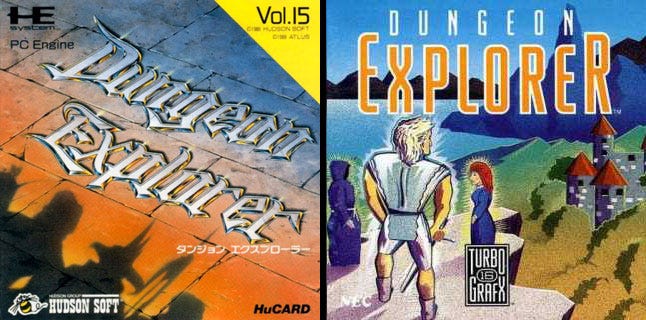

Left: The original Japanese cover for Dungeon Explorer. Right: NEC's U.S. artwork.

Left: The original Japanese cover for Dungeon Explorer. Right: NEC's U.S. artwork.

"I'm just remembering some of the artwork I saw on those TurboGrafx-designed covers. I'm laughing because that was probably some of the worst cover art I've ever seen in my life," Greiner said. For example: "Dungeon Explorer, which was actually a Hudson game, and we howled. We were laughing so hard at that, we were like, 'You've gotta be kidding.'"

When it came to packaging, says Balkcom, "We did not have the original materials. And I think our management believed that what we marketed in the United States needed to be different."

Hudson had lost faith in NEC, and NEC wanted out. A decision was reached. "We took a look at the large losses being recorded by the TurboGrafx operations based at NEC Chicago and decided that it was being handled by people who didn't understand the software business," Tsuji says.

Sonoko Saito was also asked to move to the U.S. for TTi by Hudson management: "they were saying it's because NEC is not doing well, and we need to get involved," she says.

John Brandstetter, who joined NEC in the final days of its involvement in the TurboGrafx business, moved over to TTi, where he was put in charge of picking the games for the U.S. market thanks to experience in the coin-op business and the fact that he was familiar with and understood the system's Japanese lineup.

"I was cleaning up a bunch of titles that were left over from NEC… So my job was just to try to survey them, see if they were worthwhile and continue them and finish them, or finish them if we had to -- contractually obligated to launch them on the console -- and then pick out the new lineup," Brandstetter says.

"I seem to recall the list of titles we were expected to make for NEC got pared down quite a bit when TTi took over," says Snook, who was producer of Beyond Shadowgate, ICOM's last game for the TurboGrafx, and one of its last releases.

TTi ended up publishing the TurboGrafx CD version of John Madden, as well as a number of other games left over from the NEC era, before canceling the rest of the development deals to focus on high-quality, already completed Japanese software.

The new company put together plans to launch the TurboDuo, an all-in-one unit that played both CD-ROM games and HuCARDs that NEC started selling in Japan in 1991. TTi took over distribution of the remaining TurboGrafx hardware and software stock, and began to release new games.

TTi direct-mailed this promo on VHS to registered TurboGrafx owners to build excitement for Lords of Thunder.

NEC's marketing was aimed at kids; TTi targeted older game enthusiasts, and touted the power of its CD-ROM games. A lot of the early advertising showcased a CD-ROM shooter, Lords of Thunder, with impressive graphics and sound. TTi even sent out a VHS video tape promoting the game to registered TurboGrafx owners. It was a relaunch that focused on the system's audiovisual strengths and the quality of its existing Japanese software library, with Hudson Soft in the driver's seat.

Since Hudson Soft already knew which games were popular in Japan, it didn't take long for the TTi crew to identify opportunities. Unlike with NEC, there wasn't much confusion. "We were starting to see which games were selling well, and then software is what drives the sales of the hardware, after all. So yeah, we felt focused on what games to bring to America," says Saito.

It wasn't long before they began to run into roadblocks, however.

Brandstetter used his background in the arcade business to set about signing deals to get coin-op hits onto the system. He brokered a deal for Mortal Kombat soon after it entered arcades, which was shot down by Japanese management.

"We had the rights to do it -- not signed, but I had the verbal agreement -- but then they didn't do it because Japan said, 'Oh, Mortal Kombat couldn't be done.' And then CES came up and we saw it on Game Gear and everything and I said, 'We could have done it! You guys didn't do it!'"

He also attempted to get the existing PC Engine version of Street Fighter II released in the West, but "NEC just wasn't willing to put up the money at that point. Because they weren't seeing revenue from the TurboGrafx on the American side," Brandstetter says.

Brandstetter also reached out to SNK, whose Neo-Geo fighting games were popular in arcades, to get them onto the TurboGrafx. "I brokered that deal, because Japan couldn't broker that deal," he says.

Tsuji brought Victor Ireland in on the SNK negotiations. "Tsuji asked me to help him get King of the Monsters 2 and World Heroes ported from SNK to TurboGrafx to bring some excitement to the system, and he funneled money to us to start that, but Japan found out and flew me to Japan to shut the project down personally," Ireland says.

The irony is that the deal went through -- on the Japanese side. The LA office had even came up with the idea of releasing a HuCARD that would add more system memory for running CD-ROM games -- enough for high-powered arcade ports. It was ultimately called the Arcade Card, and came out in Japan alongside PC Engine versions of SNK's games, some time after the TurboGrafx business was finally rolled up in the West.

SNK's World Heroes 2, from Hudson Soft, for the PC Engine with Arcade Card

SNK's World Heroes 2, from Hudson Soft, for the PC Engine with Arcade Card

But it was worse than that, Brandstetter says. TTi could rarely even get U.S. versions of existing Japanese games onto shelves. TTi would submit lists of games the company wanted to put out in the West, only to have Japan offer only a fraction: "if we gave a lineup, a list of what we thought would be the killer lineup for Christmas, we maybe got one out of the 10 or 15 titles we asked for," he says.

"And it wasn't like the titles had to be redone or anything. We would do the translation over here, the packaging had to be done. And then it just didn't happen," Brandstetter says. He flew to Japan for meetings, presenting research on what games would do well in the U.S. market -- only to wait, and wait, and then get very little.

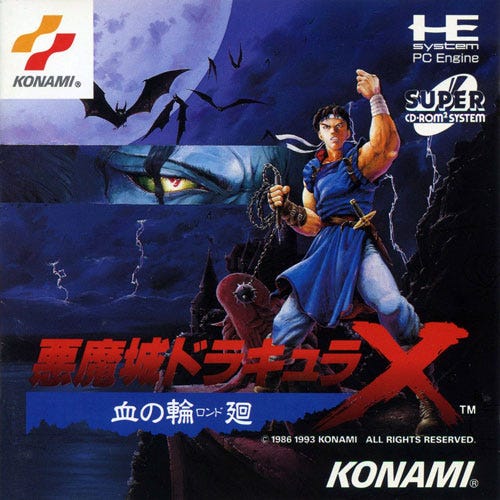

For example, he wanted to release Konami's PC Engine Castlevania title, Dracula X: Rondo of Blood -- predecessor to the classic Symphony of the Night. "Have you ever played that game? That would have made a huge difference. It sold like crazy over here in the gray market," he says. Nothing ever materialized out of his request. Every negotiation had to go through Japan, and answers were slow or not forthcoming at all.

"It's almost like you can sit there watching paint dry. It's like, you're telling them what will make money and they just don't. And it's proven. 'Look, here's Sega, they're doing things. Here's Nintendo, they're doing things. See what they're doing? If we just do what they're doing, we'll make money.' And that doesn't make sense to them," Brandstetter says.

TTi knew that the TurboGrafx had two major constituencies: fans of shooters, as Hudson had excelled at them -- "That was our big, big stuff," Brandstetter says -- and fans of RPGs, built by Ys and bolstered by the efforts of Victor Ireland's Working Designs.

"That was our key audience, that was kind of what made us," says Brandstetter. Cosmic Fantasy 2, a Telenet-developed CD-ROM RPG that Ireland released in 1992, sold "almost 1:1" with the TurboGrafx CD-ROM hardware NEC had released to the market prior to the introduction of the Duo, Ireland says (which is where the 20,000 unit install base figure comes from.) There was even talk of packing it in with the TurboDuo (the system included the first two Bonk games, Hudson shooter Gate of Thunder, and RPG hit Ys Book I & II.)

Konami's Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, one of the most critically acclaimed titles of the 16-bit era.

Konami's Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, one of the most critically acclaimed titles of the 16-bit era.

The system had "so many great games in my favorite genres -- RPG, shooters, and arcade/action," says Ireland. But despite his efforts, and those of the TTi crew, too few saw the light of day in the U.S.

"I was in Japan all the time, in meetings with these guys, saying, 'Here's the lineup. Here's why.' 'Well, you need to research.' 'Okay. Well, here it is again. Here's why.' And then, nothing. You'd hear nothing back for months," says Brandstetter.

Brandstetter showed so much enthusiasm that Hudson executives had the idea of turning him into a mascot for the system -- like they had in Japan with Toshiyuki Takahashi, a marketing staffer that the company christened "Takahashi-meijin," or "Master Takahashi," and used in advertisements and sent on promotional tours to gin up interest in Hudson's games. Kids looked up to Takahashi.

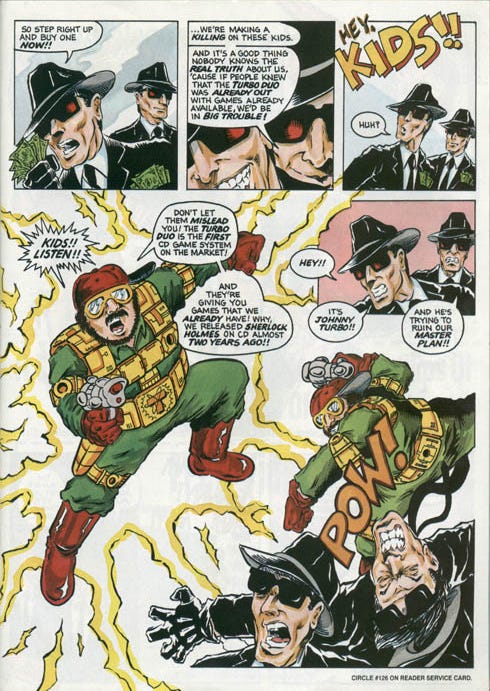

"The idea came from Japan, when I was there: 'John and Takahashi! John should be the American Takahashi-meijin!'" The result was a widely derided series of comic book-style advertisements casting Brandstetter as "Johnny Turbo," in a fight against "Feka" -- a cheesy analogue for Sega.

As a marketing concept, it was a bomb, particularly in the face of the sophisticated marketing blitz from Sega and Nintendo, who were in full-on console war mode.

Despite the unhelpfulness of Japanese management, initial results with the TurboDuo were promising, and Tsuji asked for a major marketing budget to take on Sega and Nintendo for real.

Needless to say, that didn't happen.

"Marketing is, over here [in Japan], it's not the same kind of animal, so it was very hard for them to understand that part," says Greiner. The Japanese, cautious about the U.S. market to begin with, also didn't understand it: "We had all these great games; we really knew how to create superior products. We just never knew how to market them in the West."

When TTi was founded, says Brandstetter, "We thought we had the freedom, but we still had the boat anchor of Japan. So, if we had had our own money to spend and not have to go to Japan for everything, we would have probably done fine."

Ireland backs that up: "Tsuji-san really wanted to make it work, but it was pretty clear within the first six to eight months that Japan wanted it to fail and just shut it down."

Greiner confirms that, from Hudson's perspective, that isn't far from the truth: Japan always saw the system as in "a bit of a downward spiral," he says. "So I'm not sure how much hope there was to actually revive it into a winner. It was more to kind of gradually extinguish the cause, if you will."

The effect on TTi was obvious: "So we're kind of like a bathtub toy just spinning around in circles with no direction that we could take, because the money wasn't there," Brandstetter says. Things were complicated by the fact that the U.S. slid into a recession in the early 1990s: "The yen went crazy and the dollar tanked. That, I think, hurt us a lot."

From 1992 into 1993, TTi kept releasing games, but "With no lineup, no marketing, no money for merchandising. We were done," says Brandstetter. During 1993, TTi had submitted another list of titles to Japan with hopes of releasing them that fall, and things looked good. Brandstetter began talking them up to video game magazine editors -- only to be told by Japanese management, "Oh, no. We're not getting any of that."

"And that was kinda like, the beginning of the end, there," he says. Christmas 1993 passed, and by then, stores had stopped carrying TTi's releases. Its last several games were shipped via mail-order only, and in meetings between TTi staff and Japanese management at the 1994 summer CES show in Las Vegas, the decision was made to formally pull the plug on TTi and the TurboGrafx.

"We did get some attention from the people in the industry and the people who liked the games, but as I said, it only lasted for a certain time and then declined," Saito says. Though the desire to relaunch the system "was not faked" by the people at TTi, says Greiner, there was no will in Japan to make a strong showing of it.

"The people I worked with at TTi were no less dedicated than Sega, but they were just beaten down by too much meddling from Japan and way too little money to make a real difference in the U.S. market," says Ireland. Snook, the Beyond Shadowgate developer, says that Brandstetter and Saito "were both great people to work with."

All remaining stock was passed to a new company started by TTi called Turbo Zone Direct, which continued to service TurboGrafx systems and sell games and accessories via mail order and online until 2001, under contract from NEC.

By the time TTi exited the market, the TurboGrafx had only 138 game releases, and had only ever had five third party licensees. In contrast, the PC Engine had well over 600 games, and was broadly supported until 1995, with its last game coming out in 1999.

Though it introduced the TurboDuo, TTi had never had to manufacture more TurboGrafx-16 units; in fact, says Brandstetter, the last 100,000 to 200,000 U.S. consoles were unloaded on the Brazilian market, with their expansion ports disabled. The initial order NEC made in 1989 for 750,000 units never sold through to U.S. customers. As for the Duo? "Turbo Zone Direct had Duos for at least 10 years," Brandstetter says.

Hudson Soft kept the PC Engine and TurboGrafx alive on the Wii's Virtual Console and the PlayStation Network, but there's been no activity since 2011. The company was acquired by Konami in 2012. The console generation has changed, now, and even those games will eventually fade. Without Hudson Soft boosting its erstwhile creation, it's unlikely that future devices will support the system's library.

When I asked Greiner what he thinks will happen, he wasn't optimistic. He'd looked into the issue himself. "I think it's the end. I think unless somebody's going to bring something back that they want to remake, then there won't be anything, no. It's definitely it."

Many of the people who worked on the system did love it. "If there was any old machine I'd want to play, it would definitely be TurboGrafx, absolutely. No doubt about it," says Greiner. "It was revolutionary at the time, and so many fun games."

The ill-fated TurboExpress -- the handheld that played TurboGrafx games -- is a particular favorite of the people I spoke to. "I thought it was a very, very cool handheld system. Nobody else had something like that back then. It's a shame that it didn't sell well at all," says Saito. "I still have my TurboGrafx Express. I pull it out every once in a while to remind me that I'm not in the game business anymore," O'Keefe laughed.

But it's no surprise that the people I spoke to didn't have very fond memories of working on the TurboGrafx-16 -- "it was a somewhat painful experience for me," says Ken Wirt.

Brandstetter's frustration is still palpable, 20 years after he quit the company. "It's like you got handed the winning lottery ticket with the numbers scratched off and it's worth a million bucks, but somehow on the way to the post office on the way to turn it in, you peed on it or threw it away. That's basically what happened to the Turbo, or the PC Engine, here."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like